Take these words which are not sealed, and deliver them to another, that he may shew them unto the learned, saying: Read this, I pray thee. And the learned shall say, Bring hither the book, and I will read them: and now, because of the glory of the world, and to get gain, will they say this, and not for the glory of God. And the man shall say, I cannot bring the book, for it is sealed. Then shall the learned say, I cannot read it.

FIGURE 8 Lewis A. Ramsey, Joseph Smith Receives the Plates

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966).

IN 1830 an upstate New Yorker published his own English translation of a lost history of the forefathers of the American Indians, written on golden tablets, that he called the Book of Mormon. Five thousand leather-bound copies were circulated by friends and family, but sales in New York proved disappointing, indeed something of a shock. The Book of Mormon has been dismissed by most nineteenth-century social and cultural historians as simply a poorly written, eccentric religious text of little or no importance to anyone but Mormons. How it came to be (purportedly through an angelic dictation, like the Qur’an), however, is precisely why historians ought to take the book very seriously—as an unvarnished account of America in the 1830s rather than a work of sober reflection, learning, and sophistication, so utterly sincere and uncontrived that an offer to punctuate the text by the publisher was almost more than author Joseph Smith Jr. could bear.

Smith was not a writer: he dictated nearly everything with his name on it save a couple of letters to his wife Emma and the odd journal entry.1 He was not a writer in the literary sense, either, lacking the discipline and indeed the stomach to “murder his darlings,” as Bernard DeVoto once put it.2 Fawn Brodie, however—perhaps Mormonism’s most gifted writer—thought Smith no mean dramatic talent (emotional not intellectual), lacking only “the tempering influence that a more critical audience would have exercised upon it.”3 But this may not quite get at the central problem of any study of the life and work of the founder of Mormonism: how a first book that he dashed off in a matter of weeks became the basis for a new religious tradition—the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with its headquarters in Salt Lake City, Utah, and the smaller but no less significant Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now the Community of Christ), the followers of Joseph Smith III and Emma Smith who chose to remain in the east, eventually reclaiming the original site of the early Mormon New Jerusalem (Independence, Missouri) near Kansas City as their capital and ecclesiastic command center.

The Book of Mormon has not improved with age and some minor editing—at least not in the minds of most critics. As books go, it is still viewed as something of the ugly duckling of American religious prose. As religions go, however, Mormonism has gone on to become the goose who laid the golden egg, attracting a congregation of upwardly mobile, well-educated, middle-class men and women who are almost too American—conservative in lifestyle, Republican in politics, and evangelical in religion. To what degree such an impressive institution can be credited to a book not only of questionable literary value but constantly under attack for a multitude of gross historical inaccuracies and anthropological and archaeological anachronisms and, perhaps most vexing of all, persistently suspected of having been plagiarized in part or in whole is the question. And largely because it appears to insult the intelligence of literate and thinking people, purporting to be a revelation from on high, the great and overarching dream of most would-be deconstructions is to explain it using either as few or as many contemporary sources as their argument demands. And yet, after almost two hundred years, we may be no closer to unraveling the mystery of the so-called translation of the golden plates that Smith claimed to discover in a hill behind his home in Palmyra, New York, and published under his own name as the Book of Mormon in 1830. Unsure how he did it, we are even less sure why.

The question of how he did it has tended to monopolize the discussion. Of course, Smith was not exactly silent on the matter, informing an incredulous press that he translated the golden plates by “the gift and power of God,” explaining that something he called “the Urim and Thummim” (taking his cue from the Old Testament, though yanked out of context) that had been included with the plates had made translating as simple as falling off a log. Few dispute Smith’s native intelligence or sense of his Yankee environs. The Book of Mormon, most critics agree, can be seen as a rather brilliant summary of all the major issues of his day. Of vast historical importance, the Mormon prophet can be seen as antebellum New York’s most famous and comprehensive chronicler of popular culture—preferring the company of people over a good book, heated debate rather than quiet reflection his modus operandi.4

