In 1942, the government’s Office of Civilian Defense distributed a pamphlet entitled “What Can I Do?”

It promised “V-Home Certificates” to “those families which have made themselves into a fighting unit on the home front.” The V-Home certificate reads:

|

We in this home are fighting...we solemnly pledge all our energies and all our resources to fight for freedom and against fascism. We serve notice to all that we are personally carrying the fight to the enemy, in these ways: |

I. |

This home follows the instructions of its air-raid warden.... |

II. |

This home conserves food, clothing, transportation, and health, in order to hasten an unceasing flow of war materials to our men at the front. |

III. |

This home salvages essential material, in order that they may be converted to immediate war uses. |

IV. |

This home refuses to spread rumors designed to divide our Nation. |

V. |

This home buys War Savings Stamps and Bonds regularly. |

|

We are doing these things because we know we must Win This War. |

On December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor and long before “What Can I Do?” appeared, PM editor Ralph Ingersoll exhorted his staff: “Today we begin a new task...WINNING THE WAR.” Dr. Seuss performed yeoman service in that cause. Most of Dr. Seuss’s cartoons after Pearl Harbor had as their purpose building morale to win the war.

During his two years at PM, Dr. Seuss drew four cartoon series: the lampooning of Virginio Gayda that we examined in the first chapter and the Society of Red Tape Cutters, both repetitions of the same drawing, albeit with different quotations or honorees; the “Mein Early Kampf” series depicting Hitler as a baby; and the “War Monuments” series in January 1942.11 188 87 There are also several cases in which Dr. Seuss used the same title for two separate cartoons.195-199 “War Monuments” is both the most ambitious series and the most successful. Here Dr. Seuss spelled out the themes of much of his campaign on the home front. The series is drenched in satire.195 The first “monument” (January 5) is to “John F. Hindsight, master strategist of yesterday’s battles, famed for his great words, ‘We coulda.. + We shoulda..’” The statue has Hindsight leaning back in a rocking chair, legs crossed, squinting through a telescope that takes a U-turn to aim directly behind him. Two bemused onlookers underline the sarcasm. The second “monument” (January 6) is to “Walter Weeper: generously over-subscribing his quota of tears, he enabled others to furnish the blood and the sweat.”196 On his shoulder, a stone bird adds his tears. Once again, two onlookers seem to speak for the artist.197 Two days later (January 8) came “Dame Rumor, Minister of Public Information.” Two housewives gossip over a clothesline, in the process divulging alarmist misinformation. In the background, a group on a tour bus looks on as the guide holds forth. (Note with what economy Dr. Seuss establishes the setting—New York, likely Central Park.)

The fourth “monument” appeared on January 13: “To JOHN HAYNES HOLMES who spoke the beautiful words: The Unhappy People of Japan are Our Brothers!’ “ The statue is of an orator (head not visible) standing with left arm in the breast of his jacket and right arm around the shoulder of “Japan.”198 “JaPan” has a jury-rigged halo over his head, and in his right hand he holds a dagger and a severed head. Unlike the cartoon depicting Japanese Americans lining up to receive bricks of TNT, this cartoon drew angry response from many readers (“Letters to and from the Editor,” January 21 and 28, 1942). Some of them spoke up for John Haynes Holmes, a prominent Protestant pacifist minister. Some protested on more basic grounds. Wrote one: “I protest the Dr. Seuss cartoon on John Haynes Holmes.... Beyond the sheer bad taste is something even deeper. That is, the implied rejection of the basic Christian principle of the universal brotherhood of man.” Wrote another: “I am not a pacifist, but I do not need to be one to find myself in complete sympathy with Dr. Holmes’s belief in the essential brotherhood of man. For what else are you fighting, PM?” A third spoke of “PM’s grotesque incitement to hatred. It’s OK to remember Pearl Harbor; why not remember our war aims, too?” A fourth: “In my abysmal ignorance the thought that the Japanese people (and all people for that matter) were no worse than and no better than any other people on the globe was deeply etched in my mind. The absurd notion that the common people of these war-driven countries, the working masses, were the first real sufferers of a terroristic Fascist-capitalist regime has been replaced by the scientific actuality that those people are inherently militaristic and savage as suggested by your Dr. Seuss.” A fifth: “Your Dr. Seuss has long been a thorn in PM’s pages.... If the Japanese people are not ‘our brothers,’ what are they to us? Our ‘mortal enemies’?”

