CHAPTER EIGHT

Your Egg-Laying Flock

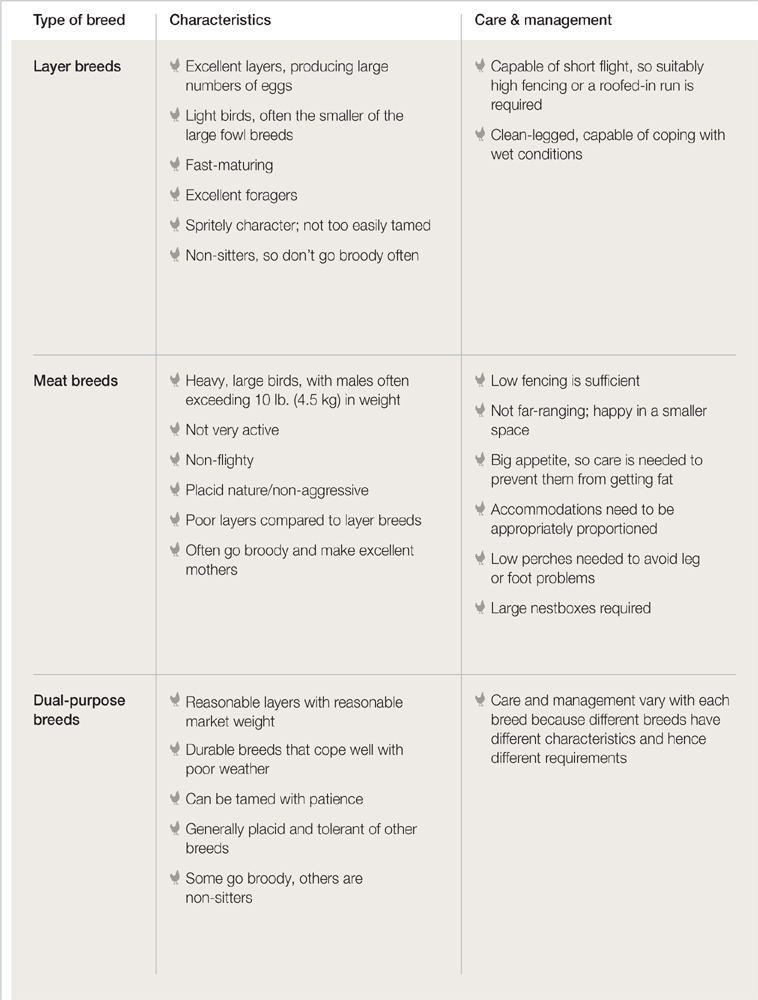

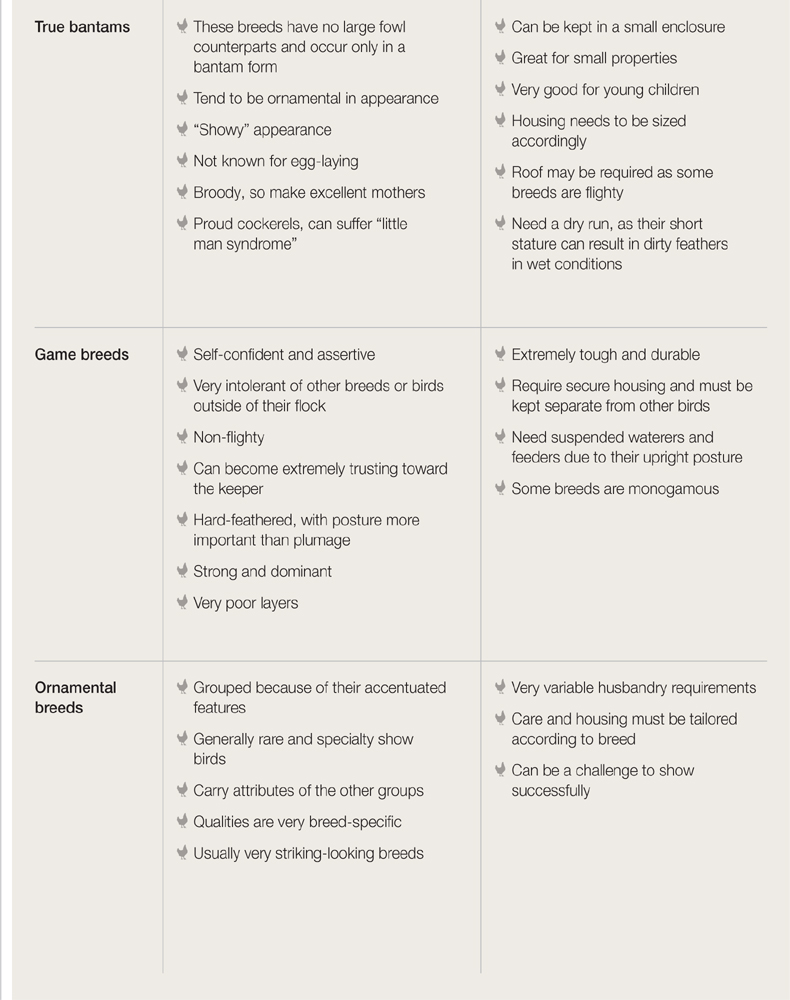

Chicken breeds loosely fall into six categories or classifications in terms of their function or purpose: layer, table, dual-purpose, true bantam, game, and ornamental breeds. There is some blurring of lines between the different breed types and there are even breeds that have made a transition from one type to another at some point in history, or could arguably be placed in more than one group.