The idea of Smith as an aural-oral learner has possibilities and dire implications for understanding the man and his work, though I use it here merely as a heuristic device in an all-too-brief analysis of the important question of how before moving on to address in detail the whys and wherefores. My hope is to propose a much simpler, less sinister, and ultimately more plausible explanation than that trumpeted by critics and a growing number of self-appointed psychotherapists.5 Recent neo-Freudian attempts to suggest that a bone operation on his leg as a child (which left him crippled) is the alpha and omega of Smith are perhaps the worst offenders.6 Reductionist studies—past and present—seem too focused on the supposition that Smith had a parallel antebellum work open in front of him that he used extensively to create his own text, the main problem being that they have yet to put their hands on a copy of the posited manuscript that they can attribute to some poor New England cleric who was cheated out of his royalties by the “Mormon imposture.”7 The truth is that local libraries are likely only ever to offer clues to the mind of the Mormon prophet. But since the written record is all they have, scholars can only do their best, acknowledging that in the case of this aural-oral man his sum must remain quite a bit greater and more unwieldy than his parts. Smith was neither a writer nor a reader and why that was may go a long way toward answering the question of how and why he did all the things he did.

The way he tells his story offers hints as to some of his epistemological strengths and weaknesses and how his mission could not avoid taking them into account, making the necessary, sometimes unconscious adjustments. That he claimed to translate using an instrument of Newtonian magnitude, rather than purely by divine inspiration, may be significant, for example. According to the orthodox understanding, the Urim and Thummim were two thick lenses that Smith used to read the original texts, simultaneously dictating the English translation to a scribe who sat on the opposite side of a drawn curtain.8 “These spectacles,” one contemporary source explains, “were so large, that, if a person attempted to look through them, his two eyes would have to be turned towards one of the glasses merely, the spectacles in question being altogether too large for the breadth of the human face. Whoever examined the plates through the spectacles, was enabled not only to read them, but fully to understand their meaning.”9 The Book of Mormon includes a discussion of the original language and script (Reformed Egyptian?), which, it suggests, allowed more to be crammed on one page than Hebrew would have permitted. Without the Urim and Thummim, or “interpreters,” as they are also known,10 one presumes that reading the text would stymie any ordinary reader. According to the scholarly account, Smith used a peep stone from his treasure-hunting days to read the original, burying his head in a hat to shut out any light and dictating extemporaneously for hours at a stretch.11 Although these accounts differ, both suggest that Smith’s natural vision was problematic and that he may not have been a reader because of a visual dysfunction.

Those who seem confident that Smith must have translated with something in front of him, perhaps making modifications as he went along, do not give his prodigious memory the credit it may deserve. Again, the scholarly account suggests that the first 116 manuscript pages were lost, the golden plates and spectacles were returned to the angel and, along with the 116 pages, never seen again. The Book of Mormon as we have it was thus written completely from memory, or by inspiration.

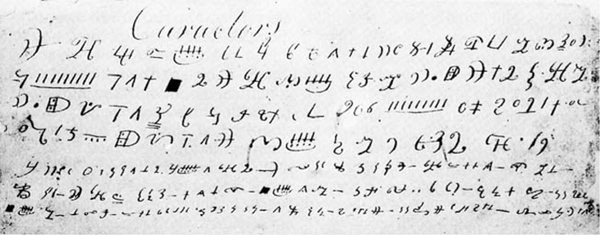

Martin Harris, scribe and financier of the first edition of the Book of Mormon, pestered Smith for proof of the veracity of the golden plates that he might show an expert of ancient languages. After much consternation, Smith consented to furnish him with a handwritten copy of the characters and other minutiae inscribed on the golden plates. The venerable Columbia College professor of Greek and Latin Charles Anthon agreed to meet with Harris and render an opinion. Harris insists that Anthon made a brief inspection and concluded that the hieroglyphs were true “Egyptian, Chaldaic, Assyriac and Arabic” characters, wrote a letter to that effect, and then, after hearing that the plates had been a heavenly delivery, quickly tore it up. Anthon’s subsequent offer to translate seems to have been less than sincere; one can imagine him smirking when he invited Harris to bring the plates the next time he came to call. When Harris naively explained that a portion of the plates was sealed, Anthon simply replied, “I cannot read a sealed book.”12 In other words: Get out!

