Memory Storage

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, Sherlock Holmes offers a popular theory of memory capacity:

I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. . . . It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it, there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before.

Contrary to Holmes’ “memory model,” our brain is not like an attic, which once filled can store more items only if we discard old ones. Our capacity for storing long-term memories is essentially limitless. One research team, after studying the brain’s neural connections, estimated its storage capacity as “in the same ballpark as the World Wide Web” (Sejnowski, 2016).

Retaining Information in the Brain

I [DM] marveled at my aging mother-in-law, a retired pianist and organist. At age 88, her blind eyes could no longer read music. But let her sit at a keyboard and she would flawlessly play any of hundreds of hymns, including ones she had not thought of for 20 years. Where did her brain store those thousands of sequenced notes?

For a time, some surgeons and memory researchers marveled at patients’ apparently vivid memories triggered by brain stimulation during surgery. Did this prove that our whole past, not just well-practiced music, is “in there,” in complete detail, just waiting to be relived? On closer analysis, the seeming flashbacks appeared to have been invented, not a vivid reliving of long-forgotten experiences (Loftus & Loftus, 1980). In a further demonstration that memories do not reside in single, specific spots, psychologist Karl Lashley (1950) trained rats to find their way out of a maze, then surgically removed pieces of their brain’s cortex and retested their memory. No matter which small brain section he removed, the rats retained at least a partial memory of how to navigate the maze. Memories are brain-based, but the brain distributes the components of a memory across a network of locations. These specific locations include some of the circuitry involved in the original experience: Some brain cells that fire when we experience something fire again when we recall it (Miller, 2012a; Miller et al., 2013).

“ Our memories are flexible and superimposable, a panoramic blackboard with an endless supply of chalk and erasers.”

Elizabeth Loftus and Katherine Ketcham, The Myth of Repressed Memory, 1994

The point to remember: Despite the brain’s vast storage capacity, we do not store information as libraries store their books, in single, precise locations. Instead, brain networks encode, store, and retrieve the information that forms our complex memories.

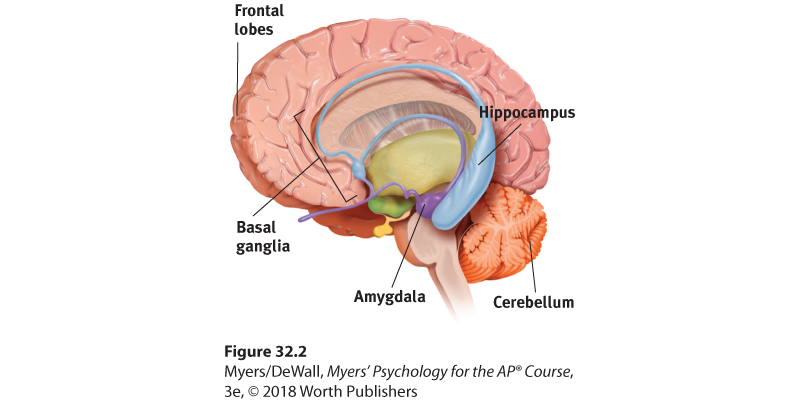

Explicit Memory System: The Frontal Lobes and Hippocampus

Explicit, conscious memories are either semantic (facts and general knowledge) or episodic (experienced events). The network that processes and stores new explicit memories for these facts and episodes includes your frontal lobes and hippocampus. When you summon up a mental encore of a past experience, many brain regions send input to your prefrontal cortex (the front part of your frontal lobes) for working memory processing (de Chastelaine et al., 2016; Michalka et al., 2015). The left and right frontal lobes process different types of memories. Recalling a password and holding it in working memory, for example, would activate the left frontal lobe. Calling up a visual party scene would more likely activate the right frontal lobe.

