Developmental Psychology’s Major Issues

Researchers find human development interesting for the same reasons most of the rest of us do—they want to understand more about how we’ve become our current selves, and how we may change in the years ahead. Developmental psychology examines our physical, cognitive, and social development across the life span, with a focus on three major issues:

- Nature and nurture: How does our genetic inheritance (our nature) interact with our experiences (our nurture) to influence our development?

- Continuity and stages: What parts of development are gradual and continuous, like riding an escalator? What parts change abruptly in separate stages, like climbing rungs on a ladder?

- Stability and change: Which of our traits persist through life? How do we change as we age?

Nature and Nurture

The gene combination created by the merging of our mother’s egg with our father’s sperm helped form us as individuals. Genes predispose both our shared humanity and our individual differences.

But our experiences also form us, in the womb and in the world. Even differences rooted in our nature may be strengthened by our nurture. We are not formed by either nature or nurture, but by their interrelationships—their interaction. Biological, psychological, and social-cultural forces interact.

Mindful of how others differ from us, however, we often fail to notice the similarities stemming from our shared biology. Regardless of our culture, we humans share the same life cycle. We speak to our infants in similar ways and respond similarly to their coos and cries (Bornstein et al., 1992a,b). All over the world, the children of warm and supportive parents feel better about themselves and are less hostile than are the children of punishing and rejecting parents (Rohner, 1986; Scott et al., 1991). Although ethnic groups differ in school achievement and delinquency, the differences are “no more than skin deep.” To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well. Compared with the person-to-person differences within groups, the differences between groups are small.

“ Nature is all that a man brings with him into the world; nurture is every influence that affects him after his birth.”

Francis Galton, English Men of Science, 1874

Continuity and Stages

Do adults differ from infants as a giant redwood differs from its seedling—a difference created by gradual, cumulative growth? Or do they differ as a butterfly differs from a caterpillar—a difference of distinct stages?

Researchers who emphasize experience and learning typically see development as a slow, continuous shaping process. Those who emphasize biological maturation tend to see development as a sequence of genetically predisposed stages or steps: Although progress through the various stages may be quick or slow, everyone passes through the stages in the same order.

