Willem Fourie

Introduction

The treatment of scars and adhesions cannot be described as a set modality. Treatment could rather be defined as a ‘management strategy’

using combinations of different massage and manual techniques to constitute a therapeutic approach aimed at improving tissue quality and mobility.

Techniques would include combinations of effleurage, petrissage, manual lymphatic drainage, fascial release techniques, fascial unwinding, friction techniques, myofascial release and more, and could collectively be called

‘scar tissue massage/mobilization/manipulation’.

Some sources trace the use of manual techniques in the treatment of wounds and scars back to one of the founders of modern surgery and pioneer in surgical techniques, Ambroise Paré (1510–1590), a French barber surgeon. He used, among other techniques, massage to relieve joint stiffness and promote wound healing after surgery on the battlefields (

http://www.therapycouch.com/MT.Theory.History.htm

). From these almost crude beginnings, the treatment and care of damaged tissue has grown into a management program based on better understanding of anatomy, physiology, pathology, tissue healing responses and available therapeutic modalities.

Extensive medical literature has been published on the subjects of tissue healing, scarring, adhesions and its development and prevention, but evidence to support the use of manual scar management remains inconclusive (Shin & Bordeaux 2011). Non-surgical techniques to help prevent and treat abnormal scars include laser therapy, intralesional agents, cryotherapy, radiation, pressure therapy, occlusive dressings, topical agents and scar massage. Although various scar massage techniques can be used, none has been validated to date. Their use is thus based on the experience of various teams and does not yet have scientific basis (Roques 2002, Atiyeh 2007). Although the concrete benefits of manual techniques on scars are hard to document, reported benefits include improved relationships with the patient, improved skin quality, relieved sensitivity, increased cutaneous hydration, improved scar quality, and better acceptance of the lesion by the patient (Roques 2002). Shin and Bordeaux (2011) also add hastening the release and absorption of buried sutures and aiding the resolution of swelling and induration as potential positive effects of scar massage (Shin & Bordeaux 2011).

Although scar management has been shown to produce positive results in patients, as many practitioners may have observed, there remains a major need for well-designed clinical trials that use objective criteria in order to establish evidence-based recommendations for or against the use of manual scar treatments in the care of surgical and other wounds.

This chapter offers an overview of principles involved in the planning and use of a scar tissue and adhesion treatment program. Wound care is a multidisciplinary process, starting with the acute phases under the care of a medical team, and continuing through various stages of rehabilitation and treatment of the damaged tissue, to full recovery. Many therapeutic disciplines will be involved in the program at different stages of the process. The rest of this chapter discusses the extent of the problem, background knowledge needed by the practitioner, how to evaluate and treat scar tissue, and methods for approaching special scenarios.

Overview

For normal day-to-day use sensation, mobility, stability and freedom from disabling pain and anxiety are

all prerequisites for quality of life. A failure within or breakdown of any of the above may compromise normal functioning, not only of the affected part, but may even influence function globally. The body is a functional unit – if one part is injured, the entire unit suffers. Maintenance of our well-being depends on the body’s ability to guide any injury through an appropriate sequence of repair, without complications.

Nature has given us a highly effective survival tool by restoring tissue integrity via granulation scar tissue in response to damage. While non-surgical tissue trauma such as infection, chemotherapy, radiation and cancer may damage tissue and initiate the healing cascade, a common trigger to tissue healing and scarring is still injury and surgery. Although all wounds pass through the same mechanism of repair towards full recovery, the final cosmetic and functional result may differ considerably. The ideal is for a scar to first close the wound and establish tissue stability; and secondly, to blend cosmetically with surrounding tissue, allowing for pre-injury function.

For open wounds (including surgical wounds) and severe internal tears (ruptured tendon or ligament), wound closure and tissue strength are critical and a certain amount of scarring is necessary and inevitable. When scar tissue fills defects in loose, flexible tissue, it will change to duplicate the same tissue characteristics as far as possible in the final stages of healing (Bouffard et al. 2008). Impaired mobility within loose, flexible tissue may contribute to chronic pain and tissue stiffness as well as abnormal movement patterns within the musculoskeletal system (see notes in

Chs 5

and

12

on the use, post-surgically, of eccentric loading during the remodeling stages).

What is the problem?

After an injury or surgery, successful healing of the part does not necessarily correlate with a return to full pre-injury/intervention function. A repaired tendon may develop normal tensile strength after surgery, but will be a functional failure if it does not glide within its tendon sheath. Similarly, a healed surgical incision on the surface with compromised movement between muscles, contracture of a joint capsule or adhesions between visceral organs may also be classified as functional failures – often ending in a dysfunctional unit. An important requirement for any post-injury or post-surgical management strategy is the maximization of function

without disruption of the wound healing and tissue repair processes.

The extent of the problem

Post-surgical scarring and adhesions result from injured tissue (following incision, cauterization, suturing or other means of trauma) fusing together to create abnormal connections between two normally separate surfaces of the body (Ergul & Korukluoglu 2008). Outcomes differ depending on the injured tissue, type of injury, genetic factors and the presence of systemic disease, and the impact on function may range on a continuum from inconsequential to debilitating with considerable clinical consequences. For example:

•

After a laparotomy, almost 95% of patients are shown to have adhesions at later surgery (Ellis 2007). Intestinal obstruction, chronic abdominal and pelvic pain and female infertility are also reported.

•

Previous abdominal surgery has been shown to be a factor in lower backache, myofascial pain syndromes (Lewit & Olsanska 2004).

•

Minimally invasive surgical procedures (e.g. arthroscopy) are reported as contributing to increased risk of developing knee osteoarthritis (Ogilvie-Harris & Choi 2000).

•

Previous surgical scars can be associated with surgical difficulties and postoperative complications in primary total knee arthroplasty (Piedade et al. 2009).

•

Adhesions, tissue fibrosis and loss of tissue glide between structures can be identified as the source of pain and restriction of movement and function in up to 72% of patients after surgery for breast cancer (Lee et al. 2009).

Not only do severe injury, aggressive surgery (e.g. cancer surgery) and burns potentially lead to a poor cosmetic outcome or disfigurement, but there is also a heavy economic burden on the medical care system. This could be as direct costs of care, or as future re-admissions and surgery as a result of the original procedure or injury. In the US, adhesion-related health costs exceed one billion dollars annually (ASRM Committee 2013).

A key problem is how to define and develop a sensible postoperative program to optimize final functional outcomes after injury or surgery. The development of such programs starts with an understanding of what a scar is, how it is formed, and its possible involvement in dysfunction.

