CHAPTER TEN

Diet & Health

For non-commercial setups, there are no hard-and-fast rules stating precisely what each chicken’s daily ration of feed should be. It will vary depending on the time of year, the weather, the temperature, the rate of lay, the bird’s age and weight, the amount of effort it expends during its day, and the nutritional value of the feed it is receiving. This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try to establish an average range of daily feed consumption for your stock. This will enable you to budget correctly and also spot any issues with feed intake that could signal that a flock member may be ill, broody, or otherwise not its usual self.

Most keepers feed their flock with a commercially manufactured feed, as this ensures that they receive the correct balance of the nutrients they require (see here). This feed usually comes in the form of mash or compound pellets. Nowadays, “mash” is the term used to describe a commercially manufactured powdery feed that needs mixing with water before giving to the chickens. The keeper needs to mix up the mash each day; once mixed with water, it will go stale quickly. Pellets are simply the same feed but pressed into a pellet shape, making them easier to manage and removing the need to mix up feed on a daily basis. They also last longer than mash mix once out of the sack and hence are more economically viable for the small-flock owner.

Getting the balance right in a hen feed is essential if the hens are to perform well.

While formulated commercial diets provide all the nutrients your hens need, a few supplements will further improve their health and well-being.

OYSTER SHELL

Oyster shell is often given to laying hens as a free-choice supplement to enhance eggshell quality, especially as they get older. An additional benefit of providing oyster shell over simply increasing the limestone content of the feed is that the large size of the particles means they dissolve slowly in the gut, providing a slow release of the minerals calcium and phosphorus. Interestingly, hens that require more calcium in their diet will sense this need and seek out and consume oyster shell. It should be noted that the slow release of these minerals makes oyster shell an unsuitable supplement for birds exhibiting a lack of calcium; instead, these birds should be given a fast-acting liquid calcium supplement.

SCRATCH FEEDS

Scratch feed is generally a mixture of any number of cereal grains—often cracked corn and wheat—and is fed by scattering it on the ground so that the hens can scratch around for it as a treat and as exercise. Scratching for food is a leftover from the natural behavior of the chicken’s jungle-fowl ancestors, which searched through the debris on the jungle floor for insects and seeds. Scratch should not be considered a feed but should be used only as a treat. Consumption of large amounts of scratch can put a chicken’s daily intake severely out of balance and over the long run reduce its productivity.

It is always useful to provide the flock with a scratch feed an hour or two before the birds go in to roost. This not only provides them with a full crop before roosting (particularly useful during the colder winter nights), but provides activity and stimulus, encourages flock cohesion, and keeps their toenails down.

The other advantage of getting your flock used to a daily scratch feed is that the birds will respond to you bringing it to them no matter what the time of day. If the scratch feed is provided within the run, you can attract free-ranging birds back to a fixed area at any point of the day. Alternatively, providing a small quantity in the coop will bring them indoors. Both scenarios are particularly helpful if you need to catch and handle the birds during the day or if you need to confine them earlier than their normal roost time.

GRIT

Grit is required by chickens to aid in digestion. When chickens eat, they swallow everything whole, since they don’t have teeth for grinding. Foraging chicken often consume whole grains or insects with hard exoskeletons that require grinding to be digested. When the grit is swallowed, it is lodged in the gizzard, the muscular stomach of birds, where muscle contractions grind the feed against the hard particles.

Grit comes in a variety of sizes—it is important that the size of the grit provided is appropriate for the age and breed of the chicken. Some grits contain additional trace minerals to supplement the diet. Grits should be freely available to the birds and not mixed with feed, as chickens will seek it out as and when they need it.

