Piaget’s Theory and Current Thinking

Piaget believed that children construct their understanding of the world while interacting with it. Their minds experience spurts of change, followed by greater stability as they move from one cognitive plateau to the next, each with distinctive characteristics that permit specific kinds of thinking. In Piaget’s view, cognitive development consisted of four major stages—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

Sensorimotor Stage

In the sensorimotor stage, from birth to nearly age 2, babies take in the world through their senses and actions—through looking, hearing, touching, mouthing, and grasping. As their hands and limbs begin to move, they learn to make things happen.

Very young babies seem to live in the present: Out of sight is out of mind. In one test, Piaget showed an infant an appealing toy and then flopped his beret over it. Before the age of 6 months, the infant acted as if the toy ceased to exist. Young infants lack object permanence—the awareness that objects continue to exist even when not perceived. By 8 months, infants begin exhibiting memory for things no longer seen. If you hide a toy, the infant will momentarily look for it (Figure 47.3). Within another month or two, the infant will look for it even after being restrained for several seconds.

Figure 47.3 Object permanence

Infants younger than 6 months seldom understand that things continue to exist when they are out of sight. But for this older infant, out of sight is definitely not out of mind.

So does object permanence in fact blossom suddenly at 8 months, much as tulips blossom in spring? Today’s researchers believe object permanence unfolds gradually, and they see development as more continuous than Piaget did. Even young infants will at least momentarily look for a toy where they saw it hidden a second before (Wang et al., 2004).

Researchers also believe Piaget and his followers underestimated young children’s competence. Young children think like little scientists. They test ideas, make causal inferences, and learn from statistical patterns (Gopnik et al., 2015). Consider these simple experiments:

- Baby physics: Like adults staring in disbelief at a magic trick (the “Whoa!” look), infants look longer at and explore impossible scenes—a car seeming to pass through a solid object, a ball stopping in midair, or an object violating object permanence by magically disappearing (Baillargeon, 2008; Shuwairi & Johnson, 2013; Stahl & Feigenson, 2015). Why do infants show this visual bias? Because impossible events violate infants’ expectations (Baillargeon et al., 2016).