A scar and adhesion strategy

Before one can start a treatment program, a therapist should first know and understand what he/she is aiming to achieve. The primary aim for a management strategy is the maximizing of function without disruption of the wound healing, repair and maturing processes.

What do we need to know?

To develop a scar and adhesion treatment strategy the following is essential:

•

Know your anatomy

•

Understand connective tissue and fasciae

•

Understand the concept of interfaces (this refers to an anatomic understanding of the tissue layers between the surface and the deeper layers of the body)

•

Know the entire healing process and its phases – from start to maturity and beyond

•

Understand the way tissue responds to injury and the healing outcomes – are you working with scar tissue, fibrosis or adhesions?

•

Understand the factors influencing the healing and repair process at different stages

•

A good working knowledge of massage and manual tissue techniques.

The anatomy of tissue layers

When palpating tissues, therapists will encounter a succession of tissue layers. Using the different characteristics of these layers such as hardness, density, texture and mobility, the therapist can distinguish between layers summarized below. For a full description of tissue layers, please refer to

Chapter 1

.

The body is arranged in several layers:

•

The

skin

formed by the epidermis and dermis

•

The

superficial fascia

consisting of two or more adipose, loose connective tissue layers separated by a membranous layer(s) of collagen and elastic fibers

•

The

deep fascia

that envelops the large muscles of the trunk and forms fascial sleeves in the limbs

•

The

muscle

and its

epimysial fascia

beneath the deep fascia of the limbs

•

The

peritoneum

is a thin layer of irregular connective tissue that lines the abdominal cavity. It further consists of two layers:

The

parietal peritoneum

as the outer lining of the abdominal cavity

The

parietal peritoneum

as the outer lining of the abdominal cavity

Visceral peritoneum

covering the viscera and organs contained therein.

Visceral peritoneum

covering the viscera and organs contained therein.

Concept of a tissue interface

All tissue layers and structures in the body need to move freely in relation to adjacent layers and structures. These could be areas of great mobility (e.g. the gliding of the skin or tendons, muscles and neurovascular bundles). These mobile layers can be referred to as ‘interfaces’. This is where movement takes place and restrictions (adhesions) may lead to musculoskeletal dysfunction. Guimberteau describes this as the fibrillar multimicrovacuolar collagenous system (Guimberteau & Armstrong 2015). This system consists primarily of areolar (loose) connective tissue and its fluid components (see

Ch. 1

). The integrity of this system is vital for movement quality.

Phases of wound healing

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to describe the healing process in detail. For detailed descriptions, refer to some of the references in this chapter (also see notes on wound repair in

Ch. 2

).

Scar formation is our primary method of restoring tissue integrity. All wounds, whether the result of surgery or trauma, progress through the same sequence and repair process, but may, however, vary markedly in the final cosmetic and functional result. Normal, uncomplicated healing and its time frames will be discussed.

Superficial wounds heal without scar tissue formation by simply regenerating the damaged epithelium. The healing of deeper wounds is an organized and predictable process consisting of three overlapping phases:

inflammation

,

proliferation

and

maturation/remodeling

(Myers 2012, Smith & Ryan 2016).

•

The first response to injury is inflammation, allowing the body to control blood loss and fend off bacterial invasion. It also recruits the cells needed to restore the injured area. This phase usually lasts from 48 hours to 6 days, depending on the extent of the damage. During this phase, the wound has no tensile strength and has a poor response to mechanical stress.

•

During the

proliferative phase

, new tissues are built to fill the gap left by damaged and debrided tissues. As a result, epithelial integrity is restored, and the wound is considered

closed

. This is an active healing phase starting from about day 5, reaching a peak around day 14 and lasting up to several weeks. There is now a slow increase in tensile strength with fibroblasts and collagen aligning along lines of stress.

•

Maturation and remodeling

starts at around day 21 and may last up to 2 years after wound closure. During this time scar tissue is reorganized from haphazard fiber arrangement to being oriented along the lines of tissue stress, until reaching maximum strength and function. During this phase tensile strength and mechanical behavior of the scar continue to improve (Lederman 1997). Unfortunately, even after remodeling, scar tissue is less elastic than the original tissue and may only achieve a maximum of approximately 80% of the original tissue strength (Myers 2012). A wound is considered

healed

after it is resurfaced, and has achieved maximal attainable tissue strength.

Different healing outcomes

‘Friendly’ scars close the wound, create stability, blend cosmetically with the surrounding tissue and allow structures to resume their pre-injury function. Problem or ‘unfriendly’ scars fall into two categories:

•

Failure to heal within the expected time frame due to the absence of inflammation, reduced inflammation (delayed healing) or chronic inflammation due to foreign bodies, malnutrition, infection, repetitive mechanical trauma or insufficient scar formation (dehiscence).

•

Excessive repair including hypertrophic scarring (overproduction of immature collagen),

keloids, or contractures (pathological shortening of scar tissue resulting in deformity; Myers 2012, Smith & Ryan 2016).

A scar

is the fibrous tissue that replaces normal tissues which a burn, wound, surgery, radiation or disease has destroyed (Andrade & Clifford 2008). Scar tissue is never as strong as normal, uninjured skin or tissue. It is what one sees on the outside (dermis/epidermis) and it does not have any functional use. It is there to plug the gap in the damaged tissue (Guimberteau & Armstrong 2015).

Hypertrophic scarring

is due to the overproduction of immature collagen during the proliferative and remodeling phases of wound healing. This is more likely to occur in wounds that cross the lines of tension in the skin, in wounds with a prolonged inflammatory phase (large or infected wounds) or in burns because of their lengthy proliferative phase (Myers 2012).

A

contracture

is the pathological shortening of scar tissue resulting in deformity (Myers 2012). The term ‘contracture’ is usually used to indicate a loss of joint range of movement as a result of connective tissue and muscle shortening. Underlying contracture formation are adhesions or excessive cross-links.

Adhesions/fixations

are related to the scarring process and develop secondary to the normal healing process. It is the process of adhering or uniting two surfaces or parts, especially the union of the opposing surfaces of a wound (

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary

1972). Unlike scarring, adhesions are characterized by a loss of mobility of tissues that normally glide or move in relation to each other (tissue interfaces) and, once matured, may even be stronger than the tissue to which they adhere (Lederman 1997). Adhesions can contribute to impaired muscle, joint and connective tissue integrity (Andrade & Clifford 2008). Secondary to an adhesion, a continuous state of mechanical irritation can affect many systems that are far removed from the involved site. The impact of the adhesion of normally sliding surfaces on normal organ or musculoskeletal function could range on a continuum from inconsequential to debilitating.