A year or so after examining the parchment, Anthon described the pages as a truly awful transcription of Greek and Hebrew letters with a Mexican calendar thrown in for good measure.13 Had Anthon’s specialty been early childhood education rather than classics, he might have known better how to interpret it? His description is very revealing all the same: it was a “singular scrawl” consisting of “all kinds of crooked characters disposed in columns” (p. 14). So much crooked lettering and a penchant for vertical columns would have alerted any grade-school teacher that here was proof not of a plan to deceive the learned but of a severe reading and writing disorder? The degree of scrawl is consistent not only with dyslexic transcription but with that done without the aid of a book—from memory, in short (one side effect of dyslexia is an inability to read and write across a page; the tendency is to curve the writing downward and to write in columns—especially when doing so without the aid of a text to copy).14 (Interestingly, many samples of Smith’s mature handwriting are perfectly legible, maintaining a steady flow of lettering across but down.)15

FIGURE 9a. A Facsimile of the Book of Mormon Characters

William E. Barrett, The Restored Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1949), p. 33

9b and c. The Mark Hoffman Forgery of the Anthon Transcript

Dean C. Jessee, The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1984), pp. 225–226.

Lost in the shuffle and not likely ever to be recovered, should the Anthon transcript magically reappear,16 it would no doubt add further weight to the theory that Smith’s transcription story was a fabrication, something critics have concluded beyond any doubt of the Book of Abraham (another book of scripture he produced using extant Egyptian funeral texts). But the Book of Abraham merely furnishes clear proof that Smith did not translate in the conventional academic way, which is hardly conclusive evidence of deception since Smith made no claims to operate solely within the accepted norms of modern linguistics. He thumbed his nose at the Anthons, considering their lack of imagination a greater evil than his paucity of learning. And let us not forget that virtually no one in the academic community at that time, and certainly not Anthon, whose expertise was in Greek and Latin, could read Egyptian. For example, when Oliver Cowdery, another of Smith’s scribes, got to try on the mantle of extemporaneous translation, he failed miserably—largely, it seems, because he lacked the precise aural-oral and imaginative skills with which Smith was so richly endowed. In a special revelation after the fact, Smith forgives this failure, attributing it in part to Cowdery’s fear and lack of intuition and retention.17 “For, do you not behold that I have given my servant Joseph sufficient strength, whereby it is made up? And neither of you have I condemned” (sect. 9:12). Cowdery was, among other things, a schoolmaster (he taught some of the Smith children, in fact), and one suspects that with this revelation elevating the oral and imaginative above mere literacy in the divine scheme of things Smith may have been indulging in a little richly deserved payback for some injustice that he felt he had suffered at the hands of an antebellum schoolmarm.

How then did Smith produce his masterwork? Not in so precise or literal a manner as most of his followers wanted to believe and indeed were led to believe, but not altogether differently from what Smith and witnesses claimed, either. In some respects, one cannot help admiring Smith’s courage, his refusal to let a handicap (several perhaps) stop him from his divinely appointed rounds. He went to extreme lengths, to be sure, but given the temper of the times his lack of candor was a necessary and altogether forgivable evil. In fact, the how leads naturally to the why, the ultimate reason for this inquiry.

The idea of the Mormon prophet as an aural-oral man suggests that he was well suited to a classroom of another, altogether male, and, as it turns out, aural-oral kind, where his disabilities were cause for celebration rather than reason for a ruler across the knuckles. When one learns more about Smith’s native New York, one comes to see Smith as a natural leader in a decidedly patriarchal order of men for whom the spoken word and memory were paramount, who read and wrote as a last resort, books being a vehicle of enlightenment for lesser minds. The Masonic traditions of oral transmission from father to son in secret male rites of passage, the communication of cherished patriarchal shibboleths under cover of darkness in whispered tones—mouth to ear—the use of the blindfold and other highly symbolic and allegorical paraphernalia amounted to a perfect environment for someone like Smith, whose eyes were well suited to the dark (however one chooses to understand this). And then, without warning, tragedy struck, which for an aural-oral savant and Masonic hopeful like Smith made his bone operation a walk in the park: the murder of Captain William Morgan, a brother, by one or more of his own. The male world of his native United States and its premier educational, social, political, economic, and religious twin tower—Freemasonry—toppled to the ground, leaving Smith, a bemused Masonic sophomore, with few options but to build it anew or perish.