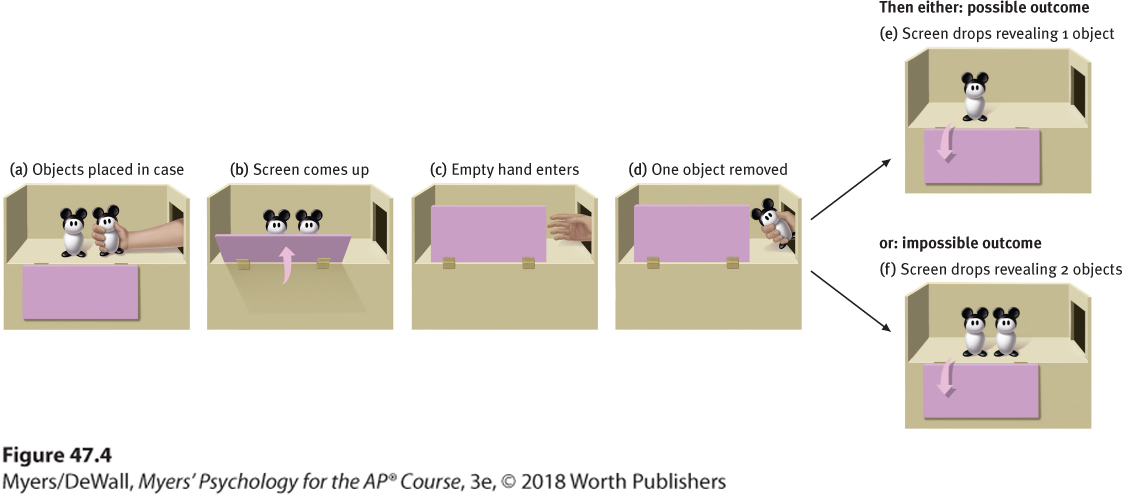

- Baby math: Karen Wynn (1992, 2000, 2008) showed 5-month-olds one or two objects (Figure 47.4). Then she hid the objects behind a screen, and visibly removed or added one (Figure 47.4d). When she lifted the screen, the infants sometimes did a double take, staring longer when shown a wrong number of objects (Figure 47.4f). But were they just responding to a greater or smaller mass of objects, rather than a change in number (Feigenson et al., 2002)? Later experiments showed that babies’ number sense extends to larger numbers, to ratios, and to such things as drumbeats and motions (Libertus & Brannon, 2009; McCrink & Wynn, 2004; Spelke et al., 2013). If accustomed to a Daffy Duck puppet jumping three times on stage, they showed surprise if it jumped only twice.

Figure 47.4 Baby math

Shown a numerically impossible outcome, 5-month-old infants stare longer (Wynn, 1992).

Clearly, infants are smarter than Piaget appreciated. Even as babies, we had a lot on our minds.

Preoperational Stage

Piaget believed that until about age 6 or 7, children are in a preoperational stage—able to represent things with words and images but too young to perform mental operations (such as imagining an action and mentally reversing it). For a 5-year-old, the milk that seems “too much” in a tall, narrow glass may become just right if poured into a short, wide glass. Focusing only on the height dimension, this child cannot perform the operation of mentally pouring the milk back. Before about age 6, said Piaget, children lack the concept of conservation—the principle that quantity remains the same despite changes in shape (Figure 47.5).

Figure 47.5 Piaget’s test of conservation

This visually focused preoperational child does not yet understand the principle of conservation. When the milk is poured into a tall, narrow glass, it suddenly seems like “more” than when it was in the shorter, wider glass. In another year or so, she will understand that the amount stays the same.

Pretend Play

Symbolic thinking and pretend play appear at an earlier age than Piaget supposed. Judy DeLoache (1987) discovered this when she showed children a model of a room and hid a miniature stuffed dog behind its miniature couch. The 2½-year-olds easily remembered where to find the miniature toy, but they could not use the model to locate an actual stuffed dog behind a couch in a real room. Three-year-olds—only 6 months older—usually went right to the actual stuffed animal in the real room, showing they could think of the model as a symbol for the room. Although Piaget did not view the stage transitions as abrupt, he probably would have been surprised to see symbolic thinking at such an early age.

Egocentrism

Piaget taught us that preschool children are egocentric: They have difficulty perceiving things from another’s point of view. They are like the person who, when asked by someone across a river, “How do I get to the other side?” answered, “You are on the other side.” Asked to “show Mommy your picture,” 2-year-old Gabriella holds the picture up facing her own eyes. Three-year-old Gray makes himself “invisible” by putting his hands over his eyes, assuming that if he can’t see his grandparents, they can’t see him. Children’s conversations also reveal their egocentrism, as one young boy demonstrated (Phillips, 1969, p. 61):

“Do you have a brother?”

“Yes.”

“What’s his name?”

“Jim.”

“Does Jim have a brother?”

“No.”

Egocentrism in action “Look, Granddaddy, a match!” So said my [DM’s] granddaughter, Allie, at age 4, when showing me two memory game cards with matching pictures—that faced her.

Like Gabriella, TV-watching preschoolers who block your view of the TV assume that you see what they see. They simply have not yet developed the ability to take another’s viewpoint. Even teens and adults may overestimate the extent to which others share our opinions, knowledge, and perspectives. We assume that something will be clear to others if it is clear to us, or that e-mail recipients will “hear” our “just kidding” intent (Epley et al., 2004; Kruger et al., 2005). Perhaps you can recall asking someone to guess a simple tune such as “Happy Birthday” as you clapped or tapped it out. With the tune in your head, it seemed so obvious! But you suffered the egocentric curse of knowledge, assuming that what was in your head was also in someone else’s.

Theory of Mind

When Little Red Riding Hood realized her “grandmother” was really a wolf, she swiftly revised her ideas about the creature’s intentions and raced away. Preschoolers, although still egocentric, develop this ability to infer others’ mental states when they begin forming a theory of mind (Premack & Woodruff, 1978).

