Twin and Adoption Studies

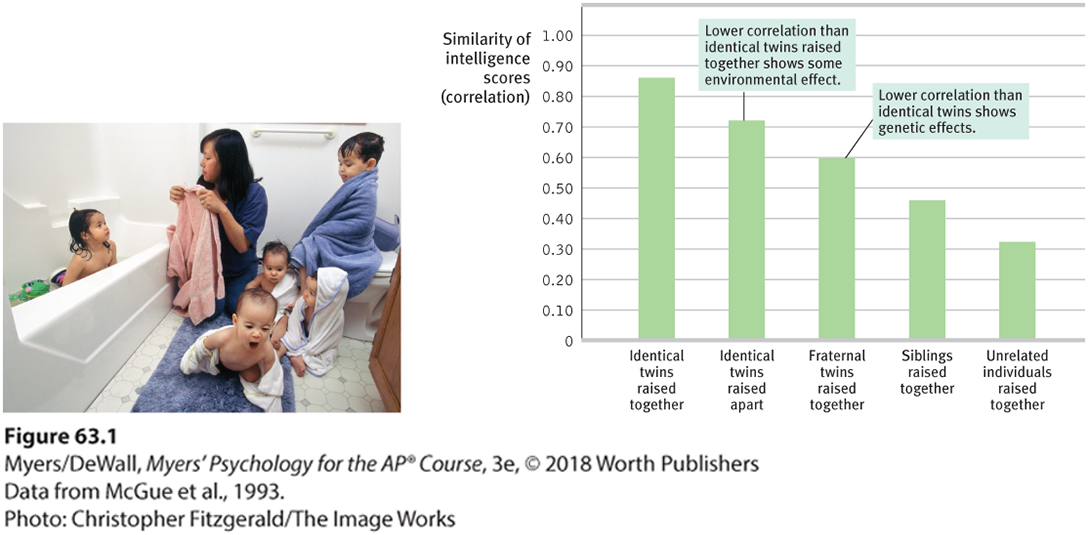

Do people who share the same genes also share mental abilities? As you can see from Figure 63.1, which summarizes many studies, the answer is clearly Yes. Consider:

- The intelligence test scores of identical twins raised together are nearly as similar as those of the same person taking the same test twice (Haworth et al., 2009; Lykken, 2006; Plomin et al., 2016). (The scores of fraternal twins, who share only about half their genes, differ more.) Estimates of the heritability of intelligence—the extent to which intelligence test score variation within a group can be attributed to genetic variation—range from 50 to 80 percent (Madison et al., 2016; Plomin et al., 2016). Identical twins also exhibit substantial similarity (and heritability) in specific talents, such as music, math, and sports. Heredity accounts for more than half the variation in the national math and science exam scores of British 16-year-olds (Shakeshaft et al., 2013; Vinkhuyzen et al., 2009).

- Scans reveal that identical twins’ brains have similar gray- and white-matter volume, and the areas associated with verbal and spatial intelligence are virtually the same (Deary et al., 2009a; Thompson et al., 2001). Their brains also show similar activity while doing mental tasks (Koten et al., 2009).

- Are there known genes for genius? When 200 researchers pooled their data on 126,559 people, all of the gene variations analyzed accounted for only about 2 percent of the differences in educational achievement (Rietveld et al., 2013, 2014). This result was not a fluke; others have replicated this modest effect of genes on educational achievement (Belsky et al., 2016). And using a new genetic method, a follow-up British study recently found genes that predicted 9 percent of the variation in school achievement at age 16 (Selzam et al., 2016). This much seems clear: Intelligence is polygenetic, involving many genes. Wendy Johnson (2010) likens the polygenetic effect to height: 54 specific gene variations together account for 5 percent of our individual height differences, leaving the rest yet to be discovered. What matters for intelligence—as for height, personality, sexual orientation, schizophrenia or just about any human trait—is the combination of many genes (Plomin et al., 2016).

Figure 63.1 Intelligence: Nature and nurture

The most genetically similar people have the most similar intelligence scores. Remember: 1.00 indicates a perfect correlation; zero indicates no correlation at all.

“I told my parents that if grades were so important they should have paid for a smarter egg donor.”

Other evidence points to environment effects:

- Where environments vary widely, as they do among children of less-educated parents, environmental differences are more predictive of intelligence scores (Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016).

- Adoption enhances the intelligence scores of mistreated or neglected children (van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2005, 2006). So does adoption from poverty into middle-class homes (Nisbett et al., 2012). In one large Swedish study, children adopted into wealthier families with more educated parents had IQ scores averaging 4.4 points higher than their not-adopted biological siblings (Kendler et al., 2015).

- The intelligence scores of “virtual twins”—same-age, unrelated siblings adopted as infants and raised together—correlate +0.28 (Segal et al., 2012). This suggests a modest influence of their shared environment.

Seeking to disentangle genes and environment, researchers have also compared the intelligence test scores of adopted children with those of (a) their biological parents (the providers of their genes) and (b) their adoptive parents (the providers of their home environment). Over time, adopted children accumulate experience in their differing adoptive families. So, would you expect the family-environment effect to grow with age and the genetic-legacy effect to shrink?

If you would, behavior geneticists have a stunning surprise for you. Mental similarities between adopted children and their adoptive families wane with age (McGue et al., 1993). Adopted children’s intelligence scores resemble those of their biological parents much more than their adoptive parents (Loehlin, 2016). Genetic influences—not environmental ones—become more apparent as we accumulate life experience. Identical twins’ similarities, for example, continue or increase into their eighties. Thus, report Ian Deary and his colleagues (2009a, 2012), the heritability of general intelligence increases from “about 30 percent” in early childhood to “well over 50 percent in adulthood.” In one massive study of 11,000 twin pairs in four countries, the heritability of general intelligence (g) increased from 41 percent in middle childhood to 55 percent in adolescence to 66 percent in young adulthood (Haworth et al., 2010). Similarly, adopted children’s verbal ability scores over time become more like those of their biological parents (Figure 63.2). Who would have guessed?

Figure 63.2 In verbal ability, whom do adopted children resemble?

As the years went by in their adoptive families, children’s verbal ability scores became more like their biological parents’ scores.

“Selective breeding has given me an aptitude for the law, but I still love fetching a dead duck out of freezing water.”