FIGURE 10 Sample of Joseph Smith Jr.’s Handwriting (Early Adulthood)

Dean C. Jessee, The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1984), p. 235.

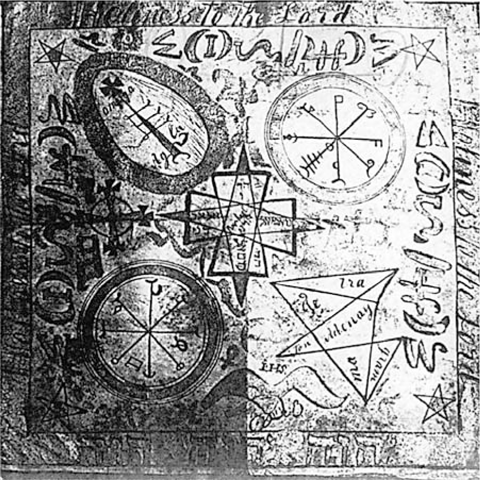

I am not suggesting here that Smith’s eyes were so bad, his reading and writing so rudimentary, that we ought simply to take pity on the lad and the religion he miraculously cobbled together using a prodigious memory based on the spoken word. A manuscript copy of the Book of Mormon with someone else’s name on it has yet to be discovered.18 Until such time, it makes sense to presume that Smith is the book’s author. That he translated anything in the conventional sense seems unlikely, as I have already suggested, but that he plagiarized some written text makes even less sense if we agree that a reader he was not. There might even be a case for the golden plates, perhaps a Masonic mnemonic device that he used when translating. Returning to the Anthon transcript and the two facsimiles, one not fitting Anthon’s description and the other a modern fraud, what Harris gave the Columbia professor of Latin and Greek to examine might have looked something like the artifact reproduced in figure 11. This is not just any antebellum New York family magical “lamen,” or parchment, but the property of the Smith family, described in some sources as a “Holiness to the Lord” parchment with no connection to Masonry. It fits Anthon’s description of the characters he was shown: a singular scrawl with classical lettering going in every direction is precisely how a Classics professor might have seen it. If the Anthon transcript was indeed a transcription from memory by Smith—whose writing was not the best—then it would have been a sight to behold, to be sure. This Smith family treasure (and it is golden) might tell us a great deal about what Smith was cooking up behind a curtain, donning the biblical Urim and Thummim in order to see straight—if only we knew how to read it. What is remarkable about this artifact is how completely it describes what Smith would go on to create. Is this—the bad grammar of notwithstanding—the golden plates?

While there is much about the Smith family parchment that is certainly hard to make out, not all of it—the characters, for example—is impossible to decipher. For this, we, like Smith himself, require the aid of the Urim and Thummim—or, rather, the knowledge that the Urim and Thummim Smith used come out of not the Bible but Masonry. A breastplate with two stone lenses affixed to a golden bow or chain is the Masonic representation of the device (a slight but important departure from the Bible). In Masonic encyclopedias, one can easily find the Urim and Thummim that Smith used, a device reserved for “the High Priest alone, for the purpose of obtaining a revelation of the will of God in matters of great moment.”19 Smith drew a curtain or put his peep stone (which is what he apparently used) in a hat, out of sight—hiding the Urim and Thummim from view as the high priest of biblical and Masonic tradition is wont to do. Although he would not let anyone see the golden plates without the expressed permission of the Deity, they were, in some respects, a red herring; the real issue was whether anyone would be permitted to view the Urim and Thummim. According to the esoteric Masonic understanding, moreover, the Urim and Thummim have some connection to the Egyptian deities Ra and Theme—light and truth—the first of these said to function in a double capacity, increasing both physical and intellectual light (2:1072). One is reminded yet again of Smith’s visual acuity, or lack thereof.

