The Need to Belong

Separated from friends or family—alone in prison or at a new school or in a foreign land—most people feel keenly their lost connections with important others. We are what the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle called the social animal. The more people connect with friends, the greater their satisfaction with life (Li & Kanazawa, 2016). “Without friends,” wrote Aristotle in his Nichomachean Ethics, “no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods.” This deep need to belong—our affiliation need—seems a key human motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Mark Zuckerberg (2012) understands this, noting that he founded Facebook “to accomplish a social mission—to make the world more open and connected.” Although people vary in their wish for privacy and solitude, most of us seek to affiliate—to become strongly attached to certain others in enduring, close relationships. Human beings, contended personality theorist Alfred Adler, have an “urge to community” (Ferguson, 1989, 2001, 2010).

The Benefits of Belonging

Social bonds boosted our early ancestors’ chances of survival. Adults who formed attachments were more likely to survive, to reproduce, and to co-nurture their offspring to maturity. Attachment bonds motivated caregivers to keep children close, calming them and protecting them from threats (Esposito et al., 2013). Indeed, to be “wretched” literally means, in its Middle English origin (wrecched), to be without kin nearby.

Cooperation also enhanced survival. In solo combat, our ancestors were not the toughest predators. But as hunters, they learned that six hands were better than two. As food gatherers, they gained protection from two-footed and four-footed enemies by traveling in groups. Those who felt a need to belong survived and reproduced most successfully, and their genes now predominate. Our innate need to belong drives us to befriend people who cooperate and to avoid those who exploit (Feinberg et al., 2014). People in every society on Earth belong to groups and (as Module 77 explains) prefer and favor “us” over “them.” Having a social identity—feeling part of a group—boosts people’s health and well-being (Allen et al., 2015; Greenaway et al., 2015, 2016).

Do you have close friends—people with whom you freely disclose your ups and downs? Having someone who rejoices with us over good news helps us feel better about both the news and the friendship (Reis et al., 2010). A stranger’s casual thank-you can warm our heart (Williams & Bartlett, 2015). And close friends can literally make us feel warm, as if we are holding a soothing bowl of warm soup (Inagaki & Eisenberger, 2013). The need to belong runs deeper, it seems, than any need to be rich. One study found that very happy university students were distinguished not by their money but by their “rich and satisfying close relationships” (Diener & Seligman, 2002).

The need to belong colors our thoughts and emotions. We spend a great deal of time thinking about actual and hoped-for relationships. When relationships form, we often feel joy. Falling in mutual love, people have been known to feel their cheeks ache from their irrepressible grins. Asked, “What is necessary for your happiness?” or “What is it that makes your life meaningful?” most people have mentioned—before anything else—close, satisfying relationships with family, friends, or romantic partners (Berscheid, 1985). Happiness hits close to home.

Consider: What was your most satisfying moment in the past week? Researchers asked that question of American and South Korean university students, then asked them to rate how much that moment had satisfied various needs (Sheldon et al., 2001). In both countries, the peak moment had satisfied self-esteem and relatedness-belonging needs. When we satisfy our need for relatedness in balance with two other basic psychological needs—autonomy (a sense of personal control) and competence—we experience a deep sense of well-being, our performance improves, and our self-esteem rides high (Cerasoli et al., 2016; Deci & Ryan, 2009; Milyavskaya et al., 2009). Indeed, self-esteem is a gauge of how valued and accepted we feel (Leary, 2012).

Small wonder, then, that our social behavior so often aims to increase our feelings of belonging. To gain acceptance, we generally conform to group standards. We wait in lines and obey laws. We monitor our behavior, hoping to make a good impression. We spend billions on clothes, cosmetics, and diet and fitness aids—all motivated by our search for love and acceptance.

Thrown together in groups at school, at band camp, or in team sports, we form bonds. Parting, we feel distress. We promise to call, to write, to return for reunions. By drawing a sharp circle around “us,” the need to belong feeds both deep attachments to those inside the circle (loving families, faithful friendships, and team loyalty) and hostilities toward those outside (teen gangs, ethnic rivalries, and fanatic nationalism). Feelings of love activate brain reward and safety systems. In one experiment, deeply in love university students exposed to heat felt less pain when looking at their beloved’s picture (Younger et al., 2010). Pictures of our loved ones also activate a brain region—the prefrontal cortex—that dampens feelings of physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2011). Love is a natural painkiller.

Even when bad relationships end, people suffer. In one 16-nation survey, and in repeated U.S. surveys, separated and divorced people have been half as likely as married people to say they are “very happy” (Inglehart, 1990; NORC, 2016a). Is that simply because happy people more often marry and stay married? A national study following British lives through time revealed that, even after controlling for premarital life satisfaction, “the married are still more satisfied, suggesting a causal effect” of marriage (Grover & Helliwell, 2014). Divorce also predicts earlier mortality. Studies that have followed 6.5 million people in 11 countries reveal that, compared with married people, separated and divorced people are at greater risk for early death (Sbarra et al., 2011).

