DREAMING MASONRY: GETTING THE STORY PLUMB

And it shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions.

“Can they [the Mormons] raise the dead?” No, nor can any other people that now lives, or ever did live. But God can raise the dead, through man as an instrument.

IN HER SEMINAL Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, Jan Shipps argues that the story of Mormonism “began with the discovery of a book whose contents told Saints in the nineteenth century what had happened to the people of God who came to America before them in much the same way that the priests’ discovery in the recesses of the temple of a book said to have been written by Moses told the people in King Josiah’s reign about those who came to Israel before them.”1 She goes on to show how all the major events in the Mormon story recall the biblical narrative: the restoration of the Aaronic priesthood; the construction of a temple in Kirtland modeled after that of Solomon; Smith’s death at the hands of an angry mob, reminiscent of Jeremiah’s martyrdom; the crossing of the Mississippi and the trek to Utah, essentially a modern-day Israelite crossing of the Red Sea and journey through the wilderness; the arrival in Salt Lake City, an American land of promise and polygamy, a recapitulation of the stories of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. Absolutely! That said, the biblical narrative may not be the whole story.

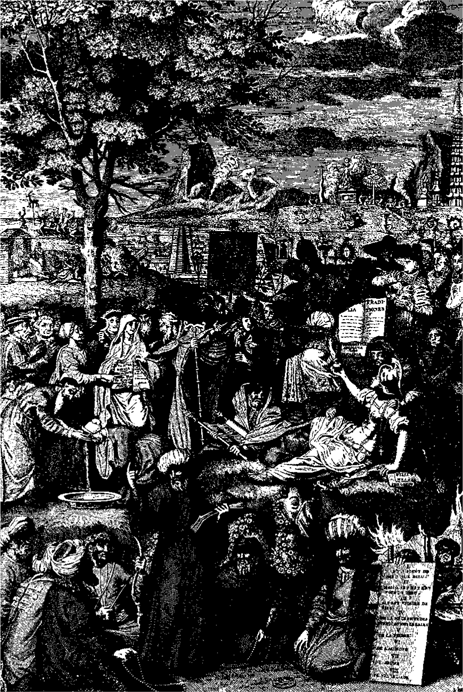

Smith and Finney tell their conversion stories using the same Masonic insignia. Retiring to a grove of trees and in the act of prayer, the men find themselves enveloped in darkness; neither could speak until a bright light burst on the scene and released them from bondage. Smith recalls coming to his senses sometime later, flat on his back and staring upward to heaven. One may compare this to the initiation of the Master Mason: blindfolded and not permitted to speak, the initiate must lie flat on his back and await the moment of release when the Grand Master takes him by the hand, lifts him up in an embrace known as the five points of fellowship, and, removing the blindfold, whispers the great mystery (the Grand Omnific Word) in his ear—hence the need for absolute discretion and secrecy (see figure 20).2 Darkness has a special place in Masonry. As Masonic authority Albert Mackey observes: “Freemasonry has restored Darkness to its proper place, as a state of preparation.” The aspirant, he explains, “was always shrouded in darkness as a preparatory step to the reception of the full light of knowledge…. The release of the aspirant from solitude and darkness was called the act of regeneration, and he was said to be … raised from the dead.”3

FIGURE 20 The Raising of a Master Mason

Erich J. Lindner, The Royal Art Illustrated (Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, 1976), p. 35.

A popular 1762 English exposé that appeared in America between 1790 and 1826 outlines the ritual and its impact on the aspirant. The blindfold, it explains, is intended to “throw” the mind of the candidate “into great perplexity.” When it is removed, the effect is dazzling: the brethren having formed “a circle round him,” the “glitter of their swords, and fantastic appearance” of their “white aprons” creates “great surprise.”4 The object is for the candidate to gain “knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ” and partake of the “divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world through lust” (pp. 16–17). The initiate, however, represents “one of the greatest men in the world, viz, our Grand Master Hiram,” King Solomon’s chief architect and Master Craftsman, not Jesus Christ per se.

The Master Mason induction ceremony originates in the story of the murder of Hiram Abiff at the hands of three renegade fellow Craft Masons (Jubela, Jubelo, and Jubelum).5 Refusing to divulge the secrets of Masonry before the completion of the temple in Jerusalem, Hiram pays the ultimate price. His murderers, not unlike Cain in the Bible, feign ignorance of their brother’s whereabouts, hiding the corpse “on the side of a hill.”6 They abscond but are soon discovered, their cries of anguish giving them away. There is some measure of honor, as the manner of their execution is dramatic: their tongues are ripped out, their hearts torn from their naked breasts, their bodies severed in twain, bowels burnt to ashes, etc., etc.—all at their own request. Following the grizzly spectacle, Solomon institutes a new ritual based on the life, death, and so-called resurrection of Master Mason Hiram Abiff (his badly decomposed body was lifted from a shallow grave and returned to Jerusalem in one piece). The concluding male embrace takes its name from the five points of fellowship: hand in hand, foot to foot, knee to knee, breast to breast, the left hand supporting the back. Another grand sign is adopted, consisting of the raising of one’s hands and exclaiming “O Lord, my God!” (p. 35). The secret grand word is then communicated to the aspirant in the loving embrace of his new Master.

Smith’s earliest recitation of the First Vision (1832) alludes to the Masonic emblems of sun, moon, and stars—the great luminaries that move under the watchful care of the All-Seeing Eye. “I looked upon the sun,” he writes, “the glorious luminary of the earth and also the moon rolling in their majesty through the heavens and also the stars shining in their courses and the earth upon which I stood.”7 The musical paraphrase, or ode, for the Master Mason degree speaks of sun, moon, and “planet’s light,” the latter referring to both stars and comets. Smith’s characterization of the earth as one of the heavenly luminaries can be seen as an extrapolation based on the ambiguous language in Masonic ritual: a single reference to planetary light might well lead one to include the earth in the same category as stars and comets.8

FIGURE 21 The Religions of the World “Masonry softens the asperities of conflicting opinions.”

