Studying Memory

Memory is learning that persists over time; it is information that has been acquired and stored and can be retrieved. Research on memory’s extremes has helped us understand how memory works. At age 92, my [DM’s] father suffered a small stroke that had but one peculiar effect. He was as mobile as before. His genial personality was intact. He knew us and enjoyed poring over family photo albums and reminiscing about his past. But he had lost most of his ability to lay down new memories of conversations and everyday episodes. He could not tell me what day of the week it was, or what he’d had for lunch. Told repeatedly of his brother-in-law’s recent death, he was surprised and saddened each time he heard the news.

Extreme forgetting Alzheimer’s disease severely damages the brain, and in the process, strips away memory.

Some disorders slowly strip away memory. Alzheimer’s disease begins as difficulty remembering new information and progresses into an inability to do everyday tasks. Family members and close friends become strangers; complex speech devolves to simple sentences; the brain’s memory centers weaken and wither (Desikan et al., 2009). Over several years, someone with Alzheimer’s may become unknowing and unknowable. Lost memory strikes at the core of our humanity, leaving people robbed of a sense of joy, meaning, and companionship. (Without your memory, would you be you?)

At the other extreme are people who would win gold medals in a memory Olympics. Russian journalist Solomon Shereshevskii, or S, had merely to listen while other reporters scribbled notes (Luria, 1968). The average person could repeat back a string of about 7—maybe even 9—digits. S could repeat up to 70, if they were read about 3 seconds apart in an otherwise silent room. Moreover, he could recall digits or words backward as easily as forward. His accuracy was unerring, even when recalling a list 15 years later. “Yes, yes,” he might recall. “This was a series you gave me once when we were in your apartment. . . . You were sitting at the table and I in the rocking chair. . . . You were wearing a gray suit. . . .”

Amazing? Yes, but consider your own impressive memory. You remember countless faces, places, and happenings; tastes, smells, and textures; voices, sounds, and songs. In one study, students listened to snippets—a mere four-tenths of a second—from popular songs. How often did they recognize the artist and song? More than 25 percent of the time (Krumhansl, 2010). We often recognize songs as quickly as we recognize a familiar voice.

“ If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory.”

Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, 1814

So, too, with faces and places. Imagine viewing more than 2500 slides of faces and places for 10 seconds each. Later, you see 280 of these slides, paired with others you’ve never seen. Actual participants in this experiment recognized 90 percent of the slides they had viewed in the first round (Haber, 1970). In a follow-up experiment, people exposed to 2800 images for only 3 seconds each spotted the repeats with 82 percent accuracy (Konkle et al., 2010). Look for a target face in a sea of faces and you later will recognize other faces from the scene as well (Kaunitz et al., 2016). Some super-recognizers display an extraordinary ability to recognize faces. Eighteen months after viewing a video of an armed robbery, one such police officer spotted and arrested the robber walking on a busy street (Davis et al., 2013). And it’s not just humans who have shown remarkable memory for faces. Sheep can learn to remember faces (Figure 31.1). And so can at least one fish species—as demonstrated by their spitting at familiar faces to trigger a food reward (Newport et al., 2016).

Figure 31.1 Other animals also display face smarts

After food rewards are repeatedly associated with some sheep faces, but not with others, sheep remember the food-associated faces for two years (Kendrick & Feng, 2011).

How do we humans accomplish such memory feats? How does our brain pluck information out of the world around us and tuck it away for later use? How can we remember things we have not thought about for years, yet forget the name of someone we just met? How are memories stored in our brain? Why will you be likely, later in this module, to misrecall this sentence: “The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”? In this and the next two modules, we’ll consider these fascinating questions and more.

Measuring Retention

To a psychologist, evidence that learning persists includes these three retention measures:

- recall—retrieving information that is not currently in your conscious awareness but that was learned at an earlier time. A fill-in-the-blank question tests your recall.

- recognition—identifying items previously learned. A multiple-choice question tests your recognition.

- relearning—learning something more quickly when you learn it a second or later time. When you study for a final exam or engage a language used in early childhood, you will relearn the material more easily than you did initially.

