As I have suggested above, tennis is a ‘style’ of human motion, and is distinguished from general motion by its own rules. However, there are also individually ‘stylish’ players. The same is true of literature. It is distinguished from general vocal or written expression by those ways of operating or of being regarded that are peculiar to the literary game. Yet there are also individual styles of writing.

From the beginnings of literary analysis as we know it, in Greece, these two sorts of analysis of stylistic perceptions – distinguishing activities and distinguishing individuals: public and private styles – have woven in and out of each other. The Greeks were well aware of the distinction between content and style, but their attitude towards these familiar abstractions were not quite ours. Rhetoricians from Plato and Aristotle to Protagoras and Demetrius distinguished dianoia or pragmata (‘thought’ or ‘facts’) from lexis and taxis (‘word-choice’ or ‘arrangement’). They expertly distinguished the characteristic lexical and tactical configurations of Demosthenes and Sophocles among others, not descriptively, in order to differentiate between them as individual creators, but prescriptively, to set out the rules of style. It almost seems as if Demosthenes’ individual peculiarities of style were seen not as personal tics but counted as ways of playing the ‘oratory game’ which others had better learn. The style of Demosthenes was not his personal or distinctive brand of speaking but the way to be an orator – a Platonic ideal of the orator revealing itself in gleams of Style through the individual activity of Demosthenes. In our day the closest parallel to this way of interpreting personal style as public tenet can be found in chess. The ‘personal’ idiosyncrasies of Morphy, Steinitz, Tarrasch, Niem-zovitch, Capablanca, Alekhine and others turn out to be ways of playing the game that the game itself requires. It is the notion ‘oratory’ or the notion ‘chess’ that becomes clearer, not the notion ‘Demosthenes’ or the notion ‘Niem-zovitch’.

The idea of a public game – the revealing of ‘oratory’, ‘tragedy’, ‘comedy’, ‘history’, through the activity and peculiarities of its practitioners – soon gave way to the notion of privacy familiar to the Romantics and to us, namely, that of the utterly private idiosyncrasies of individuals. There seems to have been a retreat inwards accompanying the conquest of Greece by the Macedonians. The fourth-century Hellenistic poet Callimachus wrote: ‘I hate the cycle poems [epics], and view with no joy a road which carries many men here and there … All public things disgust me.’ Under the Macedonians in Greece and, later on, in Rome under the decaying Republic and the Empire, the public games of statehood were being played for the citizens, not by them. The experts in statecraft took over from ordinary people, and public participation in government gave way to government as a ‘spectator sport’, with an audience watching the heroes of civil war and military anarchy battle it out. The nature of the game itself was settled by impersonal ‘professional’ authority. Style was to become the sum of the ways in which an individual player might play it. The Roman distinction between facta and stilus, things and the style of things, what and how, is partly the distinction of the individual reactions of human beings under pressure, when all that human beings have in common are their differences. (The official Roman ‘line’ emphasized the collective, but the modern reader can recognize the presence of individual styles in the great Roman creators.)

Since that time stylistic study has had two main objectives: to describe the nature of both the public games of style and of private styles.

The first concern, the study of the public games of literature, leads the critic to try to describe how literary creators employ the linguistic codes they and their hearers and readers possess completely or partially in common. The emphasis here is on similarities of code, not differences; therefore, the effects described reside potentially in the standard language. Here, on the Greek model mentioned above, it is ‘literature’ that is becoming clearer, not ‘writers’.

The second concern is not with the potentialities of a public, collective norm of language at all but with the description of private styles, with the reasons for a reader's intuition of individual personality in literary and other stretches of utterance. This approach pursues style to its last division, to the centre of personality itself, and is, therefore, rather more along the line of the Roman model above, an examination of an intensely private deployment of linguistic possibilities.

Let us begin with the public game, and its most ‘public’ aspect. A literary creator makes use of all the components of the linguistic apparatus that he and his audience possess in common. This may include a private stylistic component (everybody has one), but it certainly includes all of the ‘public’ components of language. They involve phonology – the poet and the audience share sound-systems and systems of intonation – and syntax. To say this is to say only that the poet and his audience speak the same language.

Poets use the characteristic motions used for the pronunciation of sounds for artistic purposes. We can all feel that the tongue lies at the bottom of the mouth in the pronunciation of ‘aw!’ and ‘ah!’ and humps itself up higher and higher in ‘ed’, ‘ad’, and ‘id’. In ‘id’ the tension is considerable, and can be augmented by a forced smiling, a stretching of the lips. If we are carefully performing a line (of poetry or not) in which the stressed syllables range from ‘aw’ to ‘id’, we can be made to force the tongue higher and higher, and more and more forward in the buccal cavity of the mouth, and to force the lips wider and wider apart:

AW |

AH |

ED |

AD |

ID |

Or |

far |

events |

add |

interest. |

The movements of the tongue here do not add anything to the appreciation of the sentence, since the sense of the sentence has nothing to do (except vaguely) with ‘moving upward’. In a sentence like the following, perhaps inserted in a poem about climbing a hill, the movement of the stressed vowels does have a descriptive (or mimetic) value:

AW |

AH |

ED |

AD |

ID |

Sorely |

tried, |

everybody clambered to the tip |

||

(Note that the ‘tried’ begins its vowel sounds with ‘ah’ before moving to ‘ee’.)

Poets have been aware of the possibilities of reinforcing meaning with sound ever since Homer (and probably before). It has always seemed an added grace of style (onomatopoeia) when the sound seems an echo to the sense. But what actually happens in these cases?

Let us have a closer look at some lines in which the poets ‘force’ an articulation pattern on the reader as part of their public stylistic repertoire.

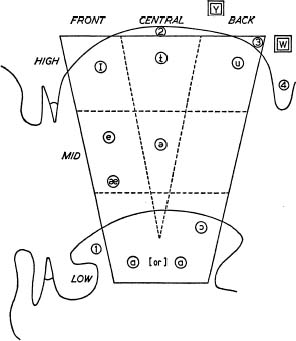

figure 1: The buccal cavity or interior of the mouth (seen from the side) and possible positions of the vowels and glides (Standard American [E. L. Epstein])

1. Tongue

2. Hard palate (‘y’ glide)

3. Soft palate (‘velum’) (‘w’ glide)

4. Uvula

High-front: ‘I’ as in ‘bit’ or ‘id’ |

Low-back: ‘ɔ’ as in ‘bought’ or ‘horse’ or ‘aw’ |

Mid-front: ‘e’ as in ‘bet’ or ‘bear’ or ‘ed’; ‘æ’ as in ‘bat’ or ‘ad’ |

High-back: ‘u’ as in ‘put’ or ‘good’ |

Low-front: ‘a’ as in ‘pot’ or ‘bog’ |

Mid-central: ‘ə’ as in ‘butt’ |

or Low-back or'ah!’ |

High-central: ‘i’ as in ‘church’ |

Note: This chart represents a compromise and simplification of many systems, and is based upon a description of Standard American Speech in G. L. Trager, and H. L. Smith, Jr., An Outline of English Structure, Norman, Oklahoma, 1951. Some systems place ‘æ’ as low and ‘d’ as mid.

(a) [Weep no more, woeful shepherds, weep no more, For Lycidas, your sorrow, is not dead,] Sunk though he be beneath the watry floor.

(Milton, Lycidas)

(b) A lonely impulse of delight Drove to this tumult in the clouds

(Yeats, An Irish Airman)

(c) The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation

(Hopkins, To R. B.)

(d) A bracelet of bright hair about the bone.

(Donne, The Relic)

(e) The fine delight that fathers thought.

(Hopkins, To R.B.)

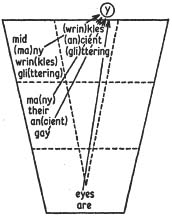

(f) Accomplished fingers begin to play. Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes, Their ancient, glittering eyes, are gay.

