Behavior Therapies

The insight therapies assume that self-awareness and psychological well-being go hand in hand. Psychodynamic therapists expect people’s problems to diminish as they gain insight into their unresolved and unconscious tensions. Humanistic therapists expect problems to diminish as people get in touch with their feelings. Behavior therapists, however, doubt the healing power of self-awareness. Rather than delving deeply below the surface looking for inner causes, behavior therapists assume that problem behaviors are the problems. (You can become aware of why you are highly anxious during tests and still be anxious.) If phobias, sexual dysfunctions, or other maladaptive symptoms are learned behaviors, why not apply learning principles to replace them with new, constructive behaviors?

Classical Conditioning Techniques

One cluster of behavior therapies derives from principles developed in Ivan Pavlov’s early twentieth-century conditioning experiments (Module 26). As Pavlov and others showed, we learn various behaviors and emotions through classical conditioning. If we’re attacked by a dog, we may thereafter have a conditioned fear response when other dogs approach. (Our fear generalizes, and all dogs become conditioned stimuli.)

Could maladaptive symptoms be examples of conditioned responses? If so, might reconditioning be a solution? Learning theorist O. H. Mowrer thought so. He developed a successful conditioning therapy for chronic bed-wetters, using a liquid-sensitive pad connected to an alarm. If the sleeping child wets the bed pad, moisture triggers the alarm, waking the child. After a number of trials, the child associates bladder relaxation with waking. In three out of four cases, the treatment has been effective and the success boosted the child’s self-image (Christophersen & Edwards, 1992; Houts et al., 1994).

Can we unlearn fear responses, such as to public speaking or flying, through new conditioning? Many people have. An example: The fear of riding in an elevator is often a learned aversion to being in a confined space. Counterconditioning, such as with exposure therapy, pairs the trigger stimulus (in this case, the enclosed space of the elevator) with a new response (relaxation) that is incompatible with fear.

Exposure Therapies

Picture this scene: Behavioral psychologist Mary Cover Jones is working with 3-year-old Peter, who is petrified of rabbits and other furry objects. To rid Peter of his fear, Jones plans to associate the fear-evoking rabbit with the pleasurable, relaxed response associated with eating. As Peter begins his midafternoon snack, she introduces a caged rabbit on the other side of the huge room. Peter, eagerly munching away on his crackers and drinking his milk, hardly notices. On succeeding days, she gradually moves the rabbit closer and closer. Within two months, Peter is holding the rabbit in his lap, even stroking it while he eats. Moreover, his fear of other furry objects subsides as well, having been countered, or replaced, by a relaxed state that cannot coexist with fear (Fisher, 1984; Jones, 1924).

Unfortunately for many who might have been helped by Jones’ counterconditioning procedures, her story of Peter and the rabbit did not enter psychology’s lore when it was reported in 1924. It was more than 30 years before psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe (1958; Wolpe & Plaud, 1997) refined Jones’ counterconditioning technique into the exposure therapies used today. These therapies, in a variety of ways, try to change people’s reactions by repeatedly exposing them to stimuli that trigger unwanted reactions. With repeated exposure to what they normally avoid or escape, people adapt. We all experience this process in everyday life. A person moving to a new apartment may be annoyed by nearby loud traffic noise, but only for a while. The person adapts. So, too, with people who have fear reactions to specific events. Exposed repeatedly to the situation that once petrified them, with support from talk therapy, they can learn to react less anxiously (Barrera et al., 2013; Foa & McLean, 2016).

One exposure therapy used to treat phobias is systematic desensitization. You cannot simultaneously be anxious and relaxed. Therefore, if you can repeatedly relax when facing anxiety-provoking stimuli, you can gradually eliminate your anxiety. The trick is to proceed gradually. If you fear public speaking, a behavior therapist might first help you construct a hierarchy of anxiety-triggering speaking situations. Yours might range from mildly anxiety-provoking situations (perhaps speaking up in a small group of friends) to panic-provoking situations (having to address a large audience).

Next, the therapist would train you in progressive relaxation. You would learn to release tension in one muscle group after another, until you achieve a comfortable, complete relaxation. Then the therapist might ask you to imagine, with your eyes closed, a mildly anxiety-arousing situation: You are having coffee with a group of friends and are trying to decide whether to speak up. If imagining the scene causes you to feel any anxiety, you will signal by raising your finger. Seeing the signal, the therapist will instruct you to switch off the mental image and go back to deep relaxation. This imagined scene is repeatedly paired with relaxation until you feel no trace of anxiety.