Fibrosis

is defined as the thickening and scarring of connective tissue. Fibrosis, as a process, is less linear than scarring, which typically occurs step by step in sequence. Fibrosis usually involves the connective tissues and structures of an entire region.

Factors influencing outcomes

Examples of factors (discussed in detail in Myers 2012) that may influence the rate of wound healing or change the outcomes of certain stages include:

•

Wound characteristics

such as the mechanism of onset, location, dimensions, temperature, wound hydration, necrotic tissue and infection

•

Local factors

include local blood circulation, sensation and mechanical stress in the wound area

•

Systemic factors

include age, inadequate nutrition, comorbidities, medication and behavioral risk-taking like smoking and alcohol abuse

•

Inappropriate wound management –

be aware of the patient/client’s possible use of home remedies or non-adherence to instructions

•

Clinician –

this includes inexperience (failure to recognize conditions requiring referral) or adherence to old customs and lack of knowledge.

Management protocols must be flexible enough to promptly recognize complications and risks in order to adjust the timing and application of therapeutic intervention.

How do we evaluate and treat?

Guidelines

The practitioner needs to keep two basic guidelines in mind during the evaluation and treatment of scars and adhesions. Touch needs to be graded and

it should be understood where and how tissue stops under one’s palpating fingers or hands.

Depth and grading of touch

An advantage of manual techniques is that the hand is a sensitive instrument which establishes a feedback relationship with the manipulated tissue. When treating wounds and scarring, the therapist should be clear of how deep and firmly to work. A grading scale of 1–10 could be used (Fourie & Robb 2009, Smith & Ryan 2016).

•

Grade 1 to 3:

Very light, mild and non-irritating. It can be compared to moving the eyelid on the eyeball without irritating the eye. No discomfort.

•

Grade 4 to 6:

Moderate to firm. This is where most massage techniques are performed. There may be mild discomfort, but with no irritation or damage to tissue.

•

Grade 7 and 8:

Firm, deep and uncomfortable pressure with discomfort, but is tolerable. Potential exists for tissue bruising. Trigger point work would be performed at this level.

•

Grade 9 and 10:

Deep, very uncomfortable or painful with a strong potential for tissue damage. It is often described as ‘surgery without anesthesia’. An example of this grade would be deep transverse friction.

The barrier phenomenon

Similar to joints, soft tissue has a specified range of available movement. Within this range of movement, normal soft tissue has three barriers, or resistances, that can limit movement – the physiological barrier, the elastic barrier, and the anatomical barrier (Andrade & Clifford 2008).

•

Physiological range is necessary for smooth, unrestricted movement of underlying structures during normal movement – it determines the available active range of movement.

•

The elastic barrier is the resistance one feels at the end of the passive range of movement when taking the slack out of the tissue (engaging the tissue).

•

The anatomical range (barrier) refers to where tissue can be stretched beyond the physiological range before coming to a stop without discomfort or pain (the final passive range of movement).

•

The distance between physiological and anatomical limits constitutes a ‘safety’ zone protecting the body from damage should external forces be applied.

At the physiological barrier minimal resistance to stretch or shift is encountered. When resistance is met with no further tissue movement possible, the anatomical barrier is reached. Under normal conditions this barrier has a soft, elastic end-feel and can be moved easily accompanied by a sensation that no unnecessary tension or pain is present in the target tissue.

In a

pathological

barrier, the anatomical (passive) tissue range is reached prematurely and occurs when soft-tissue dysfunction is present. This barrier characteristically has a tense, restrictive feel, with an abrupt, hard or leathery end-feel. Normal physiological movement may still be present with no apparent movement restriction, but there will be reduced protection when the tissue is strained. Restrictive barriers may occur in skin, fascia, muscle, ligament, joint capsule or a combination of these tissues (Andrade & Clifford 2008). Pathological barriers can limit available range of motion in tissue or alter the position of the mid-range, thereby changing the quality of available movement in joints or between structures.

Evaluation

Scar evaluation aims to determine the quality

, extent

and depth

of the ‘premature or pathological’ tissue barrier.

•

Quality

refers to the perceived

end-feel

– a normal soft, elastic or an abnormal solid, abrupt end-feel.

•

The

extent

of the barrier refers to

where

in the available range resistance is encountered, and the size of the involved area.

•

The

depth

of the tissue barrier may be subjective but an attempt should be made to distinguish between

which tissue layers

restrictions are felt: superficial between dermis and deep fascia, deep restrictions between muscles, organs or between a tendon and its sheath.

Assessment of fascial glide:

•

Skin and superficial fascia

– manually glide the skin

over

the deep fascia. Move hand and skin as a unit to the end of available tissue glide using a pressure grading of 2–4.

•

Deep fascia and myofascial interfaces

– move one deep structure

over

another. Change hand or finger position accordingly and glide tissue at a firm pressure grading of 4–6.

•

Deep muscle and soft tissue on bone interfaces

– modify hand and/or finger position to test for specific directional restrictions with fingertip or thumb pressure at a pressure grade of 6–8. Discomfort may be experienced by the patient and should therefore be done with care.

This is an assessment of tissue movement

, not of painful areas within the soft tissue. Palpation is for tissue mobility, flexibility and freedom of tissue glide. The position and direction of tight, hypomobile or inflexible tissue should be documented.

Assessment of scar movement:

•

Longitudinal

along the length of the scar

•

Transverse

across the long axis of the scar

•

Rotation

clockwise and anti-clockwise

•

Lifting

the scar vertically away from deeper layers.

Treatment

Treatment is guided by both the source

of a restriction and extent of the resultant dysfunction. Primary treatment is directed at the restricted tissue glide (local source of the problem) before rehabilitating the abnormal condition that the patient presents with (the dysfunction). Depth, site and extent of restricted tissue gliding should be clearly ascertained.

Principles

•

Treatment is directed at the mechanical restriction identified through evaluation.

•

The goal is to move the tissue barrier towards a normal end-feel and amplitude.

•

Treatment is approached in a layered fashion from superficial to deep; clearing one layer or compartment of restrictions before moving to a deeper or adjacent layer.

•

Techniques are performed at or just before the palpable tissue barrier at varying angles to the restriction.

•

Gentle touch grading is used during the early stages. For mature, chronically adhered scars more forceful treatment at higher touch grading may be necessary.

How to treat

To safeguard against wound breakdown and increased inflammation, gentle treatment should be used in the early stages of healing. However, when using higher touch grades for longstanding scars and adhesions, care must be taken to avoid triggering a new

inflammatory response.