FIGURE 11 “Holiness to the Lord,” Smith Family Artifact

D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (Salt Lake City: Signature, 1987), figure 50.

Understanding that the Smith family parchment can be read through Masonic lenses makes it possible to decode quite a lot of it. In fact, it is all too legible. It can be seen as a Masonic tracing board, a kind of key containing all the important icons and Masonic essentials of the degrees. A border and the points of a compass are standard-issue Masonic iconography. The English at the top and sides, “Holiness to the Lord,” is the motto of the Royal Arch, and the Hebrew characters at the bottom (and perfectly good Hebrew it is) spell the Divine Name, which is the Grand Omnific Word of the Royal Arch and appears at the bottom of actual Royal Arch tracing boards. Just inside the border are three sets of identical lettering (the sort of Greek that Anthon ridiculed). These, too, are perfectly acceptable Masonic insignia, possibly shortened and symbolic representations of the Greek that appears in the Royal Arch tracing boards that made a brief appearance around the end of the eighteenth century. At the EN APXH HN O ΛOΓOΣ: “In the beginning was the Word” (2:885).

It is in this Greek that the Smith family’s tracing board makes a classic mistake: their transcription begins with a capital sigma when it should be a Greek capital epsilon, ending with a backward version of the same letter, instead of a capital sigma per se (proof perhaps that their Greek was not the best). The second character in the string of Greek on the Smith’s tracing board is either an xi (Ξ) or a theta (Θ) if the lettering is read in a column from top to bottom. There are two Xs in Greek, X (chi) and Ξ (xi). The former is the first letter in the word Christ, and that it looks like a cross has always been cause for Christian exegetes to break out the champagne. If the Greek on the sides of the Smith’s tracing board is an abbreviated form of EN APXH HN O ΛOΓOΣ, then the second character could represent APXH, but with a Ξ instead of a X. (When viewed from the side, it looks something like an all-seeing eye, more reminiscent of the symbolism of ancient Egypt than of early Christianity.) But this letter could also be a Θ, or theta, the first letter of the Greek word for God, theos—ΘEOΣ if written in capital letters, θεoς in lowercase. (And if this is the word that is meant, what follows might simply read “the word of God,” a reference not to Christ, it turns out, but to “one who speaks [treats] of the gods and divine things, versed in the sacred science.”20

What looks like a capital s (laid on its front), the next letter in the series might be the Greek letter ς or a lowercase sigma. In Greek there are two sigmas: σ is used when the letter occurs in the middle of a word, whereas ς is used at the end.

Notably, vowels are absent. Hebrew is not vocalized. In that language, the vowels of the Divine Name are a mystery too. One does not read aloud, or even try to speak the ineffable name—and leaving out the vowels or inserting incorrect ones is how rabbis guarded against this. Thus what appear to be a capital letter i in brackets and a capital s on its face are more than likely the first and last consonants of the Greek word for God, Θ(εo)ς, or theos. Thus far the text reads, E(N)21 Θ(εo)ς, or “in God.”

What follows is not as straightforward or easy to read, but one suspects it is a variant of the Greek word ΛOΓOΣ, logos, translated as “word.” But this string of characters, too, is pregnant with other possibilities. The fourth character in the series—leaning slightly to the right—looks for all the world like a capital letter l, not quite the lowercase lambda (λ) but possibly the capital (Λ). The characters that follow appear to be a capital h with the number 2 drawn through it—probably intended to be a capital lambda (Λ), a crescent moon—likely some kind of magical symbol—and then a backward Σ or capital sigma. Here, too, vowels are omitted, in keeping with the Hebrew. The numeral 2–H combination could be shorthand for the two capital etas that appear back to back in EN APXH HN O ΛOΓOΣ. However, the character that looks for all the world like a number 2 could also be a lowercase gamma (γ). The two vertical bars running perpendicular to the tail of the gamma form a double or “patriarchal” cross, the original badge of the Knights Templar and Knights of the Scottish Rite.22