The therapist will then move to the next item in your anxiety hierarchy, again using relaxation techniques to desensitize you to each imagined situation. After several sessions, you move to actual situations and practice what you had only imagined before, beginning with relatively easy tasks and gradually moving to more anxiety-filled ones. Conquering your anxiety in an actual situation, not just in your imagination, will increase your self-confidence (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Williams, 1987). Eventually, you may even become a confident public speaker. Often people fear not just a situation, such as public speaking, but also being incapacitated by their own fear response. As their fear subsides, so also does their fear of the fear.

“ The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt First inaugural address, 1933

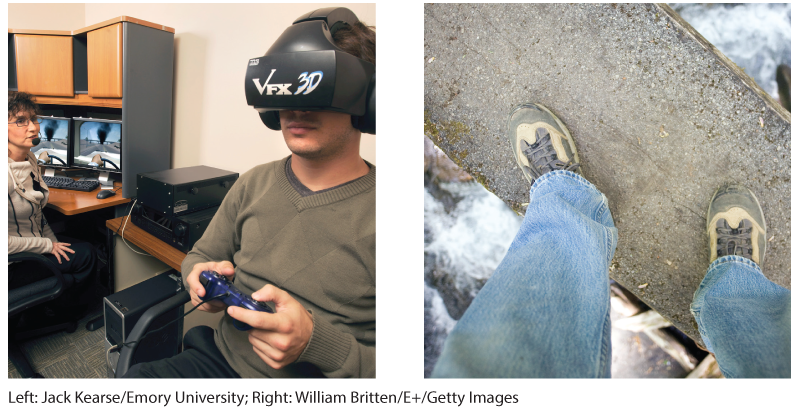

If an anxiety-arousing situation is too expensive, difficult, or embarrassing to re-create, the therapist may recommend virtual reality exposure therapy. You would don a head-mounted display unit that projects a three-dimensional virtual world. The lifelike scenes, which shift as your head turns, would be tailored to your particular fear. Experimentally treated fears include flying, heights, particular animals, and public speaking (Parsons & Rizzo, 2008). If you fear flying, you could peer out a virtual window of a simulated plane, feel the engine’s vibrations, and hear it roar as the plane taxis down the runway and takes off. In controlled studies, people participating in virtual reality exposure therapy have experienced significant relief from real-life fear (Turner & Casey, 2014).

Virtual reality exposure therapy Within the confines of a room, virtual reality technology exposes people to vivid simulations of feared stimuli, such as walking across a rickety bridge high off the ground.

Aversive Conditioning

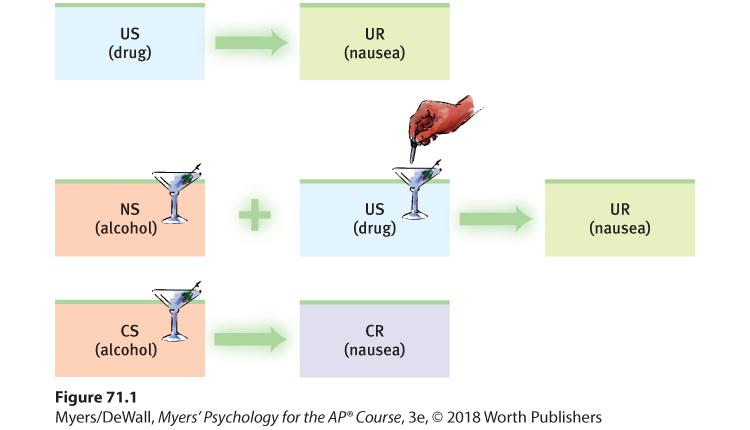

An exposure therapy enables a more relaxed, positive response to an upsetting harmless stimulus. It helps you accept what you should do. Aversive conditioning creates a negative (aversive) response to a harmful stimulus (such as alcohol). It helps you to learn what you should not do. The aversive conditioning procedure is simple: It associates the unwanted behavior with unpleasant feelings. To treat nail biting, the therapist may suggest painting the fingernails with a nasty-tasting nail polish (Baskind, 1997). To treat alcohol use disorder, the therapist may offer the client appealing drinks laced with a drug that produces severe nausea (recall the taste-aversion experiments with rats and coyotes in Module 29). If that therapy links alcohol with violent nausea, the person’s reaction to alcohol may change from positive to negative (Figure 71.1).

