Chapter 7

Effective Change Model

As a consumer, I hate call centers that force me to talk to robots. I find it frustrating to have to work through a long menu of options for support with robots, especially when their voice recognition is poor. (Or is it possible that I have a blind tendency to discriminate against robots, for which I will pay dearly when they become our overlords in the future? I’m kidding!) In any case, I was genuinely surprised in 2015 when our new NGS team found that AI-based call center support was a major disruptive focus among start-ups. As it happened, we were looking for 10X improvement solutions for our Global Consumer Relations service, which provides phone, email, and social media support to all consumers of P&G products worldwide. We established an NGS project and ran through a quick cycle of hypothesis testing with the technologies in four weeks that demonstrated that it was a very viable 10X idea.

Two months later, we killed this effort. The technology was indeed viable, and the service line leaders in GBS were clearly sponsoring the effort, but the project was not making satisfactory progress within their core operating organization. The kill decision was based on our NGS portfolio approach of 10-5-4-1, where for every ten experiments (projects), we would stop five, expect four to deliver 2X results, and one would become a huge 10X hit. Over the next three years we would similarly kill dozens of potentially viable projects. Ninety percent of the time the issue was not technology viability but a lack of sufficient progress within the receiving operating organization. In all these cases, our goal was to stop the effort as early as possible, to recognize the “kill decision” publicly, and to move on.

Two years later, the conditions within the Global Consumer Relations organization had changed, and so the old project was revived. It is currently turning out to be one of the most successful efforts in the current portfolio.

Change Management Is a Major Failure Point for Stage 3 Transformation

Change management is tough at any stage, but it is the most likely cause of failure at Stage 3 even among strong, well-intentioned enterprises. Even though the transformation strategy has been declared, the change never seems to take root in the core organization.

Work backward from change acceptance strategies toward change creation, not the other way around.

Past experience with disruptive innovation at GBS had led us to a different way of thinking about effective change management in NGS. We decided that our operating model ought to work backward from change acceptance toward change (product) creation, as opposed to the traditional approach of creating the product first and then figuring out how to drive acceptance along the way. Here’s one simple example of how this insight was used. In deciding on whether to locate the NGS team in Silicon Valley or at P&G HQ in Cincinnati, I chose the latter. I determined it would be in the best interests of driving change into the core operations for the team to be based there.

In this chapter, I explore how choosing an effective change model can be done in a disciplined manner. In essence, this consists of three parts:

![]() Understand your change situation transformation (e.g., burning platform, proactive change, etc.).

Understand your change situation transformation (e.g., burning platform, proactive change, etc.).

![]() Choose the appropriate change management model for it (e.g., organic change, inorganic change, etc.).

Choose the appropriate change management model for it (e.g., organic change, inorganic change, etc.).

![]() Create plans to motivate those affected by the change.

Create plans to motivate those affected by the change.

To illustrate how this works, let’s investigate a couple of case studies for insights before using them for our change-model discipline. Let’s go back in time to the case study of the Year 2000 (Y2K) global effort. Our younger readers may have only a fleeting knowledge of this, but the Y2K problem was a very big deal in the 1990s. At a time when IT was not the consumer phenomenon that it is today, it caused a barely understood topic to hit the front pages for a frightening reason—this problem could cause all types of real-world disasters to happen.

Why the Global Y2K Fix Effort Succeeded

The Y2K computer glitch story may be the biggest example of successful global collaboration on an IT issue in our lifetime. The issue boiled down to twentieth-century programming practices where the storage of a number representing a year (e.g., 1998) was often done in two digits (e.g., 98). The program treated any computation that involved a year—say computing the number representing “next year”—by simple mathematical action against that number (e.g., 98 + 1 = 99). That worked perfectly for most of the twentieth century. The problem arose when the computations gave you a three-digit result (e.g., 99 + 1 = 100). Most programs failed when they tried to store a three-digit result in a two-digit number.

There was also a smaller secondary issue with leap years, where computer programmers incorrectly coded leap years in the Gregorian calendar. They simply programmed any year divisible by 100 as not being a leap year, forgetting that the exception was for years divisible by 400. Thus, the year 2000 should have been programmed as a leap year.

The problem was easy to explain, but the fix was easier said than done. There was no easy way to find out which specific programs were incorrectly coded with two-digit years as opposed to the correct four-digit years. Worse still, many of the original programs would have been modified locally, with little to no documentation of the changes. You’d have to go through each and every program and fix it.

In the end the new millennium dawned and passed without incident. Somehow in the last remaining years of the twentieth century, governments and business leaders took charge and delivered their individual fixes. Keep in mind that these were the days when IT was not fully understood by most organization leaders and stakeholders. Even so, without fully understanding the cause of the problem, most leaders were clear about what success looked like.