In any event, the Greek atop the Smith family tracing board seems translatable as one of the following: “In God(’s) Word,” or “God in the Word,” or “in God is the Word,” or, finally, “the Word is in God.” If Logos here is Christ, then the passage may read “in God is Christ” or simply “God is Christ”—which, incidentally, is the Book of Mormon’s understanding. In the Scottish Rite, the Word, or Logos, is among the greatest philosophical and cosmological mysteries. That grand patriarch of the Scottish Rite, Albert Pike, for example, devoted a substantial portion of his mammoth Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry to the issue of the “Word in God,” making extensive use of the cabala, or Jewish occult literature.23 If my translation is correct, it may be more than accidental that the text accords with the quintessential lesson of the Master, or Third Degree of the Scottish Rite, that “the Word is in God” (p. 98). If the Smith family tracing board is of some mystical Masonic derivation, this might explain the creative departures based on the Royal Arch or York Rite that possibly derive from something in the cabala.

As to the rest of the parchment, what appear to be a compass, two magic circles to the northeast and southwest, and an unorthodox pentagram at the bottom right-hand corner have an occult connection—which proves helpful in deciphering some of the blotchier Hebrew and English writing. The character resembling a 4 atop it all could be just that, the numeral 4. A stylized number 4 is the sign of Jupiter (Smith’s planet, it so happens, as he was born in December). Francis Barrett’s 1801 work The Magus, or Celestial Intelligencer; Being a Complete System of Occult Philosophy furnishes more than enough assistance in sorting out the meaning behind the more arcane elements of the Smith family tracing board.24 The magic circles seem more or less the sort meant to ward off evil spirits or conjure spirits to some sublime end or purpose. The compasslike set of steep isosceles triangles in the middle bears the name of Raphael, written in English and dead center. The Hebrew letters aleph, daleth, nun, and yod directly underneath spell adoni, that is, Lord. If the first Hebrew letter in the string to the right is a shin, then what follows might be shem’el, that is, “the name of God.” The southerly triangle of the compass reads qoph, daleth, mem, aleph, lamed (qdm’l), from the Hebrew root qdm, and thus “ancient God” or “God is ancient.”25 This may be a variant of “Adam Kadmon,” the name of the “Primal or First Man” in the cabala, which Pike contends “might be called by the name Tetragrammaton.”26 The daleth, nun, and yod on the left are the last three letters in adoni. However, they appear directly underneath aleph, lamed, aleph, pe (a phonetic spelling of aleph, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet?), and perhaps A(leph)doni, as in LORD is intended. The ha and resh to the left and the ha, resh, and waw at the top could be har, as in “hill or mound,” or the title for the patriarchs, or the numbers 4, 5, and 6 (if the resh is instead a daleth).27

Four is also a Masonic number, the tetrad of Pythagoras and a sacred number in the Fifth Degree of the Scottish Rite, that of the Perfect Master. Masonic encyclopedist Robert I. Clegg explains: “In many nations of antiquity the name of God consists of four letters, as the Adad, of the Syrians, the Amum of the Egyptians, the Λεoσ of the Greeks, the Deus of the Romans, and preeminently the Tetragrammaton or four-lettered name of the Jews.”28 This lends credence to my translation of the Greek atop the Smith family tracing board. It may also explain why there are four pentagons, the pentagon being a figure in the Thirty-second Degree of the Scottish Rite (the Camp of the Sublime Princes of the Royal Secret) (2:762). Indeed, the somewhat droopy pentagon at the bottom left is Pythagorean (a mystical work of analytical geometry), bearing no resemblance to the magical pentagons in Barrett. In the middle are the Hebrew word for Lord, adonai, and the word Te-tra-gram-ma-ton (the English for the Divine name) divided into five equal parts. Directly above the head of what appears to be a bird (possibly a dove?) are the initials I. H. S. They, too, are Masonic—extremely and undeniably so: I.H.S. is the sacred monogram of the Knights Templar, short for in hoc signo, “by this sign shalt thou (conquer),” the motto of the American branch of the order.29 The four crosses to the left are Templar or possibly Maltese (1:254) (The little Egyptian Crux Ansata is another conspicuous ritual furnishing of the Knights Templar and the Rose Croix of the Scottish Rite [1:256]).

