Theories of Multiple Intelligences

Other psychologists, particularly since the mid-1980s, have sought to extend the definition of intelligence beyond the idea of academic smarts.

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

Howard Gardner has identified eight relatively independent intelligences, including the verbal and mathematical aptitudes assessed by standardized tests (Figure 60.1). Thus, the computer programmer, the poet, the street-smart adolescent, and the basketball team’s play-making point guard exhibit different kinds of intelligence (Gardner, 1998). Gardner (1999a) has also proposed a ninth possible intelligence—existential intelligence—the ability “to ponder large questions about life, death, existence.”

Figure 60.1 Gardner’s eight intelligences

Gardner has also proposed existential intelligence (the ability to ponder deep questions about life) as a ninth possible intelligence.

Gardner (1983, 2006; 2011; Davis et al., 2011) views these intelligence domains as multiple abilities that come in different packages. Brain damage, for example, may destroy one ability but leave others intact. And consider people with savant syndrome, who have an island of brilliance but often score low on intelligence tests and may have limited or no language ability (Treffert, 2010). Some can compute complicated calculations almost instantly, or identify the day of the week of any given historical date, or render incredible works of art or music (Miller, 1999).

Islands of genius: Savant syndrome After a brief helicopter ride over Singapore followed by five days of drawing, British savant artist Stephen Wiltshire accurately reproduced an aerial view of the city from memory.

About 4 in 5 people with savant syndrome are male, and many also have autism spectrum disorder (ASD; see Module 47). The late memory whiz Kim Peek (who did not have ASD) inspired the movie Rain Man. It took him 8 to 10 seconds to read and remember a page. During his lifetime, he memorized 9000 books, including Shakespeare’s works and the Bible. He could provide GPS-like travel directions within any major U.S. city. Yet he could not button his clothes, and he had little capacity for abstract concepts. Asked by his father at a restaurant to lower his voice, he slid down in his chair to lower his voice box. Asked for Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, he responded, “227 North West Front Street. But he only stayed there one night—he gave the speech the next day” (Treffert & Christensen, 2005).

Sternberg’s Three Intelligences

Robert Sternberg (1985, 2011) agrees with Gardner that there is more to success than traditional intelligence and that we have multiple intelligences. But Sternberg’s triarchic theory proposes three, not eight or nine, intelligences:

- Analytical (academic problem-solving) intelligence is assessed by intelligence tests, which present well-defined problems having a single right answer. Such tests predict school grades reasonably well and vocational success more modestly.

- Creative intelligence is demonstrated in innovative smarts: the ability to adapt to new situations and generate novel ideas.

- Practical intelligence is required for everyday tasks that may be poorly defined and may have multiple solutions.

“ You have to be careful, if you’re good at something, to make sure you don’t think you’re good at other things that you aren’t necessarily so good at. . . . Because I’ve been very successful at [software development] people come in and expect that I have wisdom about topics that I don’t.”

Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates (1998)

With support from the U.S. College Board (which administers the Advanced Placement Program® as well as the widely used SAT Reasoning Test to U.S. college and university applicants), Sternberg (2015) and his collaborators have developed new measures of creativity (such as thinking up a caption for an untitled cartoon) and practical thinking (such as figuring out how to move a large bed up a winding staircase). Compared to older measures, these more comprehensive assessments improve prediction of American students’ first-year college grades.

“You’re wise, but you lack tree smarts.”

Gardner and Sternberg differ in some areas, but they agree on two important points: Multiple abilities can contribute to life success, and differing varieties of giftedness bring both spice to life and challenges for education. Trained to appreciate such variety, many teachers have applied multiple intelligence theories in their classrooms.

Street smarts This child selling candy on the streets of Manaus, Brazil, is developing practical intelligence at a very young age.

Criticisms of Multiple Intelligence Theories

Wouldn’t it be nice if the world were so fair that a weakness in one area would be compensated by genius in another? Alas, say critics, the world is not fair (Ferguson, 2009; Scarr, 1989). Research using factor analysis confirms that there is a general intelligence factor: g matters (Johnson et al., 2008). It predicts performance on various complex tasks and in various jobs (Gottfredson, 2002a,b, 2003a,b; see also Figure 60.2). And extremely high cognitive ability scores predict exceptional achievements, such as doctoral degrees and publications (Kuncel & Hezlett, 2010).

Figure 60.2 Smart and rich?

Jay Zagorsky (2007) tracked 7403 participants in the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth across 25 years. As shown in this illustrative scatterplot, their intelligence scores correlated +.30, a moderate positive correlation, with their later income.

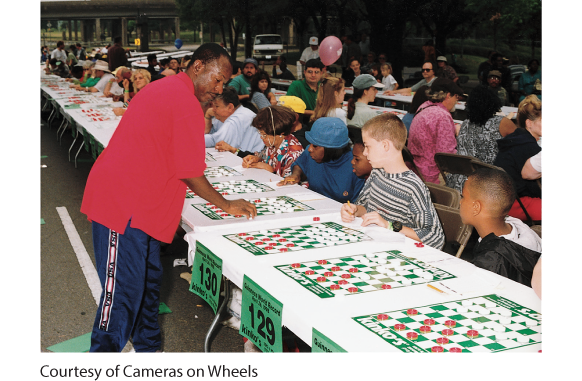

Spatial intelligence genius In 1998, World Checkers Champion Ron “Suki” King of Barbados set a new record by simultaneously playing 385 players in 3 hours and 44 minutes. Thus, while his opponents often had hours to plot their game moves, King could only devote about 35 seconds to each game. Yet he still managed to win all 385 games!

Even so, “success” is not a one-ingredient recipe. High intelligence may help you get into a good college and ultimately a desired profession, but it won’t make you successful once there. Success is a combination of talent and grit: Those who become highly successful tend also to be conscientious, well-connected, and doggedly energetic. K. Anders Ericsson and others report a 10-year rule: A common ingredient of expert performance in chess, dance, sports, computer programming, music, and medicine is “about 10 years of intense, daily practice” (Ericsson, 2007; Ericsson & Pool, 2016; Simon & Chase, 1973). Becoming a professional musician or an elite athlete requires, first, native ability (Macnamara et al., 2014, 2016). But it also requires years of practice—about 11,000 hours on average, and a minimum of 3000 hours (Campitelli & Gobet, 2011). The recipe for success is a gift of nature plus a whole lot of nurture.