Learning and Personal Control

Problems are unavoidable. This fact gives us a clear message: We need to learn to cope with the problems in our lives, alleviating the stress they cause with emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods. We address some problems, called stressors, directly, with problem-focused coping. If our impatience leads to a family fight, we may go directly to that family member to work things out. We tend to use problem-focused strategies when we feel a sense of control over a situation and think we can change the circumstances, or at least change ourselves to deal with the circumstances more capably. We turn to emotion-focused coping when we believe we cannot change a situation. If, despite our best efforts, we cannot get along with that family member, we may relieve stress by reaching out to friends for support and comfort. This can be adaptive, but sometimes our emotion-focused coping can harm our health, such as when we respond by eating comforting but fattening foods. When challenged, some of us tend to respond with cool problem-focused coping, others with emotion-focused coping (Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007). Our feelings of personal control, our explanatory style, and our supportive connections all influence our ability to cope successfully.

Emotion-focused coping Reaching out to friends can help us attend to our emotional needs in stressful situations.

Perceived Loss of Control

Learning also influences our sense of empowerment versus helplessness. Picture the scene: Two rats receive simultaneous shocks. One can turn a wheel to stop the shocks. The helpless rat, but not the wheel turner, becomes more susceptible to ulcers and lowered immunity to disease (Laudenslager & Reite, 1984). In humans, too, uncontrollable threats trigger the strongest stress responses (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004).

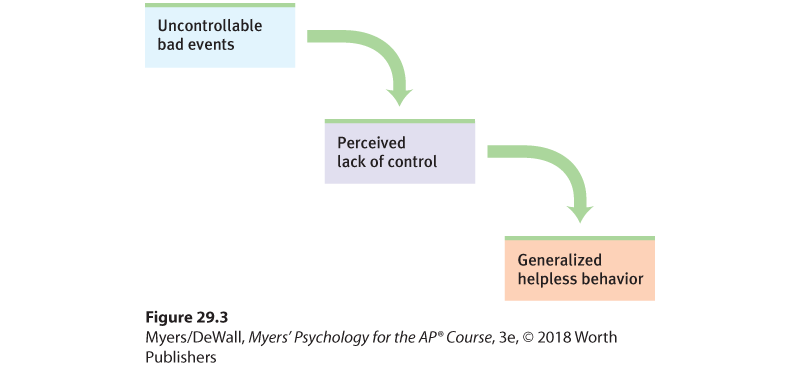

Any of us may feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed after experiencing a series of bad events beyond our personal control. Martin Seligman and his colleagues have shown that for some animals and people, a series of uncontrollable events creates a state of learned helplessness, with feelings of passive resignation (Figure 29.3). In experiments, dogs were strapped in a harness and given repeated shocks, with no opportunity to avoid them (Seligman & Maier, 1967). Later, when placed in another situation where they could escape the punishment by simply leaping a hurdle, the dogs displayed learned helplessness; they cowered as if without hope. Other dogs that had been able to escape the first shocks reacted differently. They had learned they were in control and easily escaped the shocks in the new situation (Seligman & Maier, 1967). People have shown similar patterns of learned helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978, 1989; Seligman, 1975).

Figure 29.3 Learned helplessness

When animals and people experience no control over repeated bad events, they often learn helplessness.

Perceiving a loss of control, we become more vulnerable to stress and ill health. A famous study of elderly nursing home residents with little perceived control over their activities found that they declined faster and died sooner than those given more control (Rodin, 1986). Workers able to adjust office furnishings and control interruptions and distractions in their work environment have also experienced less stress (O’Neill, 1993). Such findings help explain why British executives have tended to outlive those in clerical or laboring positions, and why Finnish workers with low job stress have been less than half as likely to die of stroke or heart disease as those with a demanding job and little control. The more control workers have, the longer they live (Bosma et al., 1997, 1998; Kivimaki et al., 2002; Marmot et al., 1997).

Control also helps explain a link between economic status and longevity (Jokela et al., 2009). In one study of 843 grave markers in an old cemetery in Glasgow, Scotland, those with the costliest, highest pillars (indicating the most affluence) tended to have lived the longest (Carroll et al., 1994). Likewise, American presidents, who are generally wealthy and well-educated, have had above-average life spans (Olshansky, 2011). Across cultures, high economic status predicts a lower risk of heart and respiratory diseases (Sapolsky, 2005). Wealthy parents also tend to have wealthy, healthy children (Savelieva et al., 2016). With higher economic status come reduced risks of low birth weight, infant mortality, smoking, and violence. Even among other primates, those at the bottom of the social pecking order have been more likely than their higher-status companions to become sick when exposed to a cold-like virus (Cohen et al., 1997).

Why does perceived loss of control predict health problems? Because losing control provokes an outpouring of stress hormones. When rats cannot control shock or when humans or other primates feel unable to control their environment, stress hormone levels rise, blood pressure increases, and immune responses drop (Rodin, 1986; Sapolsky, 2005). Captive animals experience more stress and are more vulnerable to disease than their wild counterparts (Roberts, 1988). Human studies confirm that stress increases when we lack control. The greater nurses’ workload, the higher their cortisol level and blood pressure—but only among nurses who reported little control over their environment (Fox et al., 1993). The crowding in high-density neighborhoods, prisons, and college and university dorms is another source of diminished feelings of control—and of elevated levels of stress hormones and blood pressure (Fleming et al., 1987; Ostfeld et al., 1987).

