Personality Disorders

The inflexible and enduring behavior patterns of personality disorders interfere with social functioning. The ten disorders in DSM-5 tend to form three clusters, characterized by

- anxiety, such as a fearful sensitivity to rejection that predisposes the withdrawn avoidant personality disorder.

- eccentric or odd behaviors, such as the emotionless disengagement of schizotypal personality disorder.

- dramatic or impulsive behaviors, such as the attention-getting borderline personality disorder, the self-focused and self-inflating narcissistic personality disorder, and—what we next discuss as an in-depth example—the callous, and often dangerous, antisocial personality disorder.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

People with antisocial personality disorder, usually male, can display symptoms by age 8. Their lack of conscience becomes plain before age 15, as they begin to lie, steal, fight, or display unrestrained sexual behavior (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). Not all children with these traits become antisocial adults. (Note: “Antisocial” means disruptive, not just unsociable.) Those who do (about half of them) will generally act in violent or otherwise criminal ways, be unable to keep a job, and, if they have a spouse or children, behave irresponsibly toward them (Farrington, 1991). People with antisocial personality disorder (sometimes called sociopaths or psychopaths) may show lower emotional intelligence—the ability to understand, manage, and perceive emotions (Ermer et al., 2012).

Despite their remorseless and sometimes criminal behavior, criminality is not an essential component of antisocial behavior (Skeem & Cooke, 2010). Moreover, many criminals do not fit the description of antisocial personality disorder. Why? Because they’re not impulsive (Geurts et al., 2016). Rather, they actually show responsible concern for their friends and family members. When the antisocial personality combines a keen intelligence with amorality, the result may be a charming and clever con artist—or a fearless, focused, ruthless soldier, surgeon, or CEO (Dutton, 2012; Schutte et al., 2016).

No remorse Dennis Rader, known as the “BTK killer” in Kansas, was convicted in 2005 of killing 10 people over a 30-year span. Rader exhibited the extreme lack of conscience that marks antisocial personality disorder.

“Thursday is out. I have jury duty.”

Many criminals, like this one, exhibit a sense of conscience and responsibility in other areas of their life, and thus do not exhibit antisocial personality disorder.

Antisocial personalities behave impulsively, and then feel and fear little (Fowles & Dindo, 2009). Their impulsivity can have horrific consequences (Camp et al., 2013). Consider the case of Henry Lee Lucas. He killed his first victim when he was 13. He felt little regret then or later. During his years of crime, he brutally murdered 157 women, men, and children. For the last six years of his reign of terror, Lucas teamed with Ottis Elwood Toole, who reportedly slaughtered people he “didn’t think was worth living anyhow” (Darrach & Norris, 1984).

Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder

Antisocial personality disorder is woven of both biological and psychological strands. Twin and adoption studies reveal that biological relatives of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies are at increased risk for antisocial behavior (Frisell et al., 2012; Kendler et al., 2015b). People with antisocial personalities sometimes spread their genes to future generations by marrying others who have antisocial personalities (Weiss et al., 2017). No single gene codes for a complex behavior such as crime. Molecular geneticists have, however, identified some specific genes that are more common in those with antisocial personality disorder (Gunter et al., 2010).

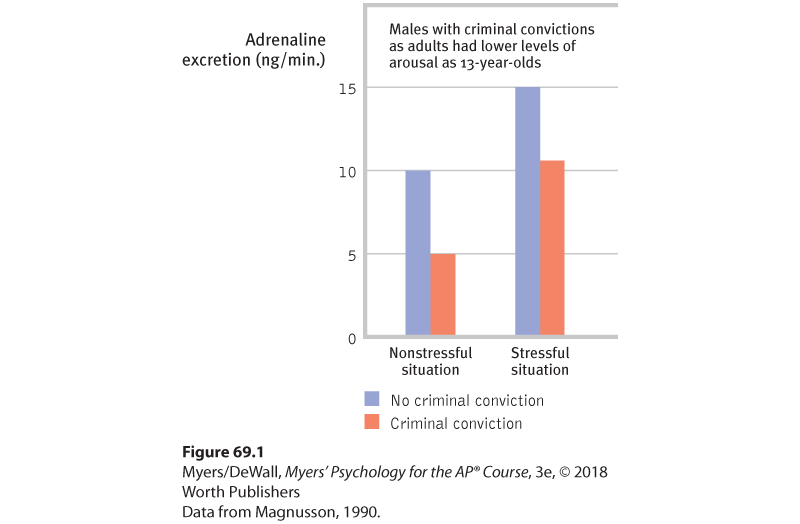

The genetic vulnerability of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies appears as low arousal in response to threats. Awaiting aversive events, such as electric shocks or loud noises, they show little autonomic nervous system arousal (Hare, 1975; Hoppenbrouwers et al., 2016). Long-term studies show that their stress hormone levels were lower than average as teenagers, before committing any crime (Figure 69.1). And those who were slow to develop conditioned fears at age 3 were also more likely to commit a crime later in life (Gao et al., 2010). Other studies have found that preschool boys who later became aggressive or antisocial adolescents tended to be impulsive, uninhibited, unconcerned with social rewards, and low in anxiety (Caspi et al., 1996; Tremblay et al., 1994).