VITAMIN & MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS

Essential vitamins are required for the health and growth of chickens but they cannot be synthesized by the birds themselves so need to be included within their food (studies have shown that chickens require all vitamins apart from vitamin C). Free-ranging birds will forage for much of their feed and, as such, will pick up a lot of the essential vitamins they require from their varied diet. Confined birds, however, will be reliant upon the keeper and the quality of the feed provided. Most commercial feeds contain sufficient daily allowances of the vitamins chickens need, but the vitamin content will begin to degrade after the “best before” date. If your chickens aren’t free-range, then it is important to ensure they have sufficient vitamins in their diet. One way of doing this is to give them multivitamins.

There are many varieties of multivitamins for chickens on the market, from pleasant-smelling powders that can be mixed in with the feed to liquid supplements that can be added to the drinking water. Different keepers have different preferences regarding which to use, and these are as much based on the method of application as on the actual ingredients. However, most keepers agree that these natural vitamins and minerals give the birds a boost during their molt, in the spring and winter, at times of stress, and in particular before exhibiting.

There has been a resurgence in allowing chickens to forage on pasture. As a feedstuff for chickens, pasture itself is poor, as the birds can’t digest cellulose, the primary component of grasses. However, they do enjoy picking out the insects that pasture attracts and the seeds the grasses produce at certain times of the year. As the grass begins to grow in the early spring, the insect population provides an excellent protein-rich food source for the foraging birds. However, this resource is limited over time as the insect population declines. In the summer, grasses that are allowed to mature produce seeds that can provide some nutrition for chickens. As late summer turns to fall, the seeds are gone and the insect population declines to the point where it is virtually nonexistent. Cold, wet, and snowy winter conditions eliminate pasture grasses as a feed for chickens. Then it’s back to spring for another cycle.

Therefore, on an annual basis, little feed value is obtained by allowing chickens to forage on pasture. Rotating the birds on paddocks, keeping the numbers low enough so that the insect population is not reduced too quickly, and planting pasture grasses that attract insects and increase seed production will enhance their value as a feed supplement.

Allowing access to fresh pasture can mean access to various seeds and insects for the hens.