Approaches to engage and move the tissue barrier (Lewit & Olsanska 2004) are as follows:

•

Engage the barrier directly and wait with a sustained pressure until the tissue releases and the barrier shifts after a short delay.

•

Use a sustained stretch of the scarred tissue. Stretch could be uni- or multidirectional.

•

Apply slow rhythmic mobilizations towards and into the tissue barrier. Movement direction could be perpendicular to, at an angle to, or away from the tissue barrier.

Manipulating tissues

There are many ways of effectively applying manual techniques in the treatment of troublesome scar tissue and adhesions. In reality only a limited number of ways of treating tissues exist, with most of the scar tissue treatment techniques being variations of these (Lederman 1997, Chaitow & DeLany 2008, Smith & Ryan 2016).

Variations of possible direct tissue loading approaches (from Chaitow & DeLany 2008) are:

1.

Tension loading

where traction, stretching, extension and elongation is involved. The objective is to

lengthen

tissue by encouraging an increase in collagen aggregation.

2.

Compression loading

to shorten and widen tissue by increasing the pressure thus influencing fluid movement. Compression not only affects circulation, but also influences neurological structures and encourages endorphin release.

3.

Rotation loading

effectively elongates some fibers while simultaneously compressing others. This produces a variety of tissue effects. ‘Wringing’ techniques or ‘S’ bends are examples of rotation loading.

4.

Bending loading

is in effect a combination of compression and tension with both a lengthening and circulatory effect on the target tissues. ‘C’-shaped bending or ‘J’-stroke movements are commonly employed.

5.

Shearing loading

translates or shifts tissue laterally in relation to other tissue. All techniques attempting to slide a more superficial soft-tissue layer

on or across

a deeper tissue layer or structure are included here.

6.

Combined loading

involves the combination of variations of all the loading approaches above leading to complex patterns of adaptive demands on the targeted tissue. For example, the multidirectional combining of a stretch with a side bend is more effective than either a stretch or a side bend alone.

Additional factors to consider include:

•

How hard? The degree of force being used (refer to grading above).

•

How large? The size of the area to which force is being applied.

•

How far? Refers to the amplitude of the applied force. At the beginning of the range, in the middle of the range, full range large amplitude, or at the end of the range small amplitude (refer to the barrier phenomenon above).

•

How fast? The speed with which the force is being applied – fast or very slow. The speed will influence pain and autonomic receptor responses.

•

How long? Could refer to the length of a treatment or the length of time a force is being maintained.

•

How rhythmic?

•

How steady? Does the employed force involve movement or is it static?

•

Active, passive or mixed? Is the patient active in any of the processes?

Basic techniques

Manual techniques used on scars and adhesions mostly have no prescribed style or sequence, but are based on the principles outlined above. The goal of

treatment is to loosen the collagen fiber linkages that have developed within the scar and the adherences between it and its surrounding tissues. Effective treatment applies direct pressure to specific points and directions of resistance, i.e. concentrating effective force on local areas

. For effective, concentrated force application, the therapist’s fingers or hand should not glide over the skin’s surface. No, or very little, lubrication should therefore be used.

Examples of basic techniques are listed below:

1.

Gross stretch (

Fig. 18.1

):

this is the most superficial scar technique using tension loading. Using finger or full hand contact:

Take up all the tissue slack.

Take up all the tissue slack.

Apply a gentle stretch along the length of the scar.

Apply a gentle stretch along the length of the scar.

Hold, wait for release and stretch again.

Hold, wait for release and stretch again.

Change hand position and repeat the stretch perpendicular to the original stretch.

Change hand position and repeat the stretch perpendicular to the original stretch.

Repeat the stretch sequence diagonal to the previous position.

Repeat the stretch sequence diagonal to the previous position.

Continue to stretch across the scar in a radiating pattern until no further stretch is possible.

Continue to stretch across the scar in a radiating pattern until no further stretch is possible.

NOTE

: this technique should only be applied along the length of the scar in the early phases of healing as perpendicular shearing forces should be avoided.

2.

Gentle circles (

Fig. 18.2

):

the fingers move the skin

over

the deep fascia. Tissue movement takes the form of an engaged shearing nature, combining tension, shearing and compression loading:

Rest the fingers on the part to be treated (next to the scar). The heel of the hand may rest on the body for better control (

Fig. 18.2A & C

).

Rest the fingers on the part to be treated (next to the scar). The heel of the hand may rest on the body for better control (

Fig. 18.2A & C

).

Starting at the 6 o’clock position, push the skin clockwise in a circle with the middle three fingers.

Starting at the 6 o’clock position, push the skin clockwise in a circle with the middle three fingers.

Figure 18.1

Gross stretch of the scar and surrounding tissue. (A) Stretching along the long axis – elongating the scar. (B) Gliding scar and surrounding tissue along the long axis. (C,D) Stretching in opposite directions. Extra care should be taken in immature scars.

Figure 18.2

Gentle circles next to or on the scar. (A) Circular movement with fingertips engaging the tissue barrier directly. (B) Two-handed circles stretching away from the scar and barrier. (C) One-handed circle engaging the barrier directly. (D) Gentle circles on the scar – moving the scar in a circular motion.

Slowly move the skin towards the scar to engage and shear the tissue barrier in a circular movement with even pressure and speed.

Slowly move the skin towards the scar to engage and shear the tissue barrier in a circular movement with even pressure and speed.

Change hand position, repeat the circle and release.

Change hand position, repeat the circle and release.

Treat the full length of the scar and repeat several times in a session if needed.

Treat the full length of the scar and repeat several times in a session if needed.

Alternatively, start the circle at the 12 o’clock position and pull away from the scar (

Fig. 18.2B

), or place the fingers on the scar (

Fig. 18.2D

) to move the scar over the deeper layers in a circu lar movement.

3.

Firm upside-down ‘J’ (

Fig. 18.3

):

similar to the previous technique in terms of starting position and depth. Tissue movement is of a combined loading nature:

Direct the stroke perpendicular towards the scar from about an inch (2.5 cm) away.

Direct the stroke perpendicular towards the scar from about an inch (2.5 cm) away.

Movement is slow, firm and deliberate into the tissue barrier.

Movement is slow, firm and deliberate into the tissue barrier.

When the barrier is engaged, the fingers shear away towards the left or right and the tissue is allowed to return to its non-stretched position.

When the barrier is engaged, the fingers shear away towards the left or right and the tissue is allowed to return to its non-stretched position.

Repeat until the tissue barrier has moved, or discomfort subsides.

Repeat until the tissue barrier has moved, or discomfort subsides.

This technique could be used very gently in early healing stages (

Fig. 18.3C & D

; touch grading 1–3), or firmly (touch grading 8) on mature scars (

Fig. 18.3A & B

).