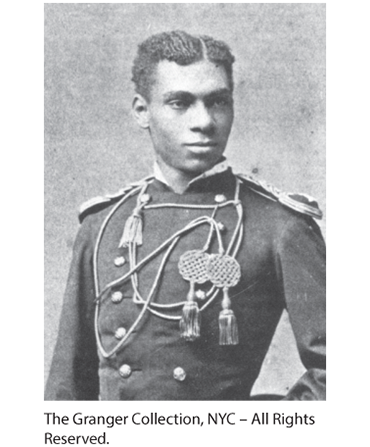

The need to connect Six days a week, women from the Philippines work as domestic helpers in thousands of Hong Kong households. On Sundays, they throng to the central business district to picnic, dance, sing, talk, and laugh. “Humanity could stage no greater display of happiness,” reported one observer (The Economist, 2001).

Children who move through a series of foster homes or through regular family relocations know the fear of being alone. After repeated disruption of budding attachments, they may have difficulty forming deep relationships (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010b). The evidence is clearest at the extremes. As we will see in Module 48, children who grow up in institutions without a sense of belonging to anyone, or who are locked away at home and severely neglected tend to become withdrawn, frightened, even speechless. Feeling insecurely attached to others during childhood can persist into adulthood in two main forms (Fraley et al., 2011). One is anxiety: constantly craving acceptance but remaining vigilant to signs of possible rejection. The other is avoidance: feeling such discomfort over getting close to others that avoidant strategies are used to maintain distance.

No matter how secure our early years were, we all experience anxiety, loneliness, jealousy, or guilt when something threatens or dissolves our social ties. Much as life’s best moments occur when close relationships begin—making a new friend, falling in love, having a baby—life’s worst moments happen when close relationships end (Beam et al., 2016). Bereaved, we may feel life is empty or pointless, and we may overeat to fill that emptiness (Yang et al., 2016). Even the first months of living away from home on a college campus can be distressing (English et al., 2017). But our need to belong pushes us to form new social connections (Oishi et al., 2013).

For immigrants and refugees moving alone to new places, the stress and loneliness can be depressing. After years of placing individual families in isolated communities, many government policy makers began to see the wisdom of encouraging chain migration (Pipher, 2002). The second Syrian refugee family settling in a town generally has an easier adjustment than the first.

Social isolation can put us at risk for mental decline and ill health (Cacioppo et al., 2015). Older adults make more doctor visits, if lonely, and are at greater risk for dementia (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, 2015; Holwerda et al., 2014). But if feelings of acceptance and connection increase sufficiently, so will self-esteem, positive feelings, and physical health (Blackhart et al., 2009; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Smart Richman & Leary, 2009). A socially connected life is often a happy and healthy life.

“ Just give me the death penalty, man.”

Paul Redd, from solitary confinement, 2015

The Pain of Being Shut Out

Can you recall feeling excluded or ignored or shunned? Perhaps you were unfriended or ignored online. Perhaps others gave you the silent treatment, avoided you, looked away, mocked you, or shut you out in some other way. Or perhaps you have felt excluded when among people speaking an unfamiliar language (Dotan-Eliaz et al., 2009).

All these experiences are instances of ostracism—of social exclusion (Williams, 2007, 2009). Worldwide, humans use many forms of ostracism—exile, imprisonment, solitary confinement—to punish, and therefore control, social behavior. For children, even a brief time-out in isolation can be punishing. Asked to describe personal episodes that made them feel especially bad about themselves, people will—about four times in five—describe a broken or painful social relationship (Pillemer et al., 2007).

Being shunned threatens one’s need to belong (Vanhalst et al., 2015; Wirth et al., 2010). “It’s the meanest thing you can do to someone, especially if you know they can’t fight back. I never should have been born,” said Lea, a lifelong victim of the silent treatment by her mother and grandmother. Like Lea, people often respond to ostracism with initial efforts to restore their acceptance, with depressed moods, and finally with withdrawal. Prisoner William Blake (2013) has spent more than a quarter-century in solitary confinement. “I cannot fathom how dying any death could be harder and more terrible than living through all that I have been forced to endure,” he observed. To many, social exclusion is a sentence worse than death.