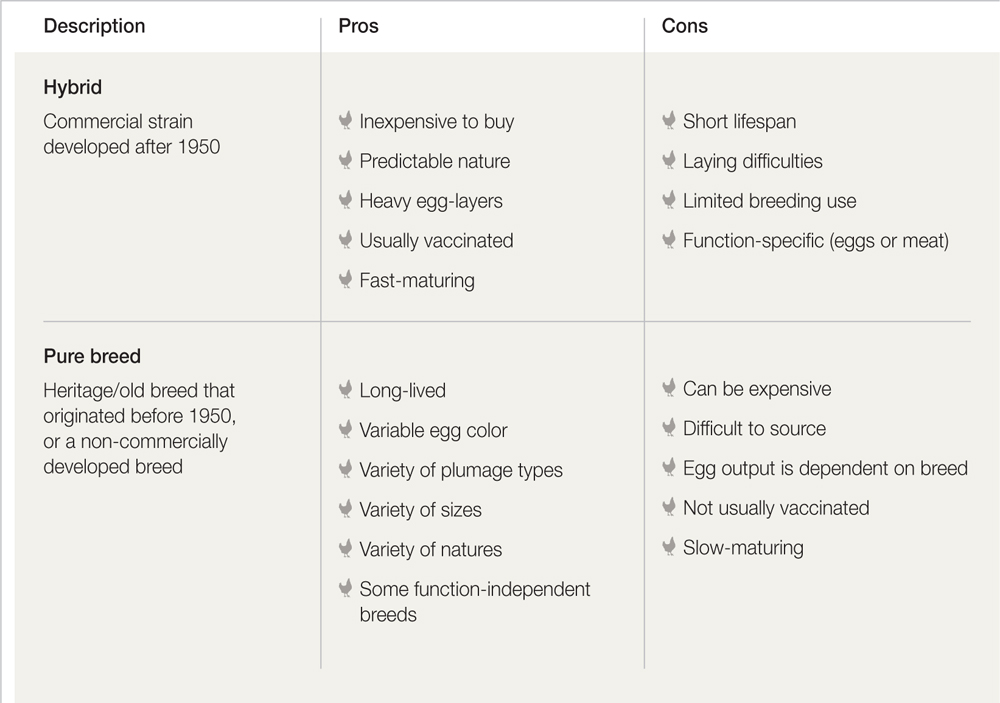

There is also another widely recognized division between pure (or heritage) breeds and hybrid chickens (see table below). Pure breeds tend to have been developed through many decades of careful breeding. The definition varies according to different countries and different organizations, but as a general rule of thumb such breeds have been recognized since before the mid-20th century (pre-1950).

A hybrid is an intentional crossing of different breeds of chicken with a specific end game in mind of either fast-growing table birds or more efficient and cost-effective egg-layer birds. Hybrids have generally been developed since the 1950s, which was a key time period in the development of many of the commercial strains we now encounter on large-scale poultry farms.

Chicken Classification—A Quick Guide

Pure Breeds & Their Specialties

Chicken breeds that fall within the layer category, be they hybrid or heritage, are capable of producing large numbers of eggs. They are usually smaller in size than those that are bred for meat or those that sit within the dual-purpose category. The reason for this is simple: they put their energies into laying eggs, not into putting on body mass. They also tend to come into lay sooner than the other types of chicken, the intent being to have them reaching maturity by 20 weeks of age and to lay as many eggs as possible within the first few years.

Layers are often excellent foragers, scratching and digging industriously for additional tidbits, a trait that contributes to their efficiency by minimizing the feed costs for maximum output. Their nature is often sprightly, though shy, and some breeds can be very wary of their keepers, who need to show a patient and relaxed approach if they are to tame the birds successfully.

Many of these breeds also fall into the “non-sitting” category, meaning that they rarely go broody. The trait of broodiness is not favored in laying breeds, and over the centuries it has been selected out through careful breeding. If you intend to raise laying breeds from fertile eggs, alternative hatching methods may be needed, such as an artificial incubator (see here) or a willing broody hen of a different breed (see here).

The key quality of a layer breed is the volume of eggs it can produce. For purebread layers, this is often viewed as the ability to lay more than 200 eggs a year (ideally more than 280 for the best individuals in a flock). For commercial hybrid strains, this figure exceeds 300 eggs in the first year of production (but achieving this needs careful management of the environment and can have health consequences for the birds themselves).