To the letters Dr. Seuss responded Jan. 21, 1942 (ellipses in original):

In response to the letters defending John Haynes Holmes... sure, I believe in love, brotherhood and a cooing white pigeon on every man’s roof. I even think it’s nice to have pacifists and strawberry festivals...in between wars.

But right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: “Brothers!” It is a rather flabby battlecry.

If we want to win, we’ve got to kill Japs, whether it depresses John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left.

— Dr. Seuss

Letters continued to come in, con and pro. On the con side: “Dr. Holmes is against those who push other people around—and therefore is for the people of Japan as you should be. Disagreement becomes possible only as to the best methods of relieving them of their Fascist oppressors—or helping them to help themselves.” And pro: “More power to Seuss’s cartoons. They’re well done, original and carry a real meaning. Why don’t those pacifists stop trying to ‘keep their Holmes fires burning.’” In their biography, the Morgans report that Dr. Seuss “was stunned by the virulence of the backlash from isolationists. He had spurred Americans into war, they argued, because, at thirty-eight, he was too old for the draft; his battles were only on paper.” This may be Dr. Seuss’s recollection (the Morgans don’t give a footnote for this passage; it is not absolutely clear that this recollection applies specifically to the issue of John Haynes Holmes), but these critical letters in PM are hardly from isolationists.

The fifth and final “monument” is to “Wishful Listeners: They Spent the War Listening for the Sudden Cracking of German Morale.”199 Four men, hands to ears, listen in the direction of Germany (a helpful sign points “To Germany”); one carries a banner, “It won’t be long now!” A Seussian cat (also part of the statue) holds an ear trumpet in the same direction, while a Seussian dog leads its nonplussed master past the base of the statue.

Let’s look more closely at Dr. Seuss’s effort to win the war. It occupied Dr. Seuss both before and after the “War Monuments” series. There are three general categories: effort, unity, and the economy.

Effort is obviously a crucial factor on the home front. Defeatism is a grave danger. So is over-optimism. Doing nothing, letting others do the heavy lifting, going about business as usual: all work against the common good. Dr. Seuss set out to illustrate these dangers. Doing nothing included, of course, taking no action against Hitler; that was a major part of Dr. Seuss’s attack on the “isolationists.” On a PM cover of May 8, 1941, Dr. Seuss drew “Uncle Sam” talking at full steam—talking and not doing.200 Note how long the eagle’s neck is, how conveniently his wings become hands with thumbs he can twiddle, and how happy he appears. In late August, Dr. Seuss drew the third of three cartoons (two, not included here, appeared in July) dealing with aspects of the American army.201 It attributes low morale in the military to low pay. Doctors examining a draftee with the aid of an x-ray machine see ribs, spine, arm bones—and empty purse: “He has Pursis Emptosis, or Empty Purse...a disease that’s very very bad for Morale!” Neither “empty” nor “purse” has Latin roots, so “Pursis Emptosis” is Dr. Seuss-speak, pure and simple. At the end of August, President Roosevelt signed the first supplemental defense appropriation bill. The eagle’s neck is back to normal size on September 25—more than two months before Pearl Harbor—in “Stop Wringing The Hands that Should Wring Hitler’s Neck!” Says a despairing “Uncle Sam,” “The democracies are finished! Ah Woe!” Once again, wings end in hands that boast fingers, even fingernails.202 In November, “Windbags of America” hold forth as the world burns.203 It is a classic portrait of civic leaders; each holds pages of speech. Wearing a fireman’s hat, “Uncle Sam” heads for the conflagration, but he has to drag the “Windbags” along, too.

Dr. Seuss was a genius at ridiculing pomposity and pretensions. In these cartoons he did so time and again. On December 16, 1941, less than ten days after Pearl Harbor, he depicted a chubby man leaning back in his armchair, bow tie on and martini in hand, saying: “Now let ME tell you what’s wrong!” The title: “You Can’t Kill Japs Just by Shooting Off Your Mouth!” Two weeks later, in “The Battle of the Easy Chair,” a man of leisure tells his manservant, “Wake me, Judkins, when the Victory Parade comes by!” He holds one flag in his hand; another is under his arm.204 205 He wears buttons that read “V”, “Hooray for Our Side,” “Hitler Can’t Take It!” and “We Can’t Lose,” but it is perfectly clear that he himself is not about to take any action at all. In January and February, the papers are full of discussion of military training, expansion, appropriations.206 In February, Dr. Seuss helped recruit men of action as pilots for the U. S. Army Air Corps (the Air Force was not yet an independent service). The exhortation reads, “Out-blitz the Blitzer! Fly for Uncle Sam!” A monstrous four-engine plane with thirteen cannons large and small bears down on a worried Hitler in his Piper Cub.