Figure 71.1 Aversion therapy for alcohol use disorder

After repeatedly imbibing an alcoholic drink mixed with a drug that produces severe nausea, some people with a history of alcohol use disorder develop at least a temporary conditioned aversion to alcohol. (Remember: US is unconditioned stimulus, UR is unconditioned response, NS is neutral stimulus, CS is conditioned stimulus, and CR is conditioned response.)

Flip It Video: Counterconditioning—How It Works

Flip It Video: Counterconditioning—How It Works

Taste aversion learning has been a successful alternative to killing predators in some animal protection programs (Dingfelder, 2010; Garcia & Gustavson, 1997). After being sickened by eating a contaminated sheep, wolves may avoid sheep. Does aversive conditioning also transform humans’ reactions to alcohol? In the short run it may. In one classic study, 685 hospital patients with alcohol use disorder completed an aversion therapy program (Wiens & Menustik, 1983). Over the next year, they returned for several booster treatments that paired alcohol with sickness. At the end of that year, 63 percent were not drinking alcohol. But after three years, only 33 percent were alcohol free.

In therapy, as in research, cognition influences conditioning. People know that outside the therapist’s office they can drink without fear of nausea. Just as animals learn to expect how often they will experience an unconditioned stimulus (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972), people can learn a probability that drinking will lead to nausea. This ability to discriminate between the therapy situation and all others can limit aversive conditioning’s effectiveness. Thus, therapists often combine aversive conditioning with other treatments.

Operant Conditioning Techniques

If you have learned to swim, you learned how to put your head under water without suffocating, how to pull your body through the water, and perhaps even how to dive safely. Operant conditioning shaped your swimming. You were reinforced for safe, effective behaviors. And you were naturally punished, as when you swallowed water, for improper swimming behaviors.

Pioneering researcher B. F. Skinner helped us understand the basic principle of operant conditioning (Modules 27 and 28): Consequences strongly influence our voluntary behaviors. Knowing this, behavior therapists can practice behavior modification. They reinforce behaviors they consider desirable, and they fail to reinforce—or sometimes punish—behaviors they consider undesirable.

Using operant conditioning to solve specific behavior problems has raised hopes for some seemingly hopeless cases. Children with intellectual disabilities have been taught to care for themselves. Socially withdrawn children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have learned to interact. People with schizophrenia have been helped to behave more rationally in their hospital ward. In such cases, therapists used positive reinforcers to shape behavior. In a step-by-step manner, they rewarded closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior.

In extreme cases, treatment must be intensive. One study worked with 19 withdrawn, uncommunicative 3-year-olds with ASD. For two years, 40 hours each week, the children’s parents attempted to shape their behavior (Lovaas, 1987). They positively reinforced desired behaviors and ignored or punished aggressive and self-abusive behaviors. The combination worked wonders for some children. By first grade, 9 of the 19 were functioning successfully in school and exhibiting normal intelligence. In a group of 40 comparable children not undergoing this effortful treatment, only one showed similar improvement. Later studies focused on positive reinforcement—the effective aspect of this early intensive behavioral intervention (Reichow, 2012).

Rewards used to modify behavior vary. For some people, the reinforcing power of attention or praise is sufficient. Others require concrete rewards, such as food. In institutional settings, therapists may create a token economy. When people display a desired behavior, such as getting out of bed, washing, dressing, eating, talking coherently, cleaning up their rooms, or playing cooperatively, they receive a token or plastic coin. Later, they can exchange a number of these tokens for rewards, such as candy, TV time, day trips, or better living quarters. Token economies have been used successfully in homes, classrooms, and detention facilities, and among people with various disabilities (Matson & Boisjoli, 2009).

Behavior modification critics express two concerns:

- How durable are the behaviors? Will people become so dependent on extrinsic rewards that the desired behaviors will stop when reinforcers stop? Behavior modification advocates believe the behaviors will endure if therapists wean people from the tokens by shifting them toward other, real-life rewards, such as social approval. Further, they point out, the desired behaviors themselves can be rewarding. As people become more socially competent, the intrinsic satisfactions of social interaction may sustain the behaviors.

- Is it right for one human to control another’s behavior? Those who set up token economies deprive people of something they desire and decide which behaviors to reinforce. To critics, this whole process feels too authoritarian. Advocates reply that control already exists: People’s destructive behavior patterns are being maintained and perpetuated by natural reinforcers and punishers in their environments. Isn’t using positive rewards to reinforce adaptive behavior more humane than institutionalizing or punishing people? Advocates also argue that the right to effective treatment and an improved life justifies temporary deprivation.