The Y2K fix is a good example of working backward from change demand toward change supply. Billions of people across the world wanted this to happen. Every organization knew exactly what it had to do, regardless of what others chose to do. The effort is also a good example of the sociological phenomena underpinning crisis-like change, i.e., there are hidden extra reserves that kick in when facing an existential threat.

To be clear, the goal isn’t to frame a digital transformation in crisis terms. Such extra reserves can also be called upon when there’s a very exciting opportunity as well. The story of how P&G’s Global Business Services tapped into those reserves to help with the humungous effort needed to integrate Gillette into P&G in 2005 brings this point to life. That story is not related to the main NGS example, but it is one of the best examples of how to create the conditions for successful change management that I have come across.

P&G’s Integration of Gillette

In January 2005, Procter & Gamble announced that it would acquire Gillette for $57 billion. This was P&G’s largest acquisition by far. The company that was a household name globally—with products such as Tide/Ariel, Pantene, Pampers, Bounty, Oil of Olay, and Vicks, among others— would add more iconic brands such as Gillette, Duracell, and Braun.

Filippo Passerini, P&G’s visionary president of Global Business Services and IT, looked at this as an opportunity. He thought he could run the combined IT-related services of both companies without increasing the head count or spending above P&G’s current numbers. Further, since P&G wanted to aim at exceeding Wall Street expectations about the acquisition, Passerini proposed to integrate all the IT systems within eighteen months.

Ultimately, Passerini did just that. P&G exceeded not just cost synergy targets but also delivered them ahead of the committed schedule. What went into delivering these outstanding results is very instructive with regards to deliberately creating environments where change is accepted.

To create a common and tangible sense of purpose for the entire company, Passerini computed that each day’s delay on integration would mean a $3 million loss in cost synergies. This ended up being the capstone piece on change management. It drove a real sense of urgency across the enterprise.

Second, although Passerini took a personal risk to commit to the goals up front and execute the change with highly visible and structured delivery, this created momentum that made it somewhat difficult for the usual change-resistance inertia to take root.

Each wave of systems change was executed with excellence. Any problems that arose during systems changeovers were swiftly dealt with by people manning “Hypercare” centers who ensured that there was no business interruption. What resulted was an industry success story on how to integrate the systems of an acquisition swiftly and successfully.

Having been involved in both the Y2K effort at P&G as well as the integration of Gillette’s systems as P&G’s CIO, it was fascinating for me to compare the change management models across the two. Despite having very different drivers of change, they both created equally effective change-acceptance motivations. I describe in the following sections how it is possible for leaders to read the prevailing landscape using a simple change framework and create strong motivations for change in the organization.

The Discipline of Understanding the Change Conditions

When it comes to understanding why the change models worked, the first story of the Y2K fixes is easier to understand than the second one of the integration of Gillette systems. After all, the world was facing a disaster scenario. And yet, the Gillette systems integration project successfully created an environment that was not too dissimilar to the global crisis Y2K project. How do change leaders tap into the same organization energy reserves in noncrisis situations?

It is important to sense the right change situation (i.e., change urgency vs. acceptance) and, if necessary, even create specific types of change situations through strong leadership, communication, and discipline.

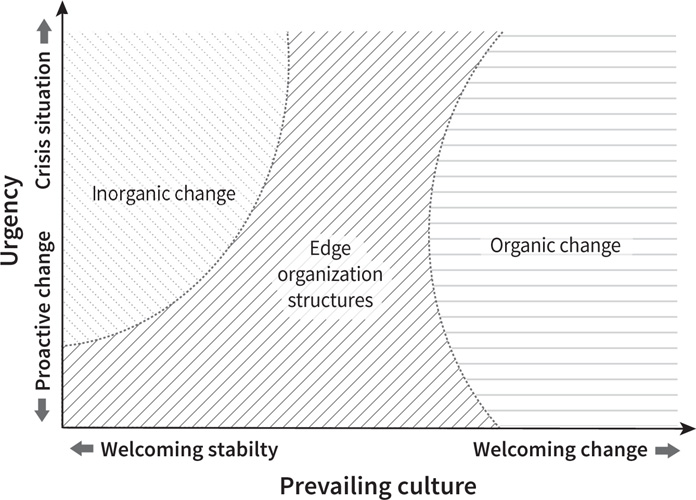

Strong change leaders create these conditions intuitively. But there is some science behind this. It all hinges on understanding the landscape and applying the right change management models. Strong change leaders understand how much support they have not just at the sponsor level but also with those affected by the change. They understand the prevailing culture of the organization and the type of communication that will be most productive. I use a simple model in figure 16 that maps the urgency of change to the prevailing change acceptance culture, to illustrate this effect. Crisis situations are easier to diagnose and therefore make it easier to choose the right change model. The perceived urgency of the situation typically overrides most other considerations, including change culture. The Y2K fix crisis fell into this category.