This leaves a bird at the bottom and a stylized cross of some occult kind in what appears to be an egg in the top left-hand corner. Perhaps the winged creature is simply one of the angels in ceremonial magic. Given the thick overlay of Royal Arch and Templar/Scottish insignia uncovered thus far, however, something Masonic rather than occult seems more likely, such as a dove, a prominent symbol in an honorary degree in the United States only known as the Ark and Dove.30 The dove is also the emblem of so-called androgynous lodges (those that include women, such as the French Knights of the Dove [1:533]). The triple cross inside the egg-shaped circle is probably both magical and Masonic in derivation. A triple cross serves as the signature of a Sovereign Grand Commander, or Thirty-Third-Degree Mason (1:5). The egg was an important symbol throughout antiquity, of course, and it is also of interest in the more arcane Scottish Rite. The symbolism of the egg in the esoteric or higher degrees in Masonry runs the gamut: it is a symbol of the magi, the Egyptians, good and evil, philosophy, the luminous God, the Supreme Intelligence in the World, the concavity of the celestial sphere enclosing all things, the world and its spherical envelope, the double power or the active and passive, and the male and female principles.31 “Agla,” at the bottom, is from the cabala and appears in the Master, or Third Degree of the Scottish Rite, as another name for God, there being three all told—Yahweh, Adonai, and Agla (p. 104).