Bernard Picart engraving, reproduced in Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John D. Yorston, 1911), 1:30b.

Smith credits one Bible verse in particular, James 1:5, with causing him to go to his Creator for private counsel. Smith’s object in going to his Lord, his query, and the Deity’s response all have a Masonic tone. “My object in going to enquire of the Lord,” Smith writes, “was to know which of all the sects was right, that I might know which to join…. I was answered that I must join none of them, for they were all wrong.”10 James adjures any who lack wisdom to “ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given.” It may be more than mere coincidence that the same passage serves as prologue for the Royal Arch Degree. “My son,” the Orator exclaims at the beginning of the initiation ceremony, “if thou wilt receive my words, and hide my commandments; so that thou incline thine ear unto wisdom, and apply thy heart to understanding; if thou criest after knowledge, and liftest up thy voice unto understanding; if thou seekest her as silver, and searchest for her as for hidden treasures, then shalt thou understand the fear of the Lord, and find the knowledge of God; for the Lord giveth wisdom; out of his mouth cometh knowledge and understanding.”9 James 1:5 is given special credence in the 78 Knights Templar initiation ritual as well and is read verbatim.11

The first lecture of the Apprentice Degree lauds the virtues of concord. Psalm 133 is read aloud: “Behold, how good and pleasant it is for the brethren to dwell together in unity!…” What follows underscores the necessity of unity and harmony: “For there the Lord of light and love, a blessing sent with power…. To live in love with hearts sincere, in peace and unity” (p. 20). The aspirant is counseled to avoid the company of factious persons and non-Masonic societies and then sworn to secrecy.12 Likewise, Smith is told not “to join with any of them [but not simply sectarian Evangelical churches]” and then placed under what seems a temporary gag order. “And many other things did he say unto me,” Smith explains, “which I cannot write at this time.”13

As the Mormon prophet tells his story, he apologizes for his adolescent peccadilloes, for “temptations, and mingling with society,” for frequently falling “into many foolish errors” and displaying “the weakness of youth and the corruption [later changed to “foibles”] of human nature” (p. 202). Smith simply claimed to be guilty of too much “Levity” and “Jovial company” inconsistent with his high and holy calling.14 An Apprentice in principle, on his way to becoming a Master Mason with heaven’s blessing, Smith held himself to the highest fraternal moral standards: temperance, fortitude, prudence and justice, morality being “the theory of the first degree.”15

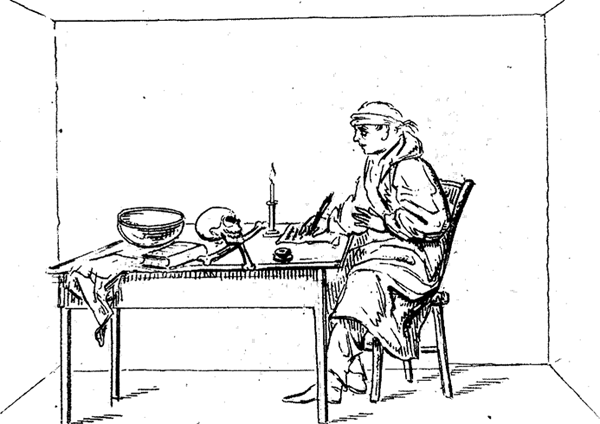

Smith’s visions move indoors at this point, from the sacred grove to his bedroom. This withdrawal to the bedroom can be seen as a Masonic “Chamber of Reflection” scenario, wherein aspirants ponder their eternal salvation in a humble parlor adjacent to the lodge prior to initiation (a gloomy, dark abode, the chamber exacerbated the feelings of despair requisite to advancing to the high and holy station of Royal Arch Mason and Knight Templar). The nocturnal visits of the angel Moroni become the new focus. At this point, the folklore of the higher (indeed highest) ritualistic echelons of American Masonry—that of the Royal Arch and Knights Templar Degrees—drives the story. In Royal Arch Masonry, Enoch (not unlike Smith) is said to have “a vision.” The Deity appears to him “in visible shape,” and Enoch is brought to his knees after “pondering how to rescue the human race from their sins and the punishment due to their crimes.” Enoch (like Smith) awakes and immediately goes “in search of the mountain he saw in his vision.” Not unlike the last of the Book of Mormon prophets, Moroni, Enoch constructs a series of vaults “in the bowels in the earth” and deposits “two deltas of purest gold, engraving upon each the mysterious characters,” as well as a “triangular plate of gold.” A “square stone” covers the aperture to the vault.16

Moroni’s attire may be Masonic, his white robe either the “white leather apron” and emblem of purity in Masonry or, more likely, the habit of the ancient Knights Templar—the latter befitting Moroni’s standing. Royal Arch “Captains” wear white and even carry a white banner.17 According to Masonic lore, Hiram’s “workmen” wore a “white garment” (p. 20). That Smith could see (into) Moroni’s bosom may allude to the one bare breast of the Master Mason initiate. In any event, Moroni’s skimpy attire, naked feet, and exposed bosom are consistent with the general drapery of the sublime Master Mason, Royal Arch Captain, and Knight Templar.