The P&G integration of Gillette was a little trickier. It was not a business crisis, and there were different motivations involved, including balancing stability with change. The successful strategy employed there was to create a cultural effect of “welcoming change” by using the motivation systems of the organization. By putting together a proposal for a common goal to meet and exceed external expectations and combining it with a rigorous organizing and accountability framework for every player (including putting a dollar value to delays like Passerini did), a common purpose and sense of urgency was created. The point is that it is important to sense the right change situation and, if necessary, even create specific types of change situations (e.g., urgent change, exciting future change, etc.) through strong leadership, communication, and discipline.

Figure 16 Change situations

The Discipline of Using the Correct Change Model

Once the change management situation has been identified per figure 16, the next step is to decide whether to drive change organically, via edge organization structures, or inorganically, all of which are defined below. An edge organization is a structure that distributes knowledge and power to the “edges” of an organization, enabling it freedom to innovate.27 If time, capability, and a relatively straightforward digital change per figure 16 are available, then it can usually be handled via organic change. Otherwise you’re looking at edge organization structures or inorganic change.

Organic Change

Organic change involves internally setting digital transformation goals, building or buying the right capabilities, educating the organization, and setting the right project execution structures. GE’s execution of its well-known digital strategy of creating a separate division called GE Digital is an example of organic change. Though its strategy to become a data company has failed at the moment, that is more related to two other disciplines (iterative execution and strategy sufficiency).

An approach to expediting organic change is to implement the technologies, behaviors, and processes of an exponential organization (ExO). An ExO essentially uses new organizational techniques that leverage exponential technologies. Inherent in these techniques is the use of nimble, open-team setups and rapid decision making, combined with exponential tools such as algorithms or crowdsourcing.

Edge Organization Structures

If there is little time available and the prevailing organization culture is resistant (even if not closed) to change, then organic change won’t work. In such cases, edge organizations that involve creating separate disruptive innovation structures are the preferred approach. Edge organizations are a relatively new construct with great promise for driving change. These organizations consist of highly extended and unconstrained teams that are agile in creating and adapting to change. The charge to apply this concept to large enterprises has been led by John Hagel III, one of the best enterprise change experts I have come across. The legendary example of edge organizations is the original Skunk Works. The Skunk Works group was set up at Lockheed Martin in 1943 as an independent structure that was allowed great freedom from normal processes and rules so that they could develop the XP-80 jet fighter in record time. This type of edge organization works only if it is given full freedom to operate differently than the core.

Inorganic Change

If existing capabilities, time, and internal resistance to change are all a challenge, then your best bet may be to look for an acquisition or partnership with an external entity. Walmart’s acquisition of Jet.com is a good example. Inorganic change comes with its own risk since a majority of acquisition-related change fails. However, by giving the acquired entity a strong mandate and change-management support, this approach can jump-start new capabilities quickly.

For additional reading, Salim Ismail’s book Exponential Organizations28 has an excellent chapter on this topic: “ExOs for Large Organizations.” It provides great detail on four strategic options that mirror our spectrum of organic change, disruptive structures, and inorganic change.

Choosing the most appropriate change model will get the digital transformation off to a strong start. However, to maintain ongoing momentum, there’s usually an immune system to be overcome.

Follow the discipline of choosing the best change model (i.e., organic change, edge organization structures, or inorganic change) for your situation.

The Science of Immune System Management

A corporate immune system is not necessarily a bad thing. Like its counterpart in the human body, it plays a vital role. In our bodies, the immune system protects us from disease and keeps us healthy. It is true that immune system disorders can be problematic (i.e., an immune system deficiency leaves the body susceptible to constant infections, while an overactive immune system will fight healthy tissues). However, on balance, a healthy immune system is desirable.

If that’s true, then why do so many change leaders blame the corporate immune system when things go south? Shouldn’t disciplined change leaders understand the strength of the immune system within their own organizations and prepare for appropriate handling?

For each of the twenty-five experiments (projects) that the NGS team executed during my three years, there was always a proactive immune system conversation and plan. It made a huge difference versus historical trends on disruptive change acceptance.

There are three key principles to bear in mind:

![]() The immune system is not necessarily a bad thing. Anticipate and prepare for immune system responses.

The immune system is not necessarily a bad thing. Anticipate and prepare for immune system responses.

![]() Immune system responses can originate at all levels in the organization, but the toughest ones occur at middle management.

Immune system responses can originate at all levels in the organization, but the toughest ones occur at middle management.

![]() The bigger the change, the harder the immune system response (i.e., digital transformation will be tough).

The bigger the change, the harder the immune system response (i.e., digital transformation will be tough).