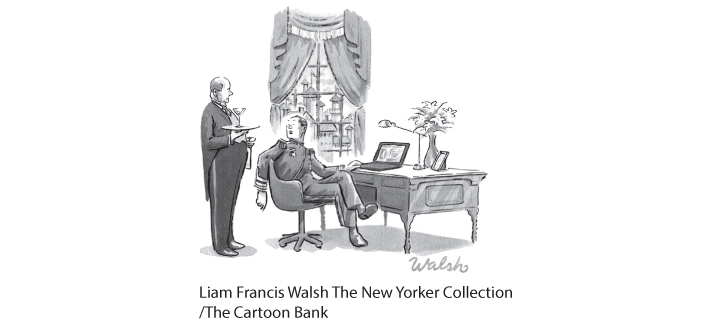

Enduring the pain of ostracism White cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point ostracized Henry Flipper for years, hoping he would drop out. He persevered in spite of their cruelty and in 1877 became the first African-American West Point graduate.

To experience ostracism is to experience real pain, as social psychologists Kipling Williams and his colleagues were surprised to discover in their studies of exclusion on social media (Gonsalkorale & Williams, 2006). (Perhaps you can recall the feeling of having few followers on a social networking site, or of having a text message or e-mail go unanswered.) Such ostracism, they discovered, takes a toll: It elicits increased activity in brain areas, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, that also respond to physical pain (Eisenberger, 2015; Rotge et al., 2015).

When people view pictures of romantic partners who caused their hearts to break, their brains and bodies begin to ache (Kross et al., 2011). That helps explain another surprising finding: The pain reliever acetaminophen (as in Tylenol) lessens social as well as physical pain (DeWall et al., 2010). Across cultures, people use the same words (for example, hurt, crushed) for social pain and physical pain (MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Psychologically, we seem to experience social pain with the same emotional unpleasantness that marks physical pain.

Pain, whatever its source, focuses our attention and motivates corrective action. Rejected and unable to remedy the situation, people may relieve stress by seeking new friends, eating calorie-laden comfort foods, or strengthening their religious faith (Aydin et al., 2010; Maner et al., 2007; Sproesser et al., 2014). Or they may turn hostile. Ostracism breeds disagreeableness, which leads to further ostracism (Hales et al., 2016). In one series of experiments, researchers told some students (who had taken a personality test) that they were “the type likely to end up alone later in life,” or that people they had met didn’t want them in a group that was forming (Gaertner et al., 2008; Twenge et al., 2001).1 They told other students that they would have “rewarding relationships throughout life,” or that “everyone chose you as someone they’d like to work with.” Those who were excluded became much more likely to engage in self-defeating behaviors and to act in disparaging or aggressive ways against those who had excluded them (blasting them with noise, for example). “If intelligent, well-adjusted, successful . . . students can turn aggressive in response to a small laboratory experience of social exclusion,” noted the research team, “it is disturbing to imagine the aggressive tendencies that might arise from . . . chronic exclusion from desired groups in actual social life.” Indeed, as Williams (2007) has observed, ostracism “weaves through case after case of school violence.”

Social acceptance and rejection Successful participants on the reality TV show Survivor form alliances and gain acceptance among their peers. The rest receive the ultimate social punishment as they are “voted off the island.”

“ If no one turned around when we entered, answered when we spoke, or minded what we did, but if every person we met ‘cut us dead,’ and acted as if we were non-existing things, a kind of rage and impotent despair would ere long well up in us.”

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890/1950, pp. 293–294

Connecting and Social Networking

As social creatures, we live for connection. Researcher George Vaillant (2013) was asked what he had learned from studying 238 Harvard University men from the 1930s to the end of their lives. He replied, “Happiness is love.” A South African Zulu saying captures the idea: Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu—“a person is a person through other persons.”

Mobile Networks and Social Media

Look around and see humans connecting: talking, tweeting, texting, posting, chatting, social gaming, e-mailing. Walking from class to class, you may see students glued to their phones, making little eye contact with passersby (or perhaps that’s you?). During class breaks, do you observe students getting to know each other—or silently checking their phones, as one research team’s phone app counted college students doing 56 times a day (Elias et al., 2016)? The changes in how we connect have been fast and vast.

- MOBILE PHONES. At the end of 2016, 95 percent of the world’s 7.5 billion people lived in an area covered by a mobile-cellular network (ITU, 2016).

- TEXTS. The typical U.S. teen with a cell phone sends 30 texts a day (Lenhart, 2015). Half of 18- to 29-year-olds with a cell phone check it multiple times per hour, and “can’t imagine . . . life without [it]” (Newport, 2015; Saad, 2015).

- THE INTERNET. Worldwide in 2015, 68 percent of adults used the Internet (Poushter, 2016).

- SOCIAL NETWORKING. Among 2014’s entering American college students, 94 percent were using social networking sites (Eagan et al., 2014). With one’s friends online, it’s hard not to be: Check in or miss out.