Infants as young as 7 months show some knowledge of others’ minds (Kovács et al., 2010). With time, the ability to take another’s perspective develops. They come to understand what made a playmate angry, when a sibling will share, and what might make a parent buy a toy. They begin to tease, empathize, and persuade. And when making decisions, they use their understanding of how their actions will make others feel (Repacholi et al., 2016). Children who have an advanced ability to understand others’ minds tend to be helpful and well-liked (Imuta et al., 2016; Slaughter et al., 2015).

Between about ages 3 and 4½, children come to realize that others may hold false beliefs (Callaghan et al., 2005; Rubio-Fernández & Geurtz, 2013; Sabbagh et al., 2006). Researchers showed Canadian children a Band-Aid box and asked them what was inside (Jenkins & Astington, 1996). Expecting Band-Aids, the children were surprised to discover that the box actually contained pencils. Asked what a child who had never seen the box would think was inside, 3-year-olds typically answered “pencils.” By age 4 to 5, the children’s theory of mind had leapt forward, and they anticipated their friends’ false belief that the box would hold Band-Aids.

In a follow-up experiment, children viewed a doll named Sally leaving her ball in a red cupboard (Figure 47.6). Another doll, Anne, then moved the ball to a blue cupboard. Researchers then posed a question: When Sally returns, where will she look for the ball? Children with autism spectrum disorder had difficulty understanding that Sally’s state of mind differed from their own—that Sally, not knowing the ball had been moved, would return to the red cupboard. They also have difficulty reflecting on their own mental states. They are, for example, less likely to use the personal pronouns I and me. Deaf children with hearing parents and minimal communication opportunities have had similar difficulty inferring others’ states of mind (Peterson & Siegal, 1999).

Figure 47.6 Testing children’s theory of mind

This simple problem illustrates how researchers explore children’s presumptions about others’ mental states. (Inspired by Baron-Cohen et al., 1985.)

Concrete Operational Stage

By about age 7, said Piaget, children enter the concrete operational stage. Given concrete (physical) materials, they begin to grasp operations such as conservation. Understanding that change in form does not mean change in quantity, they can mentally pour milk back and forth between glasses of different shapes. They also enjoy jokes that use this new understanding:

Mr. Jones went into a restaurant and ordered a whole pizza for his dinner. When the waiter asked if he wanted it cut into 6 or 8 pieces, Mr. Jones said, “Oh, you’d better make it 6, I could never eat 8 pieces!” (McGhee, 1976)

Piaget believed that during the concrete operational stage, children become able to comprehend mathematical transformations and conservation. When my [DM’s] daughter, Laura, was 6, I was astonished at her inability to reverse simple arithmetic. Asked, “What is 8 plus 4?” she required 5 seconds to compute “12,” and another 5 seconds to then compute 12 minus 4. By age 8, she could answer a reversed question instantly.

Formal Operational Stage

By age 12, our reasoning expands from the purely concrete (involving actual experience) to encompass abstract thinking (involving imagined realities and symbols). As children approach adolescence, said Piaget, they can ponder hypothetical propositions and deduce consequences: If this, then that. Systematic reasoning, what Piaget called formal operational thinking, is now within their grasp.

Although full-blown logic and reasoning await adolescence, the rudiments of formal operational thinking begin earlier than Piaget realized. Consider this simple problem:

If John is in school, then Mary is in school. John is in school. What can you say about Mary?

Pretend play

Formal operational thinkers have no trouble answering correctly. But neither do most 7-year-olds (Suppes, 1982). Table 47.1 summarizes the four stages in Piaget’s theory.

| Typical Age Range | Stage and Description | Key Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to nearly 2 years | Sensorimotor Experiencing the world through senses and actions (looking, hearing, touching, mouthing, and grasping) |

|

| About 2 to 6 or 7 years | Preoperational Representing things with words and images; using intuitive rather than logical reasoning |

|

| About 7 to 11 years | Concrete operational Thinking logically about concrete events; grasping concrete analogies and performing arithmetical operations |

|

| About 12 through adulthood | Formal operational Reasoning abstractly |

|