Having covered the first item, let’s zero in on the issue of middle management reaction. In most organizations, it is easy to get senior executive leadership excited about change. Similarly, the younger generation gets quickly on board. It is the middle management layer that’s on the critical path and has the potential to slow down or even block change. The term “frozen middle” has been associated with this phenomenon. This concept was published in a Harvard Business Review article in 2005 by Jonathan Bynes.29 Bynes’s point was that the most important thing a CEO could do to boost company performance was to build the capabilities of middle management.

For corporate immune system disorders at the middle management level, the term “frozen middle” is accurate, but it comes with the risk of being pejorative for seeming to blame middle management for recalcitrance and inertia. In reality, the responsibility to bring middle management along on the journey resides with the change leaders and their sponsors. Consider this—the so-called frozen middle protects the enterprise from unnecessary distractions and change, just like the human immune system protects the body from harmful change. Middle managers are rewarded mostly for running stable operations. Is it fair to criticize them as a whole for doing what their reward system dictates? We must separate immune system disorders from normal immune system responses.

Pay special attention to creating the reward systems for middle managers to successfully enable the change.

At NGS, we paid special attention to identifying, by name, the middle management leader for each affected project. A lot of effort was put in up front to enroll them, including working with their leaders to tweak their reward systems in order to encourage leadership on the change project. In the few cases that were likely to fall in the category of an immune system disorder, the sponsor was roped in to develop appropriate motivation systems. Worst case, if that didn’t work, was that the project was quickly killed. That worked well because of the portfolio effect of having several other projects available in the pipeline.

Why the Frozen Middle Is Especially Important in Digital Transformations

Though the concept of a frozen middle is applicable broadly, overcoming it has never been as critical as it is with digital disruption. The amount of change necessitated by a true Stage 5 transformation is massive. This isn’t just a technology or product or process change but also an organizational culture change. The middle management will need to lead the rest of the organization in learning new capabilities (i.e., digital) as well as new ways of working in the digital era, including encouraging agility, taking risk, and re-creating entire new business models and internal processes. Retraining middle management on digital possibilities is not sufficient. Entirely new reward systems and organizational processes will be called for.

Chapter Summary

![]() Although every airplane takeoff plans for headwinds, most digital transformations treat it as an afterthought. The discipline of addressing the choices of effective change models is designed to address this.

Although every airplane takeoff plans for headwinds, most digital transformations treat it as an afterthought. The discipline of addressing the choices of effective change models is designed to address this.

![]() To understand how successful change management works, this chapter included a couple of success stories—the global Y2K fix and the highly successful systems integration of Gillette into Procter & Gamble.

To understand how successful change management works, this chapter included a couple of success stories—the global Y2K fix and the highly successful systems integration of Gillette into Procter & Gamble.

![]() There are disciplined steps involved in selecting the best change models. The first is a clear understanding of the organization’s change conditions.

There are disciplined steps involved in selecting the best change models. The first is a clear understanding of the organization’s change conditions.

![]() Based on the change situation, three types of change management strategies are available for digital transformation:

Based on the change situation, three types of change management strategies are available for digital transformation:

![]() Organic change

Organic change

![]() Edge organization structures

Edge organization structures

![]() Inorganic change

Inorganic change

![]() Finally, the discipline of addressing the reward systems of the corporate frozen middle proactively builds capabilities and culture at the middle management layer to accept and thrive in digital transformation.

Finally, the discipline of addressing the reward systems of the corporate frozen middle proactively builds capabilities and culture at the middle management layer to accept and thrive in digital transformation.

Your Disciplines Checklist

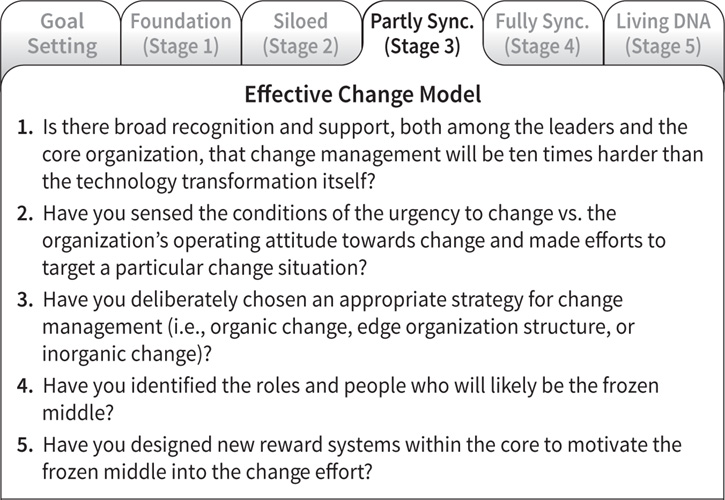

Evaluate your digital transformation against the questions in figure 17 to follow a disciplined approach to each step in Digital Transformation 5.0.

Figure 17 Your disciplines checklist for effective change model