Arousal Theory

We are much more than calm homeostatic systems, however. Some motivated behaviors actually increase arousal. Well-fed animals will leave their shelter to explore and gain information, seemingly in the absence of any need-based drive. Curiosity drives monkeys to monkey around trying to figure out how to unlock a latch that opens nothing or how to open a window that allows them to see outside their room (Butler, 1954). Curiosity drives newly mobile infants to investigate every accessible corner of the house, and it drove students, in one experiment, to click on pens to see whether they did or didn’t deliver an electric shock (Hsee & Ruan, 2016). It drives you to read this text; it drives the scientists whose work this text discusses. And it drives explorers and adventurers such as mountaineer George Mallory. Asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, Mallory famously answered, “Because it’s there.” Sometimes uncertainty brings excitement, which amplifies motivation (Shen et al., 2015). Those who, like Mallory, enjoy high arousal are most likely to seek out intense music, novel foods, and risky behaviors and careers (Roberti et al., 2004; Zuckerman, 1979, 2009). Although they have been called “sensation-seekers,” risk takers may also be motivated to master their emotions and actions (Barlow et al., 2013).

Driven by curiosity Young monkeys and children are fascinated by the unfamiliar. Their drive to explore maintains an optimum level of arousal and is one of several motives that do not fill any immediate physiological need.

So, human motivation aims not to eliminate arousal but to seek optimum levels of arousal. Having all our biological needs satisfied, we feel driven to experience stimulation. Lacking stimulation, we feel bored and look for a way to increase arousal. If left alone in a room, most people prefer to do something—even (when given no other option) to self-administer mild electric shocks (Wilson et al., 2014). Moderate anxiety can be motivating—leading to higher levels of math achievement, for example (Wang, Z., et al., 2015). However, given too much stimulation or stress, we look for a way to decrease arousal. In one experiment, people felt less stress when they cut back checking e-mail to three times a day rather than being continually accessible (Kushlev & Dunn, 2015).

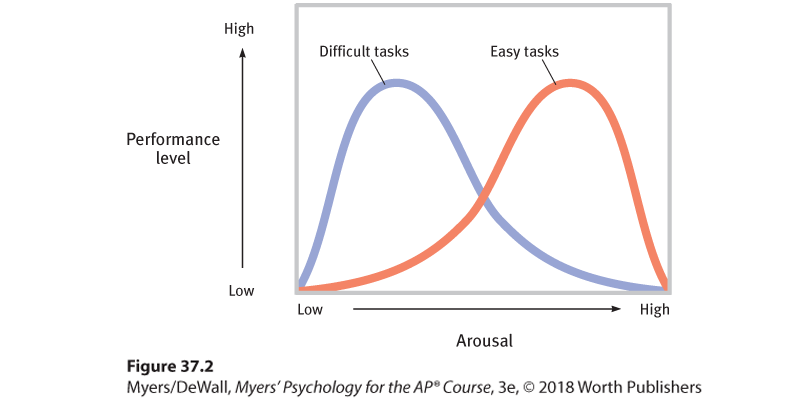

Two early twentieth-century psychologists studied the relationship of arousal to performance and identified the Yerkes-Dodson law: moderate arousal leads to optimal performance (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). When taking a test, for example, it pays to be moderately aroused—alert but not trembling with nervousness. (If already anxious, it’s better not to become further aroused with caffeine.) Between bored low arousal and anxious hyperarousal lies a flourishing life. Optimal arousal levels depend on the task, with more difficult tasks requiring lower arousal for best performance (Hembree, 1988) (Figure 37.2).

Figure 37.2 Arousal and performance