The Endocrine System

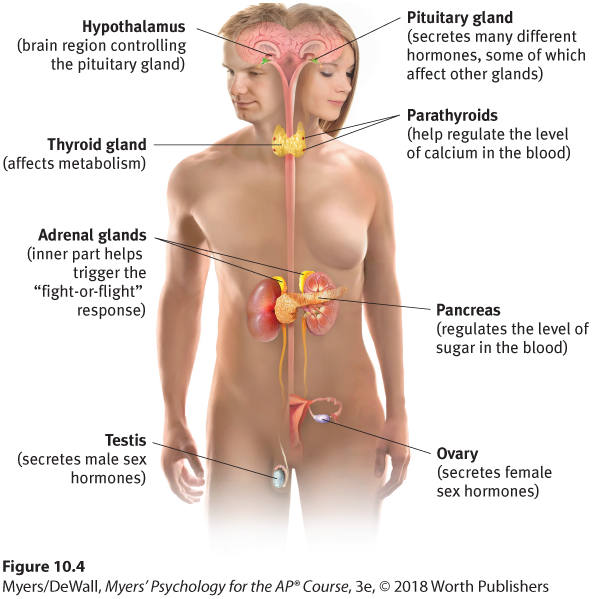

So far we have focused on the body’s speedy electrochemical information system. Interconnected with your nervous system is a second communication system, the endocrine system (Figure 10.4). The endocrine system’s glands secrete another form of chemical messengers, hormones, which travel through the bloodstream and affect other tissues, including the brain. When hormones act on the brain, they influence our interest in sex, food, and aggression.

Figure 10.4 The endocrine system

Some hormones are chemically identical to neurotransmitters (the chemical messengers that diffuse across a synapse and excite or inhibit an adjacent neuron). The endocrine system and nervous system are therefore close relatives: Both produce molecules that act on receptors elsewhere. Like many relatives, they also differ. The speedier nervous system zips messages from eyes to brain to hand in a fraction of a second. Endocrine messages trudge along in the bloodstream, taking several seconds or more to travel from the gland to the target tissue. If the nervous system transmits information with text-message speed, the endocrine system delivers an old-fashioned letter.

But slow and steady sometimes wins the race. Endocrine messages tend to outlast the effects of neural messages. Have you ever felt angry long after the cause of your angry feelings was resolved (say, your friend apologized for her rudeness)? You may have experienced an “endocrine hangover” from lingering emotion-related hormones. The persistence of emotions—even without conscious awareness of what caused them—was dramatically evident in one ingenious experiment. Brain-damaged patients unable to form new conscious memories watched a sad film and later a happy film. After each viewing, they did not consciously recall the films, but the sad or happy emotion persisted (Feinstein et al., 2010).

In a moment of danger, the ANS orders the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys to release epinephrine and norepinephrine (also called adrenaline and noradrenaline). These hormones increase heart rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar, providing a surge of energy known as the fight-or-flight response. When the emergency passes, the hormones—and the feelings—linger a while.

The most influential endocrine gland is the pituitary gland, a pea-sized structure located in the core of the brain, where it is controlled by an adjacent brain area, the hypothalamus (more on that shortly). Among the hormones released by the pituitary is a growth hormone that stimulates physical development. Another is oxytocin, which enables contractions associated with birthing, milk flow during nursing, and orgasm. Oxytocin also promotes pair bonding, group cohesion, and social trust (De Dreu et al., 2010; Zak, 2012). During a laboratory game, those given a nasal squirt of oxytocin rather than a placebo were more likely to trust strangers with their money and with confidential information (Kosfeld et al., 2005; Marsh et al., 2015; Mikolajczak et al., 2010).

Pituitary secretions also direct other endocrine glands to release their hormones. The pituitary, then, is a master gland (whose own master is the hypothalamus). For example, under the brain’s influence, the pituitary triggers your sex glands to release sex hormones. These in turn influence your brain and behavior (Goetz et al., 2014). So, too, with stress. A stressful event triggers your hypothalamus to instruct your pituitary to release a hormone that causes your adrenal glands to flood your body with cortisol, a stress hormone that increases blood sugar.

This feedback system (brain → pituitary → other glands → hormones → body and brain) reveals the intimate connection of the nervous and endocrine systems. The nervous system directs endocrine secretions, which then affect the nervous system. Conducting and coordinating this whole electrochemical orchestra is that flexible maestro we call the brain.