(Yeats, Lapis Lazuli)

Selections (a), (b), and perhaps (c) seem to refer to actual movements in space. Selections (d) and (e) seem to display a metaphorical, emotional ‘movement’, while selection (f) sustains a certain feeling of buoyancy. It is possible that the sound-structure of the lines (specifically, the pattern derived from comparing the stressed vowels of each line), either reinforces or produces the effects referred to (see figure I).

In pronouncing the stressed vowels in selection (a). ‘Sunk though he be beneath the watry floor’, the tongue-muscle mimes a movement from low-mid to high-front to low-back in the mouth, as any reader can feel for himself by observing the movements of the tongue:

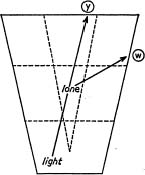

figure 2: Vowel positions in the line from Lycidas

The ‘buccal dance’, as the French critic André Spire calls it, reinforces the meaning of line (a); the surface of the sea seems to be mimed by the high-front vowels (‘be’, ‘beneath’), and the vowels placed between low or low-back stressed vowels (‘sunk’, ‘watry’, ‘floor’), seem to convey a notion of the bottom of the sea. Of course, it cannot be said too often that content always precedes pronunciation; as Pope insisted, the sound must seem an echo to the sense.*

In selection (b), ‘A lonely impulse of delight’, the situation is less directly mimed. In the lines from Lycidas the stressed vowels in ‘sunk’ and ‘watry floor’ are actually below the points of articulation for ‘be’ and ‘-neath’. The first and last vowels stressed in the lines from An Irish Airman – ‘lone-’ and ‘-light’ – demand a tongue-movement from low to high (miming the aeroplane climbing) using a more complex pattern which involves diphthongs (see figure 3):

As the reader can feel, the vowel material in ‘lone-’ begins with a mid-central vowel and glides to a sound pronounced in the same place and in approximately the same way as the sound ‘w’, that is, with the back of the tongue pressed against the back of the mouth (the soft palate, or velum), and the lips pursed. The material in ‘-light’ begins lower and (perhaps) further back in the mouth than the vowel in ‘lone-’, but glides to a sound articulated like ‘y’, with the tongue pressed against the hard palate, at a point in front, and slightly above, the point of velar articulation for the ‘w’ glide; here the lips are stretched in a smile:

figure 3: The stressed vowels beginning and ending the line from Yeats's Irish Airman

lone- |

-light |

(ordinary spelling) |

‘ləwn’ |

‘layt’ |

(phonemic notation) |

velar glide |

palatal glide |

|

Although the point of articulation for ‘y’ is slightly higher than that of ‘w’, it seems to be the movement forward in the point of articulation, from the soft palate to the hard palate, that symbolizes the movement upward of the aeroplane. Perhaps, paradoxically, the greater distance in the movement required to produce ‘-light’ than to produce ‘lone-’, a movement beginning at a lower point, also helps to produce a subjective impression in the reader of an upward movement. (Robert Frost performs the same movement, with the same effect, in his line ‘The road at the top of the rise’ in The Middleness of the Road.)

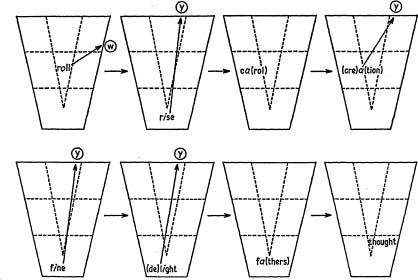

In the selection (c), ‘The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation’, the vowel material in ‘roll’ and ‘rise’ is the same as in ‘lone-’ and ‘-light’, with the same subjective effect. (Note also the alliteration in these lines.) The greater rise from ‘roll’ and ‘rise’ to ‘carol’ and ‘creation’ derives partly from the actual difference in height of the vowels, and partly from a movement forward; both ‘ə’ and ‘a’ are low or central in the mouth (mid-central and low-front/back), while the stressed vowels in ‘carol’ and ‘creation’ are further forward or actually higher (low-front and mid-front – gliding to the hard palate). The glides outline two separate patterns of ‘upward’ (forward) movement, while the vowels ‘recoil’ and then move steadily forward and upward, for a single expressive curve:

roll |

rise |

ca(rol) |

(cre)a(tion) |

|||

vowels: mid-central→low-front/back→mid-front |

||||||

(rise expressed) |

||||||

glides: |

velar→palatal→none→palatal |

|||

Note also that in ‘creation’, the vowel material of the weakly stressed first syllable nevertheless possesses a ‘Iy’ articulation, ending on the hard palate, which is then repeated for the following, stressed, syllable, ‘kriyéyšin’. The complex buccal dance of the tongue journeying swiftly upward and forward to articulate the line mimes the content of the line, the metaphorical downward roll and upward rise, perhaps miming the skylark of the poet's thought. (Again, however, if the line expressed a different idea than that of upward expanding movement, such a sound pattern as the above would be irrelevant, if not actually contradictory; content is logically and psychologically primary.) (See figure 4.)

In selection (e), ‘The fine delight that fathers thought’, ‘fine’ and ‘delight’ glide to a ‘bright’ (i.e. forward) palatal articulation; then the line becomes grave with the low or mid-back, glideless vowels of ‘fathers’ and ‘thought’): ay, ay, a, ɔ. Indeed, Hopkins may have pronounced ‘thought’ as ‘ɔat’ rather than ‘θɔt’, so all four stressed vowels would be the same, ‘a’; the effect of the line would depend upon the pensive mood which is evoked when the low vowel, ‘a’, is deprived of its ‘bright’ glide, ‘y’.

In addition to the dance of the tongue muscle, the actual or potential movements of the lips in the physical or mental articulation of a poetic line frequently provides significant dramatic reinforcement of the effect of the line's meaning. The pronunciation of front vowels in English is often assisted by a ‘smiling’ (unrounded) motion of the lips (‘bit’, ‘bet’, ‘bat’), while vowels like ‘u’ in ‘put’, and the velar glide ‘w’ sometimes require a pursing or rounding of the lips. In effect, a poet frequently forces you to smile or frown when you pronounce his lines. Donne does, in selection (d), ‘A bracelet of bright hair about the bone’, for two of the first three stressed syllables. The simple vowels (apart from glides) in ‘brace-’ and ‘hair’ are both front vowels (in my pronunciation almost the same vowel, ‘e’, as in ‘pet’), and both force me to smile. The glides in ‘brace-’ and ‘bright’ are both the high, hard-palate glide ‘y’, so by the combination of front vowels and front glides, the first three stressed syllables are all ‘bright’ (i.e. forward) in articulatory movement. Then ‘bone’ alters everything; a mid-central vowel gliding to the velum (with a pursing of the lips) switches off the light. Here there is no actual movement expressed in the content, either that of the mind's eye in Lycidas seeking Edward King beneath the surface of the Irish Sea, or of an airman or skylark-poet rising to a height. The ‘movement’ is essentially metaphorical, a sudden sinking of the spirit from the smiling notions of ‘bracelet’ and ‘bright hair’ to the grimness of’ bone’.

figure 4: The vowel movement in the Hopkins lines from To R. B.

figure 5: The stressed vowels in Donne's line ‘a bracelet of bright hair about the bone’