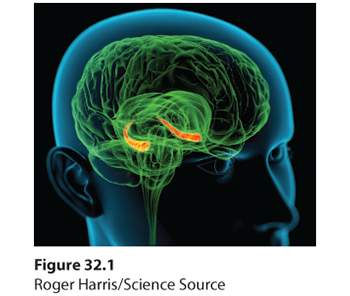

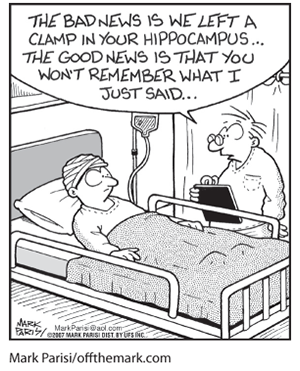

Cognitive neuroscientists have found that the hippocampus, a temporal-lobe neural center located in the limbic system, can be likened to a “save” button for explicit memories (Figure 32.1). Brain scans reveal activity in the hippocampus and nearby brain networks as people form explicit memories of names, images, and events (Squire & Wixted, 2011; Wang et al., 2014).

Figure 32.1 The hippocampus

Explicit memories for facts and episodes are processed in the hippocampus (orange structures) and fed to other brain regions for storage.

Damage to this structure therefore disrupts the formation and recall of explicit memories. If their hippocampus is severed, chickadees and other birds will continue to cache food in hundreds of places, but later be unable to find them (Kamil & Cheng, 2001; Sherry & Vaccarino, 1989). With left-hippocampus damage, people have trouble remembering verbal information, but they have no trouble recalling visual designs and locations. With right-hippocampus damage, the problem is reversed (Schacter, 1996).

Subregions of the hippocampus also serve different functions. One part is active as people and mice learn social information (Okuyama et al., 2016; Zeineh et al., 2003). Another part is active as memory champions engage in spatial mnemonics (Maguire et al., 2003a). The rear area, which processes spatial memory, grows bigger as London cabbies navigate the city’s complicated maze of streets (Woolett & Maguire, 2011).

Memories are not permanently stored in the hippocampus. Instead, this structure seems to act as a loading dock where the brain registers and temporarily holds the elements of a to-be-remembered episode—its smell, feel, sound, and location. Then, like older files shifted to a basement storeroom, memories migrate for storage elsewhere. This storage process is called memory consolidation. Removing a rat’s hippocampus 3 hours after it learns the location of some tasty new food disrupts this process and prevents long-term memory formation; removal 48 hours later does not (Tse et al., 2007).

Sleep supports memory consolidation. In one experiment, students who learned material in a study/sleep/restudy condition remembered material better both a week and six months later than those who studied in the morning and restudied in the evening without intervening sleep (Mazza et al., 2016). During deep sleep, the hippocampus processes memories for later retrieval. After a training experience, the greater one’s heart rate efficiency and hippocampus activity during sleep, the better the next day’s memory will be (Peigneux et al., 2004; Whitehurst et al., 2016). Researchers have watched the hippocampus and brain cortex displaying simultaneous activity rhythms during sleep, as if they were having a dialogue (Euston et al., 2007; Mehta, 2007). They suspect that the brain is replaying the day’s experiences as it transfers them to the cortex for long-term storage (Squire & Zola-Morgan, 1991). When our learning is distributed over days rather than crammed into a single day, we experience more sleep-induced memory consolidation. And that helps explain the spacing effect.

Hippocampus hero Among animals, one contender for champion memorist would be a mere birdbrain—the Clark’s Nutcracker—which during winter and spring can locate up to 6000 caches of pine seed it had previously buried (Shettleworth, 1993).

Implicit Memory System: The Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia

Your hippocampus and frontal lobes are processing sites for your explicit memories. But you could lose those areas and still, thanks to automatic processing, lay down implicit memories for skills and newly conditioned associations. Joseph LeDoux (1996) recounted the story of a brain-damaged patient whose amnesia left her unable to recognize her physician as, each day, he shook her hand and introduced himself. One day, she yanked her hand back, for the physician had pricked her with a tack in his palm. The next time he returned to introduce himself she refused to shake his hand but couldn’t explain why. Having been classically conditioned, she just wouldn’t do it. Implicitly, she felt what she could not explain.