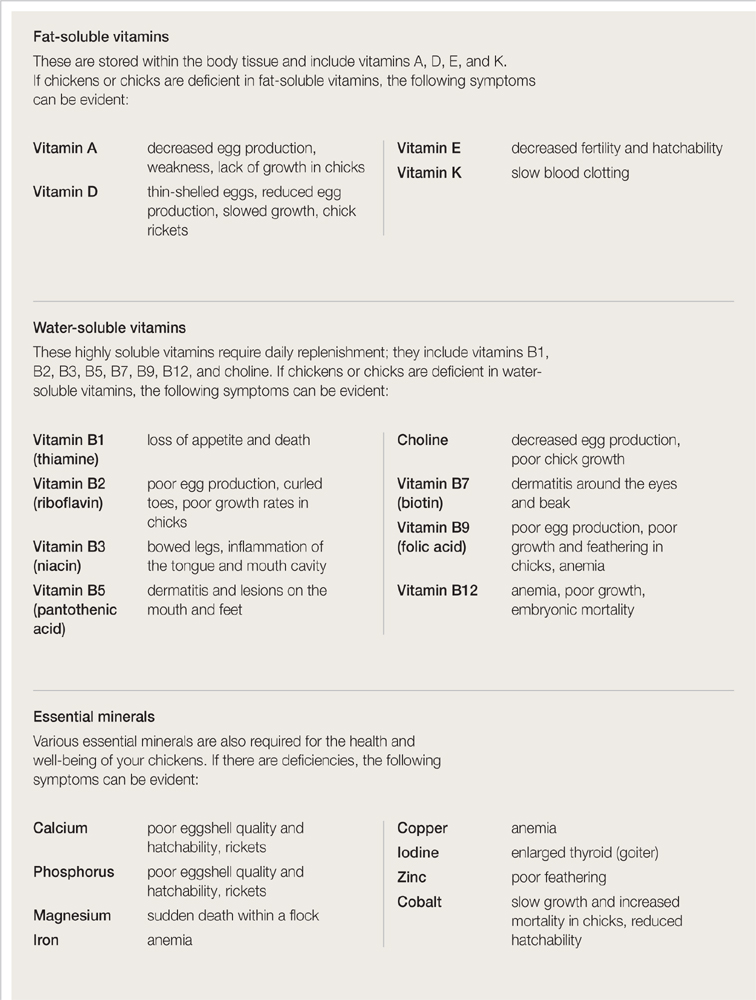

Vitamin & Mineral Deficiencies

Take 9.5 pints (4.55 liters) of water and add one tablespoon of sugar (sucrose), one teaspoon of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), one teaspoon of salt (sodium chloride), and half a teaspoon of salt substitute (potassium chloride). Mix until dissolved and then offer to the chicken in place of normal drinking water for five hours before replacing with normal drinking water. Repeat this process for five to seven days, and then reinstate normal drinking water altogether. By this point, the chicken should be showing a marked recovery.

If a chicken is suffering dehydration, for example due to an extended bout of diarrhea, or is recovering from a heavy worm infestation, then essential minerals can be leached from the body. The health and well-being of a chicken can be dependent upon these minerals, so it is important that they are replaced in order to enable a rapid recovery. This can be achieved by providing the chicken with an electrolyte mix.

Pre-mixed electrolyte powders and solutions are available off the shelf, but it is possible to mix your own from ingredients found in the home (see box). This is especially useful if the feed store is some distance away, or the need arises outside of normal business hours.

APPLE CIDER VINEGAR (ACV)

This supplement can be added to the chickens’ drinking water, but because it is acidic, note that it should not be used in metal waterers, or they will corrode. ACV is used as a general health supplement for other animals and for humans, but be sure to use the unrefined product for livestock, which can be purchased from agricultural merchants, as opposed to the ACV available for people.

As a dietary supplement, ACV can help control intestinal pests, such as worms, by marginally changing the pH of the digestive system. The dosage rate is 5 teaspoons of ACV to 2 pints (1 liter) of drinking water, which should be given to the chickens for a period of 10–14 days. This can be followed by maintenance periods at the same concentration of either two days a week (the weekend, for example), or one week per month.

OREGANO

Oregano is another useful dietary supplement, with antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, and antioxidative properties; it also helps boost the immune system of chickens. Oregano oil extracts can be purchased, but hanging a bunch of fresh oregano in the run not only provides the herbal health benefits but also gives your chickens some greens and entertainment.

GARLIC

The health benefits of garlic are widely known and written about, again not only in humans, but in animals such as horses. Garlic is also very beneficial for chickens and, if not used to excess, doesn’t taint the flavor of eggs.

Garlic can give the chicken’s immune system a boost in much the same way as it does for humans, and there is evidence to suggest it reduces infestations of internal and external parasites, particularly of the blood-sucking variety. It has also been proven to reduce the odor of chicken manure, so, all in all, it is a handy supplement to the diet.

Oregano is also known as wild marjoram. It has purple flowers and olive-green leaves. Its dietary benefits make it a useful addition to your run.

Garlic granules can be purchased at most feed stores, although they are usually in the equine rather than the poultry section. These can be scattered into the chicken feed, and most chickens seem to like the taste, picking it out of the feed when they sense it’s there. There are also products on the market that contain concentrated garlic extract (allicin), which can be used both as a preventative and a treatment for worms and other parasites that affect chickens. These products are usually added to the chickens’ drinking water.

A homemade alternative is to add a clove or two of garlic to your chickens’ waterer. It will gradually become mushy and release its oils into the water for the chickens to ingest. Once the waterer is empty, don’t throw the clove away; hand it to the nearest chicken, which will enthusiastically consume it. Again, the strength of flavor in the clove will have dissipated so as not to taint the eggs of that bird.