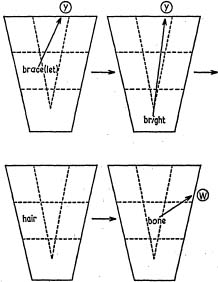

When the poet forces the reader physically to smile or look grave, the appropriate emotion is also often evoked or reinforced. In the lines from Lapis Lazuli, Yeats conveys the ‘gaiety’ of the disciplined attitude to tragedies (the theme of the poem) by the buccal dance of the stressed syllables (in my pronunciation):

accomplished |

a |

wrinkles |

I |

fingers |

I |

eyes |

ay |

begin |

I |

ancient |

ey |

play |

ey |

glittering |

I |

eyes |

ay |

eyes |

ay |

many |

e |

gay |

ey |

With the exception of the low vowels in ‘-com-’ and in ‘eyes’, every stressed vowel either is or contains a high- or mid-front vowel (‘I’ or ‘e’); even the apparent exception, ‘ay’ in ‘eyes’, may originate in a low-front vowel and then glide up to the hard palate, as ‘ay’. Many of the unstressed syllables are also high- or mid-front: ‘accomplished’, ‘fingers’, ‘begin’, ‘their’, ‘mid’, ‘many’, ‘wrinkles’, ‘ancient’, ‘glittering’ (see figure 6). There is, therefore, a generally ‘bright’, high tone, accompanied by almost constant smiling, a steady gaiety.

figure 6: The vowels in lines 54–6 of Lapis Lazuli (Yeats). Note that all stressed vowels, and almost all unstressed ones, are front vowels or eventuate in the high glide, ‘y’; most, in fact, are high- and mid-front.

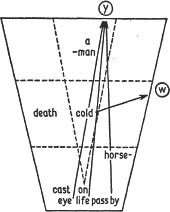

This is not an accident; Yeats when he wishes can orchestrate vowels in an entirely different area, for an entirely different effect. Consider his deployment of low vowels in his own epitaph:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death,

Horseman, pass by.

The vowel in the word ‘eye’ here fits into a trio of lines that contain no high-front vowels at all, and in which most are very low. It looks as if Yeats, by emphasizing or avoiding buccal areas, could control vowel register with great sensitivity for the strong emotional reinforcement of content.

figure 7: The vowels in Yeats's epitaph (in my pronunciation

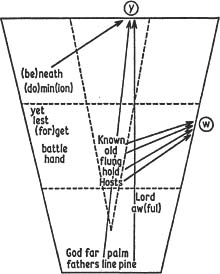

Sometimes an entire poem features mainly low or mid vowels, as in Yeats's epitaph, for a mimesis of impressive ‘chest’ speech. Kipling's Recessional is such a poem. The first stanza shows the tongue sunk on the floor of the mouth, or only rising part way, thus allowing a resonance to be projected from the chest. Note that the only high stressed vowel occurs in ‘dominion’ (and possibly in ‘beneath – if that is a stressed vowel):

God of our fathers, known of old,

Lord of the far-flung battle-line,

Beneath whose awful hand we hold

Lord God of hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget, lest we forget!

This pattern (see figure 8) is sustained throughout the poem, the only prominent exception being the contrast at ‘reeking tube’ – the vocal trace of the hysterical pride of the enemy, perhaps.*

Once this type of vocal orchestration is mastered, a poet in control of his craft can write (or rewrite) a sonorous poem of this sort with considerable assurance that it will succeed in its effect. Indeed, the opposite effect can be obtained by avoiding these low and mid vowels. It is almost as if our emotions are reactions to what our body is doing, as in the well-known theory of emotion associated with William James: ‘I am weeping, therefore I must be unhappy.’ The reader's version of this theory would be: ‘I am pronouncing deep, sonorous sounds, therefore I must be in deadly earnest.’

figure 8: The stressed vowels in the first stanza of Kipling's Recessional

We have now seen reinforcement of content by buccal miming in several lines. However, buccal movement is by no means always directly mimetic. It may be purely ornamental. Tennyson, for example, seems to delight in abstract buccal exercises, as in Tithonus:

The woods decay, the woods decay and fall.

The vapours weep their burthen to the ground.

Man comes and tills the field and lies beneath,

And after many a summer dies the swan.

Me only cruel immortality

Consumes; I wither slowly in thine arms,

Here at the quiet limit of the world,

A white-haired shadow, roaming like a dream,

The ever-silent spaces of the East,

Far-folded mists and gleaming halls of morn.

There seems to be little echoing of content here, except perhaps in the sixth and seventh lines, and in ‘fall’ and ‘burthen’. On the contrary, the vowel patterning seems to operate on its own, and even tends to de-emphasize the specific message. It is almost as if Tennyson were more interested in his own vocal apparatus than in his themes – a suspicion that many critics have voiced.

The above analysis has treated only one aspect of phonology, and that in only one way. The descriptions of sounds have emphasized their actually present or mentally envisaged methods of production (‘articulation’). The description of effects produced by syllable articulation is, however, only the beginning of a description of the styles of language in the literature game. The articulatory pattern for the pronunciation of syllables is frequently overridden by an intona-tional pattern, one that provides possible pronunciations for sentences and discourses, and which is only indirectly linked to a syllable-by-syllable schematic analysis.

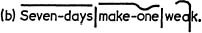

There is no more confused or controversial area in linguistics than the description of intonation (or ‘prosody’, as it is frequently termed by British linguists). The phenomenon of intonation is obvious enough; with careful pronunciation it indicates the difference between these two sentences:

(a) Seven days make one week.

(b) Seven days make one weak.

Intonation seems to be a matter of pitch, of pauses, and of varying stress on syllables. (From here on, internal pauses in the sentence will be indicated by vertical lines (|); the straight or curved lines above the sentence indicate the movement of the pitch intonation.) For example, sentence

(a) could reasonably be intoned:

Sentence (b) could be intoned:

If sentence (a), which seems to mean ‘a week is made up of seven days’, were to be intoned in sentence (b)’s pattern, it would sound bizarre: the speaker would seem to be hesitating and then speeding ahead, as if under the influence of strong emotion. If sentence (b), which seems to mean ‘seven days [of dissipation] leave the reveller in a debilitated condition’, were intoned like sentence (a), it would seem even stranger; perhaps the entire meaning would be lost.

The intonational situation, however, is not at all as clear-cut and obvious as these examples would suggest. Sentences (a) and (b) are ‘segmentally homophonic’; that is, intonation apart, they contain the same sounds in the same order (or similar sounds: weaker stress often alters vowel quality). Yet most sentences in casual discourse are not ambiguous in the ways these sentences are. Even if they were, there is a good chance that the distinction between them would not be due to clear intonation; most people would simply rely upon context to resolve the ambiguity. As we will see, intonation is to a certain (or uncertain) extent unnecessary for meaning. The function of intonation seems to be to reinforce syntactic and semantic guesses already entertained by the listener to such utterances, rather than to signal the primary information to the listener, as to an entirely passive recipient.

This realization has caused a complete alteration in the study of modern phonology. To those linguists who believe that listeners are mere passive recipients of sets of acoustic signals which bear all the necessary information for their decoding and interpretation, this sloppiness of normal in-tonational standards is highly distressing and has led to considerable hypothesizing that has not stood up very well to objective testing. In one test, two linguists have made widely varying transcriptions of the same utterances, many of their markings corresponding to no part of the actual acoustic events, as measured by a recording machine. This has led one diligent investigator of intonational phenomena, Philip Lieberman, to conclude that ‘competent linguists do not consider simply the physically present acoustic signal’ when they transcribe the intonational phenomena that they think they have heard.1 Lieberman suggests a more complex hypothesis:

The listener mentally constructs a phonetic signal that incorporates both the distinctive features that are uniquely categorized by the acoustic signal and those that he hypothesized in order to arrive at a reasonable syntactic and semantic interpretation of the message. In some instances the acoustic signal may be both necessary and sufficient to specify uniquely the phonetic elements of the message. This usually occurs when a talker is asked to read aloud nonsense syllables or isolated words. The talker, of course, ‘knows’ that the message will not allow the listener to test any reasonably complex phonetic hypotheses. The speaker therefore carefully articulates the message.