The cerebellum plays a key role in forming and storing the implicit memories created by classical conditioning. With a damaged cerebellum, people cannot develop certain conditioned reflexes, such as associating a tone with an impending puff of air—and thus do not blink in anticipation of the puff (Daum & Schugens, 1996; Green & Woodruff-Pak, 2000). Implicit memory formation needs the cerebellum.

The basal ganglia, deep brain structures involved in motor movement, facilitate formation of our procedural memories for skills (Mishkin, 1982; Mishkin et al., 1997). The basal ganglia receive input from the cortex but do not return the favor of sending information back to the cortex for conscious awareness of procedural learning. If you have learned how to ride a bike, thank your basal ganglia.

Our implicit memory system, enabled by these more ancient brain areas, helps explain why the reactions and skills we learned during infancy reach far into our future. Yet as adults, our conscious memory of our first four years is largely blank, an experience called infantile amnesia. In one study, events children experienced and discussed with their mothers at age 3 were 60 percent remembered at age 7 but only 34 percent remembered at age 9 (Bauer et al., 2007). Two influences contribute to infantile amnesia: First, we index much of our explicit memory with a command of language that young children do not possess. Second, the hippocampus is one of the last brain structures to mature, and as it does, more gets retained (Akers et al., 2014).

The Amygdala, Emotions, and Memory

Our emotions trigger stress hormones that influence memory formation. When we are excited or stressed, these hormones make more glucose energy available to fuel brain activity, signaling the brain that something important is happening. Moreover, stress hormones focus memory. Stress provokes the amygdala (two limbic system, emotion-processing clusters) to initiate a memory trace that boosts activity in the brain’s memory-forming areas (Buchanan, 2007; Kensinger, 2007) (Figure 32.2). It’s as if the amygdala says, “Brain, encode this moment for future reference!” The result? Emotional arousal can sear certain events into the brain, while disrupting memory for irrelevant events (Brewin et al., 2007; McGaugh, 2015).

Figure 32.2 Review key memory structures in the brain

Frontal lobes and hippocampus: explicit memory formation Cerebellum and basal ganglia: implicit memory formation Amygdala: emotion-related memory formation

Significantly stressful events can form almost unforgettable memories. After a traumatic experience—a school shooting, a house fire, a rape—vivid recollections of the horrific event may intrude again and again. It is as if they were burned in: “Stronger emotional experiences make for stronger, more reliable memories,” noted James McGaugh (1994, 2003). Such experiences even strengthen recall for relevant, immediately preceding events (Dunsmoor et al., 2015: Jobson & Cheraghi, 2016). This makes adaptive sense: Memory serves to predict the future and to alert us to potential dangers. Emotional events produce tunnel vision memory. They focus our attention and recall on high priority information, and reduce our recall of irrelevant details (Mather & Sutherland, 2012). Whatever rivets our attention gets well recalled, at the expense of the surrounding context.

Emotion-triggered hormonal changes help explain why we long remember exciting or shocking events, such as our first kiss or our whereabouts when learning of a loved one’s death. In a 2006 Pew survey, 95 percent of American adults said they could recall exactly where they were or what they were doing when they first heard the news of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. This perceived clarity of memories of surprising, significant events (where were you when learning that Donald Trump was elected U.S. president?) leads some psychologists to call them flashbulb memories.

The people who experienced a 1989 San Francisco earthquake had perfect recall, a year and a half later, of where they had been and what they were doing (verified by their recorded thoughts within a day or two of the quake). Others’ memories for the circumstances under which they merely heard about the quake were more prone to errors (Neisser et al., 1991; Palmer et al., 1991).

