The Psychology of Attraction

We endlessly wonder how we can win others’ affection and what makes our own affections flourish or fade. Does familiarity breed contempt, or does it amplify affection? Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? Is it what’s inside that counts, or does physical attractiveness matter too? To explore these questions, let’s consider three ingredients of our liking for one another: proximity, attractiveness, and similarity.

Familiarity breeds acceptance When this rare white penguin was born in the Sydney, Australia zoo, his tuxedoed peers ostracized him. Zookeepers thought they would need to dye him black to gain acceptance. But after three weeks of contact, the other penguins came to accept him.

Proximity

Before friendships become close, they must begin. Proximity—geographic nearness—is friendship’s most powerful predictor. Proximity can provide opportunities for aggression. But much more often it breeds liking (and sometimes even marriage) among those who live in the same neighborhood, sit nearby in class, work in the same office, share the same parking lot, or eat in the same cafeteria. Look around. Matching starts with meeting.

Proximity breeds liking partly because of the mere exposure effect. Repeated exposure to novel stimuli increases our liking for them. By age 3 months, infants prefer photos of the race they most often see—usually their own race (Kelly et al., 2007). For our ancestors, this mere exposure effect likely had survival value. What was familiar was generally safe and approachable. What was unfamiliar was more often dangerous and threatening. Evolution may therefore have hard-wired into us the tendency to bond with those who are familiar and to be wary of those whose looks are unfamiliar (Sofer et al., 2015; Zajonc, 1998).

Mere exposure increases our liking not only for familiar faces, but also for nonsense syllables, musical selections, geometric figures, Chinese characters, and the letters of our own name (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982; Nuttin, 1987; Zajonc, 2001). So, within certain limits, familiarity feeds fondness (Bornstein, 1989, 1999). This would come as no surprise to the young Taiwanese man who wrote more than 700 letters to his girlfriend, urging her to marry him. She did marry—the mail carrier (Steinberg, 1993).

No face is more familiar than your own. And that helps explain an interesting finding by Lisa DeBruine (2002, 2004): We like other people when their faces incorporate some morphed features of our own. When McMaster University students played a game with a supposed other player, they were more trusting and cooperative when the other person’s image had some of their own facial features morphed into it. In me I trust.

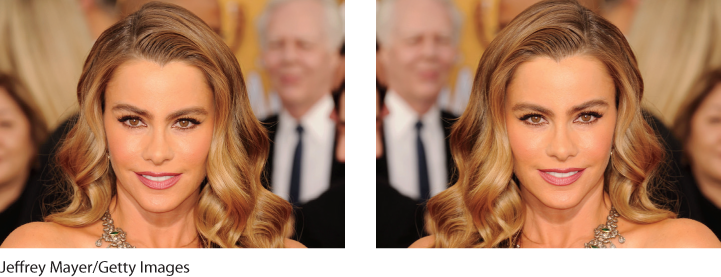

Which is the real Sofía Vergara? The mere exposure effect applies even to ourselves. Because the human face is not perfectly symmetrical, the face we see in the mirror is not the same face our friends see. Most of us prefer the familiar mirror image, while our friends like the reverse (Mita et al., 1977). The person actress Sofía Vergara sees in the mirror each morning is shown at right, and that’s the photo she would probably prefer.

Modern Matchmaking

Adults who have not found a romantic partner in their immediate proximity may cast a wider net by joining an online dating service. Millions search for love on one of the 8000 online dating services (Hatfield, 2016). In 2015, 27 percent of 18- to 24-year-old Americans tried an online dating service or mobile dating app (Smith, 2016).

Online matchmaking definitely expands the pool of potential mates (Finkel et al., 2012a,b). But how effective is the matchmaking? Compared with those formed in person, Internet-formed friendships and romantic relationships are, on average, slightly more likely to last and be satisfying (Bargh & McKenna, 2004; Cacioppo et al., 2013). In one study, people disclosed more, with less posturing, to those whom they met online (McKenna et al., 2002). When conversing online with someone for 20 minutes, they felt more liking for that person than they did for someone they had met and talked with face-to-face. This was true even when (unknown to them) it was the same person! Internet friendships often feel as real and important as in-person relationships.

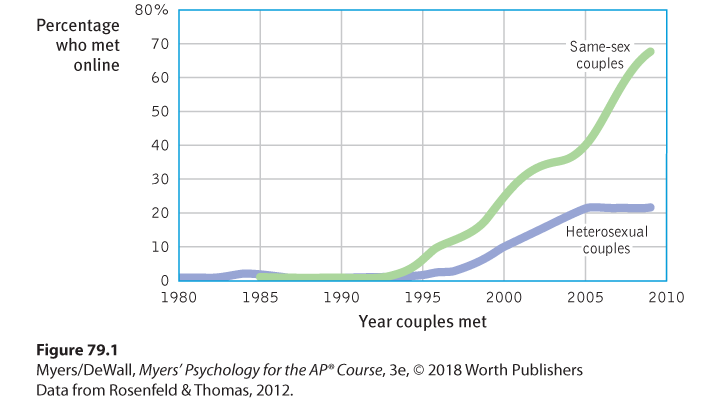

Small wonder that one survey found a leading online matchmaker enabling more than 500 U.S. marriages a day (Harris Interactive, 2010). By one estimate, online dating now is responsible for about a fifth of U.S. marriages (Crosier et al., 2012). And in a national survey of straight and gay/lesbian couples, nearly a quarter of heterosexual couples and some two-thirds of same-sex couples met online (Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012; see Figure 79.1).