The Net Result: Social Effects of Social Networking

By connecting like-minded people, the Internet serves as a social amplifier. In times of social crisis or personal stress, it provides information and supportive connections. It enables people to share their experiences and compare their lives with others, though it can be depressing when one garners few likes or has lots of bragging friends (Blease, 2015; Verduyn et al., 2015). The Internet also functions as an online matchmaker (as I [ND] can attest: I met my wife online; more on this in Module 79). Dating websites aren’t right for everyone, but they can effectively match partners who share desired characteristics (Bruch et al., 2016). As electronic communication has become an integral part of life, researchers continue to explore how it affects our relationships. Online networking is double-edged: Nature has designed us for face-to-face relationships, and those who spend hours online are less likely to know and draw help from their real-world neighbors. But it does help us connect with friends, stay in touch with extended family, and find support when facing challenges (Liu et al., 2016; Pinker, 2014; Rainie et al., 2011). When used in moderation, social networking predicts longer life (Hobbs et al., 2016).

DOES ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATION STIMULATE HEALTHY SELF-DISCLOSURE?

Self-disclosure is sharing ourselves—our joys, worries, and weaknesses—with others. As we will see later in this unit, confiding can be a healthy way of coping with day-to-day challenges. When communicating electronically rather than face-to-face, we often are less focused on others’ reactions. We are less self-conscious and thus less inhibited. Sometimes this is taken to an extreme, as when bullies hound a victim, hate groups post messages promoting bigotry or crimes, or teens send photos of themselves they later regret. More often, however, the increased self-disclosure serves to deepen friendships (Valkenburg & Peter, 2009).

“The women on these dating sites don’t seem to believe I’m a prince.”

DOES SOCIAL NETWORKING PROMOTE NARCISSISM?

Narcissism is self-esteem gone wild. Narcissistic people are self-important, self-focused, and self-promoting. Personality tests may assess narcissism with items such as “I like to be the center of attention.” People with high narcissism test scores are especially active on social networking sites (Liu & Baumeister, 2016). They collect more superficial “friends.” They offer more staged, glamorous photos. They retaliate more against negative comments. And, not surprisingly, they seem more narcissistic to strangers (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Weiser, 2015).

For narcissists, social networking sites are more than a gathering place; they are a feeding trough. In one study, college students were randomly assigned either to edit and explain their online profiles for 15 minutes, or to use that time to study and explain a Google Maps routing (Freeman & Twenge, 2010). After completing their tasks, all were tested. Who then scored higher on a narcissism measure? Those who had spent the time focused on themselves.

Maintaining Balance and Focus

In both Taiwan and the United States, excessive online socializing and gaming have correlated with lower grades or increased anxiety and depression (Brooks, 2015; Lepp et al., 2014; Walsh et al., 2013). In one U.S. survey, 47 percent of the heaviest users of the Internet and other media were receiving mostly C grades or lower, as were just 23 percent of the lightest users (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). In another national survey, young adults who used seven or more social media platforms were three times more likely to be depressed or anxious than those who used two or fewer (Primack et al., 2016).

In today’s world, most of us are challenged to maintain a healthy balance between our real-world and online time. Experts offer some practical suggestions:

- MONITOR YOUR TIME. Keep a log of how you use your time. Then ask yourself, “Does my time use reflect my priorities? Am I spending more or less time online than I intended? Is my time online interfering with my school or work performance or relationships? Have family or friends commented on this?”

- MONITOR YOUR FEELINGS. Ask yourself, “Am I emotionally distracted by my online interests? When I disconnect and move to another activity, how do I feel?”

- “HIDE” FROM YOUR INCESSANTLY POSTING ONLINE FRIENDS WHEN NECESSARY. And in your own postings, practice the golden rule: Ask yourself, “Is this something I’d care about if someone else posted it?”

- WHEN STUDYING, GET IN THE HABIT OF CHECKING YOUR PHONE AND E-MAIL LESS OFTEN. Selective attention—the flashlight of your mind—can be in only one place at a time. When we try to do two things at once, we don’t do either one of them very well (Willingham, 2010). If you want to study or work productively, resist the temptation to always be available. Disable sound alerts, vibration, and pop-ups. In one experiment, randomly selected people who kept their e-mail closed and checked e-mail just three times a day enjoyed a significant reduction in stress (Kushlev & Dunn, 2015). (To avoid distraction, I [DM] am proofing and editing this unit in a coffee shop without Wi-Fi.)

- REFOCUS BY TAKING A NATURE WALK. People learn better after a peaceful walk in a park, which—unlike a walk on a busy street—refreshes our capacity for focused attention (Berman et al., 2008). Connecting with nature boosts our spirits and sharpens our minds (Zelenski & Nisbet, 2014).

“It keeps me from looking at my phone every two seconds.”

As psychologist Steven Pinker (2010) said, “The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life.”