Obedience: Following Orders

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974), a high school classmate of Philip Zimbardo and then a student of Solomon Asch, knew that people often give in to social pressures. But what about outright commands? Would they respond as did those who carried out Holocaust atrocities? (Some of Milgram’s family members were Nazi concentration camp survivors.) To find out, he undertook what have become social psychology’s most famous and controversial experiments (Benjamin & Simpson, 2009).

Stanley Milgram (1933–1984) This social psychologist’s obedience experiments “belong to the self-understanding of literate people in our age” (Sabini, 1986).

Imagine yourself as one of the nearly 1000 people who took part in Milgram’s 20 experiments. You respond to an ad for participants in a Yale University psychology study of the effect of punishment on learning. Professor Milgram’s assistant asks you and another person to draw slips from a hat to see who will be the “teacher” and who will be the “learner.” You draw a “teacher” slip (unknown to you, both slips say “teacher”). The supposed learner, a mild and submissive-seeming man, is led to an adjoining room and strapped into a chair. From the chair, wires run through the wall to your machine. You sit down in front of a shock machine and are given your task: Teach and then test the learner on a list of word pairs. If the learner gives a wrong answer, you are to flip a switch to deliver a brief electric shock. For the first wrong answer, you will flip the switch labeled “15 Volts—Slight Shock.” With each succeeding error, you will move to the next higher voltage. With each flip of a switch, lights flash and electronic switches buzz.

The experiment begins, and you deliver the shocks after the first and second wrong answers. If you continue, you hear the learner grunt when you flick the third, fourth, and fifth switches. After you activate the eighth switch (“120 Volts—Moderate Shock”), the learner cries out that the shocks are painful. After the tenth switch (“150 Volts—Strong Shock”), he begins shouting. “Get me out of here! I won’t be in the experiment anymore! I refuse to go on!” You draw back, but the stern experimenter prods you: “Please continue—the experiment requires that you continue.” You resist, but the experimenter insists, “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” or “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

If you obey, you hear the learner shriek in apparent agony as you continue to raise the shock level after each new error. After the 330-volt level, the learner refuses to answer and falls silent. Still, the experimenter pushes you toward the final, 450-volt switch. “Ask the question,” he says, “and if no correct answer is given, administer the next shock level.”

