Cognitive Therapies

People with specific fears and problem behaviors may respond to behavior therapy. But how might behavior therapists modify the wide assortment of behaviors that accompany depressive disorders? Or treat people with generalized anxiety disorder, where unfocused anxiety doesn’t lend itself to a neat list of anxiety-triggering situations? The cognitive revolution that has profoundly changed other areas of psychology during the last half-century has influenced therapy as well (Module 2).

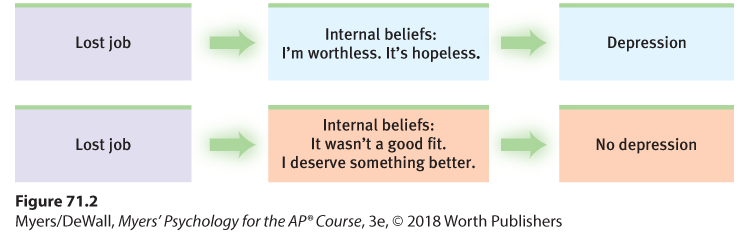

The cognitive therapies assume that our thinking colors our feelings (Figure 71.2). Between an event and our response lies the mind. Self-blaming and overgeneralized explanations of bad events feed depression (Module 67). Anxiety arises from an “attention bias to threat” (MacLeod & Clarke, 2015). If depressed, we may interpret a suggestion as criticism, disagreement as dislike, praise as flattery, friendliness as pity. Dwelling on such thoughts sustains negative thinking. Cognitive therapies aim to help people change their mind with new, more constructive ways of perceiving and interpreting events (Kazdin, 2015).

Figure 71.2 A cognitive perspective on psychological disorders

The person’s emotional reactions are produced not directly by the event but by the person’s thoughts in response to the event.

Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy

According to Albert Ellis (1962, 1987, 1993), the creator of rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT), many problems arise from irrational thinking. For example, he described how therapy might challenge one client’s illogical, self-defeating assumptions (Ellis, 2011, pp. 198–199):

[She] does not merely believe it is undesirable if her lover rejects her. She tends to believe, also, that (a) it is awful; (b) she cannot stand it; (c) she should not, must not be rejected; (d) she will never be accepted by any desirable partner; (e) she is a worthless person because one lover has rejected her; and (f) she deserves to be rejected for being so worthless. Such common covert [hidden] hypotheses are illogical, unrealistic, and destructive. . . . They can be easily elicited and demolished by any scientist worth his or her salt; and the rational-emotive therapist is exactly that: an exposing and nonsense-annihilating scientist.

Change people’s thinking by revealing the “absurdity” of their self-defeating ideas, the sharp-tongued Ellis believed, and you will change their self-defeating feelings and enable healthier behaviors.

Beck’s Therapy for Depression

In the late 1960s, a woman left a party early. Things had not gone well. She felt disconnected from the other party-goers and assumed no one cared for her. A few days later, she visited therapist Aaron Beck. Rather than go down the traditional path to her childhood, Beck challenged her thinking. After she then listed a dozen people who did care for her, Beck realized that challenging people’s automatic negative thoughts could be therapeutic. And thus was born his cognitive therapy, which assumes that changing people’s thinking can change their functioning (Spiegel, 2015).

“ Life does not consist mainly, or even largely, of facts and happenings. It consists mainly of the storm of thoughts that are forever blowing through one’s mind.”

Mark Twain, 1835–1910

Depressed people, Beck found, often reported dreams with negative themes of loss, rejection, and abandonment. These thoughts extended into their waking thoughts, and even into therapy, as clients recalled and rehearsed their failings and worst impulses (Kelly, 2000). With cognitive therapy, Beck and his colleagues (1979) sought to reverse clients’ negativity about themselves, their situations, and their futures. With this technique, gentle questioning seeks to reveal irrational thinking, and then to persuade people to remove the dark glasses through which they view life (Beck et al., 1979, pp. 145–146):

Client: I agree with the descriptions of me but I guess I don’t agree that the way I think makes me depressed.

Beck: How do you understand it?

