Understanding Psychological Disorders

The way we view a problem influences how we try to solve it. In earlier times, people often viewed strange behaviors as evidence of strange forces—the movements of the stars, godlike powers, or evil spirits—at work. Had you lived during the Middle Ages, you might have said “The devil made him do it.” Believing that, you might have approved of a harsh cure that would drive out the evil demon. Thus, people considered “mad” were sometimes caged or given “therapies” such as genital mutilation, beatings, removal of teeth or lengths of intestines, or transfusions of animal blood (Farina, 1982).

Reformers such as Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) in France opposed such brutal treatments. Madness is not demonic possession, he insisted, but a sickness of the mind caused by severe stress and inhumane conditions. Curing the illness, he said, requires moral treatment, including boosting patients’ spirits by unchaining them and talking with them. He and others worked to replace brutality with gentleness, isolation with activity, and filth with clean air and sunshine.

“Moral treatment” Under Philippe Pinel’s influence, hospitals sometimes sponsored patient dances, often called “lunatic balls,” as depicted in this painting by George Bellows (Dance in a Madhouse).

In some places, cruel treatments for mental illness—including chaining people to beds or confining them in spaces with wild animals—linger even today. The World Health Organization has launched a reform that aims to transform hospitals worldwide “into patient-friendly and humane places with minimum restraints” (WHO, 2014a).

Yesterday’s “therapy” Through the ages, psychologically disordered people have received brutal treatments, including the trephination evident in this Stone Age patient’s skull. Drilling skull holes like these may have been an attempt to release evil spirits and cure those with mental disorders. Did this patient survive the “cure”?

The Medical Model

By the 1800s, a medical breakthrough prompted further reforms. Researchers discovered that syphilis infects the brain and distorts the mind. This discovery triggered an eager search for physical causes of other mental disorders and for treatments that would cure them. Hospitals replaced asylums, and the medical model of mental disorders was born. This model is reflected in the terms we still use today. We speak of the mental health movement: A mental illness (also called a psychopathology) needs to be diagnosed on the basis of its symptoms. It needs to be treated through therapy, which may include time in a psychiatric hospital.

The medical perspective has been energized by more recent discoveries that genetically influenced abnormalities in brain structure and biochemistry contribute to many disorders (Insel & Cuthbert, 2015). A growing number of clinical psychologists now work in medical hospitals, where they collaborate with physicians to determine how the mind and body operate together.

The Biopsychosocial Approach

To call psychological disorders “sicknesses” tilts research heavily toward the influence of biology and away from the influence of our personal histories and social and cultural surroundings. But in the study of disorders, as in so many other areas, biological, psychological, and social-cultural influences together weave the fabric of our behaviors, our thoughts, and our feelings. As individuals, we differ in the amount of stress we experience and in the ways we cope with stressors. Cultures also differ in their sources of stress and in their traditional ways of coping. We are physically embodied and socially embedded.

Two disorders—major depressive disorder and schizophrenia—occur worldwide. From Asia to Africa and across the Americas, schizophrenia’s symptoms often include irrationality and incoherent speech. Other disorders tend to be associated with specific cultures. Latin America lays claim to susto, a condition marked by severe anxiety, restlessness, and a fear of black magic. In Japanese culture, people may experience taijin-kyofusho—social anxiety about their appearance, combined with a readiness to blush and a fear of eye contact. The eating disorders anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa occur mostly in food-abundant Western cultures. Such disorders may share an underlying dynamic (such as anxiety) while differing in the symptoms (an eating problem or a type of fear) manifested in a particular culture. Even disordered aggression may have varying explanations in different cultures. In Malaysia, amok describes a sudden outburst of violent behavior (as in the English phrase “run amok”).

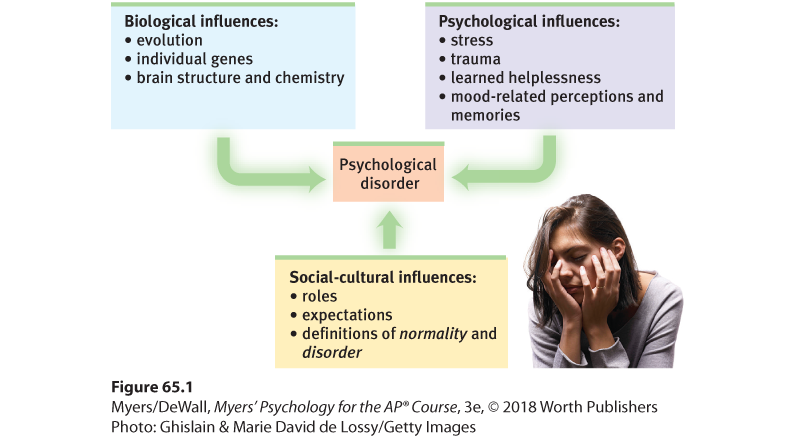

Disorders reflect genetic predispositions and physiological states, inner psychological dynamics, and social and cultural circumstances. The biopsychosocial approach emphasizes that mind and body are inseparable (Figure 65.1). Negative emotions can contribute to physical illness, and physical abnormalities can likewise contribute to negative emotions. The biopsychosocial approach gave rise to the stress vulnerability model (also called the diathesis-stress model). This model suggests that individual characteristics combine with environmental stressors to increase or decrease the likelihood of developing a psychological disorder (Monroe & Simons, 1991; Zuckerman, 1999). Research on epigenetics (literally, “in addition to genetic”) supports the vulnerability-stress model by showing how our DNA and our environment interact. In one environment, a gene will be expressed, but in another, it may lie dormant. For some, that will be the difference between developing a disorder or not developing it.

Figure 65.1 The biopsychosocial approach to psychological disorders

Today’s psychology studies how biological, psychological, and social-cultural factors interact to produce specific psychological disorders.