Historically speaking, up until fairly recent times, almost all domesticated chickens were viewed as egg-layers. The primary purpose of the chicken was to lay eggs, and lots of them. This took priority over the provision of meat for the table, and only when the bird ceased being productive would it be culled and used for food. Many countries and regions carefully developed their own specific purebred egg layers to suit their local environment. As a consequence, there are a wide range of heritage or pure breeds with an equally wide-ranging history. Some, such as the Lakenvelder (see here), date back to the early 18th century, while others, such as the New Hampshire (see here), emerged as a breed only in the early 20th century.

Tip

It is important to note that the egg output of a particular hen can also depend on its bloodline. Many of the breeds, or colors within a breed, that were once excellent layers have changed over the years, having been developed for exhibition—examples include the Leghorns and Orpingtons. Although individuals and bloodlines within these breeds may appear the same, they might have lost their high egg production, so check with the seller before you purchase any stock.

In general, layer breeds tend to be lighter in the body, more agile, and, in some cases, quite capable of short flight. As such, high fences or roofed-in runs need to be considered to stop them from straying too far. They are predominantly clean-legged, so will cope better in wetter conditions than those with foot feathering.

The breeds are designed to lay daily for as long as the daylight hours allow, so it is good breeding practice to weed out the poorly performing individuals within a flock if you intend to breed replacements. Birds that have good feathering toward the end of the season or those still laying eggs with heavy pigmentation will be infrequent layers and should not be bred from. In contrast, a bird that has laid well during the season will have shabbier feathering and a decreased ability to color her eggs at the end of the season. Her productivity will make her a good hen to breed from if egg production is the sole objective.

The Victorian craze for fancy fowl in the mid-19th century significantly changed the Western perspective on chickens. In fact, it undeniably put poultry in a new light within modern culture. No longer were they simply a “farmyard forager”—they now had a different and wider appeal, which was reflected in “hen fever” cutting across the classes of the Western Hemisphere.

The influx of new breeds not only delivered aesthetic appeal and price tags beyond anything seen before, but also egg-laying and meat capabilities that raised economic eyebrows both at homesteads and, later, at a commercial level. It was both of these practical functions that would become more pivotal over the next 100 years.

The austere times that were brought about by the two world wars put meat among many other things in short supply and it was the chicken fanciers of the time who, unknown to them, held the answer. They had already developed certain breeds and strains that had the potential to provide plenty of eggs and meat, and the fact that such development was occurring in a non-commercial manner meant the path of the humble chicken (and chicken breeder) now split into distinct directions: one as an exhibition hobby, tipping its hat to the late 19th century; and one as a potentially mass-produced food keenly needed by the world’s population.

No more so was this better defined than in the late 1940s, when a collaboration between farmers, breeders, and suppliers, backed by cash prizes from the A&P supermarket chain, launched the Chicken of Tomorrow contest across the US. The concept behind the contest was to challenge the huge numbers of chicken breeders across the country to produce the ultimate breed of meat bird—in other words, one that could provide the most meat in the shortest time and for the lowest feed cost (see here).

Throughout the world, poultry started to be used as an alternative source of protein. Hybridization through careful selective crossbreeding, coupled with a better understanding of the biology and genetics of poultry, meant that breeding programs could be constructed to pursue two discrete results: egg-laying “machines” and fast-growing meat sources. The heritage breeds were soon forgotten in the pursuit of cheap food, and it was left to the exhibition poultry breeders to maintain the gene pools.

Today, science and agriculture continue to work hand in hand with the supply chain to meet the ever-increasing demand for poultry-based products. More and more hybrids were, and still are, being developed to meet specific consumer requirements, and in less than 100 years we have shifted from hen fever to a time when chicken meat and eggs are now staples of everyday diets worldwide. It’s a revolution in agricultural practice driven onward by consumer demand, and now almost forgotten in its wake sits its bedrock, the breeds of the show bench whose history now puts their much-needed conservation in context.

CROSSBREEDS & HYBRIDS

When venturing into chicken-keeping for the first time, and particularly when the objective is to have a good supply of fresh eggs for the kitchen, it is likely you will encounter people saying, “Get some hybrids. They’re an excellent beginner’s bird and filled with hybrid vigor, unlike the pure breeds.” But be careful before taking the plunge on this count, as the commentary might not be backed by the science. Advocates of this approach may be inadvertently basing their claim on heterosis, or “hybrid vigor” as it’s more commonly known, and consequently confusing the concepts of crossbreed and hybrid.

A crossbreed is generally any offspring that is the product of a mating between a cock and a hen of two different breeds. It is usually the product of an “accidental” mating of the two different breeds rather than a premeditated mating aimed at introducing a genetic trait into a comprehensive long-term breeding program.

