Group Polarization

We live in an increasingly polarized world. The Middle East is torn by warring factions. The European Union is struggling with nationalist divisions. In 1990, a one-minute speech in the U.S. Congress would enable you to guess the speaker’s party just 55 percent of the time; by 2009, partisanship was evident 83 percent of the time (Gentzkow et al., 2016). In 2016, for the first time in survey history, most U.S. Republicans and Democrats reported having “very unfavorable” views of the other party (Doherty & Kiley, 2016). And a record 77 percent of Americans perceived their nation as divided (Jones, 2016).

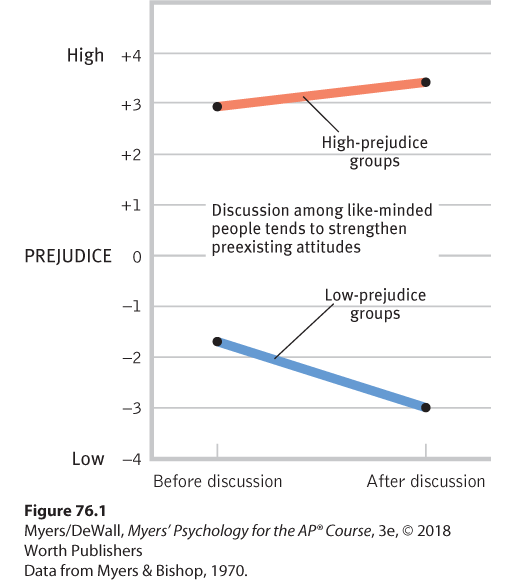

A powerful principle helps us understand our increasingly polarized world: The beliefs and attitudes we bring to a group grow stronger as we discuss them with like-minded others. This process, called group polarization, can have beneficial results, as when low-prejudice students become even more accepting while discussing racial issues. And it can be socially toxic, as when high-prejudice students who discuss racial issues become more prejudiced (Myers & Bishop, 1970; Figure 76.1). The repeated finding: Like minds polarize.

Figure 76.1 Group polarization

If a group is like-minded, discussion strengthens its prevailing opinions. Talking over racial issues increased prejudice in a high-prejudice group of high school students and decreased it in a low-prejudice group.

Analyses of terrorist organizations reveal that the terrorist mentality emerges slowly among people who share a grievance (McCauley, 2002; McCauley & Segal, 1987; Merari, 2002). As they interact in isolation (sometimes with other “brothers” and “sisters” in camps or in prisons), their views grow more and more extreme. Increasingly, they categorize the world as “us” against “them” (Chulov, 2014; Moghaddam, 2005). Knowing that group polarization occurs when like-minded people segregate, a 2006 U.S. National Intelligence estimate speculated that “the operational threat from self-radicalized cells will grow.”

“ What explains the rise of fascism in the 1930s? The emergence of student radicalism in the 1960s? The growth of Islamic terrorism in the 1990s? . . . The unifying theme is simple: When people find themselves in groups of like-minded types, they are especially likely to move to extremes. [This] is the phenomenon of group polarization.”

The Internet offers us a connected global world, yet also provides an easily accessible medium for group polarization. When I [DM] got my start in social psychology with experiments on group polarization, I never imagined the potential dangers, or the creative possibilities, of polarization in virtual groups. On the plus side, I can network with other advocates of accessibility for people with hearing loss. On the minus side, the Internet enables opinion bubbles: Progressives friend progressives and share links to sites that affirm their shared views. Conservatives connect with conservatives and likewise share conservative perspectives. With news feeds and retweets, we feed one another information—and misinformation—and click on content we agree with (Bakshy et al., 2015; Barberá et al., 2015). Thus, within the Internet’s echo chamber of the like-minded, views become more extreme. Suspicion becomes conviction. Disagreements with the other tribe can escalate to demonization. (For more on the Internet’s role in group polarization—toward ends that are good as well as bad—see Thinking Critically About: The Internet as Social Amplifier.)

“ Dear Satan, thank you for having my Internet news feeds tailored especially for ME!”

Comedian Steve Martin, 2016 tweet