Moroni’s lectures, which occupy most of the night and part of the next day, are taken largely from the Old Testament—a series of Bible passages that Webb deemed particularly suited to Masonic uses: Malachi 3 and 4, Isaiah 11, and Joel 2.18 The first of these is pregnant with patriarchal possibility, recounting the eschatological Elijah’s role in turning “the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse.” In Malachi, too, are references to the Second Coming as “like a refiner’s fire,” the purification of the sons of Levi described as an alchemical-like purging of silver and gold. In Isaiah and Joel are prophecies of the gathering of a lost remnant of the house of Israel and a worldwide Pentecost of young men and women just before the great and dreadful day of the Lord.

Smith’s First Vision of the Father and Son in the sacred grove and then the nocturnal visitations of Moroni were, of course, not described in writing until many years after the event, the first such accounting in 1832. The official account suggests that Smith started having visions as early as 1820; he would have been only fourteen or fifteen. Three years passed before feelings of inadequacy and intense persecution caused him to seek out a second vision on September 21, 1823—which would make him seventeen at the time. They then occurred at the end of each year (on September 21 or 22, one presumes) for three more years before the golden plates were entrusted to his care, in 1827, when the Mormon prophet was still only twenty-one. It would be another three years before the Book of Mormon appeared in print.

FIGURE 22 The Chamber of Reflection

Avery Allyn, A Ritual of Freemasonry (Philadelphia, 1831), reproduced in Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 264.

There may be a degree of historical truth in this timeline despite the somewhat picturesque nature of the author’s writing. His story of the annual ministrations of an angelic being (the supernaturalism notwithstanding) could be seen as an admission that he studied under the tutelage of some (Masonic) luminary. (Smith’s belief that angels were corporeal beings who, contrary to popular mythology, did not have wings may be relevant here.)19 That Masonic initiates have a guide whose title suggests something rather otherworldly may also be pertinent, casting new light on the genus, if not the identity, of Moroni.

One thing is clear: Smith’s account of the First Vision does not contradict this. In 1820 he was old enough to have been a juvenile Knight Templar.20 (Adam Weishaupt’s infamous Bavarian Illuminati had so-called Nursery Degrees: Preparation, Novice, Minerval, and Illuminatus Minor [p. 143].) Perhaps in an attempt to pin a charge of atheism on Smith’s lapel, a neighbor of the Smiths later recalled that young Joseph was most certainly an active member of a local “juvenile debating society,” the sort of male association Palmyra’s snoopier Evangelical element would consider to be impious.21 We do not know nearly enough about the composition of the particular debating club to which Smith belonged; however, as Brooke argues in an essay appropriately entitled “Ancient Lodges and Self-Created Societies,” debating societies and other voluntary associations during the early national period and beyond had a significant Masonic presence and agenda, in some cases serving as a recruiting ground for future adepts.22 Moroni’s role resembles that of a Masonic “spirit guide,” aiding in a Royal Arch-like quest for buried treasure, “the summit and perfection of ancient Masonry.”23 Moreover, that the visitations took place once a year suggests Smith was pulling himself up by his own ritual bootstraps according to the old Scottish understanding—which required a period of not less than one year before graduating to the ensuing degree.

Be that as it may, the Royal Arch, Webb writes, “bring[s] to light many of the essentials of the Craft, which were for the space of four hundred and seventy years buried in darkness; and without knowledge of which the Masonic character can not be complete” (p. 121). The lecture part of the degree expounds the destruction of the Solomonic temple, the Babylonian captivity, the return of the exiles to Jerusalem, and their rebuilding of the temple. The aspirant reenacts the discovery of the lost book of the Law that the priests discovered in the recesses of the temple, as recounted in the Bible. “Often they were taken to a corner of the lodge,” Carnes explains,

and told to dig among the boards and stones representing the ruins of the first Temple. They would eventually discover a trapdoor, attached to the keystone of an arch, that concealed a darkened chamber below…. On the first descent he usually found three squares, which the High Priest said were the jewels of “our ancient Grand Masters—King Solomon; Hiram, King of Tyre; and Hiram Abiff.” On the second descent he discovered a chest “having on its top several mysterious characters.” Inside were a pot of manna, Aaron’s rod, and the “long lost book of the law.” The High Priest also uncovered several pieces of paper that together provided a key to the letters on the outside of the ark of the Temple.24

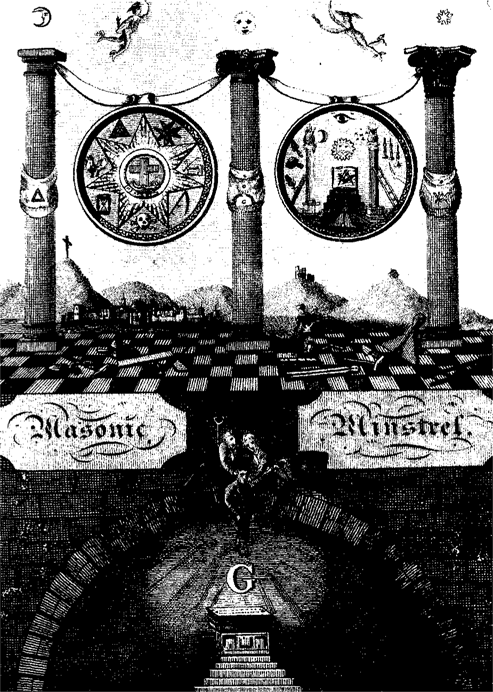

FIGURE 23 The Royal Arch Quest for the Golden Plate(s) of Enoch

David Vinton frontispiece (1816), reproduced in Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 267.