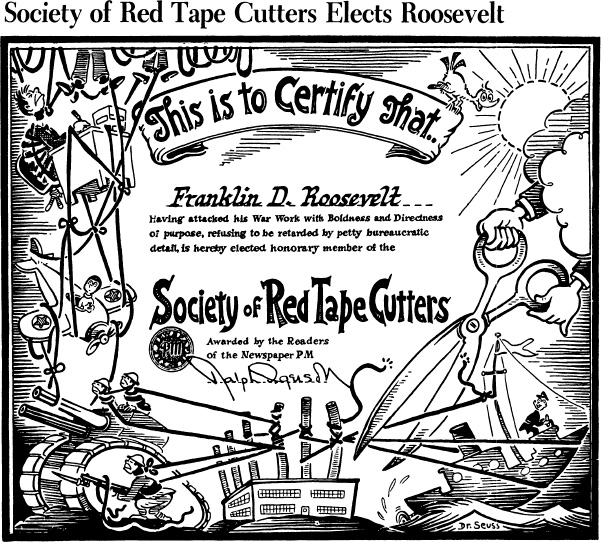

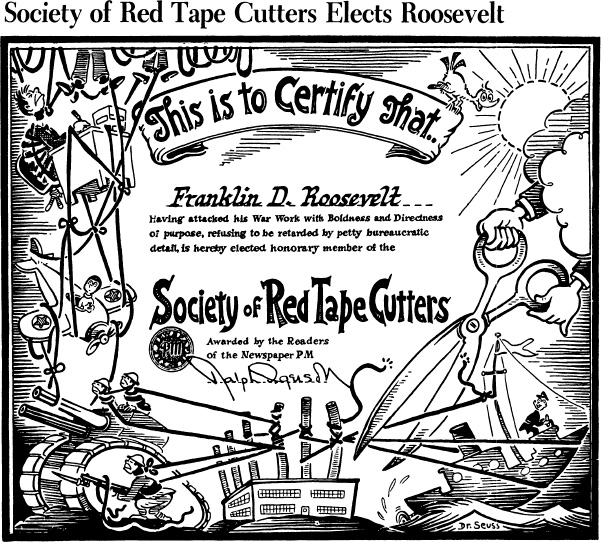

Several cartoons on the theme of business-as-usual deserve careful study.207 In “Red Tape” (February 3, 1942) Dr. Seuss traced water on its way from a hydrant to a fire, which he labels “The War.” A first man (coat, tie, and hat) labors with a hand pump to bring water up into a wooden tank. A second man (top hat, bow tie, jacket, vest) scoops the water into a sieved container over a second tank, which empties in turn into buckets. Three men (top hats, suits) examine the buckets with jeweler’s loupe and magnifying glass. Then comes a bearded old man to push one bucket at a time in a baby carriage to a man (bow tie, cutaway) who empties the buckets into a vat that decants into a beaker over a flame. The resultant steam condenses a drop at a time into a teacup on a turtle’s back. The turtle carries the cup to a fireman on a ladder who—pinkie extended—throws the water on the fire. The cartoon is a tour de force: eight humans, three turtles, a pump, and twelve containers—a profusion of elements yet a unity of conception and purpose.

Eight days later Dr. Seuss drew giant eyeglasses (he labeled them, helpfully, “rose colored”) for a cartoon with the title “Complacency.”208 One man asks the other: “What if we lose a bit today? We’ll snatch it back tomorrow!” The next day complacency is one barrel of “Our Big Bertha,” a cannon with six barrels.209 Four of the barrels are useless: “Carelessness,” “Red Tape,” “Complacency,” and “Blunders.” One—“Political Squabbles”—is counterproductive, blowing smoke back into Uncle Sam’s face. A side vent emits “Just Plain Gas.” Only one of the six barrels is “For Hitler + the Japs,” and it emits only a lame “Pip!”

