Reducing Stress

Developing more optimistic thinking, building social support, and having a sense of personal control (Module 29) can help us experience less stress and thus improve our health. Moreover, these factors interrelate: People who have been upbeat about themselves and their future have tended also to enjoy health-promoting social ties (Stinson et al., 2008). But sometimes we cannot alleviate stress and simply need to manage our stress. Aerobic exercise, relaxation, meditation, and spiritual communities may help us gather inner strength and lessen stress effects.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise is sustained, oxygen-consuming, exertion—such as jogging, swimming, or biking—that increases heart and lung fitness. It’s hard to find bad things to say about exercise. Estimates vary, but moderate exercise adds to your quantity of life—about seven hours longer life for every exercise hour (Lee et al., 2017)—and your quality of life, with more energy, better mood, and stronger relationships (Flueckiger et al., 2016; Hogan et al., 2015).

Exercise helps fight heart disease by strengthening the heart, increasing blood flow, keeping blood vessels open, and lowering both blood pressure and the blood pressure reaction to stress (Ford, 2002; Manson, 2002). Compared with inactive adults, people who exercise suffer about half as many heart attacks (Evenson et al., 2016; Visich & Fletcher, 2009). Dietary fat contributes to clogged arteries, but exercise makes our muscles hungry for those fats and helps clean them out of our arteries (Barinaga, 1997). In one study of over 650,000 American adults, walking 150 minutes per week predicted living 7 more years (Moore et al., 2012). A follow-up study of 1.44 million Americans and Europeans found that exercise predicted “lower risks of many cancer types” (Moore et al., 2016). Regular exercise in later life also predicts better cognitive functioning and reduced risk of neurocognitive disorder and Alzheimer’s disease (Kramer & Erickson, 2007).

The genes passed down to us from our distant ancestors were those that enabled the physical activity essential to hunting, foraging, and farming (Raichlen & Polk, 2013). In muscle cells, those genes, when activated by exercise, respond by producing proteins. In the modern inactive person, these genes produce lower quantities of proteins and leave us susceptible to more than 20 chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer (Booth & Neufer, 2005). Inactivity is thus potentially toxic. Physical activity can weaken the influence of some genetic risk factors. In one analysis of 45 studies, the risk of obesity fell by 27 percent (Kilpeläinen et al., 2012).

Does exercise also boost the spirit? In a 21-country survey of university students, physical exercise was a strong and consistent predictor of life satisfaction (Grant et al., 2009). Americans, Canadians, and Britons who do aerobic exercise at least three times a week manage stress better, exhibit more self-confidence, feel more vigor, and feel less depressed and fatigued than their inactive peers (Rebar et al., 2015; Smits et al., 2011). Going from active exerciser to couch potato can increase the likelihood of depression—by 51 percent in 2 years for the women in one study (Wang, F. et al., 2011). Among people with depression, getting off the couch and into a more physically active life reduces depressive symptoms (Kvam et al., 2016; Snippe et al., 2016). “Exercise has a large and significant antidepressant effect,” concluded one digest of 25 controlled studies (Schuch et al., 2016).