Figure 79.1 Percentage of heterosexual and same-sex couples who met online

Speed dating pushes the search for romance into high gear. In a process pioneered by a matchmaking Jewish rabbi, people meet a succession of prospective partners, either in person or via webcam (Bower, 2009). After a 3- to 8-minute conversation, people move on to the next prospect. (In an in-person heterosexual meeting, one group—usually the women—remains seated while the other group circulates.) Those who want to meet again can arrange for future contact. For many participants, 4 minutes is enough time to form a feeling about a conversational partner and to register whether the partner likes them (Eastwick & Finkel, 2008a,b).

For researchers, speed dating offers a unique opportunity for studying influences on our first impressions of potential romantic partners. Some recent findings:

- People who fear rejection often elicit rejection. After a 3-minute speed date, those who most feared rejection were least often selected for a follow-up date (McClure & Lydon, 2014).

- Given more options, people make more superficial choices. When people meet lots of potential partners, they focus on more easily assessed characteristics, such as height and weight (Lenton & Francesconi, 2010).

- Men wish for future contact with more of their speed dates; women tend to be choosier. But this difference disappears if the conventional roles are reversed, so that men stay seated while women circulate (Finkel & Eastwick, 2009).

Physical Attractiveness

Once proximity affords us contact, what most affects our first impressions? The person’s sincerity? Intelligence? Personality? Hundreds of experiments reveal that it is something more superficial: physical appearance. This finding is unnerving for those of us taught that “beauty is only skin deep” and “appearances can be deceiving.”

In one early study, researchers randomly matched new University of Minnesota students for a Welcome Week dance (Walster et al., 1966). Before the dance, the researchers gave each student a battery of personality and aptitude tests, and they rated each student’s physical attractiveness. During the blind date, the couples danced and talked for more than two hours and then took a brief intermission to rate their dates. What predicted whether they liked each other? Only one thing: appearance. Both the men and the women liked good-looking dates best. Women are more likely than men to say that another’s looks don’t affect them (Lippa, 2007). But studies show that a man’s looks do affect women’s behavior (Eastwick et al., 2014a,b). In speed-dating experiments, attractiveness influences first impressions for both sexes (Belot & Francesconi, 2006; Finkel & Eastwick, 2008).

Physical attractiveness also predicts how often people date and how popular they feel. And it affects initial impressions of people’s personalities. We don’t assume that attractive people are more compassionate, but we do perceive them as healthier, happier, more sensitive, more successful, and more socially skilled (Eagly et al., 1991; Feingold, 1992; Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986).

For those of us who find the importance of looks unfair and unenlightened, three other findings may be reassuring.

- People’s attractiveness is surprisingly unrelated to their self-esteem and happiness (Diener et al., 1995; Major et al., 1984). Unless we have just compared ourselves with superattractive people, few of us (thanks, perhaps, to the mere exposure effect) view ourselves as unattractive (Thornton & Moore, 1993).

- Strikingly attractive people are sometimes suspicious that praise for their work may simply be a reaction to their looks. Less attractive people have been more likely to accept praise as sincere (Berscheid, 1981).

- For couples who were friends before lovers—who became romantically involved long after first meeting—looks matter less (Hunt et al., 2015). With slow-cooked love, shared values and interests matter more.

Beauty is also in the eye of the culture. Hoping to look attractive, people across the globe have pierced and tattooed their bodies, lengthened their necks, bound their feet, and artificially lightened or darkened their skin and hair. They have gorged themselves to achieve a full figure or liposuctioned fat to achieve a slim one, applied chemicals to rid themselves of unwanted hair or to regrow wanted hair, strapped on leather garments to make their breasts seem smaller or relied on push-up bras and surgery to make them look bigger. Cultural ideals change over time. For women in North America, the ultra-thin ideal of the Roaring Twenties gave way to the soft, voluptuous Marilyn Monroe ideal of the 1950s, only to be replaced by today’s lean yet busty ideal.

In the eye of the beholder Conceptions of attractiveness vary by culture and over time. Yet some adult physical features, such as a healthy appearance and a relatively symmetrical face, seem attractive everywhere.

“Play coy if you like, but no one can resist a perfectly symmetrical face.”

Some aspects of heterosexual attractiveness, however, do cross place and time (Cunningham et al., 2005; Langlois et al., 2000). By providing reproductive clues, bodies influence sexual attraction. As evolutionary psychologists explain (Module 15), men in many cultures, from Australia to Zambia, judge women as more attractive if they have a youthful, fertile appearance, suggested by a low waist-to-hip ratio (Karremans et al., 2010; Perilloux et al., 2010; Platek & Singh, 2010). Women feel attracted to healthy-looking men, but especially—and more so when ovulating—to those who seem mature, dominant, masculine, and affluent (Gallup & Frederick, 2010; Gangestad et al., 2010).