A hybrid, on the other hand, is the offspring produced when two different breeds or strains of chicken are intentionally crossed. These chickens themselves may not be pure breeds but a generation of hybrids. Hybrid breeding tends to be performed with a specific end game in mind; this could be for the production of a fast-growing bird for the table or an improved egg-layer. As such, commercial broilers and egg-layers are hybrids. They are fast-maturing and short-lived, with broilers rarely exceeding 10 weeks of age and egg-layers usually depleted (destroyed) once they have fulfilled one year of egg production. In reality, the term “hybrid” generally refers to all strains of chicken developed after 1950. As such, they have a very specific commercial application and turnover that is not always suited to the small-scale or hobby keeper.

Hybrids have pushed many heritage breeds to the point of extinction.

When commercial laying hens come to the end of service (generally when they are around 18 months of age), the farm usually removes them and replaces them with new pullets that are approaching point of lay (POL). In most circumstances, the depleted stock are destroyed, but there are organizations that “rescue” the hens and then offer them to people to rehome.

The concept of taking a beast from a life within a factory farm and giving it the chance to live out a more natural existence could be said to be admirable, fulfilling, and compassionate, and in many respects it is. However, before taking on rescue hens, it is important to understand the situation fully.

The breeds used within commercial food production are not like other breeds of chicken. For a start, they don’t have names like Orpington or Leghorn, but more often names that resemble car makes and models, like Hybrid V56N. They are often produced by genetics companies that provide detailed reports referring to the “product performance.” These chickens are specifically created to serve a purpose and are frequently accompanied by a product sheet rather than a breed profile.

These “products” are designed with a fixed shelf life in mind. At no point is there any consideration, or need for consideration, beyond the point of depletion. The design brief for them would read something along the lines of “Reach maturity as rapidly as possible, lay as many consistently sized eggs as possible, and do it with the most efficient feed conversion ratio within the first year of laying. Replace when peak performance drops.”

Anyone who has rehomed commercial laying hens will have experienced the incredible transformation they go through, and no doubt this inspires others to do the same. However, before you do so, it is important to have a full knowledge of the potential problems. Commercial breeds are designed to be egg-laying machines, and even after their rate of laying drops below commercially acceptable numbers, they will continue to lay at such a rate that they run the very real risk of laying themselves to death. Additionally, in later life, they can develop all manner of health problems.

There is much to be gained from rehoming these “products” and letting them be chickens. Yet it is important to be mindful that the accelerations in poultry science mean the creation of egg-laying hens designed for indiscriminate depletion has become acceptable. Anyone embarking on giving such hens a new lease of life must be prepared to act humanely if necessary.

The market share of free-range eggs has increased significantly in recent years because larger numbers of consumers have become more concerned about where their food comes from and, in particular, the ethics of egg production. This groundswell has resulted in a much wider understanding of the production chain, but only in terms of the manner in which the laying hens are kept and the environment in which the eggs are being produced.

The wider picture is more complex, because for every hybrid laying hen that hatches, there is a hybrid male—in other words, half of all chicks that hatch are male and half are female. What many people don’t realize is that these male chicks are invariably slaughtered on day one because they serve no commercial purpose.

No matter how ethically sound the husbandry system in which the resulting pullets are kept, the reality is that hybrid male chicks from those strains designed for egg laying rarely survive beyond hatch day. This is because the egg-laying hybrid is designed specifically for egg production and so does not fatten up, meaning that the males do not make an economically viable source of meat. The issue of what to do with the male chicks from these hybrid strains is not wholly ignored by those responsible for their future, with some significant research being applied to genetically modifying the chickens further. An example of this currently involves the potential of adding genes from jellyfish into the hybrid strain. This makes it possible to identify the female embryos within the shell as the introduced gene causes them to fluoresce under UV light. The advantage of this is that the males can be disposed of prior to hatching, thus not only removing the issue of destroying millions of male chicks but also saving both money and the greenhouse gas-emitting resources expended in incubating the male eggs to hatching point.

If it’s possible to put aside the ethics of killing the male embryos and any strength of opinion regarding genetic modification, this could be valid solution to the problem. However, there are potentially better solutions. For example, a major commercial poultry breeder is trying to develop a breed of chicken whose females not only lay well but whose male offspring have good table properties—in other words, tapping into the real value of dual-purpose breeds. To a small farmer, the dual-purpose breed is not only economically sensible but also ethically sound, where nothing is wasted and everything serves a purpose. It is worth considering this wider picture when deciding on which chickens you intend to purchase.

One of the best times to pick up new POL stock, both in terms of bird health and from a price perspective, is late summer onward. This may seem an odd time to buy, with most people probably thinking that spring would be the best, but a bird that is 20–25 weeks old in the summer will have hatched in early spring and will hopefully have been allowed to grow outdoors during the warm summer months. It’s also very possible that the bird will come into lay before the onset of winter and subsequently lay throughout the winter, when older birds are resting or molting. In the spring, any bird at 20–25 weeks of age will have spent significantly longer indoors, possibly under artificial heat/light for a larger part of its growing period, and this can impact the overall quality of the livestock.

