Culture and the Self

Flip It Video: Individualist and Collectivist Cultures

Flip It Video: Individualist and Collectivist Cultures

Imagine that someone ripped away your social connections, making you a solitary refugee in a foreign land. How much of your identity would remain intact?

If you are an individualist, a great deal. You would have an independent sense of “me,” and an awareness of your unique personal convictions and values. Individualists prioritize personal goals. They define their identity mostly in terms of personal traits. They strive for personal control and individual achievement.

Individualists do share the human need to belong. They join groups. But they are less focused on group harmony and doing their duty to the group (Brewer & Chen, 2007). Being more self-contained, individualists move in and out of social groups more easily. They feel relatively free to switch places of worship, change jobs, or even leave their extended families and migrate to a new place. Marriage is often for as long as they both shall love.

If set adrift in a foreign land as a collectivist, you might experience a greater loss of identity. Cut off from family, groups, and loyal friends, you would lose the connections that have defined who you are. Group identifications provide a sense of belonging, a set of values, and an assurance of security. Collectivists have deep attachments to their groups—their family, clan, or company. Elders receive respect. For example, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly states that parents aged 60 or above can sue their sons and daughters if they fail to provide “for the elderly, taking care of them and comforting them, and cater[ing] to their special needs.”

Considerate collectivists Japan’s collectivist values, including duty to others and social harmony, were on display after the devastating 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Virtually no looting was reported, and residents remained calm and orderly, as shown here while waiting for drinking water.

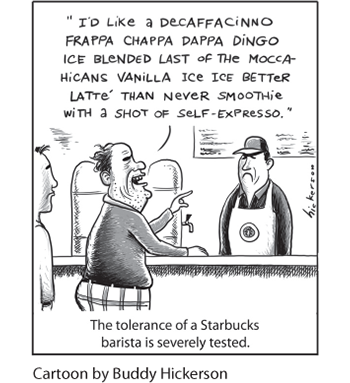

Collectivists are like athletes who take more pleasure in their team’s victory than in their own performance. They find satisfaction in advancing their groups’ interests, even at the expense of personal needs. They preserve group spirit by avoiding direct confrontation, blunt honesty, and uncomfortable topics. They value humility, not self-importance (Bond et al., 2012). Instead of dominating conversations, collectivists hold back and display shyness when meeting strangers (Cheek & Melchior, 1990). Given the priority on “we,” not “me,” that individualized North American latte—“skinny, extra hot, no-foam”—might sound selfishly demanding in Seoul (Kim & Markus, 1999).

A question: What do you think of people who willingly change their behavior to suit different people and situations? People in individualist countries (the United States and Brazil) typically describe them as “dishonest,” “untrustworthy,” and “insincere” (Levine, 2016). In traditionally collectivist countries (China, India, and Nepal), people more often describe them as “mature,” “honest,” “trustworthy,” and “sincere.”

“ One needs to cultivate the spirit of sacrificing the little me to achieve the benefits of the big me.”

Chinese saying

To be sure, there is also diversity within cultures. Within many countries, there are also distinct subcultures related to one’s religion, economic status, and region (Cohen, 2009). In China, greater collectivist thinking occurs in provinces that have produced rice, a difficult-to-grow crop that involves cooperation to sustain irrigation (Talhelm et al., 2014). In collectivist Japan, a spirit of individualism marks the “northern frontier” island of Hokkaido (Kitayama et al., 2006). And even in the most individualist countries, people have some collectivist values. But in general, people (especially men) in competitive, individualist cultures have more personal freedom, are less geographically bound to their families, enjoy more privacy, and take more pride in personal achievements (Table 59.1).

| Concept | Individualism | Collectivism |

|---|---|---|

| Self | Independent (identity from individual traits) | Interdependent (identity from belonging to groups) |

| Life task | Discover and express one’s uniqueness | Maintain connections, fit in, perform role |

| What matters | Me—personal achievement and fulfillment; rights and liberties; self-esteem | Us—group goals and solidarity; social responsibilities and relationships; family duty |

| Coping method | Change reality | Accommodate to reality |

| Morality | Defined by the individual (self-based) | Defined by social networks (duty-based) |

| Relationships | Many, often temporary or casual; confrontation acceptable | Few, close and enduring; harmony is valued |

| Attributing behavior | Behavior reflects the individual’s personality and attitudes | Behavior reflects social norms and roles |

Information from Thomas Schoeneman (1994) and Harry Triandis (1994).

Individualists even prefer unusual names, as psychologist Jean Twenge noticed while seeking a name for her first child. When she and her colleagues (2010, 2016) analyzed the first names of 358 million American babies born between 1880 and 2015, they discovered that the most common baby names had become less common. As Figure 59.1 illustrates, the percentage of boys and girls given one of the 10 most common names for their birth year has plunged. Collectivist Japan provides a contrast: Half of Japanese baby names are among the country’s 10 most common names (Ogihara et al., 2015).

Figure 59.1 A child like no other

Americans’ individualist tendencies are reflected in their choice of names for their babies. In recent years, the percentage of American babies receiving one of that year’s 10 most common names has plunged.

The individualist-collectivist divide appeared in reactions to medals received during the 2000 and 2002 Olympic games. U.S. gold medal winners and the U.S. media covering them attributed the achievements mostly to the athletes themselves (Markus et al., 2006). “I think I just stayed focused,” explained swimming gold medalist Misty Hyman. “It was time to show the world what I could do.” Japan’s gold medalist in the women’s marathon, Naoko Takahashi, had a different explanation: “Here is the best coach in the world, the best manager in the world, and all of the people who support me—all of these things . . . became a gold medal.”

Collectivist culture Although the United States is largely individualist, many cultural subgroups remain collectivist. This is true for many Alaska Natives, who demonstrate respect for tribal elders, and whose identity springs largely from their group affiliations.

Individualists demand romance and personal fulfillment in marriage (Dion & Dion, 1993). In one survey, “keeping romance alive” was rated as important to a good marriage by 78 percent of U.S. women but only 29 percent of Japanese women (American Enterprise, 1992). In China, love songs have often expressed enduring commitment and friendship (Rothbaum & Tsang, 1998): “We will be together from now on. . . . I will never change from now to forever.”

“ I used to subscribe to People. Then I switched to Us. Now I just read Self.”

Lenny, quoted by Robert Levine, Stranger in the Mirror: The Scientific Search for Self, 2016

As cultures evolve, some trends weaken and others grow stronger. Individualism and independence have been fostered by voluntary emigration, a capitalist economy, and a sparsely populated, challenging environment (Kitayama et al., 2009, 2010; Varnum et al., 2010). In Western cultures, individualism has increased strikingly over the last century, following closely on the heels of increasing affluence (Grossmann & Varnum, 2015). This trend reached a new high in 2013 and 2014, when U.S. high school and college students reported increased acceptance of diversity, but also the greatest-ever interest in obtaining benefits for themselves and the lowest-ever willingness to donate to charity (Twenge, 2016; Twenge et al., 2012).