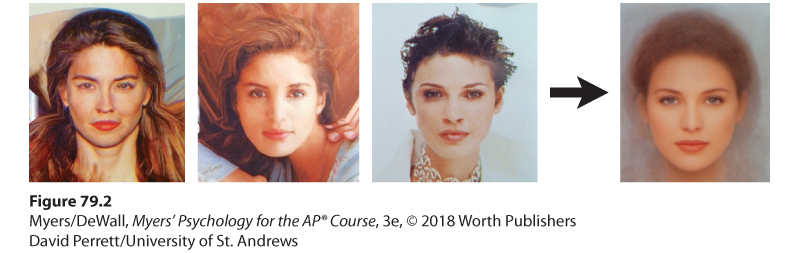

Faces matter, too. When people rate opposite-sex faces and bodies separately, the face tends to be the better predictor of overall physical attractiveness (Currie & Little, 2009; Peters et al., 2007). So what makes a face attractive? Part of the answer is features that are neither unusually large nor small. Symmetrical faces and bodies are also perceived as more sexually attractive (Rhodes et al., 1999; Singh, 1995; Thornhill & Gangestad, 1994). This helps explain why an averaged (and therefore symmetrical) face is attractive (Figure 79.2). In one clever demonstration, researchers digitized the faces of up to 32 college students and used a computer to average them (Langlois & Roggman, 1990). The result? Viewers judged the averaged, composite faces as more attractive than 96 percent of the individual faces. (If only we could merge either half of our face with its mirror image: Our symmetrical new face would be a notch more attractive.)

Figure 79.2 Average is attractive

Which of these faces offered by University of St. Andrews psychologist David Perrett (2002, 2010) is most attractive? Most people say it’s the face on the right—of a nonexistent person that is the average composite of these 3 plus 57 other actual faces.

Our feelings also influence our attractiveness judgments. Imagine two people: One is honest, humorous, and polite. The other is rude, unfair, and abusive. Which one is more attractive? Most people perceive the person with the appealing traits as more physically attractive (Lewandowski et al., 2007). Or imagine being paired with a stranger of the sex you find attractive—someone who listens intently to your self-disclosures. Might you feel a twinge of sexual attraction toward that empathic person? Student volunteers did, in several experiments (Birnbaum & Reis, 2012). Our feelings influence our perceptions. Those we like we find attractive.

In a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, Prince Charming asks Cinderella, “Do I love you because you’re beautiful, or are you beautiful because I love you?” Chances are it’s both. As we see our loved ones again and again, their physical imperfections grow less noticeable and their attractiveness grows more apparent (Beaman & Klentz, 1983; Gross & Crofton, 1977). Shakespeare said it in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind.” Come to love someone and watch beauty grow. Love sees loveliness.

Similarity

So proximity has brought you into contact with someone, and your appearance has made an acceptable first impression. What influences whether you will become friends? As you get to know each other, will the chemistry be better if you are opposites or if you are alike?

Extreme makeover In affluent, beauty-conscious cultures, increasing numbers of people, such as reality TV star Kylie Jenner, have turned to cosmetic procedures to change their looks.

It makes a good story—extremely different types liking or loving each other: Rat, Mole, and Badger in The Wind in the Willows, Frog and Toad in Arnold Lobel’s books, Edward and Bella in the Twilight series. The stories delight us by expressing what we seldom experience. In real life, opposites retract (Rosenbaum, 1986; Montoya & Horton, 2013). Compared with randomly paired people, friends and couples are far more likely to share common attitudes, beliefs, and interests (and, for that matter, age, religion, race, education, intelligence, smoking behavior, and economic status). Moreover, the more alike people are, the more their liking endures (Byrne, 1971; Hartl et al., 2015). Journalist Walter Lippmann was right to suppose that love lasts “when the lovers love many things together, and not merely each other.” Similarity breeds content.

“ I like the Pope unless the Pope doesn’t like me. Then I don’t like the Pope.”

Donald Trump, February 18, 2016

Similarity attracts; perceived dissimilarity does not.

Proximity, attractiveness, and similarity are not the only determinants of attraction. We also like those who like us. This is especially true when our self-image is low. When we believe someone likes us, we feel good and respond to them warmly, which leads them to like us even more (Curtis & Miller, 1986). To be liked is powerfully rewarding.

Indeed, all the findings we have considered so far can be explained by a simple reward theory of attraction: We will like those whose behavior is rewarding to us, including those who are both able and willing to help us achieve our goals (Montoya & Horton, 2014). When people live or work in close proximity to us, it requires less time and effort to develop the friendship and enjoy its benefits. When people are attractive, they are aesthetically pleasing, and associating with them can be socially rewarding. When people share our views, they reward us by validating our beliefs.