Client: I get depressed when things go wrong. Like when I fail a test.

Beck: How can failing a test make you depressed?

Client: Well, if I fail I’ll never get into law school.

Beck: So failing the test means a lot to you. But if failing a test could drive people into clinical depression, wouldn’t you expect everyone who failed the test to have a depression? . . . Did everyone who failed get depressed enough to require treatment?

Client: No, but it depends on how important the test was to the person.

Beck: Right, and who decides the importance?

Client: I do.

Beck: And so, what we have to examine is your way of viewing the test (or the way that you think about the test) and how it affects your chances of getting into law school. Do you agree?

Client: Right.

Beck: Do you agree that the way you interpret the results of the test will affect you? You might feel depressed, you might have trouble sleeping, not feel like eating, and you might even wonder if you should drop out of the course.

Client: I have been thinking that I wasn’t going to make it. Yes, I agree.

Beck: Now what did failing mean?

Client: (tearful) That I couldn’t get into law school.

Beck: And what does that mean to you?

Client: That I’m just not smart enough.

Beck: Anything else?

Client: That I can never be happy.

Beck: And how do these thoughts make you feel?

Client: Very unhappy.

Beck: So it is the meaning of failing a test that makes you very unhappy. In fact, believing that you can never be happy is a powerful factor in producing unhappiness. So, you get yourself into a trap—by definition, failure to get into law school equals “I can never be happy.”

We often think in words. Therefore, getting people to change what they say to themselves is an effective way to change their thinking. Perhaps you can identify with the anxious students who, before a test, make matters worse with self-defeating thoughts: “This test’s probably going to be impossible. Everyone seems so relaxed and confident. I wish I were better prepared. I’m so nervous I’ll forget everything.” Psychologists call this sort of relentless, overgeneralized, self-blaming behavior catastrophizing.

To change such negative self-talk, therapists have offered stress inoculation training: teaching people to restructure their thinking in stressful situations (Meichenbaum, 1977, 1985). Sometimes it may be enough simply to say more positive things to oneself: “Relax. The test may be hard, but it will be hard for everyone else, too. I studied harder than most people. Besides, I don’t need a perfect score to get a good grade.” After learning to “talk back” to negative thoughts, depression-prone children, teens, and college students have shown a greatly reduced rate of future depression (Reivich et al., 2013; Seligman et al., 2009). To a large extent, it is the thought that counts. For a sampling of commonly used cognitive therapy techniques, see Table 71.1.)

| Aim of Technique | Technique | Therapists’ Directives |

|---|---|---|

| Reveal beliefs | Question your interpretations | Explore your beliefs, revealing faulty assumptions such as “I need to be liked by everyone.” |

| Rank thoughts and emotions | Gain perspective by ranking your thoughts and emotions from mildly to extremely upsetting. | |

| Test beliefs | Examine consequences | Explore difficult situations, assessing possible consequences and challenging faulty reasoning. |

| Decatastrophize thinking | Work through the actual worst-case consequences of the situation you face (it is often not as bad as imagined). Then determine how to cope with the real situation you face. | |

| Change beliefs | Take appropriate responsibility | Challenge total self-blame and negative thinking, noting aspects for which you may be truly responsible, as well as aspects that aren’t your responsibility. |

| Resist extremes | Develop new ways of thinking and feeling to replace maladaptive habits. For example, change from thinking “I am a total failure” to “I got a failing grade on that paper, and I can make these changes to succeed next time.” |

PEANUTS

It’s not just depressed people who can benefit from positive self-talk. We all talk to ourselves (thinking “I wish I hadn’t said that” can protect us from repeating the blunder). The findings of nearly three dozen sport psychology studies show that self-talk interventions can enhance the learning of athletic skills (Hatzigeorgiadis et al., 2011). For example, novice basketball players may be trained to think “focus” and “follow through,” swimmers to think “high elbow,” and tennis players to think “look at the ball.” People anxious about public speaking have grown in confidence if asked to recall a speaking success, and then to “Explain WHY you were able to achieve such a successful performance” (Zunick et al., 2015).

