How Do We Learn?

By learning, we humans adapt to our environments. We learn to expect and prepare for significant events such as food or pain (classical conditioning). We learn to repeat acts that bring rewards and avoid acts that bring unwanted results (operant conditioning). We learn new behaviors by observing events and people, and through language, we learn things we have neither experienced nor observed (cognitive learning). But how do we learn?

More than 200 years ago, philosophers John Locke and David Hume echoed Aristotle’s conclusion from 2000 years earlier: We learn, first, by association. Our minds naturally connect events that occur in sequence. Suppose you see and smell freshly baked bread, eat some, and find it satisfying. The next time you see and smell fresh bread, you will expect that eating it will again be satisfying. So, too, with sounds. If you associate a sound with a frightening consequence, hearing the sound alone may trigger your fear. As one 4-year-old exclaimed after watching a TV character get mugged, “If I had heard that music, I wouldn’t have gone around the corner!” (Wells, 1981).

Learned associations often operate subtly:

- Give people a red pen (associated with error marking) rather than a black pen and, when correcting essays, they will spot more errors and give lower grades (Rutchick et al., 2010).

- When voting, people are more likely to support taxes to aid education if their assigned voting place is in a school (Berger et al., 2008).

Learned associations also feed our habitual behaviors (Wood et al., 2014). Habits can form when we repeat behaviors in a given context—sleeping in a certain posture in bed, biting our nails in class, eating popcorn in a movie theater. As behavior becomes linked with the context, our next experience of that context will evoke our habitual response. Especially when we’re mentally fatigued, we tend to fall back on our habits (Neal et al., 2013). That’s true of both good habits (eating fruit) and bad (overindulging in candy) (Graybiel & Smith, 2014). To increase our self-control, and to connect our resolutions with positive outcomes, the key is forming “beneficial habits” (Galla & Duckworth, 2015).

How long does it take to form a beneficial habit? To find out, one British research team asked 96 university students to choose some healthy behavior (such as running before dinner or eating fruit with lunch), to do it daily for 84 days, and to record whether the behavior felt automatic (something they did without thinking and would find it hard not to do). On average, behaviors became habitual after about 66 days (Lally et al., 2010). Is there something you’d like to make a routine or essential part of your life? Just do it every day for two months, or a bit longer for exercise, and you likely will find yourself with a new habit. This happened for both of us—with a midday workout [DM] or late afternoon run [ND] having long ago become an automatic daily routine.

Other animals also learn by association. Disturbed by a squirt of water, the sea slug Aplysia protectively withdraws its gill. If the squirts continue, as happens naturally in choppy water, the withdrawal response diminishes. We say the slug habituates. (Habituation is what happens when repeated stimulation produces waning responsiveness.) But if the sea slug repeatedly receives an electric shock just after being squirted, its protective response to the squirt instead grows stronger. The animal has associated the squirt with the impending shock.

Complex animals can learn to associate their own behavior with its outcomes. An aquarium seal will repeat behaviors, such as slapping and barking, that prompt people to toss it a herring.

By linking two events that occur close together, both sea slugs and seals are exhibiting associative learning. The sea slug associates the squirt with an impending shock; the seal associates slapping and barking with a herring treat. Each animal has learned something important to its survival: anticipating the immediate future.

This process of learning associations is conditioning. It takes two main forms:

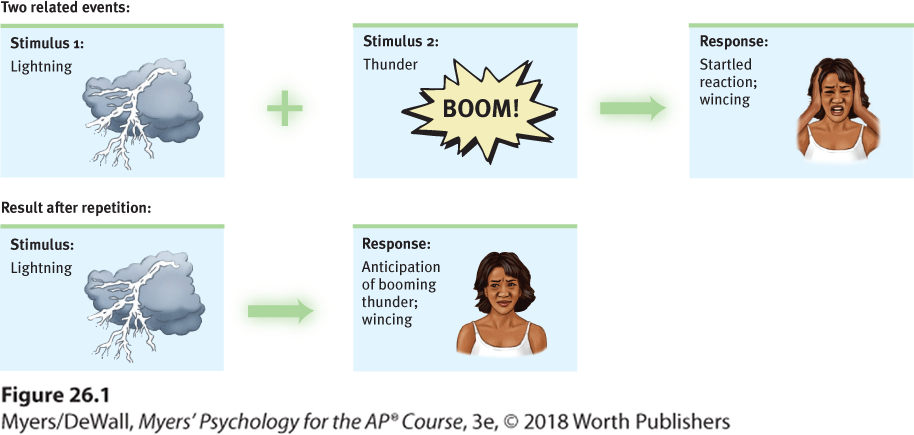

- In classical conditioning, we learn to associate two stimuli and thus to anticipate events. (A stimulus is any event or situation that evokes a response.) We learn that a flash of lightning signals an impending crack of thunder; when lightning flashes nearby, we start to brace ourselves (Figure 26.1). We associate stimuli that we do not control, and we respond automatically (exhibiting respondent behavior).

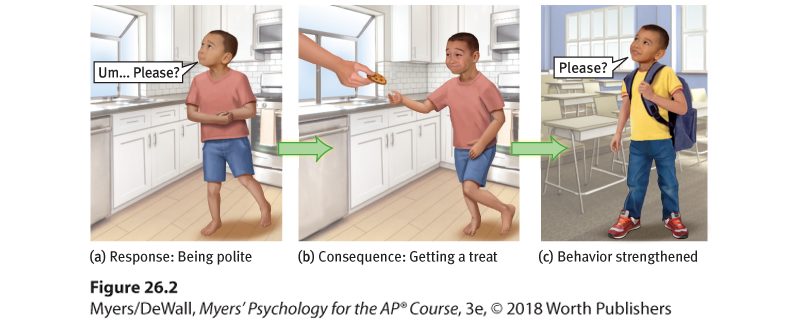

- In operant conditioning, we learn to associate a response (our behavior) and its consequence. Thus we (and other animals) learn to repeat acts followed by good results (Figure 26.2) and avoid acts followed by bad results. These associations produce operant behaviors (which operate on the environment to produce a consequence).

Figure 26.1 Classical conditioning

Figure 26.2 Operant conditioning

To simplify, we will explore these two types of associative learning separately. Often, though, they occur together. Consider the Japanese cattle ranch where the clever rancher outfitted his herd with electronic pagers which he called from his cell phone. After a week of training, the animals learned to associate two stimuli—the beep of their pager and the arrival of food (classical conditioning). But they also learned to associate their hustling to the food trough with the pleasure of eating (operant conditioning), which simplified the rancher’s work. Classical conditioning + operant conditioning did the trick.

Conditioning is not the only form of learning. Through cognitive learning, we acquire mental information that guides our behavior. Observational learning, one form of cognitive learning, lets us learn from others’ experiences. Chimpanzees, for example, sometimes learn behaviors merely by watching others perform them. If one animal sees another solve a puzzle and gain a food reward, the observer may perform the trick more quickly. So, too, in humans: We look and we learn.

“ Watch your thoughts, they become words;

watch your words, they become actions;

watch your actions, they become habits;

watch your habits, they become character;

watch your character, for it becomes your destiny.”

Attributed to nineteenth-century fugitive cowboy Frank Outlaw, 1977

Let’s look more closely now at classical conditioning.