Concepts

Flip It Video: Concepts & Prototypes

Flip It Video: Concepts & Prototypes

Psychologists who study cognition focus on the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating information. One of these activities is forming concepts—mental groupings of similar objects, events, ideas, or people. The concept chair includes many items—a baby’s high chair, a reclining chair, a dentist’s chair—all for sitting. Concepts simplify our thinking. Imagine life without them. We could not ask a child to “throw the ball” because there would be no concept of throw or ball. Instead of saying, “They were angry,” we would have to describe expressions, intensities, and words. Concepts such as ball and anger give us much information with little cognitive effort.

“Attention, everyone! I’d like to introduce the newest member of our family.”

We often form our concepts by developing prototypes—a mental image or best example of a category (Rosch, 1978). People more quickly agree that “a crow is a bird” than that “a penguin is a bird.” For most of us, the crow is the birdier bird; it more closely resembles our bird prototype. Similarly, for people in modern multiethnic Germany, Caucasian Germans are more prototypically German (Kessler et al., 2010). When something closely matches our prototype of a concept—such as a bird or a German—we more readily recognize it as an example of the concept.

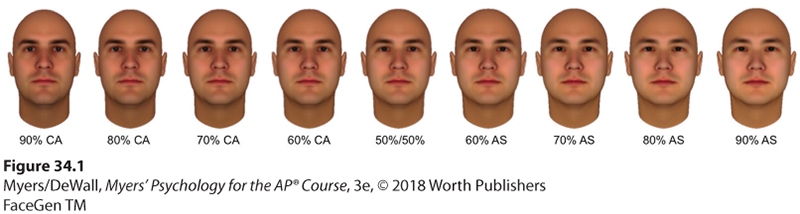

When we categorize people, we mentally shift them toward our category prototypes. Such was the experience of Belgian students who viewed ethnically blended faces. When viewing a blended face in which 70 percent of the features were Caucasian and 30 percent were Asian, the students categorized the face as Caucasian (Figure 34.1). Later, as their memory shifted toward the Caucasian prototype, they were more likely to remember an 80 percent Caucasian face than the 70 percent Caucasian face they had actually seen (Corneille et al., 2004). Likewise, if shown a 70 percent Asian face, they later remembered a more prototypically Asian face. So, too, with gender: People who viewed 70 percent male faces categorized them as male (no surprise there) and then later misremembered them as even more prototypically male (Huart et al., 2005).

Figure 34.1 Categorizing faces influences recollection

Shown a face that was 70 percent Caucasian, people tended to classify the person as Caucasian and to recollect the face as more Caucasian than it was. (Recreation of experiment courtesy of Olivier Corneille.)

Move away from our prototypes, and category boundaries may blur. Is a tomato a fruit? Is a 16-year-old female a girl or a woman? Is a whale a fish or a mammal? Because a whale fails to match our mammal prototype, we are slower to recognize it as a mammal. Similarly, when symptoms don’t fit one of our disease prototypes, we are slow to perceive an illness (Bishop, 1991). People whose heart attack symptoms (shortness of breath, exhaustion, a dull weight in the chest) don’t match their heart attack prototype (sharp chest pain) may not seek help. And when behaviors don’t fit our discrimination prototypes—of White against Black, male against female, young against old—we often fail to notice prejudice. People more easily detect male prejudice against females than female against males or female against females (Cunningham et al., 2009; Inman & Baron, 1996). Although concepts speed and guide our thinking, they don’t always make us wise.