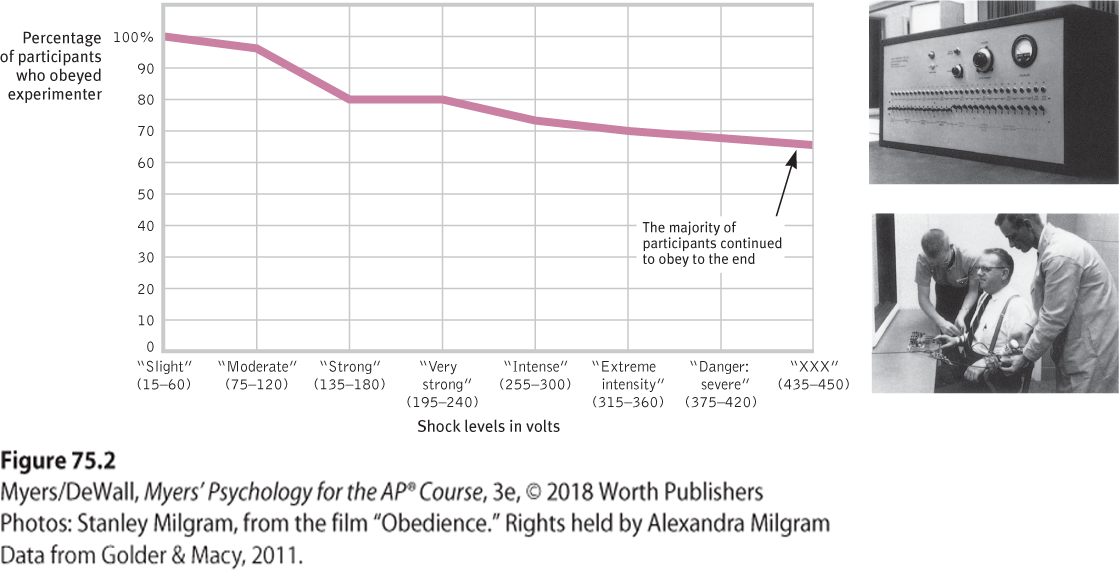

Would you follow the experimenter’s commands to shock someone? At what level would you refuse to obey? Before undertaking the experiments, Milgram asked nonparticipants what they would do. Most were sure they would stop soon after the learner first indicated pain, certainly before he shrieked in agony. Forty psychiatrists agreed with that prediction. Were the predictions accurate? Not even close. When Milgram conducted the experiment with other men aged 20 to 50, he was astonished. More than 60 percent complied fully—right up to the last switch. When he ran a new study, with 40 new “teachers” and a learner who complained of a “slight heart condition,” the results were similar. A full 65 percent of the new teachers obeyed the experimenter, right up to 450 volts (Figure 75.2). In 10 later studies, women obeyed at rates similar to men’s (Blass, 1999).

Figure 75.2 Milgram’s follow-up obedience experiment

In a repeat of the earlier experiment, 65 percent of the adult male “teachers” fully obeyed the experimenter’s commands to continue. They did so despite the “learner’s” earlier mention of a heart condition and despite hearing cries of protest after they administered what they thought were 150 volts and agonized protests after 330 volts.

Were Milgram’s results a product of the 1960s American mindset? No. When one researcher substantially repeated Milgram’s basic experiment, 70 percent of the participants complied up to the 150-volt point—only a slight reduction from Milgram’s 83 percent at that level (Burger, 2009). A Polish research team found 90 percent compliance to the same level (Dolin´ski et al., 2017). When a French reality TV show replicated Milgram’s study, 81 percent of the teachers, egged on by a cheering audience, obeyed and tortured a screaming victim (Beauvois et al., 2012).

Did Milgram’s teachers figure out the hoax—that no real shock was being delivered and the learner was in fact a confederate pretending to feel pain? Did they realize the experiment was really testing their willingness to comply with commands to inflict punishment? No. The teachers typically displayed genuine distress: They perspired, trembled, laughed nervously, and bit their lips.

Milgram’s use of deception and stress triggered a debate over his research ethics. In his own defense, Milgram pointed out that, after the participants learned of the deception and actual research purposes, virtually none regretted taking part (though perhaps by then the participants had reduced their cognitive dissonance—the discomfort they felt when their actions conflicted with their attitudes). When 40 of the teachers who had agonized most were later interviewed by a psychiatrist, none appeared to be suffering emotional aftereffects. All in all, said Milgram, the experiments provoked less enduring stress than university students experience when facing and failing big exams (Blass, 1996). Other scholars, however, after delving into Milgram’s archives, report that his debriefing was less extensive and his participants’ distress greater than he had suggested (Nicholson, 2011; Perry, 2013). Critics have also speculated that participants may have been identifying with the researcher and his scientific goals rather than being blindly obedient (Haslam et al., 2014, 2016).

In later experiments, Milgram discovered some conditions that influence people’s behavior. When he varied the situation, full obedience ranged from 0 to 93 percent. Obedience was highest when

- the person giving the orders was close at hand and was perceived to be a legitimate authority figure. Such was the case in 2005 when Temple University’s basketball coach sent a 250-pound bench player, Nehemiah Ingram, into a game with instructions to commit “hard fouls.” Following orders, Ingram fouled out in four minutes after breaking an opposing player’s right arm.

- the authority figure was supported by a powerful or prestigious institution. Compliance was somewhat lower when Milgram dissociated his experiments from Yale University. People have wondered: Why, during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, did so many Hutu citizens slaughter their Tutsi neighbors? It was partly because they were part of “a culture in which orders from above, even if evil,” were understood as having the force of law (Kamatali, 2014).

- the victim was depersonalized or at a distance, even in another room. Similarly, many soldiers in combat either have not fired their rifles at an enemy they could see, or have not aimed them properly. Such refusals to kill are rarer among soldiers operating long-distance artillery or aircraft weapons (Padgett, 1989). Those who kill from a distance—by operating remotely piloted drones—also suffer much less posttraumatic stress than do veterans of on-the-ground conflict (Miller, 2012).