Long after you cannot recall most of the people in your high school graduating class, you may still be able to recognize their yearbook pictures and spot their names in a list of names. In one experiment, people who had graduated 25 years earlier could not recall many of their old classmates. But they could recognize 90 percent of their pictures and names (Bahrick et al., 1975). If you are like most students, you, too, could probably recognize more names of Snow White’s seven dwarfs than you could recall (Miserandino, 1991).

Our recognition memory is impressively quick and vast. “Is your friend wearing a new or old outfit?” “Old.” “Is this five-second movie clip from a film you’ve ever seen?” “Yes.” “Have you ever seen this person before—this minor variation on the same old human features (two eyes, one nose, and so on)?” “No.” Before the mouth can form our answer to any of millions of such questions, the mind knows, and knows that it knows.

Our response speed when recalling or recognizing information indicates memory strength, as does our speed at relearning. Pioneering memory researcher Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909) showed this over a century ago, using nonsense syllables. He randomly selected a sample of syllables, practiced them, and tested himself. To get a feel for his experiments, rapidly read aloud, eight times over, the following list (from Baddeley, 1982), then look away and try to recall the items:

JIH, BAZ, FUB, YOX, SUJ, XIR, DAX, LEQ, VUM, PID, KEL, WAV, TUV, ZOF, GEK, HIW.

Remembering things past Even if Taylor Swift and Bruno Mars had not become famous, their high school classmates would most likely still recognize them in these photos.

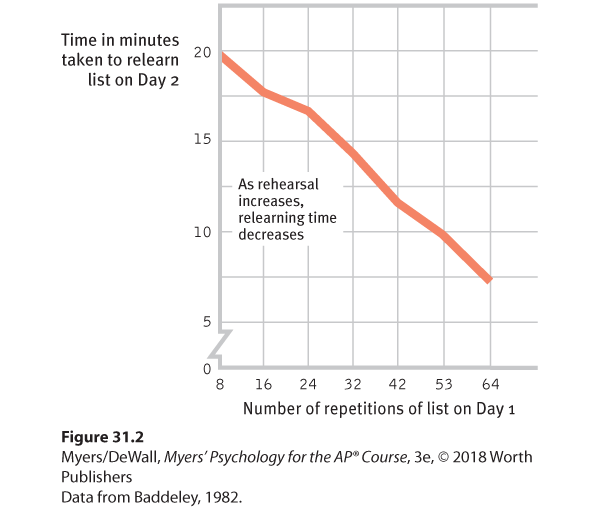

The day after learning such a list, Ebbinghaus could recall few of the syllables. But they weren’t entirely forgotten. As Figure 31.2 portrays, the more frequently he repeated the list aloud on Day 1, the less time he required to relearn the list on Day 2. Additional rehearsal of verbal information can produce overlearning, which increases retention—especially when practice is distributed over time. For students, this means that it helps to rehearse course material even after you know it.

Figure 31.2 Ebbinghaus’ retention curve

Ebbinghaus found that the more times he practiced a list of nonsense syllables on Day 1, the less time he required to relearn it on Day 2. Speed of relearning is one measure of memory retention.

The point to remember: Tests of recognition and of time spent relearning demonstrate that we remember more than we can recall.

Memory Models

Architects make virtual house models to help clients imagine their future homes. Similarly, psychologists create memory models that, even if imperfect, are useful. Such models help us think about how our brain forms and retrieves memories. An information-processing model likens human memory to computer operations. Thus, to remember any event, we must

- get information into our brain, a process called encoding.

- retain that information, a process called storage.

- later get the information back out, a process called retrieval.

Like all analogies, computer models have their limits. Our memories are less literal and more fragile than a computer’s. Most computers also process information sequentially, even while alternating between tasks. Our agile brain processes many things simultaneously (some of them unconsciously) by means of parallel processing. To focus on this multitrack processing, one information-processing model, connectionism, views memories as products of interconnected neural networks. Specific memories arise from particular activation patterns within these networks. Every time you learn something new, your brain’s neural connections change, forming and strengthening pathways that allow you to interact with and learn from your constantly changing environment.

To explain our memory-forming process, Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968, 2016) proposed a three-stage model:

- We first record to-be-remembered information as a fleeting sensory memory.

- From there, we process information into short-term memory, where we encode it through rehearsal.