On February 24, Dr. Seuss drew two figures buried under a huge down comforter (“Our Warm, Warm Cot”) against the icy drafts of “The Grim Cold Facts.”210 (The corner of the blanket reaches down to envelop the cat on the floor.) In April, Dr. Seuss asked: “Do YOU Belong to One of These Groups?” The three groups in question are: “The Creepers,” “The Weepers,” and “The Sleepers.”211 Among the Creepers is a man smoking a cigarette—unusual for Dr. Seuss (himself a chain-smoker); the sleepers are eight men and a cat, who have posted a sign on their bed: “Do Not Disturb Until After the War.” In a May 1942 cartoon, a happy newspaper reader reads the headline “Hitler on Skids” while leaning, blissfully unaware, against the huge snake form of “Japan,” in the act of swallowing “China.”212 The message: Things may be going all right in Europe, (though that was hardly the case); but the Pacific is another matter entirely. This cartoon is noteworthy as Dr. Seuss’s only depiction of a Chinese person. The headline “Hitler on Skids” prefigures the cartoon of October 15, 1942, which has Hitler testing the new secret weapon: skids.97 But it is not clear whether Dr. Seuss had actual headlines in mind, for Hitler suffered no major defeats in May.213 Also in May, six straw-hatted men (and a dog) at “The Optimist’s Picnic” celebrate finding a clover leaf (“A Little Good News”) even as, offshore, ten ships sink in the background.

Having drawn the devastating cartoon of “Red Tape” in February, Dr. Seuss joins Ingersoll in dreaming up in May a “Society of Red Tape Cutters” (see following page). The entire cartoon is devoted to a statement about red tape and the society—two-thirds certificate, one-third text. The text reads, in part: “The Society of Red Tape Cutters, an organization which would love to be nation-wide, today elected as its first Honorary Member the President of the U. S. A., Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt...was nominated and elected for cutting the red tape which impeded our war effort. By persistent work with the red tape shears, he has boosted production, streamlined our fighting forces, and brought closer our day of victory. Membership...is open to all public workers and officials....” The text ends: “There is no limit on the number of members; indeed, we would be delighted to elect thousands of them. So cut, boys, cut.” (In the ensuing months the Society would “elect” to membership Senator Harry S. Truman, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Russian Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and six lesser lights.)

The certificate itself is a work of art. In the center: the name of the honoree and the citation and the name of the society and “Awarded by the Readers of the Newspaper PM,” with a circular seal to one side and the signature of Ralph Ingersoll below. On the left, from the top: the legs of two men, presumably hanged by red tape; a deskworker with tape around neck and body; a pilot in an airplane, with red tape around both wings and the propeller; two men in a tank, with red tape around both necks and one gun barrel; an infantryman, with red tape around body and rifle. At the bottom: a war factory, red tape around its smokestacks. On the right: a cheerful bird greeting the sun as it comes out from behind a cloud, and giant hands holding giant scissors reaching down from behind that cloud to cut red tape and send a ship and its happy skipper off on their business. The cartoon appeared a dozen times, only the honoree changing, but it never lost its freshness.

July brought an otherworldly “Dream of a Short War,” surely one of the most magical of all Dr. Seuss’s war-time cartoons.214 Winged horse, canopied chariot, and ethereal driver come straight out of some Utopia, perhaps the Arabian Nights, but the dream is over: “End of the line, sir. From here on you walk.” One week later Dr. Seuss drew “The Alibi Boys—That Favorite Song-and-Dance Team of the Democratic Nations.”215 As two patrons look on skeptically, “We could of,” “We would of,” and “We should of” do a song-and-dance turn. Despite the placard reading “democratic nations,” this cartoon seems to focus on this democratic nation.

In the summer of 1942, Congress faced a major issue—taxes. In late July, Dr. Seuss produced a third cartoon that calls for a road map: “The Knotty Problem of Capitol Hill: Finding a Way to Raise Taxes Without Losing a Single Vote.”216 Here a bemused Uncle Sam, normal-sized, looks in through a window as top-hatted Congressmen—dwarves and a cat—attempt the impossible. One studies a model of an atom; one, standing in a trash basket, goes through the waste paper. Four work atop a table with surveyor’s instruments. One examines blueprints; one eyes an assayer’s scales. Five crowd around a sheet of paper with a lone zero in its middle. Two enter formulas in a record book decorated as well with games of tic-tac-toe. One lies supine—presumably asleep—under the table; we see only his feet.