COD LIVER OIL

In much the same way that garlic has been known to provide health benefits in animals, so has cod-liver oil. It is rich in vitamins A and D, and is a valuable general aid to feather conditioning, especially during periods of molt. Like garlic, if used in moderation, it will not taint the taste of eggs.

Cod-liver oil is also particularly useful in helping powder-based medications, such as worming powder, stick to the chickens’ feed, ensuring that the medication is consumed and doesn’t simply fall to the bottom of the feeder. Simply measure out the required powder and sufficient feed to ensure that all birds being treated will receive their daily ration, and then mix the two together with two teaspoons of cod-liver oil per 1 lb. (450 g) of feed.

Catching, Carrying, & Crop Reading

Spend enough time around a flock of chickens and it will soon become apparent that there is a significant amount of husbandry by eye that is required. A good stockperson will be able to cast a glance across the animals and spot anything that seems out of line. This is a skill that is particularly worth acquiring when it comes to a flock of chickens, as the birds can disguise ailments that might identify them as being weak or vulnerable to predation.

A hunched or drooped stance, a discolored comb or droppings, poor feather condition, or lack of alertness can all be indicators of illness and should be investigated by catching the hen. The simplest time to do this is when a bird is roosting and is perched. It can easily be lifted off and handled. If you need to catch the bird during the day, try to corral it into a corner.

Once the chicken is in hand, trap its wings against the sides of its body. With a tame bird, this can be done simply with your thumb and little finger as the bird’s undercarriage sits in the palm of your hand. If the bird is not tame and is struggling to escape, hold it with one of the wings to your chest and one hand over the other wing. Your second hand should then be used to hold the legs firmly together (but not too tightly). If the bird continues to struggle, place a cloth over its eyes to help it settle.

CROP READING

Whenever you are holding a chicken, it is always worth checking the bird over for parasites and assessing its overall condition as you did when you purchased your birds (see here). Crop reading is also worthwhile. The crop is the first section of a chicken’s digestive system reached after food has entered the mouth and traveled down the esophagus. It sits beneath the neck of the chicken and toward the front of the breast, and can easily be felt by the keeper when the bird is in the hand.

“Reading” the crop by gently feeling its condition means you can perform a basic health check on the bird. Normally a crop will contain food (unless the bird has yet to eat that day) and will feel like a slightly soft ball when squeezed gently. If the bird has not eaten or is off its food, the crop should feel empty and almost absent. If the crop feels solid and hard, the bird could have an impacted crop, whereas if it feels watery and squishy (and the bird’s breath smells strong), the bird could have sour crop.

Being familiar with these basic crop conditions will help significantly in managing the welfare of individual birds. If you think a member of your flock has an impacted or sour crop, or you are concerned about its condition, refer to the table opposite and overleaf, and contact your vet as soon as possible.

