Attachment Differences: Temperament and Parenting

What accounts for children’s attachment differences? To answer this question, Mary Ainsworth (1979) designed the strange situation experiment. She observed mother-infant pairs at home during their first six months. Later she observed the 1-year-old infants in a strange situation (usually a laboratory playroom) with and without their mothers. Such research has shown that about 60 percent of infants and young children display secure attachment (Moulin et al., 2014). In their mother’s presence they play comfortably, happily exploring their new environment. When she leaves, they become distressed; when she returns, they seek contact with her.

Other infants show insecure attachment, marked either by anxiety or by avoidance of trusting relationships. These infants are less likely to explore their surroundings; they may even cling to their mother. When she leaves, they either cry loudly and remain upset or seem indifferent to her departure and return (Ainsworth, 1973, 1989; Kagan, 1995; van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, 1988).

Ainsworth and others found that sensitive, responsive mothers—those who noticed what their babies were doing and responded appropriately—had infants who exhibited secure attachment (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997). Insensitive, unresponsive mothers—mothers who attended to their babies when they felt like doing so but ignored them at other times—often had infants who were insecurely attached. The Harlows’ monkey studies, with unresponsive artificial mothers, produced even more striking effects. When put in strange situations without their artificial mothers, the deprived infants were terrified (Figure 48.2).

Figure 48.2 Social deprivation and fear

In the Harlows’ experiments, monkeys raised with inanimate surrogate mothers were overwhelmed when placed in strange situations without that source of emotional security. (Today there is greater oversight and concern for animal welfare, which would regulate this type of study.)

Although remembered by some as the researcher who tortured helpless monkeys, Harry Harlow defended his methods: “Remember, for every mistreated monkey there exist a million mistreated children,” he said, expressing the hope that his research would sensitize people to child abuse and neglect. “No one who knows Harry’s work could ever argue that babies do fine without companionship, that a caring mother doesn’t matter,” noted Harlow biographer Deborah Blum (2011, pp. 292, 307). “And since we . . . didn’t fully believe that before Harry Harlow came along, then perhaps we needed—just once—to be smacked really hard with that truth so that we could never again doubt.”

So, caring parents matter. But is attachment style the result of parenting? Or is attachment style the result of genetically influenced temperament—a person’s characteristic emotional reactivity and intensity?

As most parents will tell you after having their second child, babies differ even before gulping their first breath. Temperament is quickly apparent, and it is genetically influenced (Kandler et al., 2013; Raby et al., 2012). Identical twins, more than fraternal twins, often have similar temperaments (Fraley & Tancredy, 2012; Kandler et al., 2013). Twin and developmental studies reveal that heredity affects temperament, and temperament affects attachment style (Picardi et al., 2011; Raby et al., 2012). Shortly after birth, some babies are noticeably difficult—irritable, intense, and unpredictable. Others are easy—cheerful, relaxed, and feeding and sleeping on predictable schedules (Chess & Thomas, 1987). This helps explain why parenting correlates with children’s behavior; it’s partly because children with difficult temperaments elicit and react more to negative parenting (Slagt et al., 2016).

And temperament differences typically persist. The most emotionally reactive newborns tend also to be the most reactive 9-month-olds (Wilson & Matheny, 1986; Worobey & Blajda, 1989). Emotionally intense preschoolers tend to become relatively intense young adults (Larsen & Diener, 1987). In one study of more than 900 New Zealanders, emotionally reactive and impulsive 3-year-olds developed into somewhat more impulsive, aggressive, and crime-prone adults (Caspi et al, 2016).

The genetic effect appears in physiological differences. Anxious, inhibited infants have high and variable heart rates and a reactive nervous system. When facing new or strange situations, they become more physiologically aroused (Kagan & Snidman, 2004; Roque et al., 2012).

By neglecting such inborn differences, the parenting studies, noted Judith Harris (1998), are like “comparing foxhounds reared in kennels with poodles reared in apartments.” So to separate nature and nurture, we would need to vary parenting while controlling temperament. (Pause and think: If you were the researcher, how might you do this?)

One Dutch researcher’s solution was to randomly assign 100 temperamentally difficult 6- to 9-month-olds to either an experimental group, in which mothers received personal training in sensitive responding, or to a control group, in which they did not (van den Boom, 1994). At 12 months of age, 68 percent of the infants in the experimental group were securely attached, as were only 28 percent of the control-group infants. Other studies have confirmed that intervention programs can increase parental sensitivity and, to a lesser extent, infant attachment security (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003; Van Zeijl et al., 2006).

“Oh, he’s cute, all right, but he’s got the temperament of a car alarm.”