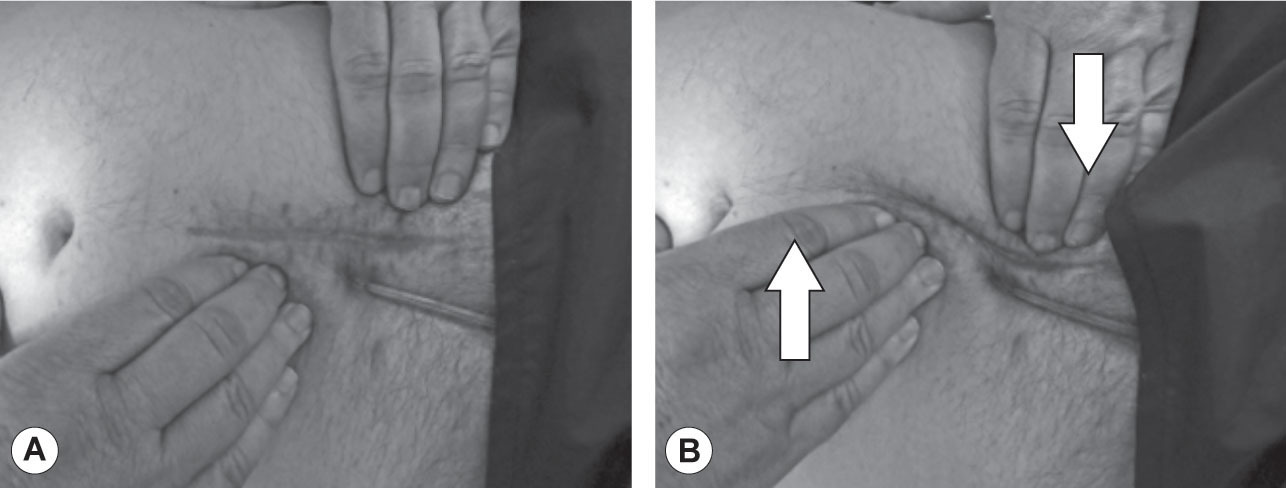

4.

Vertical lifts (

Fig. 18.4

):

vertical lifts are used to treat any scar that can be gripped between thumbs and fingers and uses tension loading.

Grip an area of the scar gently, but firmly.

Grip an area of the scar gently, but firmly.

Apply a vertical stretch perpendicularly off the surface of the body.

Apply a vertical stretch perpendicularly off the surface of the body.

Figure 18.3

Direct engagement and shifting of the tissue barrier – firm upside-down ‘J’ strokes.

Figure 18.4

Sliding towards and ‘under’ the scar, attempting to ‘lift’ the scar. (A,B) Sliding towards the scar and attempting to glide ‘under’ the scar. (C,D) Taking the scar between fingers and thumbs, attempting to lift the scar vertically away from the surface. This should be done gently with adherent scars.

Hold, wait for a release and increase the stretch.

Hold, wait for a release and increase the stretch.

Repeat the lift sequence from different angles until no further stretch is available.

Repeat the lift sequence from different angles until no further stretch is available.

5.

Assisted vertical lifts:

in cases where a scar is too sensitive, deep or has an extended surface (e.g. burn scars), manual lifting may be impossible. Here, ‘vacuum massage’ may be an effective alternative. It is a non-invasive mechanical massage technique performed with a mechanical device that lifts the skin by means of suction, creates a skin fold and mobilizes that skin fold (Moortgat et al. 2016). Suction grading can be carefully set mechanically depending on the stage of healing and severity of scarring and adhesions.

6.

Skin rolling (

Fig. 18.5

):

a tension loading technique used to treat restricted mobility of the skin and superficial fascia.

Using as broad a contact surface as possible, grasp the skin and superficial fascia between thumb and fingertips.

Using as broad a contact surface as possible, grasp the skin and superficial fascia between thumb and fingertips.

Lift the tissue and, while maintaining a stretch on the tissue, roll the superficial tissue along the surface in a slow wave.

Lift the tissue and, while maintaining a stretch on the tissue, roll the superficial tissue along the surface in a slow wave.

Glide the thumb or fingers along the tissue as you simultaneously gather and release tissue while maintaining the grasping and lifting motion.

Glide the thumb or fingers along the tissue as you simultaneously gather and release tissue while maintaining the grasping and lifting motion.

This technique can be used as an assessment, introductory technique, treatment or re-assessment.

7.

Wringing or ‘S’ bends (

Fig. 18.6

):

when used for scar or adhesion treatment, this is a modified petrissage technique using compression and shearing with varying amounts of drag, lift and glides repetitively to release and mobilize tissue.

An impairment-based approach is recommended for treatment of restrictive scars and adhesions, regardless of the modality used. The selection of technique, direction and depth of application, are based on the level of dysfunction revealed during the assessment. This approach gives the therapist the flexibility to adapt treatment to the person, rather than treating the ‘diagnosis’. Furthermore, treatment can be modified in line with the patient’s improvement or lack of progress based on the tissue response (Fourie & Robb 2009).

Figure 18.5

Skin rolling.

Figure 18.6

Wringing or ‘S’ bends.

Treatment is discontinued when the release has been completed in all directions and layers. This may not happen in a single treatment and may even take several months – especially in longstanding chronic scars. Care should be taken to avoid creating wound breakdown or an inflammatory response to tissue mobilization.

Are there special concerns?

Broad outlines and guiding thoughts on early wound massage, burns, breast scarring and the abdomen will briefly be discussed. At all times these special groups should be treated with consent from the patient and the supervising medical practitioner or medical team.

Early intervention

Intervention may start early after an injury or surgery. Treatment should progress with care as the inflammatory phase is dominant and the wound has no strength to resist straining forces. Dressings and sutures may be in place and some level of muscle spasm, pain and swelling (edema) may be present. The aims of treatment should be the control of edema and swelling and the prevention of potential adhesions while gently guiding the wound towards full recovery.

Inflammatory phase

Edema is part of the normal inflammatory response that occurs after injury and surgery and can be defined as excess fluid in the interstitial space (Villeco 2012). Such swelling may compromise the diffusion of waste and nutrients between the blood capillaries and the cells. During the inflammatory phase (days 2–6), edema is liquid, soft and easy to mobilize. This fluid should be managed through the principles of compression, elevation, cold, and gentle active movement. Gentle massage techniques to stimulate the lymphatic system proximal to the injured area may be used. No tissue barriers should be engaged or stretched and a touch grading of 3 should not be exceeded.