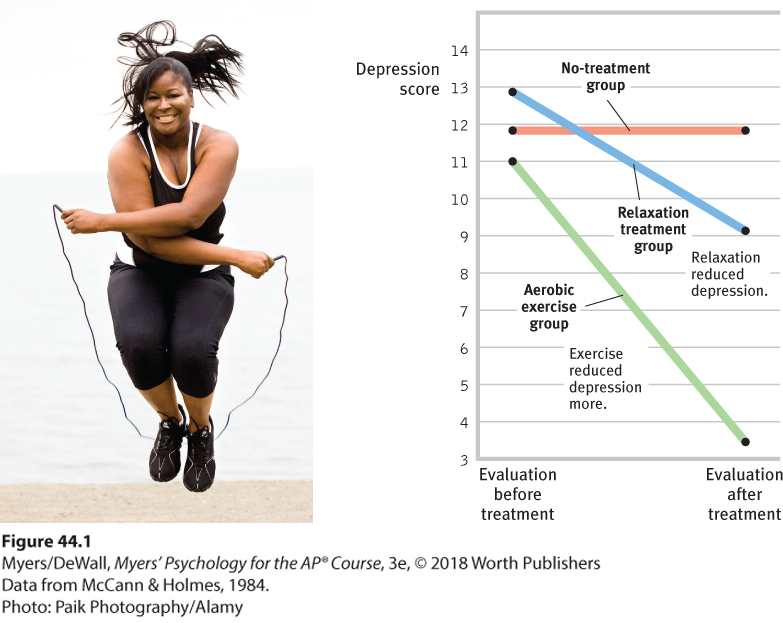

But we could state this observation another way: Stressed and depressed people exercise less. These findings are correlations, and cause and effect are unclear. To sort out cause and effect, researchers experiment. They randomly assign stressed, depressed, or anxious people either to an aerobic exercise group or to a control group. Next, they measure whether aerobic exercise (compared with a control activity not involving exercise) produces a change in stress, depression, anxiety, or some other health-related outcome. One classic experiment randomly assigned mildly depressed female college students to three groups. One-third participated in a program of aerobic exercise. Another third took part in a program of relaxation exercises. The remaining third (the control group) formed a no-treatment group (McCann & Holmes, 1984). As Figure 44.1 shows, 10 weeks later, the women in the aerobic exercise program reported the greatest decrease in depression. Many had, quite literally, run away from their troubles.

Figure 44.1 Aerobic exercise reduces mild depression

Dozens of other experiments and longitudinal studies confirm that exercise prevents or reduces depression and anxiety (Catalan-Matamoros et al., 2016; Conn, 2010; Pinto Pereira et al., 2014). When experimenters randomly assigned depressed people to an exercise group, an antidepressant group, or a placebo pill group, exercise diminished depression as effectively as antidepressants—and with longer-lasting effects (Hoffman et al., 2011).

Vigorous exercise provides a substantial and immediate mood boost (Watson, 2000). Even a 10-minute walk stimulates 2 hours of increased well-being by raising energy levels and lowering tension (Thayer, 1987, 1993). Exercise works its magic in several ways. It increases arousal, thus counteracting depression’s low arousal state. It enables muscle relaxation and sounder sleep. Like an antidepressant drug, it orders up mood-boosting chemicals from our body’s internal pharmacy—neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and the endorphins (Jacobs, 1994; Salmon, 2001). What is more, toned muscles filter out depression-causing toxins (Agudelo et al., 2014). Exercise also fosters neurogenesis. In mice, exercise causes the brain to produce a molecule that stimulates the production of new, stress-resistant neurons (Hunsberger et al., 2007; Reynolds, 2009; van Praag, 2009).

The mood boost When energy or spirits are sagging, few things reboot the day better than exercising, as I [DM] can confirm from my noontime biking and basketball, and as I [ND] can confirm from my running.

On a simpler level, the sense of accomplishment and improved physique and body image that often accompany a successful exercise routine may enhance one’s self-image, leading to a better emotional state. Frequent exercise is like a drug that prevents and treats disease, increases energy, calms anxiety, and boosts mood—a drug we would all take, if available. Yet few people (only 1 in 4 in the United States) do it (Mendes, 2010).

Relaxation and Meditation

Knowing the damaging effects of stress, could we learn to counteract our stress responses by altering our thinking and lifestyle? As we learned in Module 28, in the late 1960s, psychologists began experimenting with biofeedback, a system of recording, amplifying, and feeding back information about subtle physiological responses, many controlled by the autonomic nervous system. However, a decade of study revealed only limited effectiveness, with biofeedback working best on tension headaches (Miller, 1985; NIH, 1995).

Simple methods of relaxation, which require no expensive equipment, produce many of the results biofeedback once promised. Figure 44.1 pointed out that aerobic exercise reduces depression. But did you notice in that figure that depression also decreased among women in the relaxation treatment group? More than 60 studies have found that relaxation procedures can also help alleviate headaches, hypertension, anxiety, and insomnia (Nestoriuc et al., 2008; Stetter & Kupper, 2002).

