Culture and Emotional Expression

The meaning of gestures varies with the culture. U.S. President Richard Nixon learned this after making the North American “A-OK” sign before a welcoming crowd of Brazilians, not realizing it was a crude insult in that country. The importance of cultural definitions of gestures and other body language was again demonstrated in 1968, when North Korea publicized photos of supposedly happy officers from a captured U.S. Navy spy ship. In the photo, three men had raised their middle finger, telling their captors it was a “Hawaiian good luck sign” (Fleming & Scott, 1991).

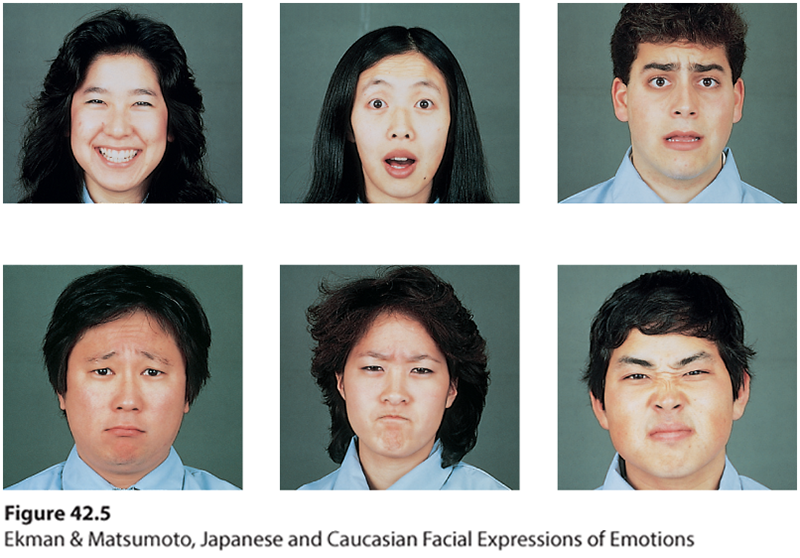

Do facial expressions also have different meanings in different cultures? To find out, two investigative teams showed photographs of various facial expressions to people in different parts of the world and asked them to guess the emotion (Ekman, 1994, 2016; Izard, 1977, 1994). You can try this matching task yourself by pairing the six emotions with the six faces in Figure 42.5.

Figure 42.5 Culture-specific or culturally universal expressions?

As people of differing cultures, do our faces speak differing languages? Which face expresses disgust? Anger? Fear? Happiness? Sadness? Surprise? (From Matsumoto & Ekman, 1989.)1

Regardless of your cultural background, you probably did pretty well. A smile’s a smile the world around. Ditto for sadness. Other emotional expressions are less universally recognized (Crivelli et al., 2016a; Jack et al., 2012). But there is no culture where people frown when they are happy.

Facial expressions do convey some nonverbal accents that provide clues to one’s culture (Crivelli et al., 2016b; Marsh et al., 2003). Thus, data from 182 studies have shown slightly enhanced accuracy when people judged emotions from their own culture (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Laukka et al., 2016). Still, the telltale signs of emotion generally cross cultures. The world over, children cry when distressed, shake their heads when defiant, and smile when they are happy. So, too, with blind children who have never seen a face (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1971). People blind from birth spontaneously exhibit the common facial expressions associated with such emotions as joy, sadness, fear, and anger (Galati et al., 1997).

Do these shared emotional categories reflect shared cultural experiences, such as movies and TV broadcasts seen around the world? Apparently not. Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen (1971) asked isolated people in New Guinea to respond to such statements as, “Pretend your child has died.” When North American college and university students viewed the recorded responses, they easily read the New Guineans’ facial reactions.

“ For news of the heart, ask the face.”

Guinean proverb

So we can say that facial muscles speak a universal language. This discovery would not have surprised Charles Darwin (1809–1882), who argued that in prehistoric times, before our ancestors communicated in words, they communicated threats, greetings, and submission with facial expressions. Their shared expressions helped them survive (Hess & Thibault, 2009). In confrontations, for example, a human sneer retains elements of an animal baring its teeth in a snarl. Emotional expressions may enhance our survival in other ways, too. Surprise raises the eyebrows and widens the eyes, enabling us to take in more information. Disgust wrinkles the nose, closing it from foul odors.

Smiles are social as well as emotional events. Euphoric Olympic gold-medal winners typically don’t smile when they are awaiting their award ceremony. But they wear broad grins when interacting with officials and when facing the crowd and cameras (Fernández-Dols & Ruiz-Belda, 1995). Thus, a glimpse at competitors’ spontaneous expressions following Olympic and national judo competitions gives a very good clue to who won, no matter their country (Crivelli et al., 2015; Matsumoto & Willingham, 2006, 2009). Even natively blind athletes, who have never observed smiles, display social smiles in such situations (Matsumoto et al., 2009).