Proliferative phase

As scar production is accelerated during the proliferative phase (2–6 weeks), organized adhesions start to form between structures and edema, if present, becomes more viscous. The excess fluid is now called exudates (Villeco 2012). The wound is now closed, and there is a gradual increase in tensile strength.

•

Lymphatic massage and other techniques that stimulate an intact lymphatic system should be the focus of the therapy program.

•

Gentle techniques (as described above) engaging the subcutaneous layers can now be introduced, together with active motion and tendon gliding exercises to minimize adhesions between the developing scar and surrounding tissue.

Burn scars

Burn injuries cause destruction of the skin, as well as a host of other physiological changes that can affect every body part (Myers 2012). Skin thickness varies in different anatomical areas and individual burns are not uniform in depth. This may complicate classification of the degree of damage as well as the final selection of tissue mobilization technique. A single burn scar may have areas of partial thickness (epidermis and dermis) damage with minimal scarring, through to areas of full thickness (epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue) destruction with severe hypertrophic scarring. Differing degrees of damage will need individual intervention strategies and will vary greatly in final outcome.

Burn scars may need 6 to 24 months to mature. The scar tissue is fragile and prone to breakdown from friction, shearing, and trauma. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids are possible complications of the remodeling phase of burn wound healing (Myers 2012). Scar mobilization may help remodel scar tissue quality and appearance. More severe scars may benefit from more aggressive interventions.

Indication and aims of massage and manual intervention are:

•

Development of a good quality scar

•

Reduction or prevention of contractures from forming

•

Reduction of pruritus (itching)

•

Reduction of swelling – burned and grafted extremities commonly have lingering edema that can result in pain (due to compression on underlying structures) and joint stiffness

•

Pain reduction and management

•

Reduction of hypersensitivity of the skin

•

Treatment of the underlying soft tissues (i.e. muscles, fascia)

•

Prevention of dysfunction of compensatory patterns

•

Preparation of the tissue for stretching and strengthening exercises

•

Assistance in management of psychological symptoms.

Starting during the remodeling phase, scar tissue should be gently cleaned and a moisturizer should be applied to prevent dryness, cracking, and skin breakdown. This may result in better relief of itching, pain, and anxiety. Scar mobilization may further help remodel tissue quality and appearance. Gentle scar mobilization using a moisturizing agent may be used to help remodel scar tissue. These interventions may be started with care as soon as the wound is closed (Myers 2012). Care should be taken to limit shearing forces as blisters may occur if scars are exposed to friction or shear forces.

As scar tissue matures, techniques could be applied with more loading, greater amplitude and for longer periods as tissue allows. Techniques could include stretching, wringing, ‘S’ bending, ‘J’ strokes targeting specific tight areas, skin rolling and even careful friction-type tissue mobilizations. Monitoring scar tissue response to massage techniques (especially vigorous techniques such as frictions) is particularly important with burn scar tissue as it is compromised and can be susceptible to breakdown (Kania & Boersen-Gladman 2004).

Once matured, burn scars may still contribute to abnormal movement patterns and tissue tension in normal parts of the body for many years. Healthy muscle and fascia around and underneath a burn scar also need to be addressed. Spasms, tightness and

adhesions frequently happen due to damage from the initial trauma and tension on the surrounding tissue as the scar progresses through its healing phases. To alleviate this, a full selection of massage and fascial release techniques could be used.

Breast scarring

The breast is a glandular structure of the superficial fascia layer, separated from the deep fascia of pectoralis major by the retromammary space. It does not have active internal supports, such as muscles, and its fascial membranes take all the stresses of gravity and body movements. Further to this, breasts do not have usable planes of dissection, so surgical cuts have to be made bluntly through the tissues. As a result there can be a greater tendency for puckering and pulling as the scar dehydrates and contracts within its tissue host. There is also a greater tendency for large planes of adherence to develop within breast tissue itself, or adherence to the underlying pectoralis major muscle. This can lead to less compliant, more irritating types of scarring with established scars having a non-functional, matted fiber pattern.

A significant number of women may have lingering problems with edema, pain and uncomfortable scar formation, which can be aesthetically and symptomatically troubling (Curties 1999). Scar tissue in the breast may develop into a long-term pain focus, even after minor surgical procedures, such as a biopsy or draining a breast abscess. When there is an area of tissue scarring or adherence present, forces can be exerted unevenly through the neck and shoulder girdle.

Ideally, the therapist could begin working on optimizing fiber orientation once collagen deposition is well started but the scar has not consolidated (10–14 days). However, in the majority of cases the practitioner only starts treating the scar after it has become well established. Since breasts do not have inherent muscles, the exertion of ‘good’ directional forces do not occur. These forces help a developing scar to adjust its collagen fiber direction to the lines of force normal to the body part. Bras further tend to hold breasts tightly to the chest wall while their scars are forming. As a result, breast scars are very susceptible to spreading and bulging or, alternatively, to becoming strongly thickened and reinforced, with established scars having a non-functional, matted fiber pattern.

Aims of scar management on the breast or a mastectomy site are the same as for other body parts – reduction and control of edema and the re-orientation of collagen fibers within the scar. Treatment of scar tissue and adhesions should be aimed at firstly the breast tissue itself, and secondly at movement between breast and chest wall. Direct or indirect fascial techniques can also be employed to great effect. A less aggressive approach is advised to limit stresses on supporting fascial membranes.

Abdominal scarring and visceral adhesions

Almost all patients develop adhesions after transperitoneal surgery. Adhesions (a fixed connection between tissues which normally slide relative to each other) can form between viscera and/or intra-abdominal/pelvic organs. Adhesions between omentum and the wound are most common (Van Goor 2007). The normal range of motion of the tissues is inhibited by the abnormal relations of the visceral (or other) fascia, potentially disrupting the proper physiological functioning of the organs (Hedley 2010).

The circumstances which give rise to the adhesion of normal sliding surfaces are multiple and include the following causes:

•

Inflammation from infections or other types of disease processes

•

Inflammation and scarring caused by surgical intervention

•

The sequelae of prior limitations upon movement cycles

•

Intentional therapeutic adhesions.

Risks and extent of adhesions further depend on factors such as: type of incision, number of previous laparotomies, damaged visceral or parietal peritoneum and intra-operative complications at initial laparotomy (Van Goor 2007).

Treatment strategies for this group of patients may be divided into treatment of:

•

Abdominal wall scarring

•

Peritoneal and/or visceral adhesions.

