In previous chapters, you learned why we struggle in the stock market, how to nudge performance by automatically buying low and selling high, that 3 percent per quarter is the best signal line showing us to buy or sell, and that small-cap stock and bond indexes are the ideal investments to use in the plan. Next, we’re going to get a handle on cash management.

No matter where you run your 3 percent signal plan, you’re likely to contribute more cash periodically to your bond fund. In an individual retirement account, you’ll probably contribute on a monthly basis. In an employer retirement account, cash usually flows in from every paycheck. In a nonretirement brokerage account, you might set up a regular cash transfer schedule from your bank and send extra cash whenever you’re lucky enough to find some.

If the market rises over a long enough period without many setbacks causing 3Sig to buy, your selling proceeds and cash contributions could combine to grow your bond balance until it’s too big relative to your stock balance. You want most of your money to work for you by rising with the stock market over time, so an unduly large bond balance should be avoided. Then again, the stock market occasionally plunges so deeply that what looked like an oversize bond balance can suddenly come in handy for buying the lower lows. You need to strike a balance, so to speak.

In this chapter, we’ll look at how to invest a large cash balance gradually, techniques for managing your plan’s bond balance, the usefulness of a bottom-buying account, and how to adjust your bond balance as you grow older and more risk averse.

Starting with a Large Cash Balance

Managing a large cash balance is tricky. The last thing you want to do is plow it all into the stock market at a key top and watch a third of it evaporate in the months ahead, but you probably also know that you should put the money to work earning more than a low interest rate.

Historically, it’s been better to put large sums into the market straightaway, but we are emotional creatures and remember the exact wrong moments for doing so from past news cycles. The magazine covers in the wake of 1987’s Black Monday, the talking-head panic during the 1997 Asian Contagion, the I-told-you-so lectures from z-vals in the dot-com crash of 2000, the constant updating of how much wealth was lost during the subprime mortgage collapse of 2008—these and the stress of other financial calamities are seared into our collective consciousness, and we are determined to avoid such money pain if at all possible. Even though the odds of right now being a perfectly wrong moment for investing a large sum of cash are low, your mind tells you that it might be. Thus, cash tends to waste away on the sidelines and miss out on market performance.

To get around this, I suggest breaking up a large cash balance into four equal sizes that you’ll invest in 3Sig across the next four buy orders. They won’t necessarily happen back to back, so the four quarterly buy signals might span a few years. Whenever they happen, though, you’ll add to the signaled order size the extra amount of cash you want to invest. This also works well for transitioning your existing portfolio balance to 3Sig, in which case you would sell a quarter of it with each buy signal, then add the proceeds to your buy order.

For example, if you’re dividing $100,000 into four equal amounts that you want to put into the plan, you would add $25,000 to each of the next four buy signals. If the plan signals a buy with $3,000 at the end of next quarter based on your current invested balance, you would add $25,000 to it, for a total of $28,000 invested. If the fund you’re using closed the quarter at a price of, say, $88, you would buy 318 shares with $28,000, instead of the 34 shares the plan signaled you to buy with $3,000. After your additional funds go into the plan, it would then calculate the next quarter’s 3 percent signal line from the larger investment balance.

After four quarterly buys in this manner, your large cash balance will be working in the plan. If the market goes through rough patches while you’re gradually moving your cash balance into it, you can feel good about buying in at lower prices. If it just keeps marching higher before you get all your cash into it, you can feel good that you already moved a portion of your cash in. I’m a big fan of gradual moves as a way of mollifying disappointment in the uncertain environment of stocks.

Purists may scoff at this approach, and would probably cite statistics showing that stocks rise much more often than they fall. What they perpetually ignore is that people are not dispassionate machines making rational choices at every turn. Emotions figure in, in a big way, and moving gradually provides a good compromise between head and heart. It puts your large cash balance to work in a manner that you can comfortably watch happen.

Your Living, Breathing Bond Balance

Both the stock side and the bond side of 3Sig fluctuate in value. The stock side is affected by the market’s daily gyrations and by your quarterly buys and sells. The bond side is affected by your deposits, possible occasional withdrawals, and the same quarterly buys and sells that affect the stock side. It may come as a surprise, but you’re actually more involved with the bond side than the stock side. It’s part of every quarterly trade and is the only side you’ll interact with between trades, usually by depositing more cash. All new cash to the plan goes into your bond fund first, and is later incorporated into the stock fund through a quarterly growth target adjustment you’ll learn about in the next section.