A fourth cartoon in the same vein is “Speaking of Giant Transports...” (August 5, 1942).217 An overburdened Uncle Sam pilots the single-engine, open-cockpit plane. “Red Tape” is one of a dozen gliders he has in tow. The other drags on progress are “Talk Against Our Allies” (a phonograph going full-blast); “Peanut Politics;” “Our Ham Fishes,” that is, political critics of the administration—Hamilton Fish was a longtime Republican Congressman from New York; “The Great Rubber Puzzle” (likely a reference to the shortage of rubber once Japan severed the trade routes between Southeast Asia and the United States); “Racial Prejudice;” “6th Column Press” (a subject to which we return in a minute); and “Inflation” (again, stay tuned). In the midst of things is a man in a hammock: “Sleeper: Do not disturb until after the war.” And Dr. Seuss crammed all these elements into a cartoon measuring perhaps 6” × 7”! Note that Dr. Seuss represented “6th Column Press” with an outhouse, complete with a carved moon in the door.

In August, Dr. Seuss showed the dangers that lurk when a “defeatist” falls for Hitler’s “peace poseys.”218 “We’ll Need Changes in the Old Victory Band Before We Parade in Berlin” (August 21, 1942) shows a man with cigarette holder in his smiling mouth and tinkling away on a triangle (“Most of us doing too little”) and a much smaller man trying his best with the assistance of two hard-pressed cats to carry and blow a tuba (“Few of us going full blast”).219 In September the subject was “Our Placid Conceit”—a gentleman (vest, cutaway, and cigar) can’t accept that “We can’t win this war without sacrifice.”220 Note that it is Uncle Sam—we see only his gigantic hands—who “Can’t Pound it Into His Head!”

Unity during wartime is an obvious goal and dissent a problem. We have seen already that PM waged a campaign to silence Father Coughlin’s Social Justice, a magazine that sympathized openly with fascism abroad. But the United States was a free country, and one of its arguments with Hitler and the fascists was their suppression of dissent. In May 1942, Dr. Seuss drew a crowd of men thumbing their noses at Hitler.221 One man carries a huge banner: “So long as men can do THIS they’re FREE!” Even the bird atop the pole thumbs its nose at Hitler! Freedom includes the freedom to dissent. The original drawing carries the title “The Fifth Freedom.” In his State of the Union speech on January 6, 1941 President Roosevelt had spoken of “Four Freedoms”: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear; they became a major focus of American domestic propaganda. With this cartoon Dr. Seuss added one more freedom: the freedom to thumb one’s nose. At least in the cartoon, this freedom is strikingly white, male, middle-class, and violent—a dozen or so men carry cudgels.

How to foster unity? This was Dr. Seuss’s goal. Before Pearl Harbor Dr. Seuss rarely dealt with the issue, except—a truly major exception—in his attacks on Lindbergh and the “isolationists.” America First was the major organization dedicated to nonintervention. In one cartoon of June 1941, Dr. Seuss linked America First not only with Nazis and fascists (as we have seen him do before) but also with Communists.222 In “Relatives? Naw...Just three fellers going along for the ride!” Dr. Seuss shows a kangaroo “America First” carrying in its pouch a second kangaroo (“Nazis”), carrying in its pouch a third kangaroo (“Fascists”), carrying in its pouch a fourth kangaroo (“Communists”). It is startling for a PM cartoonist to connect Communists with the other three, since PM itself was so much a part of the Popular Front, which included Communists. But in his later manuscript about PM (archived at Boston University), Ralph Ingersoll blames unnamed Communists for the labor woes that hobbled PM virtually from the start, and we shall see that Dr. Seuss seems never to have gotten over his own suspicions of communists.

At the end of August 1941 came a cartoon showing German submariners deciding not to fire on the good ship “U. S. S. Disunity.”223 The ship carries four men, two of whom row in opposing directions and two of whom puff into the sails, again in opposing direction. Says one German to the other: “Don’t waste a torpedo, Fritz, we can take this gang with a butterfly net!”

After Pearl Harbor Dr. Seuss presses for unity.224 In February 1942 it was “That Cheap Gunning for Eleanor Roosevelt,” which leaves Hitler and “Japan” delighted. Eleanor Roosevelt was perhaps the most influential presidential spouse of the twentieth century. In a radio broadcast of a week or so earlier, she had suggested that American housewives make do with less sugar; she was astonished to find herself the target of sharp criticism, including the charge that she had encouraged hoarding. Later that month Dr. Seuss stigmatized those who didn’t pull together. The “Sniper” (February 25, 1942) depicts “Our Lifeboat” in high seas.225 It has an American flag but no captain, and an onboard sniper uses his slingshot to bean one of the men setting the pace. The assailant’s only complaint is “the color of that guy’s tie.”