Increasing control—allowing prisoners to move chairs and to control room lights and the TV; having workers participate in decision making; allowing people to personalize their workspace—has noticeably improved health and morale (Humphrey et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2012; Ruback et al., 1986). In the case of nursing home residents, 93 percent of those who were encouraged to exert more control became more alert, active, and happy (Rodin, 1986). As researcher Ellen Langer concluded, “Perceived control is basic to human functioning” (1983, p. 291). “For the young and old alike,” she suggested, environments should enhance people’s sense of control over their world. No wonder mobile devices and online streaming, which enhance our control of the content and timing of our entertainment, are so popular. When a massive earthquake hit the Chinese city of Ya’an in 2013, victims took control of the situation by using their mobile devices. Those who sent frequent text messages and used mood-improving apps suffered the least stress (Jia et al., 2016).

Google has incorporated these principles effectively. Each week, Google employees can spend 20 percent of their working time on projects they find personally interesting. This Innovation Time Off program has increased employees’ personal control over their work environment, and it has paid off: Gmail was developed this way.

People thrive when they live in conditions of personal freedom and empowerment. At the national level, citizens of stable democracies report higher levels of happiness (Inglehart et al., 2008). Freedom and personal control foster human flourishing. But does ever-increasing choice breed ever-happier lives? Some researchers suggest that today’s Western cultures offer an “excess of freedom”—too many choices. The result can be decreased life satisfaction, increased depression, or even behavior paralysis (Schwartz, 2000, 2004). In one study, people offered a choice of one of 30 brands of jam or chocolate were less satisfied with their decision than were others who had chosen from only 6 options (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). This tyranny of choice brings information overload and a greater likelihood that we will feel regret over some of the things we left behind. (Do you, too, ever waste time agonizing over too many choices?)

Happy to have control Working alongside Habitat for Humanity volunteers, this family helped build their own new home.

Internal Versus External Locus of Control

If experiencing a loss of control can be stressful and unhealthy, do people who generally perceive they have control of their lives enjoy better health? Consider your own perceptions of control. Do you believe that your life is beyond your control? That getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time? Or do you more strongly believe that you control your own fate? That being a success is a matter of hard work?

Hundreds of studies have compared people who differ in their perceptions of control. On the one side are those who have what psychologist Julian Rotter called an external locus of control, the perception that chance or outside forces control their fate. In one study of more than 1200 Israeli individuals exposed to missile attacks, those with an external locus of control experienced the most posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (Hoffman et al., 2016). On the other side are those who perceive an internal locus of control, who believe they control their own destiny. In study after study, the “internals” have achieved more in school and work, acted more independently, enjoyed better health, and felt less depressed than did the “externals” (Lefcourt, 1982; Ng et al., 2006). In longitudinal research on more than 7500 people, those who had expressed a more internal locus of control at age 10 exhibited less obesity, lower blood pressure, and less distress at age 30 (Gale et al., 2008). Compared with nonleaders, military and business leaders have lower-than-average levels of stress hormones and report less anxiety, thanks to their greater sense of control (Sherman et al., 2012).

Compared with their parents’ generation, more young Americans now express an external locus of control (Twenge et al., 2004). This shift may help explain an associated increase in rates of depression and other psychological disorders in young people (Twenge et al., 2010).

Another way to say that we believe we are in control of our own life is to say we have free will. Studies show that people who believe they have free will learn better, perform better at work, and behave more helpfully (Job et al., 2010; Stillman et al., 2010). They also tend to enjoy making decisions, favor punishing rule breakers, and oppose behavior-restricting government regulations (Clark et al., 2014; Feldman et al., 2014; Hannikainen et al., 2016) These people also tend to demonstrate another type of control known as willpower or self-control—an important related topic we turn to next.

Building Self-Control

When we have a sense of personal control over our lives, we are more likely to develop self-control—the ability to control impulses and delay short-term gratification for longer-term rewards. Self-control predicts good health, higher income, and better school performance (Bub et al., 2016; Keller et al., 2016; Moffitt et al., 2011). In studies of American, Asian, and New Zealander children, self-control outdid intelligence test score in predicting future academic and life success (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005; Poulton et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016).

Strengthening self-control requires attention and energy—similar to strengthening a muscle. It’s easy to form bad habits, but it takes hard work to break them. With frequent practice in overcoming unwanted urges, people have strengthened their self-control, as seen in their improved self-management of anger, dishonesty, smoking, and impulsive spending (Beames et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017).

Extreme self-control Our ability to exert self-control increases with practice, and some of us have practiced more than others! A number of performing artists make their living as very convincing human statues, as does this actress performing on The Royal Mile in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Self-control varies over time. Like a muscle, it tends to weaken after use, recover after rest, and grow stronger with exercise (Baumeister & Vohs, 2016). In one famous experiment, hungry people who had spent some of their willpower resisting the temptation to eat chocolate chip cookies then abandoned a tedious task sooner than did others (Baumeister et al., 1998). Researchers are debating the reliability of this “depletion effect.” But the big lesson of self-control research remains: Develop self-discipline, and your self-control can help you have a healthier, happier, and more successful life (Tuk et al., 2015). The next time you face the temptation of studying versus having fun, remember that delaying a little fun now can lead to bigger future rewards.