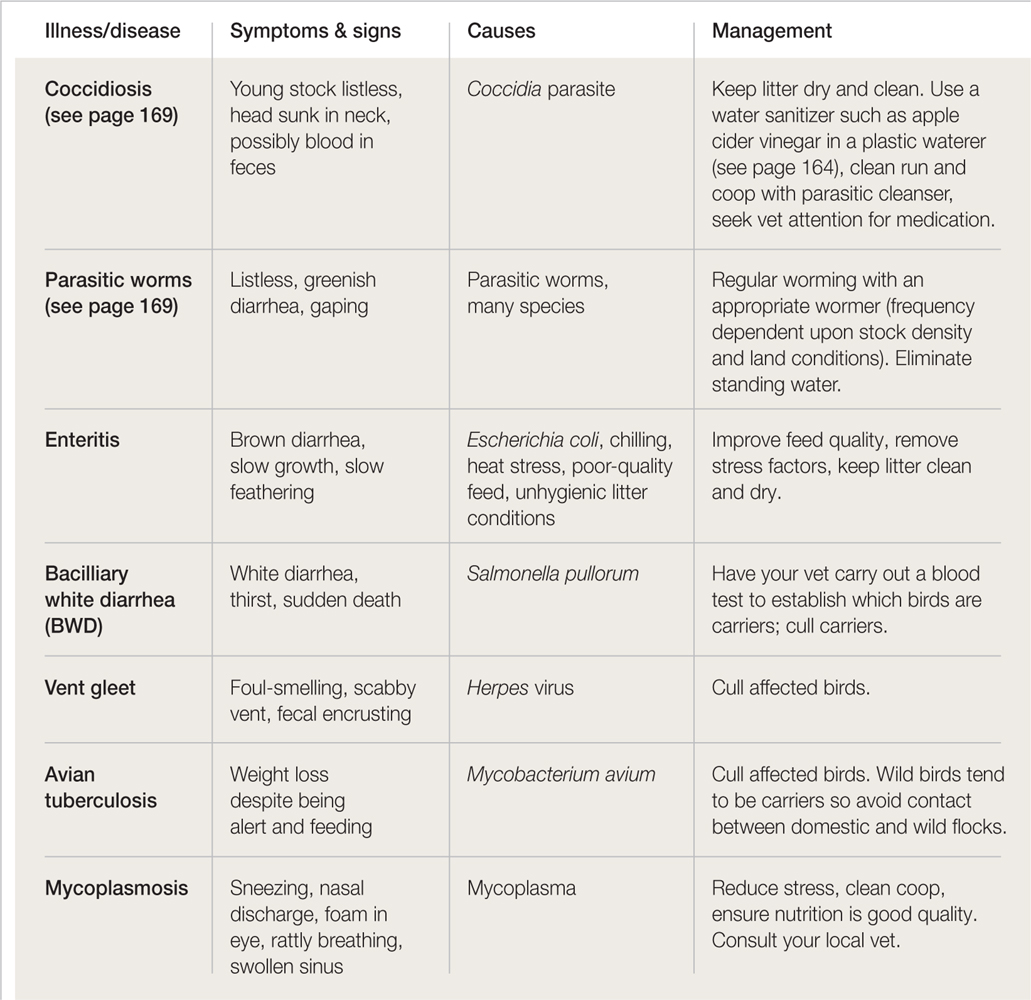

Common Diseases & Health Problems

The table below gives a brief summary of the most common diseases and health problems affecting chickens kept on a small scale. If you have any concerns over the health of a bird or birds in your flock, get in touch with your local vet for a professional diagnosis.

Common Diseases

Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis is a parasite-induced illness that can be debilitating and fatal to chickens. Young growing stock will be exposed to the parasite (Coccidia protozoan) at some point their lives, and they will usually develop an immunity to it, either because the exposure is at a low level or because they have survived the resulting illness.

Artificially reared birds can be particularly at risk of contracting the condition when they are first put outdoors. The outward signs of the disease are a hunched, fluffedup bird with drooped wings; it can also present itself as blood in the droppings of the bird, although this doesn’t always occur. The condition can be confirmed by having fecal samples tested by a vet. A rapid response to tackling the problem is required, as it can very quickly spread throughout the whole flock when the infected droppings come into contact with uninfected birds, potentially wiping out a batch of young birds within days. Keeping ground litter dry and clean can help prevent its occurrence, but cleaning the coop and run with a suitable parasitic cleanser and using an oral medication supplied by a vet will be required in the event of an outbreak.

Parasitic Worms

Chickens are no different from most other animals in that they are susceptible to infestation by parasitic worms that have evolved to exploit them. The two groups that are significant to chickens are flatworms (cestodes and trematodes) and roundworms (nematodes). Both of these types of worms live within chickens, feeding off their host and reproducing while protected from the outside world.

An infestation of worms can reduce the nutrient uptake of the chicken and disrupt its immune system by creating an additional burden. In most cases, chickens will develop a level of resistance to worm infection, though if the flock is kept on the same area of land, the worm count can increase significantly and the flock may become heavily infested.