THE ODE FROM THAT RITUAL speaks of treasure brought forth from darkness to light, of a lost book whose “leaves are shining bright.”25 One may compare this to Smith’s 1838 account of the unearthing of the golden plates: “Under a stone of considerable size [keystone], lay the plates deposited in a stone box [vault]…. Having removed the earth [rubble of the temple], and obtained a lever which I got fixed under the edge of the stone, and with a little exertion raised it up [trapdoor], I looked in and there indeed did I behold the plates [lost Word of God], the Urim and Thummim [means of translating the mysterious characters] and the Breastplate as stated by the messenger.”26

The Mormon prophet would be forced to wait four long years before he could take the plates home and begin the arduous job of translation—not until his twenty-first year (Masonic age) and on September 22 (coincidentally, the date when the American lodges were supposed to open).27 He and scribe Oliver Cowdery would subsequently seek the approval of heaven, receive priesthood authority, first from John the Baptist, the patron saint of Masonry, and then from Peter, James, and John, the latter its other patron saint. With or without the permission or knowledge of the Grand Encampment of the United States, the Book of Mormon set out to prove that Smith and his following had acted in good faith and with Masonic power from on high.

NEPHI’S CONVERSION IN the Book of Mormon includes many of the same Masonic emblems, including a thinly veiled Masonic raising. Nephi, faithful son and devotee of his father, Lehi, nonetheless “groans” under the weight of “sins which so easily beset [him].”28 The Twenty-third Psalm, King David’s famous lament, is Nephi’s biblical inspiration, promising deliverance from sin. This psalm is a Masonic text of considerable importance and relevance, as it happens, used in the benedictions of the Most Excellent Master and Royal Arch Degrees.29 One can see why. David’s lying down in green pastures beside still waters, being led in the paths of righteousness for the Deity’s name’s sake, walking through the valley of the shadow of death, a rod and staff his only comfort, finding a table prepared in the face of his enemies echo the allegorical journey of the Freemason in the world. And Nephi’s religious awakening accords with that of the Mason’s journey in the world, the promise of salvation “out of the hands of [his] enemies” predicated on first wandering in the wilderness of one’s moral “afflictions.”30 Not unlike Smith, Nephi is bound by an oath of secrecy. “And mine eyes hath beheld great things; yea even too great for man,” he explains, “therefore I was bidden that I should not write them” (p. 107).

Like the Mormon prophet, Nephi labors under the weight of a less-than-perfect life before his epiphany. Questioning his standing in the eyes of God, he pleads, “O Lord, wilt thou not shut the gates of thy righteousness before me,” and then reassures himself precisely as Smith does, paraphrasing James, “Yea, my God will give me, if I ask not amiss” (pp. 70–71). This is also the plaintive cry of the Entered Apprentice at the door of the lodge as he awaits his turn to travel the narrow, ritual path of male moral rectitude. Nephi is greatly burdened by “temptations of the flesh” that “doth easily beset [him].” On this count, too, he is an excellent candidate, erring on the side of moral hypersensitivity. Nephi’s salvation is equated with freedom from the “sins of the flesh,” the hope and prayer of the Entered Apprentice, who also partakes of the “divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world through lust.”31 The first question the Entered Apprentice must answer is that which Nephi discusses, namely, in whom one should put one’s trust. The correct answer in the Masonic ritual is “in God”—Nephi’s response as it happens. “O Lord, I have trusted in thee, and I will trust in thee forever. I will not put my trust,” he goes on, “in the arm of flesh; for I know that cursed is he that putteth his trust in the arm of flesh.”32

Nephi criticizes his older brothers, Laman and Lemuel. They are immoral men, at bottom. Nephi’s attempt at moral suasion only confirms them in their latent carnality. Laman and Lemuel will grow to hate Nephi and attempt to take his life, forcing him to flee with his family into the wilderness. The people of Nephi build a temple “after the manner of Solomon.” The resemblance between Nephi and Hiram Abiff is uncanny, the Nephite temple in the New World a Masonic revitalization in the nature of the Solomonic recension that gave us Craft or Master Masonry (p. 72).

Lehi, Nephi’s pious father, can be seen as the first Grand Master of this ancient American Grand Lodge, although he lives just long enough to give it his blessing. This Masonic investiture and passing of the baton takes place when Lehi gathers his sons together one last time to bear testimony of the truth of the Gospel before he passes on to the next world. One is reminded of Jacob of Old Testament fame, who likewise blessed his posterity as a final act of patriarchal pedagogy (Genesis 49). Lehi’s awakening, thickly inscribed with Masonic emblem, is the “new” Masonic standard.33 He prefaces his remarks with a Masonic-like salutation to the Creator, underscoring his belief in “the greatness of God” and “the righteousness of [the] Redeemer” (p. 62). Belief in the Deity, Lehi opines, is fundamental to human existence, for “if there is no God, we are not, neither the earth: for there could have been no creation of things, neither to act nor to be acted upon; wherefore all things just have vanished away” (p. 64). He proceeds to rehearse the details of his wondrous vision of the “Tree of Life” that had kept them out of harm’s way and might change all their lives for the better.

Lehi’s visions in the Book of Mormon have too much in common with the dream world of Smith’s father to be mere coincidence. Psychologist and historian C. Jess Groesbeck traces the origin of Mormonism to the Smiths’ front step via this dream world.34 Mormonism, he declares, hoped to mend broken hearts and reunite a divided Smith household. However, ever since Lucy Mack Smith recounted the details of the elder Smith’s dreams in a controversial biography entitled Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet and His Progenitors for many Generations, critics have stressed the utterly natural, indeed familial origins of the First Vision and the discovery and translation of the Book of Mormon. This might be the whole story were it not for a second, less-known fact: Joseph Sr.’s dreams, Lehi’s vision of the Tree of Life, and the so-called Journey of the Freemason in the World seen to be one and the same.35 If so, Mormonism had high hopes of a fraternal reconciliation of a more widespread kind. Indeed, the elder Smith’s night visions come straight from the lodge. We know that he became a member of the Masonic lodge at Canandaigua in 1817, and his (Masonic) dreams followed closely on the heels of his induction. While the plethora of psychohistorical interpretations of Mormonism that accuse his namesake of either extreme narcissism or some bipolar disorder may be quite right, the dream world of the Smiths may not require the services of a good psychiatrist after all.