The speaker's decisions on the relative precision with which he must specify the phonetic elements of the message in the acoustic signal must be made in some interpretive component of the grammar. The speaker must weigh the anticipated linguistic competence of the hearer as well as the linguistic context furnished by the entire sentence, the semantic context of the social situation … The listener's process of phonetic hypothesis formation also takes place in this interpretive component…2

While this hypothesis may explain the comparative lack of intonational structures in the acoustic texture of casual conversation, the situation appears to be different for the silent reader of poetry. Here the speaker is his own listener, and there is some evidence that externally or internally articulated intonation in such a situation conventionally acquires a crystalline perfection rare in less limited contexts. This perfection is described by Martin Joos, in The Five Clocks, as a feature of ‘formal style’:

Lacking all personal support, the text must fight its own battles … Robbed of personal links to reality … it endeavours to employ only logical links … The pronunciation [intonation] is explicit to the point of clattering …3

This formal style applies to the silent reading of poetry, since here indeed ‘the text must fight its own battles’. In addition, normally unnecessary intonational devices (stress, pitch, juncture) are not unnecessary in the performance of literary artefacts, since such specifically literary phenomena as metre, rhythm, cesura, balance, rhetorical emphasis and the like may and normally do depend upon a ‘clatteringly explicit’ performance.

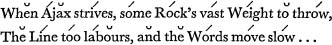

Pope provides an excellent example of the extent to which poets rely upon their readers’ sense of ‘formal style’ to intone their poems adequately (more adequately, in many cases, than the poets themselves, who tend to be wretched performers of their own work; after all, it is old stuff to them!). In An Essay on Criticism (1711), there is a famous poetic jeu d'esprit, a series of more than four dozen lines (lines 337–93) on the errors of Pope's contemporaries and his prescriptions for improvement. In these lines he defines faults and virtues, demonstrating them at the same time with what the eighteenth century called ‘representative metre’ (imitative effects). Although these lines are a mine for the linguistic critic, a magnificent example of playing the public literature game, I propose to analyse only one couplet, a famous one:

When Ajax strives, some Rock's vast Weight to throw,

The Line too labours, and the Words move slow …

There is no doubt here as to Pope's intentions – the effect has been clear to more than two hundred and sixty years of readers. Pope himself wrote:’… a good Poet will adapt the very Sounds, as well as Words, to the Things he treats of. So that there is (if one may express it so) a Style of Sound …’ As we shall see, the ‘Style of Sound’ Pope describes involves more than the individual sounds themselves (the ‘segmental phonemes’), and their transitional peculiarities. The more important effects are conveyed by the intonational phenomena forced upon the reader by the poet, and as Pope says in the same letter: ‘This … is undoubtedly of wonderful force in imprinting the image on the reader.’4

The slow tempo and ‘obstruction’ in the reading of the Ajax lines are obviously meant by Pope to mime the difficulty of the feat described, the manipulation of a huge rock by the Grecian warrior, as, for example, in Book XII, line 383, of the Iliad.*

The Ajax lines have often been analysed, but the sources of the effect of obstruction and difficulty obvious to the reader have never been completely or precisely described. It turns out that an adequate description requires a theory of articulation and intonation which is only now in the process of formulation, and is the subject of fierce debate. However, there are a few immediately discernible causes of these effects. For instance, there is what seems to be the substitution of spondees (two strong stresses) for iambic feet (one weak followed by one strong stress) in the third and fourth feet in the first line, and for the second and fifth feet in the second line (to compensate, pyrrhic feet – two weak stresses – are substituted for the third foot of the second line):

Yet to refer the obstruction to spondees and pyrrhic feet is to appeal from one mystery to another, for we may well ask why we are forced to pronounce the obstructive spondees and pyrrhic feet where they occur, and how do we know that they are occurring?

It is first necessary to dismiss the notion that the obstructive effect of the Ajax lines is caused by the number of sounds in them that are ‘hard to pronounce’. All of the individual sounds in the line are English sounds, and therefore there are none that should offer an English-speaker the slightest difficulty. Nor are they assembled into unorthodox syllabic patterns; every syllable in both lines conforms to the canonical pattern for English syllables.

A more advanced analysis might focus on a possible excess of consonant clusters and ‘complex nuclei’ (‘long vowels’, that is, a vowel plus a ‘y’ or ‘w’ glide), as a source for a sense of excess work done, or anticipated mentally, in pronunciation. It is possible that some lines of poetry might derive some of their stylistic effects from such a source, as, for example, Ben Jonson's line: ‘Slow, slow, fresh fount, keep time with my salt tears.’ In this line every syllable (with the exception of ‘with’) contains either a consonant cluster, or a complex nucleus; ‘slow’, ‘fount’, and ‘tears’ contain both. Yet even this line derives its major obstructive effects from other sources; its intonational obstructions are based, finally, on syntactic complexity.

In the Ajax lines of Pope, there are indeed syllables that contain either double or triple consonant clusters or complex nuclei, or both: the two syllables of ‘Ajax’ (however pronounced), ‘strives’, ‘Rock's’, ‘vast’, ‘Weight’, ‘throw’, ‘Line’, ‘too’, both syllables of ‘labours’, ‘and’, ‘Words’, ‘move’, ‘slow’. This makes a total of fifteen out of twenty syllables, or almost as high an average as the Ben Jonson lines. It is also higher than the average for Pope's ‘neutral’ lines, as, for example, in lines 1–91 of An Essay, where an average line contains no more than two or three consonant clusters and three complex nuclei. The Ajax lines contain from four to six consonant clusters each, and five or six complex nuclei. Therefore it is possible to say, at least tentatively, that some of the sense of obstruction derives from an excess of phonic material to be articulated.

Much more obstructive, however, is the difficulty of transition from one syllable to the next in the first Ajax line. In three places – ‘Ajax-strives’, ‘strives-some’, ‘weight-to’ – the same or similar sounds end one syllable and begin the next. Normally (that is, in casual discourse), there would be no problem; the first of the similar sounds would be omitted, by a variety of elision. So, if the first Ajax line were a line from casual conversation, it might sound something like, ‘When Ajak’ strive’ some Rock's vast Weigh’ to throw.’

It is proof of the existence and the power of the ‘formal style’ of poetry reading, even in silent reading, that this elision does not operate here. Elision of this sort is not part of the way to perform in formal style, which is why Joos refers to a ‘clattering’ explicitness of pronunciation in his description. To pronounce both of the transitional border consonants, as in ‘Ajax-strives’, without elision requires a pause, an actual ‘cessation of phonation’. This cessation, occurring three times in a short line, provides a major source for the feeling of obstruction: Ajax/strives, strives/some, weight/to. It is also proof of the operation of some other mode of performance than that of casual speech in the presence of poetry, one that Pope relies upon for part of his imitative effect, and with success: ten generations of readers have felt this obstruction. The cancellation of this elision in formal style seems to be the effect of a reader's socially inherited competence in the reading of poetry, and is therefore a ‘normal’ or, in this context, ‘public’ performance of a special sort of discourse.

Pope employs this technique with even more boldness in another ‘representative’ line from this section:

And ten low Words oft creep in one dull line.

(1.347)

Here there is cancellation of elision, of one degree or another, in six places: and-ten, ten-low, low-Words, oft-creep, one-dull, dull-line. ‘Ten-low’ and ‘one-dull’ exhibit a cancellation of a lesser degree of elision, since the pairs /n/ and /I/, and /n/ and /d/, though not the same sounds, are too close in point of articulation (the tongue behind the teeth) to be pronounced in a formal style without a cessation of phonation, almost as if they were in danger of suffering elision. In a related phenomenon, the transitions ‘words-oft’ and ‘creep-in’ are too ‘easy’ for formal style; without a cessation of phonation, the pairs could sound like ‘word-zoft’ and ‘cree-pin’. In this line, therefore, Pope deliberately sows difficulties in every transition, which is one of the reasons it is so ‘dull’, that is, ‘obstructed’.