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

“The trouble with most therapy,” said Ellis, “is that it helps you to feel better. But you don’t get better. You have to back it up with action, action, action.” Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) takes a combined approach to depression and other disorders. This widely practiced integrative therapy aims to alter not only the way people think but also the way they act. Like other cognitive therapies, CBT seeks to make people aware of their irrational negative thinking and to replace it with new ways of thinking. And like other behavior therapies, it trains people to practice the more positive approach in everyday settings.

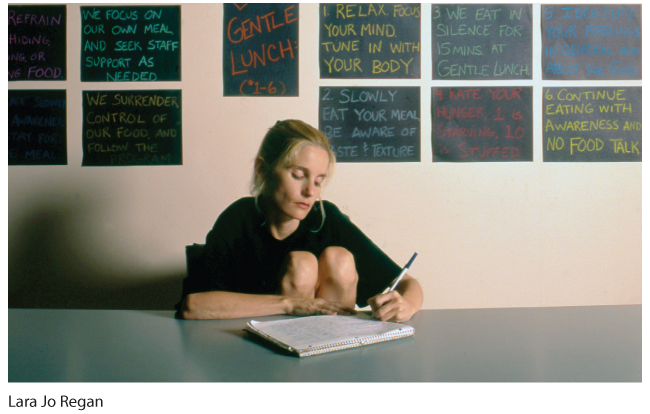

Cognitive therapy for eating disorders aided by journaling Cognitive therapists guide people toward new ways of explaining their good and bad experiences. By recording positive events and how she has enabled them, this woman may become more mindful of her self-control and more optimistic.

Anxiety, depressive disorders, and bipolar disorder share a common problem: emotion regulation (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010; Szkodny et al., 2014). An effective CBT program for these emotional disorders trains people both to replace their catastrophizing thinking with more realistic appraisals, and, as homework, to practice behaviors that are incompatible with their problem (Kazantzis et al., 2010a,b; Moses & Barlow, 2006). A person might keep a log of daily situations associated with negative and positive emotions, and engage more in activities that lead to feeling good. Those who fear social situations might learn to restrain the negative thoughts surrounding their social anxiety and practice approaching people.

CBT effectively treats people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Öst et al., 2015). In one classic study, people learned to prevent their compulsive behaviors by relabeling their obsessive thoughts (Schwartz et al., 1996). Feeling the urge to wash their hands again, they would tell themselves, “I’m having a compulsive urge.” They would explain to themselves that the hand-washing urge was a result of their brain’s abnormal activity, which they had previously viewed in PET scans. Then, instead of giving in, they would spend 15 minutes in an enjoyable, alternative behavior—practicing an instrument, taking a walk, gardening. This helped “unstick” the brain by shifting attention and engaging other brain areas. For two or three months, the weekly therapy sessions continued, with relabeling and refocusing practice at home. By the study’s end, most participants’ symptoms had diminished and their PET scans revealed normalized brain activity. Many other studies confirm CBT’s effectiveness for treating anxiety, depression, and eating disorders (Cristea et al., 2015; Milrod et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2016). Even online CBT quizzes and exercises—therapy without a face-to-face therapist—have helped alleviate insomnia, depression, and anxiety (Andersson, 2016; Christensen et al., 2016; Kampmann et al., 2016; Vigerland et al., 2016).

A newer CBT variation, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), helps change harmful and even suicidal behavior patterns (Linehan et al., 2015; Mehlum et al., 2016; Valentine et al., 2015). Dialectical means “opposing,” and this therapy attempts to make peace between two opposing forces—acceptance and change. Therapists create an accepting and encouraging environment, helping clients feel they have an ally who will offer them constructive feedback and guidance. In individual sessions, clients learn new ways of thinking that help them tolerate distress and regulate their emotions. They also receive training in social skills and in mindfulness meditation, which helps alleviate depression (Gu et al., 2015; Kuyken et al., 2016). Group training sessions offer additional opportunities to practice new skills in a social context, with further practice as homework.