Regular worming can be performed using over-the-counter poultry wormers if movement to fresh ground is limited. Additionally, worming in the spring and again in the fall is advisable in order to reduce the risk of other diseases compromising the flock.

The life cycle of coccidiosis

Lice

As with most creatures, chickens can be hosts to a wide variety of lice. There are around 50 different types of lice that can affect chickens, with different species exploiting different parts of the body. In general, they tend to be small parasites that scuttle around on the skin of the chickens and hence can be quite difficult to spot. It is therefore important that the keeper performs a thorough inspection of the bird when it is in the hand, paying particular attention to the base of the feather shafts, as this is frequently where the lice eggs (or nits) can be found.

In most cases, lice tend to be more of an irritation than a direct life-threatening risk, although, if not dealt with quickly and effectively, heavy infestations can cause extreme stress and possible fatality in a flock.

As the lice life cycle is invariably spent entirely on the host, treatment is usually applied directly to the chicken with the application of a suitable insecticidal louse powder. Ensuring that the birds also have a dust-baths will also help them tackle the problem themselves, especially if the louse powder is added to the bath.

Tip

Keeping grass short leaves few hiding places for smaller microscopic pests such as parasitic worm eggs, which don’t survive well when exposed to UV light rays. It also means the area is a little more exposed and less welcoming to larger predators. Don’t denude the run, but keeping some of the grass and scrub in check will help control pests and predators.

Red Mite

The red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae) is a pest of the summer months, and, while it may not be active during winter weather, it has an incredible ability to survive long periods without feeding.

The parasite takes up residence within the chicken coop and usually completes its life cycle off the bird, living in crevices or cracks in the structure of the henhouse. It gets its sustenance by sucking the blood from the chickens as they roost at night, before returning to the crack from which it came. Red mites can breed and multiply at an incredibly rapid rate, completing their maturation from egg to egg-laying adult in a matter of days. If left unchecked, their resulting population can be so large that the quantity of blood they take from a bird overnight can result in anemia and even death. A red mite can survive more than six months without feeding, and, while a really harsh winter may kill off adult mites, the eggs they laid late in the summer will live on, ready to hatch at the first signs of warm weather.

A red mite infestation is notoriously difficult to get rid of once it has taken hold of a coop. A regimented cleaning and treatment program is required over a number of weeks in order to try to break the mite’s life cycle. It is far better to act quickly as soon as the parasite’s presence has been identified.

A simple method of checking for red mites within a coop is to place a bunch of drinking straws at floor level in the corner. Each week, remove the straws and blow through them into an empty jar. If mites are present in the henhouse, they will probably take shelter in the drinking straws and will be seen crawling around in the bottom of the jar.

Alternatively, place a piece of corrugated cardboard at floor level, with the corrugated side face down. If red mites are present, they will take up residence in the cavities of the cardboard.

Northern Fowl Mite

Another mite to be aware of is the northern fowl mite (Ornithonyssus sylviarum). Chickens infested with the parasite tend to have a sunken stance and a greasy appearance to their feathers. Picking up the chicken and parting the feathers at the base of the tail will usually reveal the mites crawling over the skin. Beware—they will also crawl onto your hand, seeking you out as a potential host, and while this will cause only a minor irritation, it is unpleasant and runs the risk that the mite is transferred to another bird or flock. Northern fowl mites become far more active during winter because they prefer cooler climates, and they usually infest male birds in preference to females, although both sexes are susceptible to attack.

Once northern fowl mites find a suitable host bird, they will multiply at an incredible rate and, like the red mite, they are blood suckers. Unlike the red mite, however, these parasites complete their entire life cycle on the birds, are far more aggressive, and feed around the clock. The greasy look of the feathers is caused by their fecal deposits and is usually a strong visual indicator of an infestation. Treatment needs to be rapid and is usually achieved by washing the bird with a medicated shampoo. The rapid reproduction and voracious feeding habits of the mites mean they are capable of killing a bird within a matter of days if the infestation isn’t dealt with immediately.