- there were no role models for defiance. “Teachers” did not see any other participant disobey the experimenter.

The power of legitimate, close-at-hand authorities was apparent among those who followed orders to carry out the Nazis’ Holocaust atrocities. Obedience alone does not explain the Holocaust—anti-Semitic ideology produced eager killers as well (Fenigstein, 2015; Mastroianni, 2015). But obedience was a factor. In the summer of 1942, nearly 500 middle-aged German reserve police officers were dispatched to German-occupied Jozefow, Poland. On July 13, the group’s visibly upset commander informed his recruits, mostly family men, of their orders. They were to round up the village’s Jews, who were said to be aiding the enemy. Able-bodied men would be sent to work camps, and the rest would be shot on the spot.

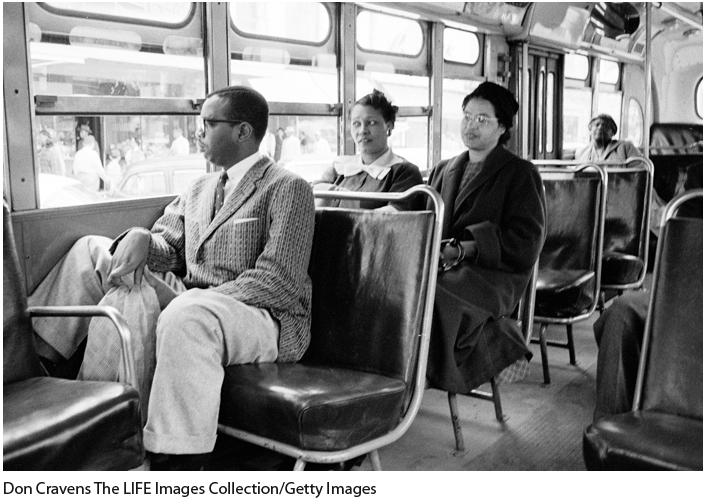

The power of disobedience The American civil rights movement was ignited when one African American woman, Rosa Parks, was arrested after spontaneously refusing to relinquish her Montgomery, Alabama, bus seat to a White man.

The commander gave the recruits a chance to refuse to participate in the executions. Only about a dozen immediately refused. Within 17 hours, the remaining 485 officers killed 1500 helpless women, children, and elderly, shooting them in the back of the head as they lay face down. Hearing the victims’ pleas, and seeing the gruesome results, some 20 percent of the officers did eventually dissent, managing either to miss their victims or to slip away and hide until the slaughter was over (Browning, 1992). In real life, as in Milgram’s experiments, those who resisted usually did so early, and they were the minority.

A different story played out in the French village of Le Chambon. There, villagers openly defied orders to cooperate with the “New Order”: They sheltered French Jews destined for deportation to Germany, and they sometimes helped them escape across the Swiss border. The villagers’ Protestant ancestors had themselves been persecuted, and their pastors taught them to “resist whenever our adversaries will demand of us obedience contrary to the orders of the Gospel” (Rochat, 1993). Ordered by police to give a list of sheltered Jews, the head pastor modeled defiance: “I don’t know of Jews, I only know of human beings.” At great personal risk, the people of Le Chambon made an initial commitment to resist. Throughout the long and terrible war, they suffered poverty and were punished for their disobedience. Still, supported by their beliefs, their role models, their interactions with one another, and their own initial acts, they remained defiant to the war’s end.

Lest we presume that obedience is always evil and resistance is always good, consider the heroic obedience of British soldiers who, in 1852, were traveling with civilians aboard the steamship Birkenhead. As they neared their South African port, the Birkenhead became impaled on a rock. To calm the passengers and permit an orderly exit of civilians on the three available lifeboats, soldiers who were not assisting the passengers or working the pumps lined up at parade rest. “Steady, men!” said their officer as the lifeboats pulled away. Heroically, no one frantically rushed to claim a lifeboat seat. As the boat sank, all were plunged into the sea, most to be drowned or devoured by sharks. For almost a century, noted James Michener (1978), “the Birkenhead drill remained the measure by which heroic behavior at sea was measured.”