The elder Smith had several dreams in the years leading up to the discovery and translation of the golden plates and publication of the Book of Mormon. In one, he stumbles upon a box and eats its contents before being compelled to “drop the box, and fly for [his] life.” In another, he wanders a barren field aimlessly until he discovers “a narrow path … beautiful stream of water … a rope running along the bank” and beyond a “very pleasant valley, in which stood a tree such as [he] had never seen before.” In this dream, opposite the tree whose fruit is delicious and “white as snow” stands a “spacious building” filled with contemptuous but finely adorned persons of social standing. They can do no better than ridicule the righteous few gathered around the Tree of Life in the valley below. A spirit guide explains that the building is “Babylon,” hence its occupants “despise the Saints of God because of their humility” as a matter of course.36

Lehi has a vision of the Almighty, who descends “out of the midst of heaven … his luster … above that of the sun at noon-day.”37 Not unlike the elder Smith, he, too, is given a book but told to read it and has a vision of a fruit tree of renown. The same obstacles must be overcome before partaking of the fruit: rivers of filthy water, smoke, forbidden paths, a tall and spacious building catering to one’s most base desires. In Lehi’s dream, an iron rod guides the faithful on their way. In Joseph Sr.’s, it is a rope.

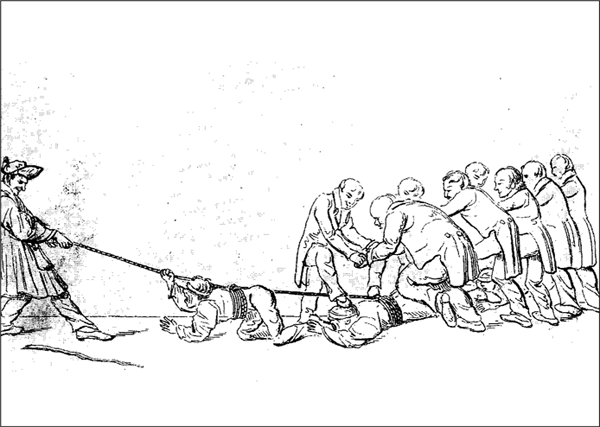

FIGURE 24 The Trials of Life

Avery Allyn, A Ritual of Freemasonry (Philadelphia, 1831), reproduced in Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 271.

Importantly, the garden scenes in the elder Smith’s dreams and in the Book of Mormon take place in the more democratic, liberal English gardens of the Enlightenment “in which the architecture of the landscape,” as Scott Abbott explains, “was intended to reflect and inspire moral, naturally human, non-absolutist pattern.” Following the belt-walk, or circuit, of an English garden, Abbott points out, “the initiate was meant to undergo a moral education.”38 Lehi’s “iron rod” may well allude to the English belt-walk, both serving to guide visitors along the right path. An 1831 depiction of the Royal Arch “trial of life,” however, shows three blindfolded initiates holding firmly to a taut piece of rope as they run the gauntlet and thus test their moral resolve. Or the iron rod might be a reference to the Masonic plumb line that “admonishes us to walk uprightly in our several stations before God and man.”39 Since the Book of Mormon identifies the iron rod as the Word of God, the Mark Master Degree becomes another possible source, since the “Line” or fifth emblem of Masonry “direct[s] our steps to the path which leads to immortality.”40 The 1st emblem, the “Sacred Volume,” also directs one’s steps (p. 38). Finally, the idea in the Book of Mormon of “holding to the rod” might refer to the rule of the Grand Master, which is compared to a “rod of iron.”41

FIGURE 25 Journey of the Freemason in the World (Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, ca. 1830)

Scott Abbott, Fictions of Freemasonry: Freemasonry and the German Novel (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), illustrations.

In the Scottish Rite (which runs in tandem to the Royal Arch), the circuitous path that the Mason must follow meanders along a raging river that one swims as a test of moral resolve. (The Book of Mormon counsels against this.) Smoke and fire obscure one’s vision from time to time. In one depiction of the Scottish Rite from around 1830, a large and spacious castle appears opposite a small grove of trees where a banquet of some kind is being served. In the middle stands the acacia, a fruit-bearing tree like that in Lehi’s dream. The “sweet Acacia” (acacia farnesiana), as it happens, is not only native to the southwestern United States but known for its extremely fragrant and beautiful floral decoration. The fruit of the Tree of Life in Lehi’s dream is likewise “most sweet, above all that [he] ever had before tasted.”42

In Nephi’s greatly expanded version of the same dream, an angelic messenger explains that the tree represents “the Lamb of God” (p. 25). Past Master and Masonic apologist par excellence Arthur Edward Waite explains that the acacia, or Tree of Life, in Masonic lore “signifies simplicity, innocence and the mind turning from evil, as if with instinctive horror.”43 (In Masonic parlance, the phrase “The Acacia is known to me” denotes one’s status as a Master Mason.) “In the Third Symbolical Grade, according to the classification adopted by the MASONIC ORDER OF MEMPHIS,” Waite comments, “the Worshipful Master explains that ‘the Branch of Acacia … is an emblem of that ardent zeal for truth which should be cherished by every Master, encompassed as he is by corrupted men who betray it’” (1:2). A Masonic source closer to home, in Aurora, New York (just thirty-two miles southeast of Palmyra as the crow flies), propounds a Christocentric interpretation of the Tree of Life that is reminiscent of that in the Book of Mormon.44 In the Knight of the Sun, or Twenty-eighth Degree of the Scottish Rite, the acacia symbolizes “the resurrection and immortality,” closely related to the Word.45