- Finally, information moves into long-term memory for later retrieval.

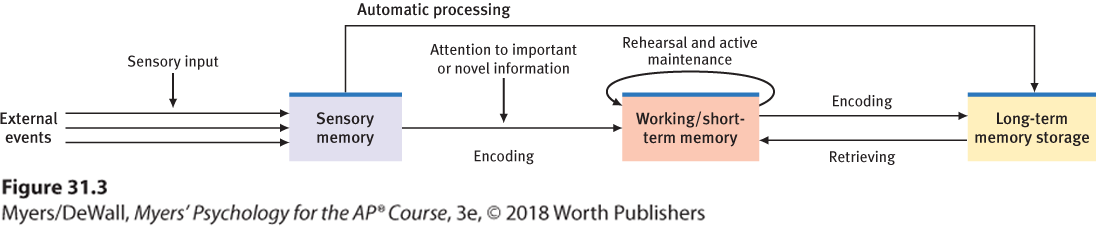

This model has since been updated (Figure 31.3) with important newer concepts, including working memory and automatic processing.

Figure 31.3 A modified three-stage processing model of memory

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s classic three-step model helps us to think about how memories are processed, but today’s researchers recognize other ways long-term memories form. For example, some information slips into long-term memory via a “back door,” without our consciously attending to it (automatic processing). And so much active processing occurs in the short-term memory stage that many now prefer the term working memory.

Working Memory

Alan Baddeley and others (Baddeley, 2002; Barrouillet et al., 2011; Engle, 2002) extended Atkinson and Shiffrin’s initial view of short-term memory as a space for briefly storing recent thoughts and experiences. This stage is not just a temporary shelf for holding incoming information. It’s an active scratchpad where your brain actively processes information by making sense of new input and linking it with long-term memories. It also works in the opposite direction, by processing already stored information. Whether we hear “eye-screem” as ice cream or I scream depends on how the context and our experience guide our interpreting and encoding of the sounds. To focus on the active processing that takes place in this middle stage, psychologists use the term working memory. Right now, you are using your working memory to link the information you’re reading with your previously stored information (Cowan, 2010, 2016; Kail & Hall, 2001).

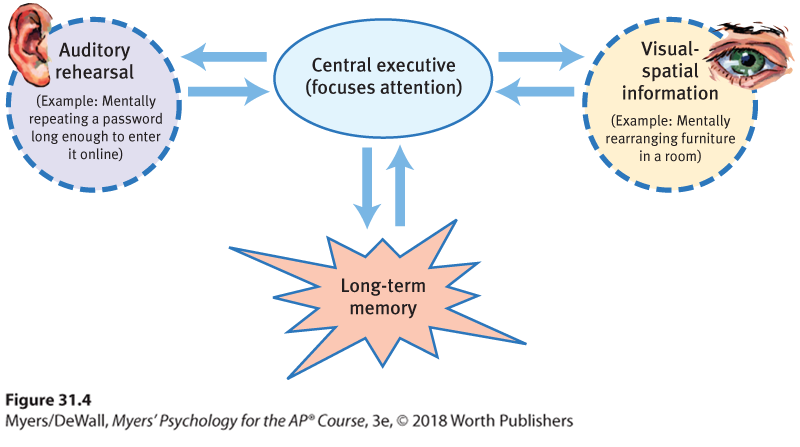

For most of you, what you are reading enters working memory through vision. You might also repeat the information using auditory rehearsal. As you integrate these memory inputs with your existing long-term memory, your attention is focused (recall from Module 16 the mental spotlight that we call selective attention). In Baddeley’s (2002) model, a central executive coordinates this focused processing (Figure 31.4).

Figure 31.4 Working memory

Alan Baddeley’s (2002) model of working memory, simplified here, includes visual and auditory rehearsal of new information. A hypothetical central executive (manager) focuses our attention, and pulls information from long-term memory to help make sense of new information.

Without focused attention, information often fades. If you think you can look something up later, you attend to it less and forget it more quickly. In one experiment, people read and typed new bits of trivia they would later need, such as “An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.” If they knew the information would be available online, they invested less energy and remembered it less well (Sparrow et al., 2011; Wegner & Ward, 2013). Online, out of mind.