Structure of the Cortex

If you opened a human skull, exposing the brain, you would see a wrinkled organ, shaped somewhat like the meat of an oversized walnut. Without these wrinkles, a flattened cerebral cortex would require triple the area—roughly that of a large pizza. The brain’s left and right hemispheres are filled mainly with axons connecting the cortex to the brain’s other regions. The cerebral cortex—that thin surface layer—contains some 20 to 23 billion of the brain’s nerve cells and 300 trillion synaptic connections (de Courten-Myers, 2005). Being human takes a lot of nerve.

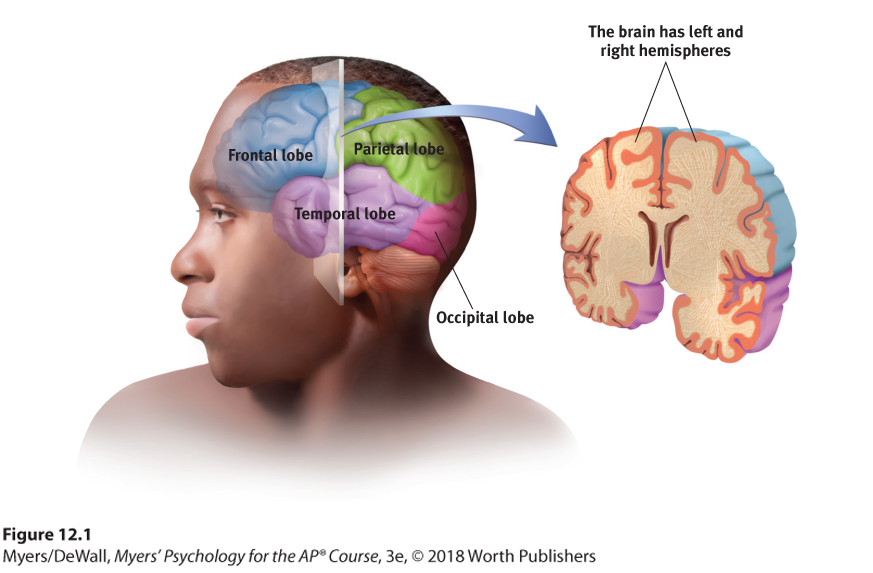

Each hemisphere’s cortex is subdivided into four lobes, separated by prominent fissures, or folds. Starting at the front of your brain and moving over the top, there are the frontal lobes (behind your forehead), the parietal lobes (at the top and to the rear), and the occipital lobes (at the back of your head). Reversing direction and moving forward, just above your ears, you find the temporal lobes. Each of the four lobes carries out many functions, and many functions require the interplay of several lobes (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 The cortex and its basic subdivisions

Flip It Video: Structure and Function of the Cortex

Flip It Video: Structure and Function of the Cortex