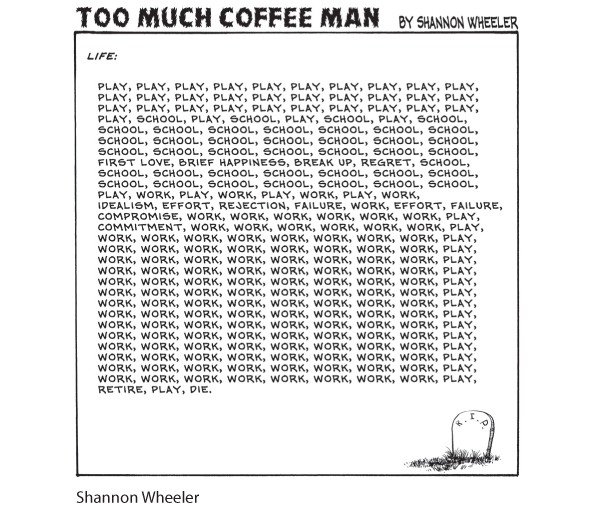

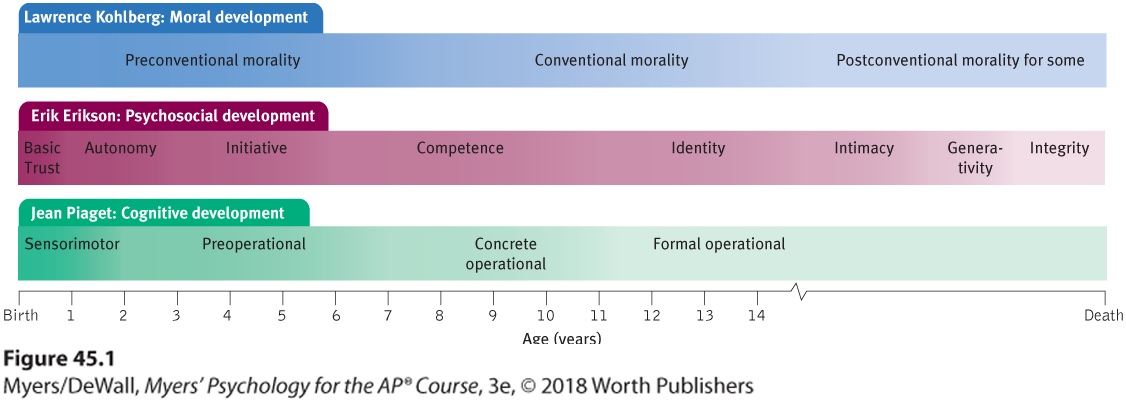

Stages of the life cycle

Are there clear-cut stages of psychological development, as there are physical stages such as walking before running? The stage theories we will consider—of Jean Piaget on cognitive development, Lawrence Kohlberg on moral development, and Erik Erikson on psychosocial development—propose developmental stages (summarized in Figure 45.1). But as we will also see, some research casts doubt on the idea that life proceeds through neatly defined age-linked stages.

Figure 45.1 Comparing the stage theories

(With thanks to Dr. Sandra Gibbs, Muskegon Community College, for inspiring this illustration.)

Although many modern developmental psychologists do not identify as stage theorists, the stage concept remains useful. The human brain does experience growth spurts during childhood and puberty that correspond roughly to Piaget’s stages (Thatcher et al., 1987). And stage theories contribute a developmental perspective on the whole life span, by suggesting how people of one age think and act differently when they arrive at a later age.

Stability and Change

As we follow lives through time, do we find more evidence for stability or change? If reunited with a long-lost grade-school friend, do we instantly realize that “it’s the same old Andy”? Or do people we once befriended seem like strangers? (At least one acquaintance of mine [DM’s] would choose the second option. At his 40-year college reunion, he failed to recognize a former classmate. The understandably appalled classmate was his long-ago first wife!)

We experience both stability and change. Some of our characteristics, such as temperament, are very stable:

- One research team that studied 1000 people from ages 3 to 38 was struck by the consistency of temperament and emotionality across time (Moffitt et al., 2013; Slutske et al., 2012). Out-of-control 3-year-olds were the most likely to become teen smokers, adult criminals, or out-of-control gamblers. In another study, 6-year-old Canadian boys with conduct problems were four times more likely than other boys to be convicted of a violent crime by age 24 (Hodgins et al., 2013).

- Another research team showed that extraversion among British 16-year-olds predicted their future happiness as 60-year-olds (Gale et al., 2013). And the widest smilers in childhood and college photos are, years later, the ones most likely to enjoy enduring marriages (Hertenstein et al., 2009).

- A 40-year study found that responsible primary school children even outlive their out-of-control classmates (Spengler et al., 2016).

“ When I look at myself in the first grade and I look at myself now, I’m basically the same. The temperament is not that different.”

Donald J. Trump to his biographer, in Never Enough, 2015

“As at 7, so at 70,” says a Jewish proverb. People predict that they will not change much in the future (Quoidbach et al., 2013). In some ways, they are right. As people grow older, personality gradually stabilizes (Briley & Tucker-Drob, 2014; Specht et al., 2014).

Smiles predict marital stability In one longitudinal study of 306 college alums, 1 in 4 with yearbook expressions like the one on the left later divorced, as did only 1 in 20 with smiles like the one on the right (Hertenstein et al., 2009).

We cannot, however, predict all aspects of our future selves based on our early life. Our social attitudes, for example, are much less stable than our temperament, especially during the impressionable late adolescent years (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989; Rekker et al., 2015). Older children and adolescents learn new ways of coping. Although delinquent children have elevated rates of later problems, many confused and troubled children blossom into mature, successful adults (Moffitt et al., 2002; Roberts, et al., 2013; Thomas & Chess, 1986). Life is a process of becoming. Our present struggles may lay the foundation for a happier tomorrow.

In some ways, we all change with age. Most shy, fearful toddlers begin opening up by age 4, and most people become more conscientious, stable, agreeable, and self-confident in the years after adolescence (Lucas & Donnellan, 2009; Shaw et al., 2010; Van den Akker et al., 2014). Risk-prone adolescents tend to become more cautious adults (Mata et al., 2016). Indeed, many irresponsible 16-year-olds have matured into 40-year-old business or cultural leaders. (If you are the former, you aren’t done yet.) Such changes can occur without changing a person’s position relative to others of the same age. The hard-driving young adult may mellow by later life, yet still be a relatively driven senior citizen.

As adults grow older, there is continuity of self.

Life requires both stability and change. Stability provides our identity, enabling us to depend on others and on ourselves. Our potential for change gives us our hope for a brighter future, allowing us to adapt and grow with experience.