As in his campaign against Social Justice, Dr. Seuss inveighed frequently against Nazi propaganda, notably in cartoons of March 1942. “Why Do We Sit and Take It?” (March 9) shows “You” and “Me” in a car at a filling station.226 The station is “Adolf’s Service—Free Air”; Hitler pumps “Anti-Roosevelt, Anti-Russian, Anti-British Propaganda” into an already-bulging tire. The next day Dr. Seuss showed the Dies Committee trapping a rabbit but missing “the Big Ones” in the “subversive activities jungle”—a huge fanged snake with a “Japanese” face, a swastika-branded beast of uncertain genus, and a rhinoceros.227 The padlock on the cage is as big as the rabbit, but that fact does not affect the pride of the committee. The “Special House Committee for the Investigation of Un-American Activities” (1938-1944) was known as the Dies Committee, after its chair. Martin Dies (D., Texas). In late February it released a report on Japanese activities. Dr. Seuss poked fun at the Dies Committee, but was the “jungle” the external world? And was Dr. Seuss opposed to witch-hunts at home? The cartoon is not clear. (In June Dr. Seuss drew a somewhat clearer cartoon [not included here]: “After him, Sam! It’s a Robin RED-Breast!” pillories the Dies Committee’s fixation on all things red. Riding a cat, swinging a lasso, and firing a toy gun, a figure labeled Dies races through the bowlegs of a bemused Uncle Sam in hot pursuit of a robin.) In March “Our Internal Wrangles” meant stripping massive gears, and again Hitler and “Japan” exult.228

We’ve seen already (in the cartoon “Speaking of Giant Transports...” August 5, 1942) that Dr. Seuss dubs part of the press a “sixth column.”217 (The phrase “sixth column,” perhaps original with Dr. Seuss, is a play on “fifth column,” a phrase that got its start during the Spanish Civil War meaning sympathizers behind enemy lines.) On April 21, 1942, Dr. Seuss drew the New York Daily News, the Chicago Tribune, and the Washington Times-Herald lying in ambush for President Roosevelt.229 The three newspapers were an interlocking family conglomerate: Eleanor Medill Patterson of the Washington Times-Herald and Joseph Patterson, owner of the New York Daily News, were sister and brother; Colonel Robert McCormick, who owned the Chicago Tribune, was their cousin. Their newspapers had the largest circulations of all American dailies, and they had been anti-Roosevelt for years. Paul Milkman refers to the News and the Hearst press as “jingoistic, xenophobic, and hysterical.” New York’s 42nd Street was home to the New York Daily News (April 30, 1942), instrument of Joseph Patterson; Milkman quotes a rival newspaper’s description of the editorial policy of the Daily News as “folksy fascism.”230

We have noted Dr. Seuss’s ambivalence toward the Soviet Union. Still, once the United States joined the shooting war and became allied with the Soviet Union, Dr. Seuss softened his criticism of Communists. A cartoon of June 4, 1942 (not included here) is one result of that change. A tiny gun (“U. S. aid to Russia”) goes to Stalin, while a huge weapon (“Justice Department anti-red blunderbuss”) is to “pepper the seat of [Stalin’s] breeches.” How contradictory to be aiding the Soviet Union and at the same time persecuting domestic Communists! But is the problem the very fact of hunts for domestic Reds? Or, is it that the hunts for domestic Reds—the difference in the size of the weapons highlights the issue—receive more support than the Soviet ally abroad? In a cartoon of June 1942, Dr. Seuss returns to the theme of the “Sixth Column” press, depicting Hitler and an American newspaperman wearing two-man shoes.231 Says the newsman: “Me? Why I’m just going my own independent American way!”

In June and July Dr. Seuss pilloried the “Congressional Sling-shot Club”—first (a cartoon of June 30, not included here) for killing a bird labeled “National Harmony,” second, for pelting Uncle Sam in a battlefield trench, from behind (July 15). Says Uncle Sam, directly to the reader: “If you expect me to win this war, Mr. Voter, keep your Katzenjammer Kids at home!” (The original Katzenjammer Kids were the pesky stars of a cartoon strip of that name.232) In “Easy, There, EASY! NO ACROBAT IS FALL-PROOF!” Uncle Sam teeters on a high wire over a vast abyss.233 An arrow hanging from the wire reads: “Victory Plenty Far Ahead.” On one end of Uncle Sam’s pole two cats engage in “Cheap Political Cat-Squabbles.” These cartoons make clear the tactical usefulness of not portraying President Roosevelt. Portray Roosevelt, and the attacks of the “Sling-shot Club” are directed at a politician; portray only Uncle Sam, and the attacks become assaults on the war effort and national unity.