Abdominal wall

The goal of scar work is to restore tissue elasticity. Under guidance of the patient’s surgeon, early scar work could be undertaken, aiming to:

•

Stimulate lymphatic absorption. In order to resolve local swelling and induration, manual lymphatic drainage techniques could be used, directing fluids towards the closest lymph nodes.

•

Hasten the release and absorption of buried sutures.

•

Maintain freedom of tissue glide between dermis and underlying tissue layers. As the wound edges may still have no strength to withstand shearing forces in the early phases, tissue engagement and forces should only be applied from healthy tissue towards the scar:

Use gentle circles or ‘J’ strokes at a touch grading of not more than 3

Use gentle circles or ‘J’ strokes at a touch grading of not more than 3

Use gentle stretching techniques along the direction of the scar (longitudinal)

Use gentle stretching techniques along the direction of the scar (longitudinal)

Use only enough force to engage the elastic tissue barrier.

Use only enough force to engage the elastic tissue barrier.

As healing progresses through the remodeling phase towards full maturity, the wound develops strength to withstand tissue loading and progressively more shearing forces perpendicular to the scar. Aims now move towards:

•

Restoring normal tissue barriers:

Stretch vertically above and below the scar. Start stretching tissue along and perpendicular to the scar.

Stretch vertically above and below the scar. Start stretching tissue along and perpendicular to the scar.

Use wringing ‘S’ bends, ‘J’ strokes, firm circles and scar lifting techniques. Engage the tissue barrier and move through the elastic barrier towards the anatomical barrier. Grading of touch can progressively be increased safely towards a grading of 6.

Use wringing ‘S’ bends, ‘J’ strokes, firm circles and scar lifting techniques. Engage the tissue barrier and move through the elastic barrier towards the anatomical barrier. Grading of touch can progressively be increased safely towards a grading of 6.

Take the scar between your fingers and gently lift, stretch, and vibrate.

Take the scar between your fingers and gently lift, stretch, and vibrate.

•

Restoring tissue gliding between deeper fascial and muscle layers progressively working from superficial to deep.

Do not skip layers

.

Using massage, myofascial or combined massage or manual techniques, progressively increase loading, shearing, amplitude and time until full anatomical barriers in all layers have been restored to as close to pre-surgery levels as possible.

Using massage, myofascial or combined massage or manual techniques, progressively increase loading, shearing, amplitude and time until full anatomical barriers in all layers have been restored to as close to pre-surgery levels as possible.

Finish treatment with light effleurage of the area, routing fluids towards lymphatic drainage pathways.

Peritoneal and visceral adhesions

Adhesions develop rapidly after damage to the peritoneum during surgery, infection, trauma or irradiation. They are difficult to detect and evaluate objectively, as they may form in areas not directly linked to the original surgical incision or may develop between structures not accessible to the palpating hand.

The manual evaluation of visceral adhesions depends heavily on the palpation skills of the therapist and a sound knowledge of the visceral anatomy and its variations. Only superficial adhesions between the abdominal wall, parietal peritoneum and immediate underlying viscera may be palpable. The only investigation to date which has shown promise in identifying deep adhesions is the use of cine-MRI (Van Goor 2007).

The following further complicates the interpretation of palpation findings:

•

Pain associated with the adhesion may manifest itself in another location up to 35% of the time

•

Dense, thick adhesions (possibly palpable) are associated with the least intense pain

•

Movable filmy adhesions (mostly non-palpable) are associated with the most intense pain (Van Goor 2007).

Evaluation and treatment principles follow the same guidelines when testing and engaging the internal tissue barrier. These barriers are, however, very subtle as the visceral environment is highly mobile without bony or muscular support. The effectiveness of treatment does not necessarily lie in the selection of a technique, but in the mobilization of the abdominal cavity as a unit.

•

For dense and thick adhesions, engaging and moving the tissue barrier would be the treatment approach. These adhesions are tough and do not respond well to manual techniques alone.

•

Movable and filmy adhesions do not have a palpable tissue barrier, and a generalized mobilization of the abdominal environment may be enough to disconnect mobile organs from the peritoneum.

Cautions

Therapists must use their training and best judgment when deciding whether or not to proceed with scar massage. While treatment is most effective when a scar is still in its immature phase, it is also a wise time to seek physician permission. It is always good practice to monitor the response of scar tissue to determine the appropriateness and effectiveness of massage intervention. Warning signs of potential scar problems include limited range of motion, new onset of joint restrictions, banding of scar tissue with movement, or blanching with stretching of the scar tissue.

A few additional cautions for immature scars include:

•

Take extreme care with radiated tissues, as the skin is delicate and can break easily

•

Aside from friction massage, do not continue if your actions cause pain or increase tissue redness

•

Never perform massage on any open lesions.

In many cases the problem may be irreversible with scars becoming so fixed and strong that only surgery will release the adhesion. In established fixed scars, where no tissue gliding is possible by manual means, treatment is aimed at creating more soft tissue space and flexibility in the surrounding tissue. In many cases adhesive scarring may affect quality of life adversely; however, open, positive discussion with adequate explanation and intervention may vastly diminish the patient’s anxiety, suffering and disability, making scar work a rewarding field in manual therapy.

References

Andrade C-K, Clifford P 2008 Outcome-based massage, from evidence to practice, 2nd edn. Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia

ASRM Committee 2013 Pathogenesis, consequences, and control of peritoneal adhesions in gynecologic surgery: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 99:1550–1555

Atiyeh BS 2007 Nonsurgical management of hypertrophic scars: evidence-based therapies, standard practices, and emerging methods. Aesth Plast Surg 31:468–492

Bouffard NA et al 2008 Tissue stretch decreases soluble TGF-β and type-1 procollagen in mouse subcutaneous connective tissue: evidence from ex vivo and in vivo models. J Cell Physiol 214:389–395

Chaitow L, DeLany J 2008 Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques, vol 1. The upper body, 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, Edinburgh

Curties D 1999 Breast massage. Curties-Overzet Publications, Toronto

Ellis H 2007 Postoperative intra-abdominal adhesions: a personal view. Colorectal Dis 9(Suppl 2):3–8

Ergul E, Korukluoglu B 2008 Peritoneal adhesions: facing the enemy. Int J Surg 6:253–260

Fourie WJ, Robb K 2009 Physiotherapy management of axillary web syndrome following breast cancer treatment: discussing the use of soft tissue techniques. Physiotherapy 95:314–320

Guimberteau J-C, Armstrong C 2015 Architecture of human living fascia. The extracellular matrix and cells revealed through endoscopy. Handspring Publishing, Edinburgh

Hedley G 2010 Notes on visceral adhesions as fascial pathology. J Bodyw Mov Ther 14:255–261