Scaly Leg Mite

A less lethal but equally irritating poultry pest is the scaly leg mite (Knemidocoptes mutans). An infestation of these mites is difficult to identify until it is well underway. The tiny flat-bodied parasite is not usually seen, but the consequences of its presence are easily visible. The mite lives under the scales on the legs and feet of chickens, and over a period of time the scales begin to lift and crust over. This can cause the legs to thicken and become scabby in appearance, which is usually the first indicator of a scaly-mite problem. As with other mites, quick action is required. Both the infested bird and any others it has come into contact with should be treated because the mite is primarily transferred through direct contact between chickens.

Red mite, the poultry-keeper’s nemesis, can kill if left unchecked.

Every poultry-keeper should have a first-aid kit containing a selection of items, some of which will probably be needed at least once a week. It is useful to keep them together in a bag or box so they are handy, which also makes it easier for anyone who cares for your birds while you are away.

FLASHLIGHT

It’s often easier to handle and treat chickens after they have gone to roost, as they then tend to be much calmer and easier to handle. This does, however, mean you will be working in the dark, so you will need a flashlight. Investing in a good-quality flashlight, particularly one with adjustable beam strength, will mean you have both hands free to deal with the chickens.

SCISSORS

A strong, sharp pair of scissors is needed for cutting string and bandages. Most of all, scissors are needed to clip flight feathers if you have a flighty chicken in your flock that keeps jumping out of the pen (see here).

TOENAIL CLIPPERS AND NAIL FILE

Most chickens will keep their toenails worn down by scratching around, but birds kept indoors or on soft ground may require a bit of a pedicure. In addition, some cockerels do need to have their spurs attended to (see box on here).

PLIERS OR WIRE-CUTTERS

These are not only useful for emergency fence repairs, but are also ideal for quickly removing plastic leg rings (see below).

LEG RINGS

Having a range of different-colored and different-sized leg rings on hand means you can quickly and easily “mark” an individual chicken. This is particularly useful if you are administering treatments to the flock and need to separate those that have been treated from those yet to be dealt with.

FEEDING SYRINGES

A collection of different-sized feeding syringes is essential when you need to administer fluids such as medicines down the throat of a chicken.

DISPOSABLE LATEX GLOVES

Gloves are not needed often, but when it comes to vent-related problems such as a prolapse or vent gleet (see here), they can make the task much easier for the keeper (and probably more comfortable for the chicken, too).

A veterinary antiseptic spray is ideal for treating minor wounds and can also double up as a deterrent spray on feathers in minor cases of feather pecking.

GENTIAN VIOLET SPRAY

This spray, popular in the UK, works in much the same way as the veterinary antiseptic spray, but it has the advantage of being visible. This means that it can also be used to mark birds quickly and temporarily either after treatment or for further selection. Don’t use it on chickens you intend to exhibit as it can be difficult to remove fully.

PETROLEUM JELLY

Not only does this serve well as a lubricant for sticky hinges and locks on the henhouse, but it can also be applied carefully to the combs of birds during extremely cold weather to reduce the risk of frostbite, and to dry patches of skin on their faces or legs. It is also handy when treating scaly leg mite on chickens should they become infested with the parasite (see here).

COTTON SWABS

Cotton swabs are useful for delicate tasks such as cleaning around the eyes or nasal passages of birds.

PET CARRIER OR DOG CRATE

You can never have too many pet carriers for transporting or quarantining your chickens. Plastic dog or cat carriers are ideal for single or even small numbers of chickens, but be sure to disinfect them thoroughly after each use to avoid any possible transferral of pests or diseases to other chickens.

Finally, make sure your vet’s telephone number is readily available at all times. While you may not necessarily need it, it could prove invaluable if friends or neighbors look after your stock while you are away.