Figure 69.1 Cold-blooded arousability and risk of crime

Levels of the stress hormone adrenaline were measured in two groups of 13-year-old Swedish boys. In both stressful and nonstressful situations, those who would later be convicted of a crime as 18- to 26-year-olds showed relatively low arousal.

Traits such as fearlessness and dominance can be adaptive. If channeled in more productive directions, fearlessness may lead to athletic stardom, adventurism, or courageous heroism (Smith et al., 2013). In one analysis, 42 American presidents scored higher than the general population on such traits as fearlessness and dominance (Lilienfeld et al., 2012, 2016). Patient S. M., a 49-year-old woman who experienced damage to her amygdala, showed fearlessness and impulsivity but also displayed acts of heroism (Lilienfeld et al., 2017). For example, she gave a man in need her only coat and scarf. Befriending a child with cancer, how did she respond? She cut her hair short and donated it to the Locks of Love charity.

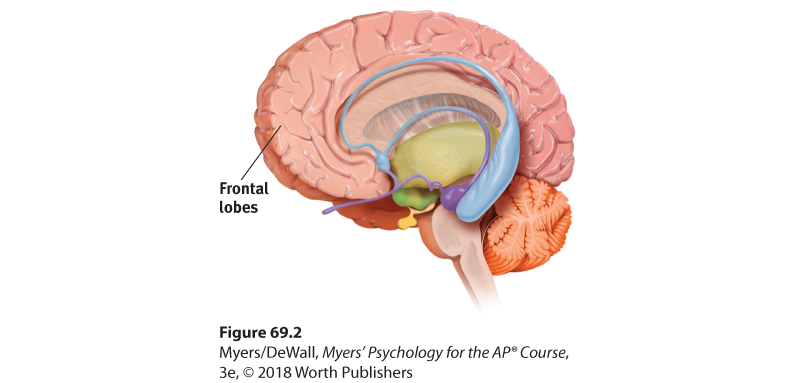

Genetic influences, often in combination with negative environmental factors such as childhood abuse, family instability, or poverty, help wire the brain (Dodge, 2009). In people with antisocial criminal tendencies, the emotion-controlling amygdala is smaller (Pardini et al., 2014). The frontal lobes are also less active, as Adrian Raine (1999, 2005) found when he compared PET scans of 41 murderers’ brains with those from people of similar age and sex (Figure 69.2). The frontal lobes help control impulses. The reduced activation was especially apparent in those who murdered impulsively. In a follow-up study, Raine and his team (2000) found that violent repeat offenders had 11 percent less frontal lobe tissue than normal. This helps explain why people with antisocial personality disorder exhibit marked deficits in frontal lobe cognitive functions, such as planning, organization, and inhibition (Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000). Compared with people who feel and display empathy, their brains also respond less to facial displays of others’ distress, which may contribute to their lower emotional intelligence (Deeley et al., 2006).

Figure 69.2 Murderous minds

Researchers have found reduced activation in a murderer’s frontal lobes. This brain area (shown in a left-facing brain) helps brake impulsive, aggressive behavior (Raine, 1999).

A biologically based fearlessness, as well as early environment, helps explain an unusual family reunion. Long-separated sisters Joyce Lott, 27, and Mary Jones, 29, came together at a place that normally separates family members rather than brings them together—a South Carolina prison where both were sent on drug charges. After a newspaper story about their reunion, their long-lost half-brother Frank Strickland called. But he had his own problem: He was stuck in jail on drug, burglary, and larceny charges (Shepherd et al., 1990). The genes that put people at risk for antisocial behavior also put people at risk for substance use disorders, which may help explain why these disorders often appear in combination (Dick, 2007).

Genetics alone do not tell the whole story of antisocial crime, however. In another Raine-led study (1996), researchers checked criminal records on nearly 400 Danish men at ages 20 to 22. All these men either had experienced biological risk factors at birth (such as premature birth) or came from family backgrounds marked by poverty and family instability. The researchers then compared each of these two groups with a third biosocial group (people whose lives were marked by both those biological and social risk factors). The biosocial group had double the risk of committing crime. Similar findings emerged from a famous study that followed 1037 children for a quarter-century: Two combined factors—childhood maltreatment and a gene that altered neurotransmitter balance—predicted antisocial problems (Caspi et al., 2002). Neither “bad” genes alone nor a “bad” environment alone predisposed later antisocial behavior. Rather, genes predisposed some children to be more sensitive to maltreatment. Within “genetically vulnerable segments of the population,” environmental influences matter—for better or for worse (Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Moffitt, 2005).

Battling with body image Many celebrities, including Lady Gaga, have struggled publicly with eating disorders.

With antisocial behavior, as with so much else, nature and nurture interact and the biopsychosocial perspective helps us understand the whole story. To explore the neural basis of antisocial personality disorder, neuroscientists are trying to identify brain activity differences in criminals who display symptoms of this disorder. Shown emotionally evocative photographs, such as a man holding a knife to a woman’s throat, criminals with antisocial personality disorder display blunted heart rate and perspiration responses, and less activity in brain areas that typically respond to emotional stimuli (Harenski et al., 2010; Kiehl & Buckholtz, 2010). They also have a larger and hyper-reactive dopamine reward system, which predisposes their impulsive drive to do something rewarding despite the consequences (Buckholtz et al., 2010; Glenn et al., 2010). Such data provide another reminder: Everything psychological is also biological.