As these examples indicate, researchers have more often studied mother care than father care. Infants who lack a caring mother are said to suffer “maternal deprivation”; those lacking a father’s care merely experience “father absence.” This reflects a wider attitude in which “fathering a child” has meant impregnating, and “mothering” has meant nurturing. But fathers are more than just mobile sperm banks. Across nearly 100 studies worldwide, a father’s love and acceptance have been comparable with a mother’s love in predicting their offspring’s health and well-being (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001; see also Table 48.1). In one mammoth British study following 7259 children from birth to adulthood, those whose fathers were most involved in parenting (through outings, reading to them, and taking an interest in their education) tended to achieve more in school, even after controlling for other factors such as parental education and family wealth (Flouri & Buchanan, 2004). Increasing nonmarital births and the greater instability of cohabiting versus married partnerships has, however, meant more father-absent families (Hymowitz et al., 2013). In Europe and the United States, for example, children born to cohabiting parents are (compared to those with married parents) nearly twice as likely to experience their parents’ separation, which often entails diminished father care (Wilcox & DeRose, 2017).

|

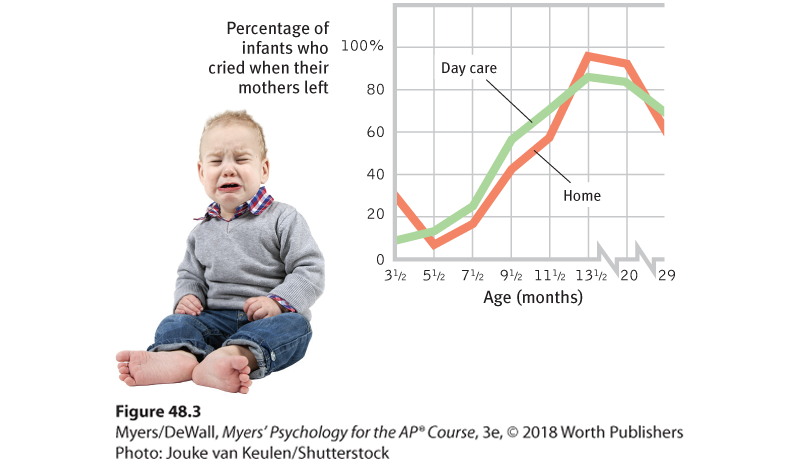

Children’s anxiety over separation from parents peaks at around 13 months, then gradually declines (Figure 48.3). This happens whether they live with one parent or two, are cared for at home or in day care, live in North America, Guatemala, or the Kalahari Desert. Does this mean our need for and love of others also fades away? Hardly. Our capacity for love grows, and our pleasure in touching and holding those we love never ceases.

Figure 48.3 Infants’ distress over separation from parents

In an experiment, infants were left by their mothers in an unfamiliar room. Regardless of whether the infant had experienced day care, the percentage who cried when the mother left peaked at about 13 months of age (Kagan, 1976).

Parenting is for dads, too Emperor penguin dads may lose half their body weight over the two months they spend keeping a precious egg warm during the harsh Antarctic winter. After mom returns from the sea, both parents take turns caring for and feeding the chick.

Full-time dad Financial analyst Walter Cranford, shown here with his baby twins, is one of a growing number of stay-at-home dads. Cranford says the experience has made him appreciate how difficult the work can be: “Sometimes at work you can just unplug, but with this you’ve got to be going all the time.”

Attachment Styles and Later Relationships

Developmental psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–1994), working with his wife, Joan Erikson (1902–1997), believed that securely attached children approach life with a sense of basic trust—a sense that the world is predictable and reliable. He attributed basic trust not to environment or inborn temperament, but to early parenting. He theorized that infants blessed with sensitive, loving caregivers form a lifelong attitude of trust rather than fear. (Later, we’ll consider Erikson’s other stages of development.)

Many researchers now believe that our early attachments form the foundation for our adult relationships and our comfort with affection and intimacy (Birnbaum et al., 2006; Fraley et al., 2013). People who report secure relationships with their parents tend to enjoy secure friendships (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012). Students leaving home to attend college or university—another kind of “strange situation”—tend to adjust well if closely attached to parents (Mattanah et al., 2011). Children with sensitive, responsive mothers tend to flourish socially and academically (Raby et al., 2014).

Feeling insecurely attached to others may take one of two main forms (Fraley et al., 2011). One is anxious attachment, in which people constantly crave acceptance but remain vigilant to signs of possible rejection. (Being sensitive to threat, anxiously attached people also tend to be skilled lie detectors and poker players [Ein-Dor & Perry, 2012, 2013].) The other is avoidant attachment, in which people experience discomfort getting close to others and use avoidant strategies to maintain distance from others. In romantic relationships, an anxious attachment style creates constant concern over rejection, leading people to cling to their partners. An avoidant style decreases commitment and increases conflict (DeWall et al., 2011; Overall et al., 2015).

“ Out of the conflict between trust and mistrust, the infant develops hope, which is the earliest form of what gradually becomes faith in adults.”

Adult attachment styles can also affect relationships with one’s own children. But say this for those (nearly half of all people) who exhibit wary, insecure attachments: Anxious or avoidant people have helped our groups detect threat and escape dangers (Ein-Dor et al., 2010).