Due to this activity, your bond balance will vary from month to month and quarter to quarter. Like a lung breathing air in and out, your bond fund will breath money in and out. Also like a lung, this is its normal function. There’s no reason for alarm as it moves from inhaling money and becoming bigger, to exhaling it and becoming smaller. Again, like a lung, however, it should stay neither too big nor too small for long.

Most of the examples in this book begin with an 80/20 mixture of stocks to bonds, and it’s a good ratio to keep in mind. It provides enough buying power in the bond account to handle a big setback in the market, but keeps the bulk of your capital growing with the market’s upward tendency over time. A 5/95 stock-to-bond mix, or a 25/75 mix, or a 50/50 mix, would leave you missing out on too many gains; while a 95/5 mix would leave you without enough bond balance to buy many of the market’s downturns. Somewhere between these extremes is where you want your balance, and 80/20 does nicely in most environments—not all environments, as you know by now, but most. We’ll consider the 80/20 stock/bond ratio to be our base mixture, back to which we want to rebalance periodically, at opportune times flagged by 3Sig.

If you’re like most people, you’ll run the 3 percent plan in a retirement account. Once you see how well it works, you’ll probably end up using it in your nonretirement accounts, too, but we’ll discuss cash management here as it relates to your retirement account. The natural direction for the bond side of your retirement is up, due to regular contributions. The stock/bond interaction will stay fairly balanced over time, with occasional deviations from the mean when the market enters prolonged bull and bear phases, but even these are eventually corrected with a reversion to the mean that resets the plan back toward its 80/20 base. Now and then, however, you’ll need to intervene to get it back there more quickly.

There are two techniques you’ll use to keep your growing retirement bond balance flowing into the stock side of your 3 percent signal plan. Left alone, the plan will issue signals that keep only the initially invested stock balance growing at 3 percent per month. If you don’t adjust something as your bond balance grows, the plan’s trading signals will steadily become smaller and smaller relative to your overall account balance, and leave too much of your capital uninvolved in the system. We can’t have that, so we turn now to the two ways of drawing fresh cash into the plan and keeping the plan’s mixture of stocks to bonds correct.

The Modified Growth Target

Remember, all new cash into your plan goes first into the bond fund. You do not divide contributions between the stock and bond funds as you make them. Instead, you’ll adjust your quarterly stock fund growth target to incorporate half of the new cash that flowed into your bond fund during the quarter. With 3Sig, every dime of new cash lands initially in your bond fund.

The first way of involving this new cash in the plan is to adjust your quarterly signals higher to account for the growing bond balance. This works best in cases where the pace of new cash contributions to your bond fund is constant, such as 6 percent of pay plus a 50 percent employer match for a total of 9 percent of your salary. If you make $6,000 per month and are paid every two weeks, then 9 percent will become a rate of $270 every other week, or $540 per month. That’s $6,480 per year into your retirement bond fund. If you began the plan with a $10,000 balance in your retirement account, the $6,480 per year in new deposits would represent 65 percent of your starting balance in just the first year. This high rate of new cash flow into the plan needs to be incorporated into the system.

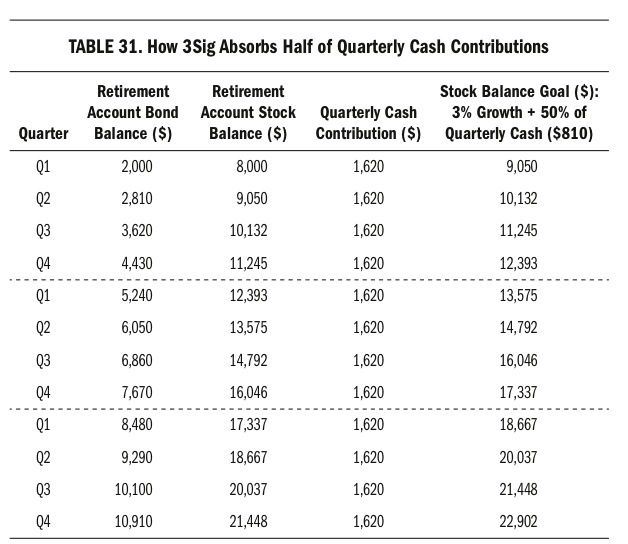

The $540 per month in this example is $1,620 per quarter. In the first quarter of the plan, the 3 percent growth target on $8,000 invested (the 80 percent stock allocation of your $10,000 total starting balance) is a quarterly gain of only $240 to $8,240. Your new cash contribution is nearly seven times greater than the plan’s growth goal for the quarter. To incorporate all that cash, you’d need a growth target of not 3 percent, but 23 percent! That’s $8,000 plus $240 to reach the 3 percent signal line and $1,620 from you, for a total of $9,860.