In late summer, many breeders will have finished selecting their stock for the next season and exhibition breeders will have picked out their show team, so there will be a lot of surplus stock on the market. Much of the stock will be high quality for the reasons given above, making the prices more competitive than earlier in the season. This provides the clever buyer with a good chance of grabbing a bargain.

STOCK TYPES

Frequently, the stock on sale is described as either show-, breeder-, or pet-quality. These categories are defined as follows.

Show-Quality Stock

An example of a bird that is deemed as being of show or exhibition quality is one that exhibits all the visual attributes required for the standard of that particular breed and plumage type, and that, at the right time of year and when prepared for an exhibition, would stand a chance of being placed and receiving an award. The key points here are visual appearance and standards. These birds should meet the requirements of the show bench, even if they do not necessarily meet the original requirements or intentions in the development of the breed. This is a point worth bearing in mind when setting out to purchase a pure breed, as show-quality birds may serve you well in a show but not in the kitchen.

Poultry auctions provide a chance to grab a bargain.

Breeder-Quality Stock

These birds will have some defect within their features that prohibits them from taking honors at a show, but they do have the genetic makeup and potential to be used to breed a show-winning bird. It is a common misconception that two show winners, when bred together, will automatically produce many more show winners. They don’t and, in fact, rarely will.

Pet-Quality Stock

Usually these are purebread chickens that are sub-show standard and shouldn’t be used as part of a pure-breed breeding program. It doesn’t make them any less of a chicken, and, despite the name, it also doesn’t mean they are necessarily pet-like in their behavior or docile in their temperament. You still need to make sure you select the right sort of breed for your requirements when choosing pet-quality stock.

BUYING ONLINE

The actual sourcing of your poultry can seem a little difficult at first—after all, you don’t often see livestock stores in the local shopping mall where you can stop in and check out what they have to offer. One alternative is the Internet: when it comes to buying poultry, it’s one big storefront offering access to practically every breed of chicken and type of poultry paraphernalia available.

With the breadth of options available on the Internet, it’s easy to see the advantages in terms of access to possible purchases. Images, text, and interaction with the sellers can certainly deliver a level of confidence in ensuring that you are likely to make a good purchase, but there are pitfalls to watch out for. It’s important to remember that all you see and read is “virtual,” and even when you’ve made your decision on which seller to go with and what to buy, you need to apply the same purchasing rigor as if you were buying at a live auction or face to face from a breeder.

There are a number of ways in which the Internet makes eggs and birds available to potential buyers. This can be via auction websites, through trading websites, through individual breeder websites, and through club sites and forums.

Auction Websites

Auction websites either sell hatching eggs or live birds, or some do both. Most don’t require you to register in order to peruse what’s for auction, but all do require you to register if you want to buy or sell. Most, if not all, keep your identity private (at least until the payment stage) and rely on the use of “tags” or nicknames to identify individual users.

The advantage of auction websites really comes into its own when sourcing hatching eggs. These can be sent by mail or courier, which, assuming they are packed correctly, will have no adverse effect on their viability. With careful bidding you can often pick up a bargain, but by the same measure you can waste money on duds.

Livestock auctions are a little different because special arrangements must be made to ship live animals. Sometimes sellers will allow you to visit and see the stock before bidding, something that can certainly help in making a decision to purchase.

Trading Websites

Some websites act as a directory enabling people either to advertise single items for sale or to promote their small businesses (Facebook is also increasingly being used by groups as a method advertising items for sale). Like the auction websites, these can be very useful when it comes to sourcing stock and comparing as many outlets as possible in one place.

Unlike the auction websites, only the seller needs to register in order to place an advertisement. While registering as a buyer will enable you to contact the seller via a messaging system on the site, most of the ads carry direct contact numbers, which negates the need for buyers to register and allows them to get in direct contact with the seller.

Breeder Websites

Some poultry breeders set up their own websites to advertise their business and the items they have for sale, including the breeds they have available and the stock they are carrying. More often than not, contact details are provided, enabling you to get in touch with the breeder directly, either by phone or email, or by visiting them in person. These sites can, however, be more difficult to find on the Internet because they don’t usually turn up at the top of results lists in search engines unless they are affiliated with a larger organization or have exceptionally large numbers of visitors.

Club Sites & Forums

Poultry and self-sufficiency/lifestyle-based websites are also worth checking out. These often have forums where visitors can register and take part in conversations with other members on the site. Some poultry club and magazine websites also use forum technology. Aside from the fact that these forums are a great way to find like-minded people and share knowledge and experience in much the same way as would a physical club, they also usually have “for sale” and “wanted” sections where members can post items. These can be very useful for locating stock or requesting sources for stock, and may also often result in a link back to one of the other types of website already mentioned.

When you have found a seller who has the stock you are looking for, phone, email, or visit them and ask the following questions. Remember that if you are unhappy with any of the answers they give, you are under no obligation to buy. Be patient and be prepared to wait for stock. Good breeders are often small-scale outfits and as such are likely to have a waiting list.