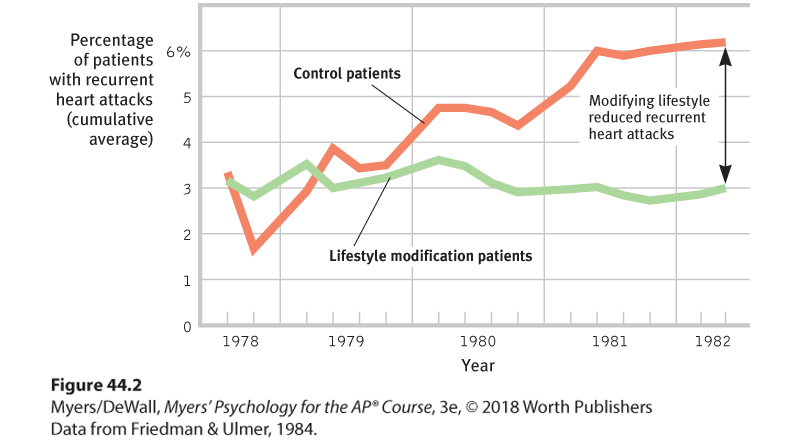

Such findings would not surprise Meyer Friedman, Ray Rosenman, and their colleagues. They tested relaxation in a program designed to help Type A heart attack survivors (who are more prone to heart attacks than their Type B peers) reduce their risk of future attacks. They randomly assigned hundreds of middle-aged men to one of two groups. The first group received standard advice from cardiologists about medications, diet, and exercise habits. The second group received similar advice, but they also were taught ways of modifying their lifestyles. They learned to slow down and relax by walking, talking, and eating more slowly. They learned to smile at others and laugh at themselves. They learned to admit their mistakes, to take time to enjoy life, and to renew their religious faith. The training paid off (Figure 44.2). During the next 3 years, those who learned to modify their lifestyle had half as many repeat heart attacks as did the first group. This, wrote the exuberant Friedman, was an unprecedented, spectacular reduction in heart attack recurrence. A smaller-scale British study spanning 13 years similarly showed a halved death rate among high-risk people trained to alter their thinking and lifestyle (Eysenck & Grossarth-Maticek, 1991). After suffering a heart attack at age 55, Friedman started taking his own behavioral medicine—and lived to age 90 (Wargo, 2007).

Figure 44.2 Recurrent heart attacks and lifestyle modification

The San Francisco Recurrent Coronary Prevention Project offered counseling from a cardiologist to survivors of heart attacks. Those who were also guided in modifying their Type A lifestyle suffered fewer repeat heart attacks.

Time may heal all wounds, but relaxation can help speed that process. In one study, surgery patients were randomly assigned to two groups. Both groups received standard treatment, but the second group also experienced a 45-minute relaxation exercise and received relaxation recordings to use before and after surgery. A week after surgery, patients in the relaxation group reported lower stress and showed better wound healing (Broadbent et al., 2012).

Meditation is a modern practice with a long history. In many world religions, meditation has been used to reduce suffering and improve awareness, insight, and compassion. Numerous studies have confirmed the psychological benefits of different types of meditation (Goyal et al., 2014; Rosenberg et al., 2015; Sedlmeier et al., 2012). These types include mindfulness meditation, which today has found a new home in stress management programs. If you were taught this practice, you would relax and silently attend to your inner state, without judging it (Brown et al., 2016; Kabat-Zinn, 2001). You would sit down, close your eyes, and mentally scan your body from head to toe. Zooming in on certain body parts and responses, you would remain aware and accepting. You would also pay attention to your breathing, attending to each breath as if it were a material object.

Practicing mindfulness may lessen anxiety and depression (Goyal et al., 2014). In one study of 1140 people, some received mindfulness-based therapy for several weeks. Others did not. Levels of anxiety and depression were lower among those who received the therapy (Hofmann et al., 2010). Mindfulness practices have also been linked with improved sleep, interpersonal relationships, and immune system functioning (Gong et al., 2016; Rosenkranz et al., 2013; Sedlmeier et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2007). Just a few minutes of daily mindfulness meditation is enough to improve concentration and decision making (Hafenbrack et al., 2014; Rahl et al., 2016).