However, the main sources for the effect of obstruction in the Ajax lines are not to be found in the individual sounds, or their clustering, or their transition as such; they derive from intonational difficulties, articulations of a pattern which extends over larger stretches of the discourse than the sound, the syllable, or the syllable boundary. The second Ajax line, ‘The Line too labours, and the Words move slow’, is unlike the first in that it exhibits no transitional problems at all, and yet it seems more difficult to say than the first.

Two types of intonational description are required to describe these lines adequately enough so that the major sources of their obstruction can be clearly discerned: syllable-stress, and pitch and junctural patterning.5

Every syllable in English has as its core a vowel (simple or complex); each syllable is characterized by a prominence, a special effort of articulation, generally centring on its vowel, which has been interpreted as a ‘stress’. Exactly what stress is is still the subject of debate, as is the question of the number of the ‘degrees’ of stress, and whether these degrees have any absolute value. However, it is obvious that in English some syllables seem to be pronounced with more force than others. In most lines of poetry the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is clear: ‘When Ajax strives, some Rock's vast Weight to throw’ (‘some’ should perhaps be unstressed, or less stressed). There is a pattern in stressing; only words from certain syntactic classes are entitled to a stress prominence: nouns, most verbs (not to be or to become, or other ‘equational’ verbs), adjectives (as strictly defined – not words like ‘very’ or ‘the’), adverbs and adverbials, and some others. This assignment of stress in English according to word class seems to be based upon the information structure of the discourse; the words bearing the highest degree of new information also bear the highest stress. When new information becomes old information in a discourse, the stress is lost, as in pronouns: John left, but he came back. ‘He’ has no stress prominence here because it bears no new information.

Other syllables that have little stress prominence are those in polysyllabic words, unless these words are made up of shorter content-words; ‘operator’ and ‘elevator’ each have a major stress, and three minor or missing ones, but when the two nouns are put together into ‘elevator-operator’ the second element seems to lose its initial strong stress, perhaps because ‘elevator-operator’ is now one noun and is entitled to only one major stress. What had been the major stress on ‘operator’ is now reduced to something less than a major stress but more than no stress at all. The same situation applies to an adjective/noun combination; when ‘the bird is black’ is pronounced, both ‘bird’ and ‘black’, as information words, are entitled to major stresses. However, in the phrase ‘the black bird’ the stress on ‘black’ seems to be less than in ‘the bird is black’, though it still seems to be ‘major’, i.e. stronger than the stress on ‘the’.6

So, to judge by ear (or, perhaps, by expectation plus ear), there seem to be major stresses, and minor stresses, and some sort of intermediate stresses. Although the traditional metrical treatment of stress in English only distinguishes strong from weak, just how many degrees of stress there are, and how they are assigned, is still very much of a problem. Early investigators like Sweet suggest that there are three stress levels; later linguists such as Trager and Smith postulate four. Chomsky and Halle, while denying that degrees of stress are always physically present in utterances, nevertheless suggest up to five degrees of stress, assignable ultimately on the basis of the syntax of the utterance. Philip Lieberman reports experiments which seem to show that although some degrees of stress were discernible by different hearers, the number of degrees varied from two to five, with very little agreement about the assignment of grades of stress between the extremes; that is, degrees of stress between the highest and lowest were randomly distributed by those tested.7 Again, these results may be affected by the notorious ‘looseness’ of normal enunciation in casual discourse (the phenomenon that produces elision discussed above), which may not be so loose in the performance of poetry, or of discourse in the ‘formal style’.

The ‘minimal’ stress system that discerns only two levels of stress, strong and weak, seems inadequate to describe the Ajax lines.8 Here, some of the spondees can be explained by the excessive number of short information words. ‘Vast Weight’ and ‘move slow’, two of the possible four spondees in two lines, are spondees because of the immediate juxtaposition of two monosyllabic words of that kind. The other spondee, ‘too, la[bours]’, and the possible fourth spondee, ‘some Rock's’, cannot be so explained, however; ‘too’ and ‘some’ are not information words. On the other hand, ‘too’ is a ‘transition marker’ or sequence marker, a sort of marshal of the discourse, keeping the sentences in order, and transition markers like ‘too’, ‘first’, ‘then’, and so on, also bear a major stress. That is one reason why ‘too, la[bours]’ is a spondee.

The case of ‘some Rock's’ is more difficult. ‘Some’ is not an information word; syntactically it seems to be either a determiner like ‘the’ or ‘a’, or a numeral, like ‘three’, but, unlike ‘three’, indefinite in number. ‘The’ or ‘a’ never bear major stresses (except in contrastive situations, as in ‘You're not the John Jones’); numerals, as a special (rather odd) class of adjectives bear an intermediate degree of stress. However, ‘some’ in ‘some Rock's’ is not an indefinite numeral, since we know how many rocks Ajax will be throwing (one); what we do not know is which rock he will throw. Consequently, it is doubtful whether ‘some Rock's’ is a spondee, or merely a heavy type of iamb. (‘Some’ as in ‘some Rock's’ has been called an ‘indefinite demonstrative’, and demonstratives do not bear major stress, unless they emphasize a contrast ‘these men, not those’.)

It seems to be necessary for the description of the rhythm of poetry (its actual intonation, as distinguished from its metre) to be able to assign intermediate degrees of stress. Otherwise every iambic pentameter line would be analysed like every other, with insertions of spondees and pyrrhic feet perhaps for the doubtful cases. What metrists have been describing as ‘hovering feet’ or, as Vladimir Nabokov calls it, ‘scud’,9 are those in which the syllables contrast weakly with each other, sometimes because they display some variety of intermediate stress. In the Ajax lines, the spondees and the pyrrhic feet all seem to be of different weights.

(a) ‘some Rock's’ is a doubtful spondee. If a major stress were numbered I and no-stress numbered 4, the pattern for this foot would, it seems to me, be something like ‘s me R

me R ck's’, for a very low degree of contrast, but with some contrast in a weaker/stronger pattern – in other words, a type of iamb.

ck's’, for a very low degree of contrast, but with some contrast in a weaker/stronger pattern – in other words, a type of iamb.

(b) ‘vast Weight’ is much heavier, but even here, to my subjective ear, it is not really a spondee. I would again as a (‘v st We

st We ght’), assign a 2–1 pattern to it type of iamb, if an odd one.

ght’), assign a 2–1 pattern to it type of iamb, if an odd one.

(e) ‘too, la[bours]’ is close to a ‘true’ spondee, ‘t o, l

o, l ’, complicated, however, by the pitch pattern (to be described below).

’, complicated, however, by the pitch pattern (to be described below).

(d) ‘-bours, and’ – this foot (the pyrrhic foot) is, subjectively again, quite weak in stress; but, while assigning no more than a 4–4 pattern to it (the weakest possible), the actual material pronounced in ‘-bours’ requires more effort than ‘and’. It is doubtful, however, if we should mix systems this way in the determination of the inherent rhythm of a line. Perhaps a measure of syllable weight could provide a parallel measure to the line's inherent stress rhythm.

(e) ‘move slow’: for reasons to be treated below, this foot is a very heavy spondee indeed: perhaps ‘m ve s

ve s ow’ like la-’, ‘t

ow’ like la-’, ‘t o, l

o, l -’, and for essentially the same reason. The rise in pitch on ‘slow’ may suggest that ‘slow’ has a heavier stress than ‘move’, but this may be an illusion. Indeed, the relationship between stress and pitch is highly complex and has not yet been satisfactorily described.