The other striking feature in this allegory is the time devoted to the Virgin Mary. The Book of Mormon is almost Catholic in its reverence for the mother of God. “And I beheld the city of Nazareth; and in the city of Nazareth I beheld a virgin, and she was exceedingly fair and white,” Nephi writes.46 This slip is often cited as proof by Evangelical critics of Smith’s ignorance of the Bible, Bethlehem not Nazareth being the place of the nativity. None, however, stop to think about how this contradicts the conventional wisdom that Smith was the product of a biblical culture and Protestant upbringing. It does jibe with the Degree of the Rosy Cross, wherein Nazareth is a significant word and denotes Jesus’ place of origin.47 Moreover, that the Book of Mormon should speak so glowingly of the blessed Virgin (on par with its admiration for Jesus of Nazareth) seems to go against the Evangelical grain, though it is perfectly consistent with the Templar reverence for the Mother of God.

A French order calling itself “Forest Masonry” may shed some light on the question of why Smith’s first revelations, if they are Masonic, were outdoors. As Clegg explains, though not necessarily connected to Masonic fraternity, they accepted both men and women and met outdoors when they could, decorating their lodge to resemble as much as possible a wooded glen (1:26–32, 353). That the conversion experiences of both Smith and Finney seem to employ many of the same Masonic tropes, but of the covertly adoptive and androgynous kind, speaks volumes. Both men seem equally interested in a more open and inclusive form of worship. Finney will let his heart guide him to a full and rich life of evangelical ministry, whereas Smith (more or less as he tells us) was unsuccessful. He failed to find in the outdoor and inclusive spirit of Evangelical revival a vehicle for male empowerment—albeit one that does not exclude women—instead, it seemed obvious to him from the start that most revivalists preached with female converts in mind. Smith, in hoping to correct this oversight, perhaps went too far the other way—at least in the Book of Mormon. His intention was to craft a sermon that did not exclude women, but it speaks rather too forcefully and singularly to men.

Lehi’s counsel to his wayward sons, Laman and Lemuel, can be seen as more Masonic analogue. “Awake from a deep sleep,” he admonishes them, “even from the sleep of hell, and shake off the chains which bind the children of men, that they are carried away captive down to the eternal gulf of misery and wo.” He goes on to tell them that “the Lord hath redeemed [his] soul from hell,” that he beheld “his glory” and was “encircled about eternally in the arms of his love.” As we will see, whenever Lehi or others in the Book of Mormon talk of the hellfire awaiting the wicked, it is not that of orthodox Protestantism: it is Masonic hellfire to which Lehi alludes, in short, the eternal sorrow that comes from ignorance of the male mysteries. Moral man dare not go it alone. Such statements have a Calvinist ring to them. Perhaps they are Calvinist. The important point is that such existential doom and gloom is not entirely foreign to Masonry, either. In the lecture portion of the Royal Arch Degree, the initiate is reminded that men are “frail creatures of the dust, offending against his most holy will and word, yet the adopted children of his mercy.”48 Indeed, his description of the Fall of Adam “and the dreadful penalty entailed on all his posterity” (p. 103) are not only Lehi’s final words of counsel to Laman and Lemuel but the last bit of moral advice in the Royal Arch Degree: “We can do no good or acceptable service,” it says, “but through him, from whom all good counsels and just works proceed, and without whose aid we shall ever be found unprofitable servants in his sight” (p. 103). The Book of Mormon comes very close to quoting this verbatim: “If ye should serve him with all your whole soul,” it says, “and yet ye would be unprofitable servants.”49

What soon becomes clear is that whether praising Nephi or admonishing Laman and Lemuel, Lehi’s fondest wish is that his sons become men of Masonic sensibility. “Arise from the dust, my sons,” he lovingly exclaims, “and be men, and be determined in one mind, and in one heart united in all things, that ye may not come down into captivity; that ye may not be cursed with a sore cursing; and also that ye may not incur the displeasure of a just God upon you, unto the destruction, yea, eternal destruction of both soul and body” (p. 61; emphasis mine). Lehi’s final words are not simply the ruminations of an Old Testament Jacob but that of a Grand Master—in this case, a homily usually read at investiture ceremonies and the granting of Masonic dispensations or charters. Lehi as Grand Master has every right to organize new lodges and grant dispensations, respectively.50 His sermon in the Book of Mormon and the lecture of the Grand Master at investiture proceedings both touch on “the most important problems of human destiny”—quoting Grand Master Rob Morris—such as “death, interment, the resurrection of the body, and the immortality of the soul … rationally applied to the present improvement of the heart” (p. 284).

In 1830 Smith published the history of a people who had started a Grand Lodge on American soil centuries earlier with God’s help and yet of their own accord. He had in the Book of Mormon a fictive Masonic “legal precedent,” to be sure, but more important a template for a widespread patriarchal retrenchment movement. The fact that his First Vision accords so perfectly with the visions of Lehi and Nephi in the Book of Mormon and that all this has a Masonic subtext suggests that Mormonism did not fall far from the acacia.