• Ask to see the parent birds and where the young birds were reared. Good breeders will be happy to show you their setup, but do respect their biosecurity measures.

• Ask if and when the birds were wormed and/or vaccinated and what with. Good breeders will keep records and will provide you with details.

• Ask whether there is a return policy. Breeders will always tell you whether the stock they are selling is sexed or not. Mistakes do happen, but a good breeder will exchange or provide a refund in such an event.

• Ask whether there is a guarantee period. Good breeders will allow a period of around two weeks when the birds can be returned for a refund if there is a health problem.

• Always ask to hold the birds and check them over first before committing to buy (see list that follows). Good breeders will be more than happy to have their chickens checked by a buyer before they are sold.

BASIC CHECKS BEFORE YOU BUY

When you are handling a bird prior to purchase, perform the following basic checks:

• Part the feathers, particularly around the base of the tail and around the vent, and check for signs of parasites such as eggs on the feather shafts.

• Rub your hand over the legs of the bird. The scales should be flat against the shanks and not raised or rough, which could be a sign of scaly leg mite (see here).

• Hold the bird up, place the side of the breast to your ear, and listen to its breathing. Any wheezing or rattling could be a sign of a respiratory disorder.

• While holding the bird up, take the opportunity to sniff its breath. There should be little or no smell. Any stronger odor could be a sign of a digestive or crop-related problem (see here).

• Feel the bird’s crop (see here). Healthy birds will be eating and therefore have food in their crop—this should feel like a slightly soft ball. An empty crop or one that feels either solid or squishy are signs of an unhealthy bird.

• Feel the bird’s general condition—it should be firm, not fat or skinny.

• Check that the eyes are bright and the comb is the correct color and that the bird is generally alert and not lethargic.

Again, if you have any concerns, remember that you are under no obligation to buy your chickens from the seller and are free to look elsewhere.

Once you have purchased your chickens, make sure their house is ready and the fencing is secure prior to picking them up. Open the ventilation in the house if it’s not open already and fill the feeders. If you have an outside feeder, either place it inside the coop if space permits or place a small bowl of feed in the coop instead. Also, put a small waterer in the house temporarily. Waterers are generally best kept out of the living quarters because the chickens will invariably knock them over.

Before setting off to collect your chickens, check whether the seller will supply transport boxes. If not, you will need to take along either a sturdy cardboard box or a pet transporter of an appropriate size. Food and water are not essential for the occupants on the journey unless it is going to be particularly long, but try to make the collection time as late in the day as possible to avoid any high temperatures. As you put each chicken into its box, give it a final check to make sure it appears healthy.

When you get the chickens home, check the birds over once again and then place them in the coop. Don’t let them out into the run, but instead leave them indoors with the food and water so that they can settle in. They will roost in the house overnight, and hopefully when you let them out into the run the following morning, they will realize the coop is home and where they should roost. After a couple of days, the waterer can be placed outdoors, along with the feeder if you intend to have it outside.

If you intend to allow your birds to roam free-range, it is worth initially keeping them within a more confined area. This will enable them to familiarize themselves with the immediate environment, with you, and with any other regular presences such as other animals and passing traffic. After about a week, remove the temporary enclosure, and your chickens should be ready to roam.

If you already have chickens, then keep the new stock separate from them for the first two weeks. This is a sensible biosecurity measure and decreases the risk that any disease or parasite may be transferred. After this time, you will be ready to integrate the newcomers into the flock. This can result in a bit of aggression between the new and old as the pecking order (see box on opposite page) is established. Such aggression can be kept to a minimum by introducing the new birds to the coop a few hours after the existing flock has gone to roost. This will at least mean the new birds are able to rest for a night before they attract the attention of the old birds.

In the morning, ensure that more than one waterer and feeder are available, as again this will help reduce aggressive encounters between the two groups of chickens as they take food and water. No matter what measures you take, it’s likely that there will be some aggressive behavior between individuals from each of the groups as the pecking order is established. This is only natural and in most cases the new birds will be subordinate to the existing flock until a more familiar social hierarchy can be established. Occasionally, though, aggressive behavior can lead to outright bullying. This is when there is constant hostility by one bird toward a subordinate bird. In these instances the bully should be removed from the flock and placed in a quarantine cage for a week until the subordinate has the chance to settle. Do not remove the bullied bird (unless you relocate it permanently), as its reintroduction to the flock will invariably result in a return of the original bullying behavior.

Aggression toward people

While aggression between chickens is part of their normal behavior, aggression toward people should not simply be dismissed as dominance or bad temper. In this case, the bigger picture should be considered and, in particular, the behavior of the keeper.

First, if there is a cock in the flock, ask yourself if its hens are persistently being picked up? If it is an all-female flock, is the underdog favored and given more attention and treats than the others? Such apparently insignificant interventions have an impact on the social structure of the flock and could give rise to competition and aggression.