Our flashbulb memories are noteworthy for their vividness and our confidence in them. But as we relive, rehearse, and discuss them, even these memories may come to err. With time, some errors crept into people’s 9/11 recollections (compared with their earlier reports taken right after 9/11). Mostly, however, people’s memories of 9/11 remained consistent over the next two to three years (Conway et al., 2009; Hirst et al., 2009).

Dramatic experiences remain clear in our memory in part because we rehearse them (Hirst & Phelps, 2016). We think about them and describe them to others. Memories of our best experiences, which we enjoy recalling and recounting, also endure (Storm & Jobe, 2012; Talarico & Moore, 2012). One study invited 1563 Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees fans to recall the baseball championship games between their two teams in 2003 (Yankees won) and 2004 (Red Sox won). Fans recalled much better the game their team won (Breslin & Safer, 2011).

Synaptic Changes

As you read this module and think and learn about memory processes, your brain is changing. Given increased activity in particular pathways, neural interconnections are forming and strengthening.

The quest to understand the physical basis of memory—how information becomes embedded in brain matter—has sparked study of the synaptic meeting places where neurons communicate with one another via their neurotransmitter messengers. Eric Kandel and James Schwartz (1982) observed synaptic changes during learning in the neurons of the California sea slug, Aplysia, a simple animal with a mere 20,000 or so unusually large and accessible nerve cells. Module 26 noted how the sea slug can be classically conditioned (with electric shock) to reflexively withdraw its gills when squirted with water, much as a soldier traumatized by combat might jump at the sound of a firecracker. When learning occurs, Kandel and Schwartz discovered, the slug releases more of the neurotransmitter serotonin into certain neurons. These cells’ synapses then become more efficient at transmitting signals. Experience and learning can increase—even double—the number of synapses, even in slugs (Kandel, 2012).

Aplysia The California sea slug, which neuroscientist Eric Kandel studied for 45 years, has increased our understanding of the neural basis of learning and memory.

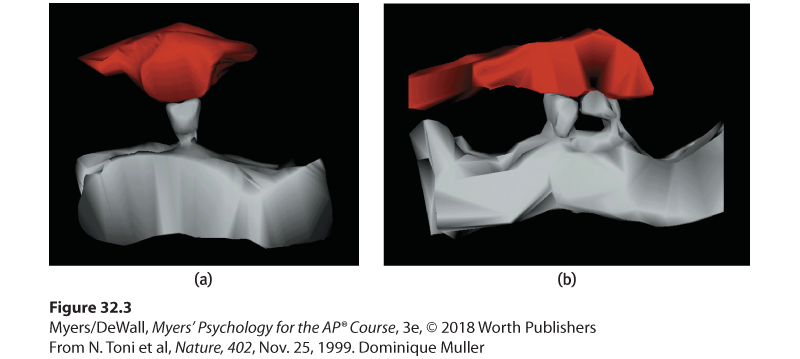

In experiments with people, rapidly stimulating certain memory-circuit connections has increased their sensitivity for hours or even weeks to come. The sending neuron now needs less prompting to release its neurotransmitter, and more connections exist between neurons. This increased efficiency of potential neural firing, called long-term potentiation (LTP), provides a neural basis for learning and remembering associations (Lynch, 2002; Whitlock et al., 2006) (Figure 32.3). Several lines of evidence confirm that LTP is a physical basis for memory:

- Drugs that block LTP interfere with learning (Lynch & Staubli, 1991).

- Drugs that mimic what happens during learning increase LTP (Harward et al., 2016).

- Rats given a drug that enhanced LTP learned a maze with half the usual number of mistakes (Service, 1994).

Figure 32.3 Doubled receptor sites

An electron microscope image (a) shows just one receptor site (gray) reaching toward a sending neuron before long-term potentiation. Image (b) shows that, after LTP, the receptor sites have doubled. This means the receiving neuron has increased sensitivity for detecting the presence of the neurotransmitter molecules that may be released by the sending neuron (Toni et al., 1999).