That said, the Book of Mormon attacks secret societies. A yarn spun by a disgruntled Masonic insider rather than an Evangelical outsider, it takes two parties to task: Masonry for the grisly murder of Morgan and Evangelical anti-Masonry, too, for grandstanding and political avarice. The notion that the book was meant to castigate Masons from top to bottom is due to the assumption that a band of political anarchists in the Book of Mormon, the “Gadianton Robbers,” are Masons in skimpy antique dress.

“LIKE THE MASONS,” Fawn Brodie writes, “the Gadiantons claimed to derive their secrets from Tubal Cain.”51 Brodie confuses Cain, the titular head of the Gadianton band in the Book of Mormon, with Tubal-Cain—a descendant of Cain through Lamech (Genesis 4:22). Tubal-Cain does not appear anywhere in the Book of Mormon.52 The name has Masonic significance, to be sure: it is a password in the Master Mason initiation ceremony.53 Mackey explains, “Tubal Cain has been consecrated among Masons of the present day as an ancient brother. His introduction of the arts of civilization having given the first value to property, Tubal Cain has been considered among Masons as a symbol of worldly possessions.” But Masonry does not claim descent from him, and most assuredly not from Cain! Again, Mackey explains:

The legends and truths which were transmitted pure through the race of Seth, were altered and corrupted by that of Cain, and much confusion arose in consequence of the frequent intercommunications of these two races before the deluge, though the truth would still be understood by the faithful. Of these was Noah … enabled to distinguish truth from falsehood, and to transmit the former in a direct line … through Shem…. Hence Freemasons are sometimes called Noachidae, the descendants and disciples of Noah. But Ham had been long familiar with the corruptions of the system of Cain … and after the deluge he propagated the worst features of both systems among his descendants, out of which he and his immediate posterity formed the institution known, by way of distinction, as the Spurious Freemasonry.54

THE NEPHITES, the protagonists in the Book of Mormon, are Noachites (the two even sound a little alike), through Shem, whereas the Gadiantons and their Lamanite sympathizers descend from Cain, either literally or by adoption.

The Book of Mormon does not impugn the character of Masonry per se when it chronicles the undemocratic activities of the Gadiantons. Such criticism can only have been intended for apostates and enemies of the order. In Waite’s New Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, he discusses the Masonic legend of the “Assassins and Anseyreeh.” Like the Gadiantons, they constitute “a confederated murder-system,” reside in the mountains, favoring the dagger as their weapon of offense, and perpetrate political murder and coups d’état by first “winning confidence.”55 The Assassins are related to the Thuggee, a Hindu and Moslem secret society believed to have constituted a worldwide network of spies, a cause célèbre in England in 1799 and again in 1826—ironically, the year of Morgan’s abduction. Thugs worshiped the goddess Kali. They had their own degrees, and their rituals include magical circles, hieroglyphics, and covenants to destroy the human race (1:28–33). The Knights Templar are the archenemies of all such secret combinations, the posterity of Ishmael, and the so-called Saracen hordes, who will occupy Jerusalem and eventually exterminate the Templars. The Gadiantons, can be seen as Masonry’s legendary assassins. The Nephites and Gadiantons battle it out in the narrative as veiled Christian Knights and Saracens, respectively, the former falling to the latter in a final battle to the death.

Even with no other clues, Smith’s use of the word “excitement” to describe his enemies and the sectarian climate that gave impetus to his religious awakening gives him away. Masons used “excitement” as a pejorative to describe their Evangelical enemies in the Antimasonic Party. This suggests that Smith’s epiphany should probably be dated no earlier than 1826.56 The important point is not the date of his religious awakening, however, but that the language of the First Vision can be seen as that of a Masonic sympathizer of some stripe in the wake of the Morgan affair. Revivalism per se is not the target of his vitriol, but rather the rancor of Evangelical anti-Masonry. “The theme of excitement,” Bullock explains, was “the cornerstone of [the Masonic] attack on Antimasonry.”57 Defenders of Masonry attempted to explain away the Morgan affair as not unlike the popular excitements and delusions that had ended Socrates’ and Jesus’ lives, at bottom the kind of popish plot that had resulted in the massacre of righteous men from time immemorial.

Likewise, Smith’s use of “secret combinations” vis-à-vis the Gadiantons can be seen as Masonic, an epithet for Evangelical anti-Masonry at the time. William Ellery Channing, America’s premier Unitarian, spoke out against the Antimasonic Party in 1829, describing it as “the principle of combination” that sets out to “spread one set of opinions or crush another.” He was particularly critical of the way Evangelicals used the “various and rapid … means of communication” to great effect.58 Masons accused Evangelicals of bombarding the public with a single, overarching idea—whether true or not. Truth be told, the Antimasonic Party waged a very effective, modern-style political campaign, and Masons merely begged them to exhibit some grace, if not tolerance—to no avail.59 Each hurled a wide array of extremely unflattering names at the other. But as a rule Masons, not Evangelicals, used the phrase “secret combinations” to describe and ridicule their enemies.60 Masons described the Antimasonic Party as “desperate fanatics [who would] drench this land of freedom with the blood of its sons! And for what? Office, office!”61 The Book of Mormon makes a similar point: “Whatsoever nation shall uphold such secret combinations, to get power and gain, until they shall spread over the nation,” it warns, “behold, they shall be destroyed, for the Lord will not suffer that the blood of his saints, which shall be shed by them, shall always cry unto him from the ground for vengeance upon them.”62