Early in August, Representative Holland (D-Pennsylvania) declared on the floor of the House: “The Pattersons and their ilk must go. We want no Quislings in America.” Joseph Patterson responded two days later with a headline: “You’re a liar, Congressman Holland.” A few days later came the charge that the Chicago Tribune had printed a news dispatch that included confidential military information. (By the end of the month, an investigation cleared the Chicago Tribune.) Needless to say, these charges were music to Dr. Seuss’s ears, and he responded with “Cissy, Bertie, and Joe” (“Still Spraying Our Side With Disunity Gas,” Aug. 10).234 Cissy is Eleanor Patterson of the Washington Times-Herald; Bertie is Colonel Robert McCormick of the Chicago Tribune; Joe is Joseph Patterson of the New York Daily News. In August 1942, Dr. Seuss draws a louse labeled “The Anti-Roosevelt Bug” boasting about giving McCormick “the greatest all-time itch on record!” Note the superiority—in body size and complexity—of the “anti-Roosevelt bug” over the “just plain bugs.”235 And remember that in the forties, “bugs” was colloquial for “crazy.” In August, Dr. Seuss found the “endless cat fights on our own home front” distracting: “Gee, It’s All Very Exciting...But it Doesn’t Kill Nazi Rats.”236

Unity, dissent, and propaganda—Dr. Seuss supported the Roosevelt administration, opposed the “Sixth Column” press, and sought to unite Americans in pursuit of these goals. If he sometimes contradicted himself, so also did the Roosevelt administration. The wartime economy affected everyone, whether in the form of shortages, inflation, or inequity. The war brought economic prosperity to the United States, but in the long run, not in the two years Dr. Seuss was drawing his cartoons. He focused instead on ways the war effort affected folks in the short run: war taxes, shortages of goods, problems of production, inflation, malingering. Perhaps better than other, more objective indicators, his cartoons tell us how the war affected many lives at home.

In August 1941, before Pearl Harbor and before the U. S. involvement in the war, Dr. Seuss drew two wealthy club men lamenting new taxes: “And with new WAR Taxes, mind you, we’ll soon be going THREES on our dollar cigars.”237 A cartoon of November 18, 1941, “Blitz Buggy De Luxe,” shows “Uncle Sam” driving a tank.238 He has cigar in one hand, martini in the other; behind him stands a butler before a table set with linen and candelabra, and a bottle of champagne chills in a bucket on the floor. The subtitle: “Destroy Hitler (IN PERFECT COMFORT).” And this is before Pearl Harbor!

Soon after Pearl Harbor, on December 26, 1941, Dr. Seuss urged his readers to buy war bonds.239 A man at home reads somber headlines: “Japs Sink U. S. Ships.” A moose head mounted on the wall leans down and speaks: “Boss, maybe you’d better hock me and buy more U. S. Defense Bonds and Stamps!” Even before Pearl Harbor the Treasury financed the defense buildup in part with “Defense Bonds.” Once the United States entered the war, “Defense Bonds” became “War Bonds,” to be bought at one’s place of work by authorizing deductions from paychecks. In January 1942, Dr Seuss pushed this payroll savings plan: “If you’re not in it, ask your boss!” That same month Dr. Seuss made light of tightened belts in a hilarious cartoon (January 12, 1942).240 241 It shows a hefty matron clad in fur coat confronting the rubber shortage. She wishes to buy a girdle, and the only one available is far too small. The solution awaits her in the fitting room: two store clerks ready with outsize tongs and crane-like apparatus with huge hook. “The Old Easy Life” (January 19, 1942; not included here) had to go: Uncle Sam as boxer with one boxing glove already on has to choose for his second hand between manicure (“The Old Easy Life”) and a second boxing glove.242 Dr. Seuss wanted “PRODUCTION PRODUCTION PRODUCTION PRODUCTION” (March 4, 1942), and he transformed the smokestacks of factories into blowtorches scorching the posteriors of Hitler and “Japan.”