“ Sit down alone and in silence. Lower your head, shut your eyes, breathe out gently, and imagine yourself looking into your own heart. . . . As you breathe out, say ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.’ . . . Try to put all other thoughts aside. Be calm, be patient, and repeat the process very frequently.”

Gregory of Sinai, died 1346

So, what’s going on in the brain as we practice mindfulness? Correlational and experimental studies offer three explanations. Mindfulness

- STRENGTHENS CONNECTIONS AMONG BRAIN REGIONS. The affected regions are those associated with focusing our attention, processing what we see and hear, and being reflective and aware (Berkovich-Ohana et al., 2014; Ives-Deliperi et al., 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 2011).

- ACTIVATES BRAIN REGIONS ASSOCIATED WITH MORE REFLECTIVE AWARENESS. (Davidson et al., 2003; Way et al., 2010). When labeling emotions, mindful people show less activation in the amygdala (a fear-associated brain region) and more activation in the prefrontal cortex, which aids emotion regulation (Creswell et al., 2007; Gotink et al., 2016).

- CALMS BRAIN ACTIVATION IN EMOTIONAL SITUATIONS. This lower activation was clear in one study in which participants watched two movies—one sad, one neutral. Those in the control group, who were not trained in mindfulness, showed strong differences in brain activation when watching the two movies. Those who had received mindfulness training showed little change in brain response to the two movies (Farb et al., 2010). Emotionally unpleasant images also trigger weaker electrical brain responses in mindful people than in their less mindful counterparts (Brown et al., 2013). A mindful brain is strong, reflective, and calm.

Exercise and meditation are not the only routes to healthy relaxation. Massage helps relax both premature infants and those suffering pain, and it relaxes muscles and helps reduce depression (Hou et al., 2010).

Faith Communities and Health

Religiously active people tend to live longer than those who are not religiously active, a curious correlation called the faith factor (Koenig et al., 2012). One study compared the death rates for 3900 people living in two Israeli communities. The first community contained 11 religiously orthodox collective settlements; the second contained 11 matched, nonreligious collective settlements (Kark et al., 1996). Over a 16-year period, “belonging to a religious collective was associated with a strong protective effect” not explained by age or economic differences. In every age group, religious community members were about half as likely to have died as were their nonreligious counterparts. This difference is roughly comparable to the gender difference in mortality. A more recent study followed 74,534 nurses over 20 years. When controlling for various health risk factors, those who attended religious services more than weekly were a third less likely to have died than were nonattenders (Li et al., 2016).

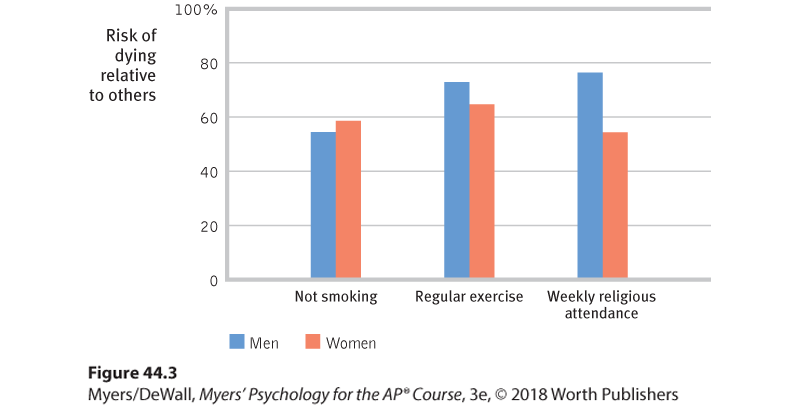

How should we interpret such findings? Correlations are not cause-effect statements, and they leave many factors uncontrolled (Sloan, 2005; Sloan et al., 1999, 2000, 2002). Here is another possible interpretation: Women are more religiously active than men, and women outlive men. Might religious involvement merely reflect this gender-longevity link? Apparently not. One 8-year National Institutes of Health study followed 92,395 women, ages 50 to 79. After controlling for many factors, researchers found that women attending religious services at least weekly experienced an approximately 20 percent reduced risk of death during the study period (Schnall et al., 2010). Moreover, the association between religious involvement and life expectancy is also found among men (Benjamins et al., 2010; McCullough et al., 2000; McCullough & Laurenceau, 2005). A 28-year study that followed 5286 Californians found that, after controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, and education, frequent religious attenders were 36 percent less likely to have died in any year (Figure 44.3). In another 8-year controlled study of more than 20,000 people (Hummer et al., 1999), this effect translated into a life expectancy of 83 years for those frequently attending religious services and only 75 years for nonattenders.