The polemic in the Book of Mormon takes issue with the smear tactics of its opponents. For example, those in Lehi’s vision who mock and point their fingers cause some to feel “ashamed” after partaking of the sweet fruit of the Tree of Life. Might this be a veiled critique of the Antimasonic Party’s militant propagandizing? We get some sense of the hurt the Antimasonic Party caused men of Masonic sensibility when the Book of Mormon describes the Jaredite voyage to the promised land: “And thus they were tossed upon the waves of the sea before the wind. And it came to pass that they were many times buried in the depths of the sea, because of the mountain waves which broke upon them, and also the great and terrible tempests which were caused by the fierceness of the wind.” In the story of the Jaredites, the enemies of righteousness are savvy media types, very good with words and able to manipulate the public mind. Jared, the son of Orner, “did flatter much people, because of his cunning words until he gained the half of the kingdom” (pp. 548–549). In fact, the Book of Mormon repeatedly blames the downfall of the people of God on slick politicking, smooth-talking carpetbaggers and scalawags of one sort or another. Such disturbers of the peace are also called “Anti-Christs,” another bit of Masonic name-calling and cipher for Evangelical anti-Masons. The so-called Anti-Nephi-Lehis are Lamanite converts and thus another jab at the Antimasonic Party.

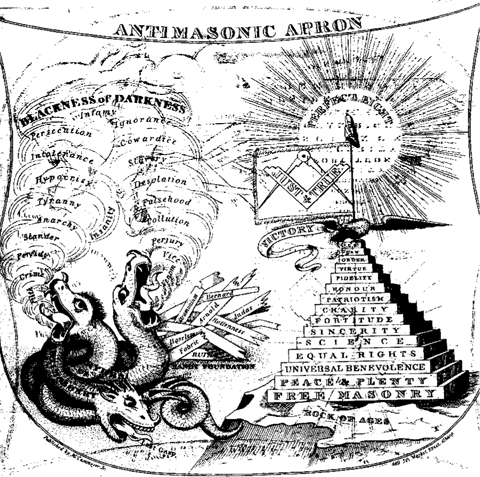

FIGURE 26 Anti–Anti-Masonic Polemic, Albany, New York, 1831

Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 305.

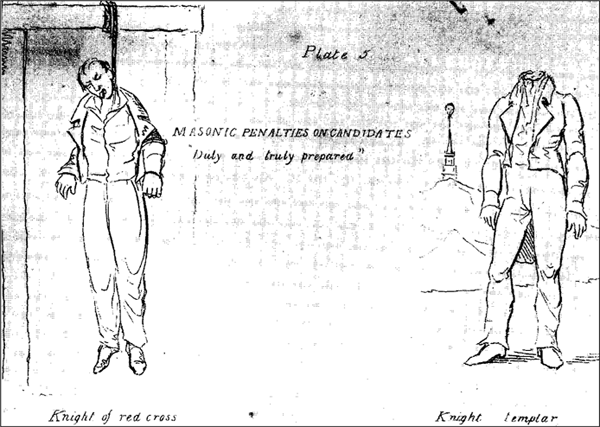

FIGURE 27 Masonic Penalties on Candidates

Avery Allyn, A Ritual of Freemasonry (Philadelphia, 1831), reproduced in Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 300.

E. Cecil McGavin’s Mormonism and Masonry implies that the Book of Mormon may have intended to malign the gentleman class of Freemasonry by an “ancient” linkage to Cain.63 Indubitably! Thus Brodie was not entirely wide of the mark to have seen the Gadiantons as an attack directed at Masonry. Yet she would have done well to consider that Lamanite converts and Nephites are Masons of the Noachite kind, with their Lamanite enemies being Spurious Masons and thus adopted into the lineage of Cain. The Book of Mormon does not distinguish between Spurious Masonry and Evangelical anti-Masonry in the final analysis, purposively confusing them as part of a two-pronged attack against religious elitism generally. To be sure, both threatened to undermine the hegemony of the pristine Nephite/Noachite (Royal) priesthood order.

Smith’s frustration mounted as he neared the end of his short life. On April 7, 1844, he used the occasion of the funeral of a friend to vent his spleen, exclaiming: “You don’t know me; you never knew my heart. No man knows my history. I cannot tell it; I shall never undertake it.”64 Short of coming out and saying unequivocally that his church was a new order of Knights Templar, it could not have been much clearer to anyone who knew their Royal Arch Masonry. In the 1830s, though, coming out and just saying this was certain to backfire in the heady days of the Antimasonic Party. And by the 1840s broaching the subject of Mormonism’s considerable debt to fraternalism might have destroyed the sense of mystery and uniqueness that had attracted adherents to the movement in the first place. To have been misunderstood on such a grand scale served his purposes. He complained bitterly, knowing better than clear up the confusion.

Looking back, it is hard to believe that not a single person knew (of) Smith’s (Masonic) history. His strong words that April morning may have been a throwing down of the gauntlet. Let any in the brotherhood accuse Smith of stealing their thunder, and he would give them what for. He was ready to face the music at long last, Masonic and/or Evangelical. The rejoinder from orthodox Masonic circles was swift and lethal. Storming the jail where he awaited trial proceedings for his part in the attempted murder of Lilburn W. Boggs, the governor of Missouri, Masons and Evangelicals alike riddled Smith’s body with shot as he attempted to escape through a window. Smith’s last words, “Oh Lord My God,” the sign of the Master Mason, had only egged them on. His executioners then erected a scaffold from which to hang the lifeless body of the Mormon leader. Cutting him down, they wanted to cut off his head—the ultimate Masonic disgrace and penalty—but were persuaded to leave well enough alone. Every one of his murderers was acquitted in legal proceedings that would have made the judge and jury in the Morgan trial blush. Meanwhile, America watched from the wings with no great sadness or compunction about standing idly by and letting the “men” settle this one. Smith was laid to rest in an unmarked grave, and his Masonic history died with him, the Book of Mormon buried in the same, soonto-be forgotten corner of the Lord’s vineyard in the century to come.