Universal emotions No matter where on Earth you live, you have no trouble recognizing the joy experienced by Chicago Cubs fans over their 2016 World Series victory following a 108-year wait.

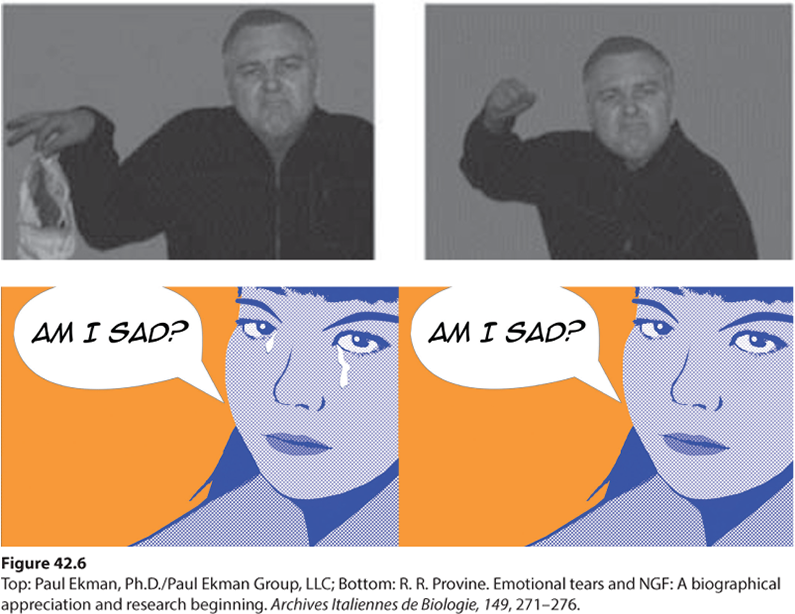

Although we share a universal facial language for some emotions, it has been adaptive for us to interpret faces in particular contexts (Figure 42.6). People judge an angry face set in a frightening situation as afraid. They judge a fearful face set in a painful situation as pained (Carroll & Russell, 1996). Movie directors harness this phenomenon by creating scenes and soundtracks that amplify our perceptions of particular emotions.

Figure 42.6 We read faces in context

Whether we perceive the man in the top row as disgusted or angry depends on which body his face appears on (Aviezer et al., 2008). In the second row, tears on a woman’s face make her expression seem sadder (Provine et al., 2009).

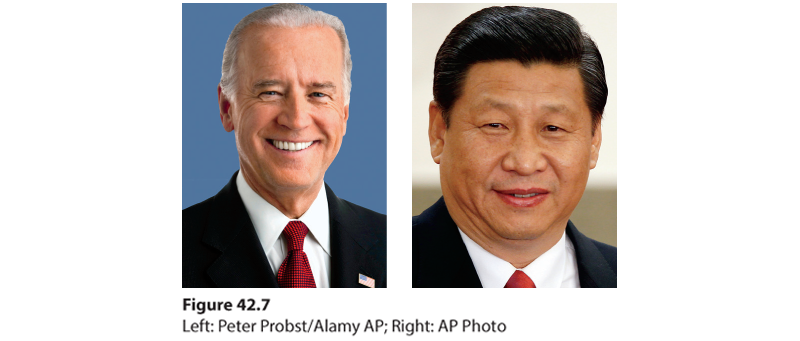

Cultures may share a facial language, but they differ in how much emotion they express. Those that encourage individuality, as in Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America, display visible emotions (van Hemert et al., 2007). Those that encourage people to adjust to others, as in Japan and China, often have less visible emotional displays (Matsumoto et al., 2009; Tsai et al., 2007). In Japan, people infer emotion more from the surrounding context. Moreover, the mouth, often so expressive in North Americans, conveys less emotion than do the telltale eyes (Masuda et al., 2008; Yuki et al., 2007). Compared with their counterparts in China, where calmness is emphasized, European-American leaders follow different display rules—they express excited smiles six times more frequently in their official photos (Figure 42.7) (Tsai et al., 2006, 2016). If we’re happy and we know it, our culture will teach us how to show it.

Figure 42.7 Culture and smiling

Former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden’s broad smile and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s more reserved one illustrate a cultural difference in facial expressiveness.

Cultural differences also exist within nations. The Irish and their Irish-American descendants have tended to be more expressive than the Scandinavians and their Scandinavian-American descendants (Tsai & Chentsova-Dutton, 2003). And that reminds us of a familiar lesson: Like most psychological events, emotion is best understood not only as a biological and cognitive phenomenon, but also as a social-cultural phenomenon.