Dr. Seuss attacked slackers (March 6, 1942): “Too blamed many of us” have not speeded up, and victory is still “Miles + Miles + Miles ahead.”243 In a cartoon of March 20, 1942, “You Can’t Build a Substantial V Out of Turtles!”, it is “Dawdling Producers” who are turtles.244 Almost all the turtles look happy or at least complacent, but Dr. Seuss clearly was not. This V of turtles prefigures the much higher tower of turtles that after the war leads to the downfall of Yertle, king of the turtles, in Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories (1958).245 On April 8, 1942, Dr. Seuss drew a happy umbrella salesman ringing up his profits as he sells umbrellas to people stranded in a flood. A swastika in the storm identifies the cause of the flood. The caption: “Beware the Man Who Makes a Fortune in a Flood!” Later that month (April 29, 1942), Dr. Seuss drew a cartoon with a similar theme. A lifeboat (“U. S. life-boat”) is already crowded.246 It holds eighteen people, including six sailors doing the rowing, six men passengers, one woman, and five children. Their dilemma: whether to rescue a businessman in a life jacket, complete with cigar and huge cash register labeled “High net incomes + profits.” Says one sailor to the group already in the boat: “He thinks we oughta save his cash register, too!”

In May, Dr. Seuss criticized New Yorkers—and by extension all Americans—for not maintaining blackout and hence aiding Nazi submarines.247 The Nazi submarine has already released a torpedo toward a freighter it has spotted against the lights of “N. Y. City.” In June, he attacked slackers in the workforce: “YOU + ME” is the label on the hat of the complacent fellow in a hospital bed, phoning in to take sick leave.248 On the wall above his head a “Home Front Health Chart” traces a downward trajectory. In late June, Dr. Seuss drew “Phony Optimism.” A man and woman with fatuous smiles on their faces stroll along holding eleven balloons, while in the lower left corner one cat remarks to another: “A balloon barrage...but not against bombs.249 It’s designed to protect the mind against facts!” (Barrage balloons were tethered by cable around likely targets as a defense against low-flying enemy aircraft.) In July, Dr. Seuss attacked inflation: a worried Uncle Sam reads a child-care book (“How to Bubble the Baby”) as he seeks to restrain a baby whose huge belly—‘Inflation’—makes him float to the ceiling.250 Even the cat pitches in.

In August, Dr. Seuss connected the shortage of goods and the shortage of effort. Wearing a chef’s hat and standing over a stove, Uncle Sam laments, “If we had some ham, we could have a Real Production Omelette right now...if we had some eggs...” and his sidekick cat, pointing to “effort shortage” in the firebox, adds, “...if we had a bigger fire.”251 252 Two days later, Dr. Seuss ridiculed those who talked but didn’t act, in this case, to collect the scrap metal the war effort needed. Says the puzzled cat on the backyard scrap heap: “But nobody wants to attack the scrap right in his own back yard!” In September (a cartoon not included here) a “war materials bootlegger” wears a decoration around his neck. On the decoration is a dollar sign. The bootlegger speaks or sings: “Oh, the lowly private swims/Through pools of blood and loses limbs/Just to get a D.S.O. hung round his collar./But, hell, why die for tin/When it’s easier to win/The Exalted Order of the Stinking Dollar!” (D.S.O. stands for Distinguished Service Order.253) Three days later Dr. Seuss responded to Congressional talk of price and wage ceilings with one of his most startling cartoons: floor has become ceiling and ceiling, floor. (The door hasn’t changed!) In October, Dr. Seuss illustrated the scrap drives that became a feature of wartime life: a truckload of scrap metal—radiator, bedstead, boiler, gear, bathtub, bike, rake, clock, trumpet, and assorted pots and pans—with a matronly lady riding on top.254 The zipper of her dress extends down the front of her dress from neck to hem, and she offers it as scrap—but only if the government can get it unzipped!

Just before Christmas, three enchanting reindeer addressed the reader: “Maybe it’s none of our business...but How much are YOU giving This Christmas in U. S. War Bonds and Stamps?” The next day, December 23, Dr. Seuss urged his readers not to travel at Christmas.255 256 The crowd charging “Track 25” is one of Dr. Seuss’s great crowd scenes: a swirling scrimmage of men (and a few women) who carry gift boxes large and super-large and even a Christmas tree with all its decorations. Hats, gift-wrapped parcels, and three men fly; men stand on each other’s backs and step on each other’s heads. Three men in the lower right have given up the fight. Shortly after Christmas (December 28, 1942), Dr. Seuss drew a most repulsive hoarder–alone in his well-stocked warehouse, with huge cigar and enormous stomach.257 Dr. Seuss’s penultimate cartoon, in January 1943, is dated 1973, thirty years after “the Battle of 1943.”258 A bearded veteran with cane boasts to his grandson of having “groused about the annoying shortage of fuel oil!” A skeptical cat looks on.