Pecking order

This is the social hierarchy of a flock of chickens and can develop when the birds are as young as six weeks of age. It will determine which birds eat first, which will have the best dust-bathing spot, which will have the highest roost point, and so on. It delineates the dominant from the subordinate, and is usually established through a degree of aggression (pecking). It does, however, create cohesion within the flock structure, which, while competitive in its concept, is also there to minimize conflict.

Pecking orders exist in all flocks, be they single or mixed-sex. In general, if the flock contains a single cock, he will be at the top of the pecking order, followed by a hierarchy of hens. If the flock contains a number of males and females, then the order tends to be roosters or cocks, hens, cockerels, and then pullets, with the members of each group having their own order of rank.

Many factors can influence a bird’s position in the pecking order, and it doesn’t always come down to size or physical fitness. For example, a bird with a large single comb, such as an Ancona, will often find itself higher up the hierarchy than an Araucana, which has only a pea comb, despite the Araucana being bigger in size.

Aggressive behavior between chickens is, in effect, a form of negotiation. Human society has developed negotiation to the point that, in most instances, it is performed using verbal communication, avoiding conflict, although in many cases it will still carry a level of posturing.

Within chicken society, negotiation tends to start with posturing, and, if that doesn’t resolve the problem, conflict will follow, be it a sharp peck, a kick out with claws and spurs, or a full-on fight.

While chickens will invariably establish their own social structure, it is possible for the keeper to assist in keeping it stable and minimizing stress, tension, and unnecessary conflict. This can be done by:

• Providing sufficient feeders and waterers so that more birds have the opportunity to feed or drink at the same time.

• Ensuring that there are always places to hide for the lower-ranking birds.

• Providing sufficient space (see here).

• Minimizing disruption to the pecking order by not adding or removing birds too frequently.

Flock cohesion and structure play an important part in chicken “society.” It is important that the keeper recognizes this.

You will need to create a regular routine of tasks for the care of your chickens each day, week, month, and year (see table on here). While this regime will cover most of your chickens’ requirements, there are particular seasonal considerations during periods of extreme summer heat or cold and wet winter weather.

In both circumstances it is important that shelter from the elements is provided—shelter from the heat of the sun or shelter from biting cold winds and rain. This can be as simple as leaning a fence panel against the side of the coop. Water is another key consideration. Chickens drink quite a lot of water no matter the season. Ensuring that the water you give them is fresh, cool, and free from algal growth in the summer is as important as ensuring that it isn’t frozen solid during the winter.

If the ground gets muddy during the rainy season, provide raised areas for your chickens so they can get themselves out of the mud. And if it snows, clear areas for them—snowfalls deeper than 4 inches (10 cm) are generally considered impassable by chickens.

Wing-clipping

While it is not a requirement to clip the wings of your chickens, you may need to do so if you have a bird (or birds) that persistently clears boundaries and heads off to the neighbor’s backyard or your vegetable plot. Some breeds of chicken are reasonable flyers over a short distance, while others are very good jumpers. Despite clipping, however, some birds will still manage to clear a fence. Wing-clipping is not, therefore, a fix-all, and some sort of netting over the run might be a better alternative.

Wing-clipping is easiest if you have an extra pair of hands to hold the bird. With sturdy scissors, cut off the primary feathers on one wing only. This serves to unbalance the bird and reduce the height it can gain. The primary feathers are not seen when the bird’s wing is closed, so cutting them doesn’t affect the look of a resting bird.

Wing-clipping should be done when the feathers are fully grown and only when the bird is mature. The feathers will remain cut until the bird molts, at which point new primary feathers will grow. Once these are fully grown, you can clip them again, but hopefully by that time the bird will have gotten out of the habit of ranging too far.

Spur-clipping

As male chickens age, their spurs can grow quite large. To help avoid the injury the spurs inflict on hens during mating, and to prevent the spurs from becoming snagged or growing inward toward the leg, it is a good idea to clip them and file them to a blunt end.

Large dog nail clippers make an ideal tool to trim the spurs, although care should be taken not to take too much off. There is a blood vessel running down the center of the spur—usually about three-quarters of the way along it—that should not be cut, as doing so will cause bleeding that can be difficult to stem.

Biosecurity is a buzzword in livestock farming, but it is one that backyard poultry-keepers need to be aware of. No matter how small your flock of birds may be, good biosecurity practices should be followed, not only to minimize the risk of disease transfer within your own poultry, but also transfer to other people’s birds. Below are a few commonsense biosecurity measures to build into your daily routine.

• Keep poultry feed under cover to deter the attentions of wild birds. Ensure that water is always fresh, and clean out waterers at least twice a week, if not more.

• Replace any water that becomes soiled with droppings.

• Quarantine any stock that has been off site (such as to a poultry show) for at least seven days.

• Quarantine new stock for at least two weeks before bringing the birds into contact with existing stock.

• Clean your clothes and boots after visiting another poultry establishment, show, or sale.

• If you have more than one pen of birds, consider using a disinfectant boot wash.

• Don’t share transportation crates or feeding equipment with other keepers.