-’, and for essentially the same reason. The rise in pitch on ‘slow’ may suggest that ‘slow’ has a heavier stress than ‘move’, but this may be an illusion. Indeed, the relationship between stress and pitch is highly complex and has not yet been satisfactorily described.

Therefore, of the four spondees in the Ajax lines, two are and (‘t o, l

o, l ’, and ‘mo

’, and ‘mo e sl

e sl w’), one is weaker and more iambic (‘va

w’), one is weaker and more iambic (‘va t We

t We ght’), one is weaker and (‘so

ght’), one is weaker and (‘so e R

e R ck's’) and may not be spondaic at all. What all hese feet have in common is a contiguity of stress and weight – in none of them is the first syllable more than one degree weaker than the second. A ‘true’ iamb, it would seem, must be truly contrastive; it must display patterns like 3–1, 4–1, or 4–2. Anything closer begins to break the iambic metre, a fragile flower at best.

ck's’) and may not be spondaic at all. What all hese feet have in common is a contiguity of stress and weight – in none of them is the first syllable more than one degree weaker than the second. A ‘true’ iamb, it would seem, must be truly contrastive; it must display patterns like 3–1, 4–1, or 4–2. Anything closer begins to break the iambic metre, a fragile flower at best.

But the obstructive effect in the Ajax lines derives as much if not more from pitch and junctural phenomena as from transition difficulties or stress heaviness.

Stress, pitch and juncture as stylistic phenomena in English can be omitted without losing the meaning of an utterance, if, in casual discourse, the speaker performs in a gabbling monotone. For most utterances which are unambiguous syntactically, pitch and juncture are not strictly necessary for communication: the facta, or what, that is involved, may be adequately communicated with out them. For example, internal juncture (which can here be described as a kind of internal pause) can be omitted, or be minimally present, or maximally present, without much effect on the meaning of the line ‘John loves Mary’.

(a) None: John-loves-Mary

(b) Minimal: John | loves-Mary

(c) Maximal: John | loves | Mary

In (a) there is no internal pause; in (b) there is one; and in (c) there are two. All three performances are equally acceptable in terms of the communication of information.

However, this is not to say that omission of juncture is entirely without penalty, and here we clearly enter the sphere of stilus, of how, in respect of the information that is communicated (see pp. 22–4 above). In this sphere, external juncture (between sentences) seems to be less expendable than internal juncture; when someone says, all in one breath,

John-loves-Mary-I-hate-them-both

there is an impression of haste and incomplete control of emotion. This is not necessarily so if the speaker produces an external juncture but no internal ones for the utterance:

John-loves-Mary | I-hate-them-both

In addition, if there is internal juncture, it must also follow certain rules of precedence, or a spasmodic, hesitant effect is produced. In

John-loves | Mary

it sounds as if the speaker wished to produce a dramatic effect by delaying the name of Mary, or could not bring himself to say it. Of course, if there is an internal juncture (even a correct one) and no external one, the effect is even odder:

John | loves-Mary-I-hate-them-both

While there is nothing to prevent speakers from gabbling, or jerking out their sentences spasmodically, the very fact that their performance can be described by such pejoratives as ‘gabbling’ or ‘spasmodic’ suggests that there are regular traditional or canonical styles of performing sentences and discourse, or of expecting them to be performed.

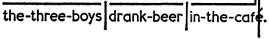

With this system in mind for most normal utterances, let us examine ‘abnormal’ ones. Inversion of normal sentence order produces what we might call ‘emergency phonology’. In such situations, internal junctures and odd pitch patterns multiply. For example, the pitch-juncture pattern of a normal sentence – ‘the three boys drank beer in the café’ – could be

Inverted – ‘the three boys drank, in the café, beer’ – will probably sound like:.

The internal junctures are much more necessary in the inverted situation, and there are more of them. In addition, unusual syntactic structures are signalled by the odd pitch-curlicues and pauses indicating a noticeable oddity in style.

Pope employs this scheme in his poetic game. In the first Ajax line, the inversion of ‘some Rock's vast Weight’ introduces intonation complexities, enjoining the use of three internal junctures instead of two.

Normal order: When Ajax | strives | to throw some Rock's vast Weight

Inverted: When Ajax |strives |some Rock's vast Weight | to throw

There is another reason, a very interesting one, for the obstruction in this line. ‘Some Rock's vast Weight’ is not a literal expression; since he throws an attribute of the rock, not the rock itself, it is a ‘metonymy of adjunct’. I feel that there is a convention (a ‘paralinguistic’10 convention) covering the style of such non-literal stretches pf utterance as those containing distinctive rhetorical figures of this sort: the speaker slows down the tempo of the utterance (or imagines it slowing) to signal the secondary interpretive nature of the rhetoric. To test this notion, imagine that ‘some Rock’ were changed to ‘Sum Rok’, and it were regarded as the name of a Korean wrestler. Then the phrase ‘Sum Rok's vast weight’ would have a literal though bizarre meaning; Ajax would be described as attempting to throw an enormous piece of equipment owned by a Korean wrestler, and there would be no slowing of tempo:

When Ajax strives some Rock's vast Weight to throw

[ slowing of tempo ]

When Ajax strives Sum Rok's vast weight to throw

[no slowing of tempo]

Therefore, by a combination of transition difficulties, a certain excess of information words with a concomitant increase in major stresses, emergency phonology (for the inversion) and paralinguistic slowing of tempo (for the rhetorical figure), Pope achieves a very obstructed and difficult style of performance in the first Ajax line.

This obstruction is relevant to the content of the line and reinforces it; the sound (actual or potential) seems ‘an echo to the sense’. However, if the sense were entirely different, or opposite, but the phonological and paralinguistic reasons for obstruction remained, an obstructive performance would still be inevitable, but it would not now seem to reflect the content. As in Robert Browning, for example, it might seem to be characteristic of the personal style of the poet, and not part of the public literature game: ‘When Ajax strives some toy's light weight to toss’ is as difficult to perform as the original, but the obstruction now has a different function, and perhaps indicates a hesitant or awkward style in the speaker.

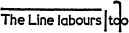

In the second Ajax line, the obstruction is not due to transition problems at all, nor are there any noticeable rhetorical figures to slow the tempo. In

The Line too labours, and the Words move slow

there is no difficulty in moving from syllable to syllable. However, there is an inversion, with concomitant ‘emergency phonology’, though of rather a different sort than in the first line.

The performance of

is much easier than

There is, however, a much more subtle source for the obstruction than syntactic inversion in this half-line. The use of ‘too’ is mildly unorthodox, as we will see, and the nature of this difficulty causes a difficulty in the speaker's forming a hypothesis about the syntactic structure of the line, and therefore a difficulty in being able to ‘perform’ the line.

Any line which is syntactically ambiguous will be difficult to perform. ‘We move on Tuesday’ could be performed as

(a) We-move | on-Tuesday

(b) We-move-on | Tuesday

with concomitant differences in meaning based on different syntactic structures. The speaker, confronted by the (written) sentence ‘We move on Tuesday’, might hesitate before he launches out on a performance, or perhaps perform it in a mechanically divided manner:

We | move | on | Tuesday.

This bears out Chomsky's contention that ungrammatical ‘strings’, sequences of words to which it is difficult or impossible to assign a syntax, tend to be performed as strings of unrelated words.11

This condition applies to the first half-line of the second Ajax line. ‘The Line too labours’ is semi-grammatical because of an unorthodox use of ‘too’, and this semi-grammaticality brings about a potential hesitation in performance. The sentence does not fall apart into a string of unrelated words – it is not ungrammatical – but it is not immediately perceivable as transparently grammatical and performable as such.

The orthodox rule governing the use of ‘too’ (not the intensifier ‘too’ of course, as in ‘too hot’) is clear and unequivocal:

Too is to be used only as an indicator

of repetition, and only in a sentence differing

from the too-sentence in one particular.