Lederman E 1997 Fundamentals of manual therapy. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Lee T S et al 2009 Prognosis of the upper limb following surgery and radiation for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 110: 19–37

Lewit K, Olsanska S 2004 Clinical importance of active scars: abnormal scars as a cause of myofascial pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 27: 399–402

Moortgat P et al 2016 The physical and physiological effects of vacuum massage on the different skin layers: a current status of the literature. Burns Trauma 4:34

Myers BA 2012 Wound management: principles and practice, 3rd edn. Pearson Education, New Jersey

Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Choi CH 2000 Arthroscopic management of degenerative joint disease. In: Grifka J, Ogilvie-Harris DJ (ed) Osteoarthritis: fundamentals and strategies for joint-preserving strategies. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Piedade SR, Pinaroli A, Servien E, Neyret P 2009 Is previous knee arthroscopy related to worse results in primary total knee arthroplasty? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17:328–333

Roques C 2002 Massage applied to scars. Wound Repair Regen 10(2): 126–128

Shin TM, Bordeaux JS 2011 The role of massage in scar management: a literature review. Dermatol Surg 38:414–423

Smith N K, Ryan C 2016 Traumatic scar tissue management. Massage therapy principles, practice and protocols. Handspring Publishing, Edinburgh

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, 22nd edn. 1972 Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Van Goor H 2007 Consequences and complications of peritoneal adhesions. Colorectal Dis 9 (Suppl. 2):25–34

Villeco JP 2012 Edema: a silent but important factor. J Hand Ther 25:153–162

The

parietal peritoneum

as the outer lining of the abdominal cavity

The

parietal peritoneum

as the outer lining of the abdominal cavity

The

parietal peritoneum

as the outer lining of the abdominal cavity

The

parietal peritoneum

as the outer lining of the abdominal cavity

Visceral peritoneum

covering the viscera and organs contained therein.

Visceral peritoneum

covering the viscera and organs contained therein.

Take up all the tissue slack.

Take up all the tissue slack.

Apply a gentle stretch along the length of the scar.

Apply a gentle stretch along the length of the scar.

Hold, wait for release and stretch again.

Hold, wait for release and stretch again.

Change hand position and repeat the stretch perpendicular to the original stretch.

Change hand position and repeat the stretch perpendicular to the original stretch.

Repeat the stretch sequence diagonal to the previous position.

Repeat the stretch sequence diagonal to the previous position.

Continue to stretch across the scar in a radiating pattern until no further stretch is possible.

Continue to stretch across the scar in a radiating pattern until no further stretch is possible.

Rest the fingers on the part to be treated (next to the scar). The heel of the hand may rest on the body for better control (

Fig. 18.2A & C

).

Rest the fingers on the part to be treated (next to the scar). The heel of the hand may rest on the body for better control (

Fig. 18.2A & C

).

Starting at the 6 o’clock position, push the skin clockwise in a circle with the middle three fingers.

Starting at the 6 o’clock position, push the skin clockwise in a circle with the middle three fingers.

Slowly move the skin towards the scar to engage and shear the tissue barrier in a circular movement with even pressure and speed.

Slowly move the skin towards the scar to engage and shear the tissue barrier in a circular movement with even pressure and speed.

Change hand position, repeat the circle and release.

Change hand position, repeat the circle and release.

Treat the full length of the scar and repeat several times in a session if needed.

Treat the full length of the scar and repeat several times in a session if needed.

Direct the stroke perpendicular towards the scar from about an inch (2.5 cm) away.

Direct the stroke perpendicular towards the scar from about an inch (2.5 cm) away.

Movement is slow, firm and deliberate into the tissue barrier.

Movement is slow, firm and deliberate into the tissue barrier.

When the barrier is engaged, the fingers shear away towards the left or right and the tissue is allowed to return to its non-stretched position.

When the barrier is engaged, the fingers shear away towards the left or right and the tissue is allowed to return to its non-stretched position.

Repeat until the tissue barrier has moved, or discomfort subsides.

Repeat until the tissue barrier has moved, or discomfort subsides.

Grip an area of the scar gently, but firmly.

Grip an area of the scar gently, but firmly.

Apply a vertical stretch perpendicularly off the surface of the body.

Apply a vertical stretch perpendicularly off the surface of the body.

Hold, wait for a release and increase the stretch.

Hold, wait for a release and increase the stretch.

Repeat the lift sequence from different angles until no further stretch is available.

Repeat the lift sequence from different angles until no further stretch is available.

Using as broad a contact surface as possible, grasp the skin and superficial fascia between thumb and fingertips.

Using as broad a contact surface as possible, grasp the skin and superficial fascia between thumb and fingertips.

Lift the tissue and, while maintaining a stretch on the tissue, roll the superficial tissue along the surface in a slow wave.

Lift the tissue and, while maintaining a stretch on the tissue, roll the superficial tissue along the surface in a slow wave.

Glide the thumb or fingers along the tissue as you simultaneously gather and release tissue while maintaining the grasping and lifting motion.

Glide the thumb or fingers along the tissue as you simultaneously gather and release tissue while maintaining the grasping and lifting motion.

Use gentle circles or ‘J’ strokes at a touch grading of not more than 3

Use gentle circles or ‘J’ strokes at a touch grading of not more than 3

Use gentle stretching techniques along the direction of the scar (longitudinal)

Use gentle stretching techniques along the direction of the scar (longitudinal)

Use only enough force to engage the elastic tissue barrier.

Use only enough force to engage the elastic tissue barrier.

Stretch vertically above and below the scar. Start stretching tissue along and perpendicular to the scar.

Stretch vertically above and below the scar. Start stretching tissue along and perpendicular to the scar.

Use wringing ‘S’ bends, ‘J’ strokes, firm circles and scar lifting techniques. Engage the tissue barrier and move through the elastic barrier towards the anatomical barrier. Grading of touch can progressively be increased safely towards a grading of 6.

Use wringing ‘S’ bends, ‘J’ strokes, firm circles and scar lifting techniques. Engage the tissue barrier and move through the elastic barrier towards the anatomical barrier. Grading of touch can progressively be increased safely towards a grading of 6.

Take the scar between your fingers and gently lift, stretch, and vibrate.

Take the scar between your fingers and gently lift, stretch, and vibrate.

Using massage, myofascial or combined massage or manual techniques, progressively increase loading, shearing, amplitude and time until full anatomical barriers in all layers have been restored to as close to pre-surgery levels as possible.

Using massage, myofascial or combined massage or manual techniques, progressively increase loading, shearing, amplitude and time until full anatomical barriers in all layers have been restored to as close to pre-surgery levels as possible.