Figure 44.3 Predictors of longer life: Not smoking, frequent exercise, and regular religious attendance

One 28-year study followed 5286 Alameda, California, adults (Oman et al., 2002; Strawbridge, 1999; Strawbridge et al., 1997). Controlling for age and education, the researchers found that not smoking, regular exercise, and religious attendance all predicted a lowered risk of death in any given year. Women attending weekly religious services, for example, were only 54 percent as likely to die in a typical study year as were nonattenders.

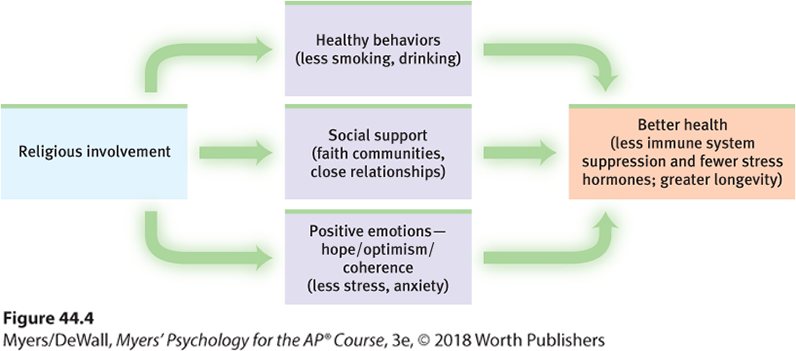

These correlational findings do not indicate that nonattenders can suddenly add 8 years of life if they start attending services and change nothing else. Nevertheless, the findings do indicate that religious involvement, like nonsmoking and exercise, is a predictor of health and longevity. Research points to three possible explanations for the religiosity-longevity correlation (Figure 44.4):

- HEALTHY BEHAVIORS. Religion promotes self-control (DeWall et al., 2014; McCullough & Willoughby, 2009). And that helps explain why religiously active people tend to smoke and drink much less and to have healthier lifestyles (Islam & Johnson, 2003; Koenig & Vaillant, 2009; Masters & Hooker, 2013). In one Gallup survey of 550,000 Americans, 15 percent of the very religious were smokers, as were 28 percent of the nonreligious (Newport et al., 2010). But such lifestyle differences are not great enough to explain the dramatically reduced mortality in the Israeli religious settlements. In American studies, too, about 75 percent of the longevity difference remained when researchers controlled for unhealthy behaviors, such as inactivity and smoking (Musick et al., 1999).

- SOCIAL SUPPORT. Could social support explain the faith factor (Ai et al., 2007; Kim-Yeary et al., 2012)? Faith is often a communal experience. To belong to a faith community is to participate in a support network. Religiously active people are there for one another when misfortune strikes. Moreover, religion encourages marriage, another predictor of health and longevity. In the 20-year nurses study, social support was the biggest contributor to the religiosity factor—explaining a fourth of its effect.

- POSITIVE EMOTIONS. Even after controlling for social support, gender, unhealthy behaviors, and preexisting health problems, the mortality studies have found that religiously engaged people tend to live longer (Chida et al., 2009). Researchers speculate that religiously active people may benefit from a stable, coherent worldview, a sense of hope for the long-term future, feelings of ultimate acceptance, and the relaxed meditation of prayer or other religious observance. These intervening variables may also help to explain why the religiously active have had healthier immune functioning, fewer hospital admissions, and, for people with AIDS, fewer stress hormones and longer survival (Ironson et al., 2002; Koenig & Larson, 1998; Lutgendorf et al., 2004).

Figure 44.4 Possible explanations for the correlation between religious involvement and health/longevity