The orthodox operation of too can be seen in

John likes music.

John likes art, too.*

It would sound very odd to go violently against the rule:

?? John likes music.

?? Mary likes beer, too.

This rule is so rigid that when it is infringed even slightly there is a hesitation in accepting the result:

John likes Botticelli.

? Mary likes art, too.

The single question mark suggests that while the rule is ultimately seen to be followed, there is a lack of ‘transparency’, and a consequent hesitation in processing the result. In short, there is semi-grammaticality.

This is the situation in the Ajax lines.

When Ajax strives …

The Line too labours.

‘Strives’ and ‘labours’ are closely synonymous, but they are not the same word, and the hesitation concomitant with this situation causes a hesitation in performing the line, and thus determines its ‘hesitant’ style. The hesitation would not exist if ‘labours’ were replaced by ‘strives’, as the reader can experience by pronouncing them:

When Ajax strives …

The Line too strives …

The internal junctures in

The Line | too | labours

are thereby lengthened by the hesitation. It seems to me that the pitch pattern also is altered, becoming higher than normal over ‘too’, possibly as a result of the performance of a semi-grammatical utterance.

Semi-grammaticality of an even subtler cast accounts for the obstruction in the second half-line, ‘and the Words move slow’. The line would move more quickly, that is, with fewer internal junctures, if it were one syllable longer! If ‘slow’ were ‘slowly’ the performance would not include an internal pause that is otherwise potentially there:

The-Words | move | slow

The-Words | move-slowly

The presence of the adjective form ‘slow’ for the more regular adverb form ‘slowly’ produces a semi-grammaticality. The adjective-form is not ungrammatical; there is ample precedent for such a construction in such phrases as:

The candle burned blue.

Charles jumped clear [of the ship].

The moon shines bright.

However, this ‘quasi-predicative’ form, as it has been termed,12 is not as regular in English as the common verb manner-adverb construction (‘the candle burned brightly’), and this semi-grammaticality also causes hesitation.*

The second Ajax line, therefore, owes its sense of obstruction entirely to the performer's hesitation in deciding what the syntax is of each half-line, and whether the half-line in question is truly grammatical. Except for the emergency phonology attendant upon the inversion of ‘too’, the style of the line is entirely a matter of high-level mental processing, and has nothing to do with the sort of low-level phonological-articulatory processing that accounts for the obstruction of the first Ajax line.

In playing the public literature game, Pope has so deftly built a wide range of stylistic obstructions into the Ajax lines that he has managed to manipulate the reading habits of his audience long after his own death. The public literature game has rarely been played so brilliantly – or so openly.

This sort of analysis has two results. First, it enables the critic to be completely precise about the source of stylistic effects. Second, and consequently, the craft of a master poet becomes accessible, not only to critics, but to other poets. If a poet wished to write an obstructed line, or to remove obstruction from a line, this sort of analysis could help him. For example, it should be possible by such a technique to write a line that was so obstructed that it would be very difficult indeed to perform. I suggest that the following line (which I have just composed) provides an example of egregious obstruction:

Ring-grim, my great Tom-cat, nears slow

winter's swamp

If the reader will give this line a careful performance, it should read very slowly and with difficulty. The doubt about whether ‘slow’ modifies ‘winter’ or not seems to me to reinforce the hesitation past the point of semi-grammaticality, and the transitional difficulties are almost insuperable.

As we have seen above, the intonation of a line of poetry is, like the intonation of every other sort of utterance, considerably determined by its syntax. However, the syntax of a line of poetry, or a complete poem, may be shaped by the poet for other purposes than those of intonation.

In a poem by Robert Lowell13 (which is about, among other things, pollution of the environment) there is a powerful line:

There sewage sickens the rebellious seas.

Much of the vigour of the line derives from what seems to be a fight over precedence between the verb and the adjective: just how permanent is the ‘rebellion’, and what is the temporal relationship between the rebelling and the sickening? The reader is required to mediate among the following possible meanings:

(a) Sewage sickens the seas, which once had been rebellious but because of pollution are now too ‘sickened’ to resist further pollution.

(b) Sewage sickens the seas which once had been rebellious against pollution, but although still rebellious are rapidly losing the will to rebel.

(c) Sewage sickens the seas, which, however sickened, are still, and will continue to be, rebellious when faced with a threat of pollution.

(d) The seas have been and always will be rebellious, whether or not they are threatened with pollution, but their natural and external rebellion is presently contending with a sickening power – pollution.

(e) Sewage sickens the seas, which become rebellious upon sensing the encroachment of pollution.

Syntactic structures account for the various interpretations as well as the total effect of conflict caused by the fight of interpretations. The effects turns upon the position of ‘rebellious’. There are two possible positions for noun-modifiers in English:

(a) after the noun, as complete relative clauses (‘the hat which was black’) or reduced (‘the man dancing on the table’);

(b) before the noun, as simple or complex noun-modifiers (‘the black hat’)

Noun-modifiers before the noun suggest permanent qualities of the noun they modify: compare ‘the man dancing’ with ‘the dancing man’.14 The seas are permanently rebellious, since the modifier is before the noun; how can they be sickened? Yet permanent rebellion is difficult to imagine; usually it follows upon provocation. Hence the reader's hesitation and conflict, and his search for ways out of the contradiction – all useful for the poet's purpose. We have here what would otherwise be thought of as an inefficiency of expression – an ambiguity – used for dramatic purposes.

This oddity of noun-modification resembles the so-called ‘proleptic’ modifier, as in: ‘In the midst of a peaceful scene, the sultan suddenly shouted at his terrified wives.’ ‘Terrified’ is ‘proleptic’, or anticipatory since the wives are terrified only as a result of the shouting. A non-proleptic version of the line would be: ‘In the midst of a peaceful scene, the sultan suddenly shouted, and terrified his wives.’ The proleptic modifier is a well-known device of Greek and Latin rhetoric, and its effect depends entirely upon the usual interpretation of noun-modifiers, which express a condition existing simultaneously with that expressed by the verb, or at least not affected by it. If the modifier is proleptic this simultaneity cannot exist for semantic reasons, and a heterodox sequential interpretation is enforced upon the line.

Only one of the five interpretations of the Lowell line is truly proleptic – that given in (e). The others also involve an unorthodox sequence but are not entirely anticipatory. Some could, in fact, be called ‘anaproleptic’ (but not ‘epileptic’!), in that the rebelliousness may not be entirely or at all the result of the sickening.

Notice also that the problem could almost vanish if the sentence were in the passive:

The rebellious seas are sickened by sewage.

In the passive form the rebellion precedes the sickening in the sentence form, and therefore makes much less likely any interpretations (like (c) or (d)) which suggest a possibility of continued resistance. Lowell, however, provides an active sentence, with the order of the sickening and the rebellion in doubt, a sentence whose style thus mimes the intensity of the conflict.

Lowell's creative use of conflict between an active verb (‘sicken’) and a permanent (or semi-permanent) quality expressed by the noun-modifier (‘rebellious’) was anticipated by Blake. In Vala, Blake writes of

… cities, turrets & towers & domes

Whose smoke destroy'd the pleasant gardens, & whose running kennels

Chok'd the bright rivers.

Here the permanence of ‘pleasant’ and ‘bright’ are cast in doubt, since it is just these qualities which are ‘destroy'd’ and ‘chok'd’; the subsequent conflict of interpretation closely resembles that of the Lowell lines. In Blake's poem, the adjectives are, in fact, ‘anaproleptic’, in that they represent conditions which have already been altered by the verb.