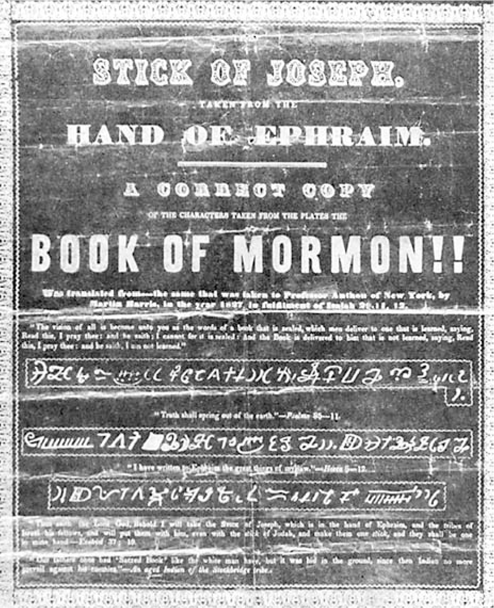

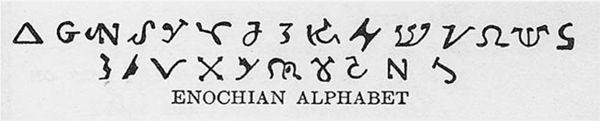

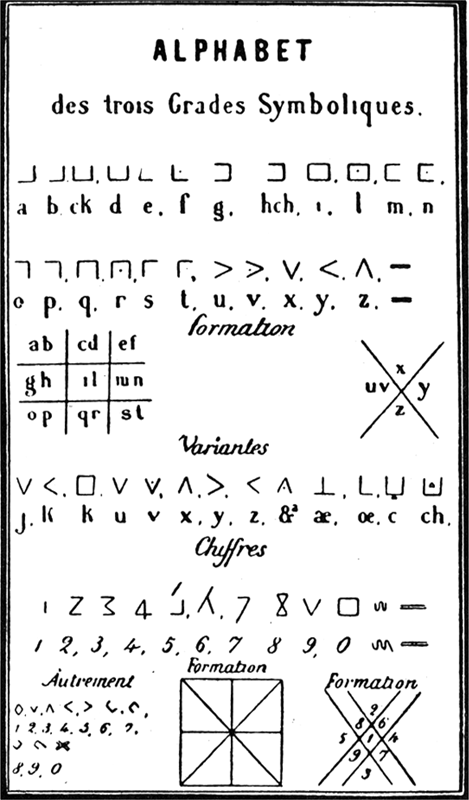

It seems entirely possible that the golden plates and the Smith family tracing board are one and the same. The only other clue as to what their characters may have looked like, written in so-called Reformed Egyptian, is an early advertisement (see figure 12). Its text might tell us a great deal if we could only read it, assuming the characters are not in some random order—a mere listing of an alphabet or cipher intended to have meaning only to certain readers in the know. When examined through the eyes of academe, the advertisement seems to consist of Greek and Latin, along with the odd Hebrew character, all of it written upside down or backward. But they may be a variant of the Masonic cipher known as the Enochian alphabet. In the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Degrees of the Scottish Rite, Freemasons are said to have accompanied the Christian princes to the Holy Land, fighting by their sides. There they discovered an ancient text written in Syriac and Enochian. Syriac, yes! But Enochian? Might Enochian be the Reformed Egyptian of the Book of Mormon shown in figure 12? The resemblance to the Enochian alphabet, courtesy of one Masonic encyclopedist (see figure 13), is striking, to say the least!

FIGURE 12 Early Mormon Broadside: A “Correct Copy” of the Book of Mormon Characters

James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1976), p. 49.

FIGURE 13 Enochian Alphabet

Robert I. Clegg, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (Richmond, Va.: Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply, 1966), 1:331.

FIGURE 14 Masonic Alphabet

Demeter Gerard Roger Serbanesco, Histoire de la Franc Maçonnerie universelle: Son rituel—son symbolisme (Paris: Editions intercontinentales, 1966), 2:212.

To suppose that the Book of Mormon characters reproduce the Enochian alphabet seems simplistic, however, for they are undoubtedly symbolic. In fact, it is possible to hazard a preliminary educated guess regarding the first three lines, a grab bag of Masonic emblems, Royal Arch and Scottish Rite ciphers, and, perhaps not surprisingly, some of the signs of the zodiac and the planets. It should come as no great surprise that the characters are almost entirely symbolic, the odd alphabetic ciphers being abbreviations for the Deity, the Christ as Logos, the Smiths, and, of course, young Joseph Jr., as a Mason of Christian and occult sensibility with a hidden adoptive agenda. But without the key—indeed the Mormon prophet himself—we can only hope to transliterate rather than translate per se.32

Should we ever find the golden plates and succeed in translating them for ourselves, the end result would no doubt prove a great disappointment. The text would likely not read anything like the English of the Book of Mormon. However, this could be because our sense of the written word and Smith’s could not be more different. Whether he squeezed his 588-page narrative out of a single family tracing board or the golden plates proper contained no more information than early advertisements for the Book of Mormon, there seems more than enough written text for a man of such aural-oral talent to spin a yarn of vast proportion.

There is a word in Masonry for adepts like Smith. Under the heading “Oral Instruction,” one Masonic encyclopedist discusses what he calls the “Bright Mason”: a student of Masonic esoterica, the so-called mysteries, who learns without the aid of books or written materials. The means by which such individuals acquire knowledge is thought to involve a purer form of communication and of passing down the wisdom of the ages from generation to generation. “Such of the legends as were communicated orally,” Oliver is quoted as saying,

would be entitled to the greatest degree of credence, while those that were committed to the custody of symbols, which, it is possible, many of the collateral legends would be, were in great danger of perversion, because the truth could only be ascertained by those persons who were entrusted with the secrets of their interpretation. And if the symbols were of doubtful character, and carried a double meaning, as many of the Egyptian hieroglyphics of a subsequent age actually did, the legends which they embodied might sustain very considerable alteration in sixteen or seventeen hundred years, although passing through very few hands.33

FIGURE 15 Rose-Croix Apron with Password “Pax Vobis” in Code

Erich J. Lindner, The Royal Art Illustrated (Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1976), p. 131.

PERHAPS THE BO OK OF MORMON represents a compromise between employing a pure oral transmission and breaking with esoteric convention and putting knowledge down on paper. Or the reference to Reformed Egyptian could be an allusion to the Degree of Scottish Elder Master and Knight of Saint Andrew, the Fourth Degree of Ramsay, which also goes by the name of the Reformed Rite. In any case, so the Mormon story begins, on a fateful spring morning in 1820, a young New York farm boy entered a grove of trees near his home to offer up his two cents on what could be done to avert disaster and save the republic as he conceived it. And after summoning the Lord of heaven and earth to his backyard, he resolved to attempt something visionary entirely his own.