• Always disinfect transportation crates before and after use.

• Wash your hands before and after handling poultry.

• Keep vermin such as rats under control.

Biosecurity is all about disease prevention. By following these simple precautions, you will go a long way in protecting your flock from infectious diseases.

Dealing with Unwelcome Visitors

No matter what country you live in, there will invariably be a number of local animals that are keen to make a meal out of your flock of chickens. Foxes, badgers, weasels, and even hedgehogs will break into a chicken run and attack chickens if they are hungry enough and if the security of the flock is not strong enough.

It is important therefore to consider the animals in your immediate environment and deploy security techniques accordingly—though keep in mind that some may be stronger than you (bears) or have opposable thumbs (raccoons)! Whichever method you settle on, the following basic principles will help reduce the likelihood of an attack:

• Don’t let the flock out too early in the morning, especially into an unsecured area, as nocturnal predators might still be out. If other animals in the area are keeping quiet, it’s quite possible a predator might be lying in wait. Conversely, noisy wild birds might be a sign that a predator is near.

• Keep boundaries well secured. Predators will look to exploit any weakness, be that a short circuit in an electric fence or a hole dug by a rabbit. It might take weeks for them to find a weakness, but they will find one. You must constantly be on your guard.

• Walk around your flock at irregular times. A pattern to movements is no different than a weakness in your fence, and a predator will quickly learn to exploit it.

• When the birds go to roost, be there to close the door; in fact, be there 15 minutes beforehand to check that all the birds are in and there are no stragglers.

• Be aware that many nighttime predators are totally nocturnal and may also feed during the day.

PETS

Pet cats and dogs can be a concern to a chicken-keeper, and it is always worth familiarizing them with your chickens where possible. Cats will invariably leave large, full-grown fowl alone, though bantams and young growers can be at risk of being attacked and killed. Some dog breeds, such as Collies, mix very well with chickens, happily coexisting alongside them, but other breeds, such as terriers, can pose a risk. The chicken-keeper will need to train the dog to keep away from the chickens, though any dog that expresses an unhealthy interest in a flock should never be left alone with it.

If you do not have a dog but have visitors who bring their pet along, politely point out that while their dog might not be bothered by the chickens, they will be bothered by him. If they are not familiar with dogs, most chickens are intelligent enough to view them as a predator threat.

Rats are fairly ubiquitous creatures and can be an issue for the chicken-keeper year-round. They are a particular nuisance in winter, when the cold weather sees them struggling for food and shelter and potentially seeking out a cozy chicken run until the weather improves.

Having rats in your chicken run is not a sign of poor husbandry, but it is poor husbandry not to deal with the problem once identified. Rats need three things—food, water, and shelter—so by removing at least one of these requirements, there’s a good chance you will remove the problem. Don’t leave feeders outside; either bring them indoors or put them inside the chicken coop at night. Empty the waterers each night and refill them in the morning. Finally, raise the coop off the ground, if possible by at least 6–8 inches (15–20 cm), to prevent rats from nesting underneath it (this has the bonus of providing an outdoor shelter or new dust-bath location for your chickens).

Rats present a limited predator risk and are only likely to attack young growing birds or very small bantams. There is also anecdotal evidence that rats will be attracted to the coop in order to steal eggs. There is the possibility that small bantam eggs could be taken by a rat, though eggs from large fowl, especially when located in a nestbox, are too awkward for a rat to move. If a broken, half-eaten egg is found in the nestbox, the finger of suspicion should be pointed elsewhere first.

AVIAN PREDATORS

Crows are very intelligent birds and are not afraid to enter a chicken coop and help themselves to any food, particularly the eggs inside. The will usually try to consume the egg in situ, especially if access to and from the coop is restricted. This can result in a broken, half-eaten egg lying around, which could in turn attract the unwelcome attention of a chicken that may then pick up the difficult-to-break habit of egg-eating (see here).

To reduce the likelihood of crows or other corvids entering the henhouse, simply place a loose material screen cut into strips over the door of the pop-hole or entrance to the nestbox once your chickens have gone in to roost. Come the morning, the chickens will work out how to brush past the material and will enter and exit the coop as if it had always been there. If the sheet is put over the nestbox, the chickens will appreciate the additional darkness and privacy it provides when they are laying. Crows, on the other hand, are unlikely to enter the coop or the nestbox because they seem to avoid doing so unless they can see a clear exit.

Small backyard birds are unlikely to present a direct danger to your chickens, but they will steal food and can carry pests, such as lice and mites, into the coop and run area. Using small-gauge netting or wire around and over the run will keep them out. If your chickens are free-range, however, contact between them and wild backyard birds is inevitable at some point, although food theft can be reduced by making use of a treadle feeder (see here).

Larger wild birds, such as birds of prey, have been known to attack and take chickens for food. Roof nets can be added to the runs of flocks kept within a confined space to stop any chance of attack, but free-ranging chickens will be at risk if large birds of prey are present in your area.