Drives and Incentives

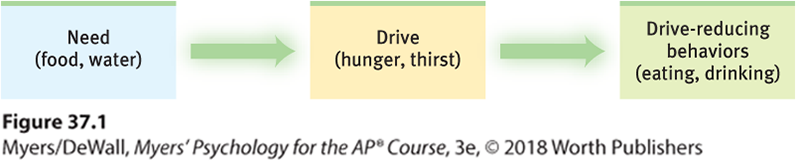

In addition to our predispositions, we have drives. Physiological needs (such as for food or water) create an aroused, motivated state—a drive (such as hunger or thirst)—that pushes us to reduce the need. Drive-reduction theory explains that, with few exceptions, when a physiological need increases, so does our psychological drive to reduce it.

Drive reduction is one way our bodies strive for homeostasis (literally “staying the same”)—the maintenance of a steady internal state. For example, our body regulates its temperature in a way similar to a room’s thermostat. Both systems operate through feedback loops: Sensors feed room temperature to a control device. If the room’s temperature cools, the control device switches on the furnace. Likewise, if our body’s temperature cools, our blood vessels constrict to conserve warmth, and we feel driven to put on more clothes or seek a warmer environment (Figure 37.1).

Figure 37.1 Drive-reduction theory

Drive-reduction motivation arises from homeostasis—an organism’s natural tendency to maintain a steady internal state. Thus, if we are water deprived, our thirst drives us to drink and to restore the body’s normal state.

Not only are we pushed by our need to reduce drives, we also are pulled by incentives—positive or negative environmental stimuli that lure or repel us. Given such stimuli, our underlying drives, such as for food or love, become active impulses. And the more those impulses are satisfied and reinforced, the stronger the drive may become: As Roy Baumeister (2015) noted, “Getting begets wanting.” Thus, our learning influences our motives. Depending on our learning, the aroma of good food, whether roasted peanuts or toasted ants, can motivate our behavior. So can the sight of those we find attractive or threatening.

When there is both a need and an incentive, we feel strongly driven. The food-deprived person who smells pizza baking may feel a strong hunger drive, and the baking pizza may become a compelling incentive. For each motive, we can therefore ask, “How is it pushed by our inborn physiological needs and pulled by learned incentives in the environment?” (Remember from Module 29 that both extrinsic and intrinsic rewards motivate us. Thus, making a pizza may be either a means to an extrinsic paycheck, or an intrinsically satisfying home-baked pleasure.)