It could be said that Blake (and Lowell) have simply made syntactical errors which seem here to contribute little if anything to the poetry of the lines, if it were not for Blake's astonishing affirmation of his ‘error’ in Jerusalem. In the first stanza, England's mountains are ‘green’ and her pastures ‘pleasant’. These are ‘true’ adjectives representing permanent qualities, the reader assumes (even though they are placed after the noun in an archaic fashion). Yet as the poem progresses the dark Satanic mills press around the speaker; what now of the ‘permanent’ green and pleasantness of England? Nevertheless, in the last stanza, Blake's syntax deliberately repeats his attribution of ‘green and pleasant’, as if to reiterate a basic conviction that, however the surface may appear, these remain the permanent, visionary and unalterable qualities of England's land.

A good deal of research into many aspects of the relationship between style and syntax has been undertaken in recent years. The present writer has examined syntactic patterning in Hopkins and Blake; M. A. K. Halliday and the present writer have examined Yeats's use of syntax to establish a mood of timelessness; Marjorie Perloff has performed suggestive syntactic analyses on the poetry of Robert Lowell, demonstrating syntactic rhythms miming cognitive patterns; Donald Freeman has been working on the use of syntax by Keats, Blake, and Dylan Thomas; Seymour Chatman, in addition to other projects, has shown how Milton's use of passive noun-modifiers (‘the created world’) in Paradise Lost suggests the presence of the Creator in the world without actually mentioning Him; Irene Fairley has worked extensively on e e cummings; and S. J. Keyser has analysed Wallace Stevens's use of syntactic parallelism and tenses, and the methods by which Stevens forces the reader to re-evaluate the syntax of the poem as he goes along, thus miming its essential thematic elements. These are by no means all of the critics working in this rich new field. The American critic Stanley Fish has been providing a critical underpinning for the analysis of a reader's (putative) reaction to language elements as formal structures in literature, for an ‘affective stylistics’. Roman Jakob-son, as the originator of this school, has constantly provided both theory and precept.15

Modern poets experiment ceaselessly with syntax, for their special effects. Yeats abruptly begins the poem The Cold Heaven, from his early-middle period, with the line:

Suddenly I saw the cold and rook-delighting heaven

‘Suddenly’ is a sequence marker whose use is normally justified only as an evidence of an abrupt transition from a first state to a second. Yeats provides no first state, so the reader is thrust abruptly into the discourse, far too abruptly, as we shall see, for the syntactically complex material he is being asked to absorb. Once into the discourse, the reader is ‘suddenly’ required to interpret an unorthodox syntax in the object of the sentence. The modifiers of ‘heaven’ are not restrictive; that is, Yeats is not making a distinction between a cold and rook-delighting heaven and some other kind. A non-restrictive modifier always carries an emotive charge, perhaps because it is ‘by-the-way’; it always bears gratuitous information, information not seen to be necessary to describe a situation, and thereby valued only for itself.

Restrictive |

Non-restrictive |

I saw two girls. |

I saw a girl. |

The blonde girl winked. |

The blonde girl winked. |

(= the girl who was blonde winked) |

(= the girl, who, by the way, was blonde, winked) |

In the ‘restrictive’ situation, the memory of blondness occurs during the cognitive action underlying and producing the first sentence, perhaps as part of the recognition of the two girls, or just afterwards. It emerges as the restrictive modifier ‘blonde’ in the second sentence, as an essential distinguisher of the two. There is no emotion attached to it and its function as a distinguisher is entirely utilitarian (although perhaps the ‘blondness’ does have more value for the observer than would any other possible distinguisher). In the ‘non-restrictive’ situation, however, it is almost as if the memory of the blondness occurred as the second sentence was beginning to be created or uttered. The value of the blondness was suddenly so extreme that the speaker could not wait to create a separate sentence – ‘By the way, the girl was blond’ – since it was too urgent to put o ff. A cognitive diagram for the creation of the sentences might look like this:

Restrictive |

|

Actual speech: I saw two girls. |

The blonde girl winked. |

Cognitive: (notices two girls: one blonde) (notices winking) |

|

Non-restrictive |

|

Actual speech: I saw a girl. |

The blonde girl winked. |

Cognitive: (notices a girl) (notices winking) (notices blondness) |

|

Observe that there seems to be a contrapuntal structure in the non-restrictive situation, with the ‘winking’ creating a sentence, only to have the ‘blondness’ forcing itself into it when it is only half-created. If the blondness were less startling or valuable to the observer (if it were to wait its turn), the patterns would probably be:

Actual speech: |

I saw a girl. |

The girl winked. |

|

By the way, the girl was blonde. |

|

Cognitive: |

(notices a girl) |

(notices winking) |

|

(notices blondness) |

|

This sequence of three sentences would mirror a casual and consecutive rhythm of cognition, with observations strung out like beads on a thread, with nothing so valuable that you cannot wait to describe it.

In the line, ‘Suddenly I saw the cold and rook-delighting heaven’, the double modifiers of ‘heaven’ – ‘cold’ and ‘rook-delighting’ – seem so intensely important that even when the mind of the speaker, ‘suddenly’ thrust into speech, is beginning to express his vision of heaven, both the coldness of heaven and its capacity to delight rooks, forces itself upon him and into his half-formed locution. A single non-restrictive modifier, as in the blonde-girl example above, shows the mind operating contrapuntally, at a greater tempo than usual. If, as in The Cold Heaven, there are two non-restrictive modifiers intruding at a time when the mind is working at full stretch anyway (‘suddenly’), the mind of the speaker must be at a supernatural pitch, racing like the wind of heaven itself. Indeed, Yeats has many poems in which he represents his mind, proceeding in its quotidian rhythm, being suddenly assaulted by eternity; The Cold Heaven is one of the earliest and best.

This sort of analysis, the description of the varying rhythms and overlays of cognition which produce various syntactic patternings, provides a clear and vivid method of showing the operation of the mind in the double contrapuntal act of observing and expressing. With the revelation of the value system of the speaker – what he values too highly to postpone expressing – this aspect of the public literature game comes close to the other concern of stylistic analysis, the revelation of private individual personality. It is with this subtle and complex technique that we come to the borders of the public game and begin to cross over into the private one.

* It is still an open question, however, as to whether the articulations necessary to perform a line of verse are actually operative in silent reading. No reading is entirely silent, of course; the tongue muscle flexes during silent reading as if preparing for speech. In addition, the ‘motor theory of perception’ suggests that a reader or listener mimes mentally the articulatory action, actual or potential, of the speaker to whom he is listening, or of the writer of the line he is reading. For a treatment of the topic of the ‘buccal dance’, see Delbouille, P., Poésie et Sonorités (Paris: Société d'Edition ‘Les Belles Lettres’, 1961), pp. 57–69.

* Note that Pope orchestrates the last six lines of The Dunciad, Bk. IV, in exactly the same way. The reader can work out the vowel pattern for himself, and will find that almost all of the stressed vowels, and many of the unstressed ones, in these powerful lines are mid vowels or very low, and very grave. Except, appropriately enough, for ‘glimpse’, there are no high-front vowels at all.

* See also Iliad VII, lines 268–9; in the translation of these lines made (or overseen) by Pope, there is a rather feeble attempt at the effect of lifting and heaving a boulder:

He poiz'd, and swung it round: then lost on high,

It flew with Force, and labour'd up the sky.

Pope's precepts, in An Essay on Criticism, are better than his practice.

* Note, however, that in other contexts, ‘proforms’ like ‘do’ and ‘so’ may be present without altering the operation of the rule:

John likes music.

Mary does, too (= Mary likes music, too).

* Perhaps some other word than ‘semi-grammaticality’ should be used here, since one form is as ‘grammatical’ as the other. The difference seems to be one of statistically preponderant choice – if this can be established, perhaps ‘crypto-grammatical’ would be better. The resultant hesitation in performance, however, is the same.