Flip It Video: Long-Term Potentiation

Flip It Video: Long-Term Potentiation

After LTP has occurred, passing an electric current through the brain won’t disrupt old memories. But the current will wipe out very recent memories. Such is the experience both of laboratory animals and of severely depressed people given electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (see Module 73). A blow to the head can do the same. Football players and boxers momentarily knocked unconscious typically have no memory of events just before the knockout (Yarnell & Lynch, 1970). Their working memory had no time to consolidate the information into long-term memory before the lights went out.

Recently, I [DM] did a little test of memory consolidation. While on an operating table for a basketball-related tendon repair, I was given a face mask and soon could smell the anesthesia gas. “So how much longer will I be with you?” I asked the anesthesiologist. My last moment of memory was her answer: “About 10 seconds.” My brain spent that 10 seconds consolidating a memory for her 2-second answer, but could not tuck any further memory away before I was out cold.

Some memory-biology explorers have helped found companies that are competing to develop memory-altering drugs. The target market for memory-boosting drugs includes millions of people with Alzheimer’s disease, millions more with mild cognitive impairment that often becomes Alzheimer’s, and countless millions who would love to turn back the clock on age-related memory decline. Meanwhile, one safe and free memory enhancer is already available for high schoolers everywhere: study followed by adequate sleep! (You’ll find study tips in Module 2 and at the end of this module, and sleep coverage in Modules 23 and 24.)

One approach to improving memory focuses on drugs that boost the LTP-enhancing neurotransmitter glutamate (Lynch et al., 2011). Another approach involves developing drugs that boost production of CREB, a protein that also enhances the LTP process (Fields, 2005). Boosting CREB production might trigger increased production of other proteins that help reshape synapses and transfer short-term memories into long-term memories.

Some of us may wish for memory-blocking drugs that, when taken after a traumatic experience, might blunt intrusive memories (Adler, 2012; Kearns et al., 2012). In one experiment, victims of car accidents, rapes, and other traumas received, for 10 days following their horrific event, either one such drug, propranolol, or a placebo. When tested three months later, half the placebo group but none of the drug-treated group showed signs of stress (Pitman & Delahanty, 2005; Pitman et al., 2002).

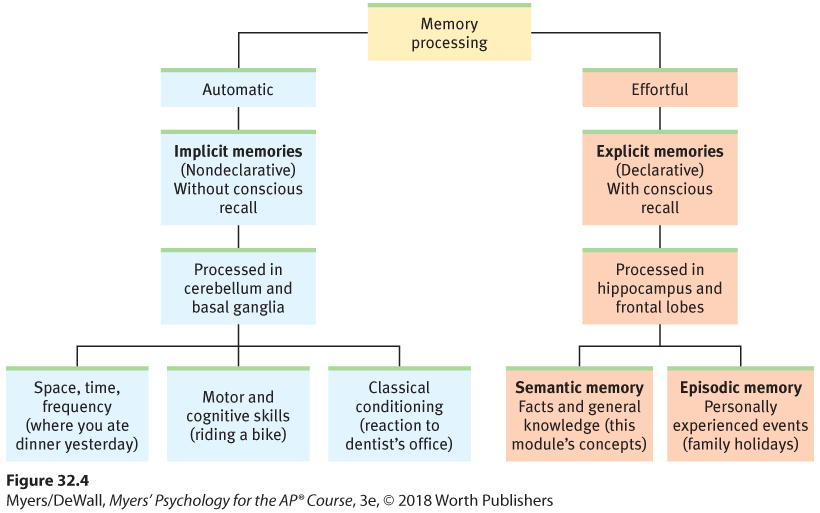

Figure 32.4 summarizes the brain’s two-track memory processing and storage system for implicit (automatic) and explicit (effortful) memories. The bottom line: Learn something and you change your brain a little.

Figure 32.4 Our two memory systems