Remember, though, that we’re striving for an 80/20 stock/bond mixture, so you should not move all your cash contribution into stocks every quarter. Some of your new cash should end up in the market, but some should stay in bonds to help with future buying opportunities. Should we divide new cash along the same 80/20 mixture as our overall portfolio, so that 80 percent is earmarked for the stock side and 20 percent remains in bonds? You would think so, but in fact it’s better to divide new contributions right down the middle, allocating half to the stock fund growth target while keeping half in bonds.

This is because the stock market tends to rise, and our 3 percent target on the stock side naturally pulls the stock fund balance higher. To help the bond fund stay near its 20 percent base allocation, it’s best to leave half of new contributions in it. Easy enough. Divide your quarterly contribution to the bond fund in half, making $1,620 into $810 in this case, and build the $810 into your growth target. In the first quarter of the plan (when you started with $8,000 on the stock side of your account), the quarterly balance goal would have been $9,050 after your new cash was built in. Here’s the formula that tells us so:

stock balance ($8,000) + 3% growth ($240) + 50% new cash ($810) = goal ($9,050)

It would take 13 percent growth in the quarter to achieve your modified goal. This almost never happens, so in the beginning of your plan, when the balances are low, you’ll need to buy more shares of the stock side almost every quarter. This is no problem, because you already supplied your bond fund with the buying power needed for the additional growth target. The “50% new cash” portion of the formula is based on your quarterly contribution, after all, which is in the account and ready to buy. For most people, the situation wouldn’t be this extreme, either. First, few people earn $6,000 per month when first starting their retirement plan. Second, by the time they do earn $6,000 per month, their retirement plan balance is high enough that monthly contributions don’t introduce such a big distortion.

A big distortion is a good predicament, though, because it means you’re directing a lot of fresh cash into the plan. This is a problem most of us would welcome. If you find yourself facing it, keep quiet. Nobody likes to hear a person moaning at the Christmas party about the hardship of managing copious amounts of cash gushing into their retirement account. Besides, if you keep working the cash into the plan using this method, it won’t take long until your retirement balance has grown enough to bring the new cash flow down to a more modest relative size.

Let’s take this example through a few years, assuming your salary stays constant in the time frame. We’ll see how the plan would progress with 50 percent ($810) of each quarterly cash contribution ($1,620) staying in the bond fund balance, while 50 percent ($810) goes into the stock balance at the end of each quarter, with the stock balance growing at exactly 3 percent per quarter so there are no trades triggered by 3Sig. You won’t go three years without a buy or sell signal in real life, but we’ll assume it here just to illustrate how the plan absorbs new cash:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1uDrmyz) for a larger version of this table.

At the end of the three years, your bond account balance of $10,910 is 34 percent of your total retirement account balance of $32,358. Don’t be confused by the $22,902 in the last column of the last row, which is your stock balance goal for the quarter. At the beginning of the quarter, your bond balance plus your stock balance came to a total balance of $32,358. Divide the bond balance of $10,910 by the total balance to get 0.34 or 34 percent.

At the end of this three years, our base mixture of 80/20 stocks/bonds had become 66/34—pretty far off. The reason the mixture departed from our base is that the stock balance grew at only 3 percent per quarter on top of the new cash contribution while the bond balance received just as much new cash as the stock side. Since bonds began at only $2,000 and stocks at $8,000, the half of each quarterly contribution left in bonds made that side grow disproportionally more than the stock side. In the first Q2, for instance, $810 represented 41 percent of the previous quarter’s bond balance, but only 10 percent of the previous quarter’s stock balance. Of course, bonds as a percentage of the total grew more quickly on an equal share of the quarterly contribution.

In real life, the market will be fluctuating and won’t return precisely 3 percent in a quarter. You’ll be buying and selling along the way. The buying will use up your bond allocation, so it won’t just grow continually as a percentage of the total. The selling will add to your bond fund, growing it more. You might think we should tweak our cash contribution so that slightly more goes into the stock side and slightly less remains on the bond side to prevent the 80/20 base mixture from getting out of whack, but it’s not worth it given the ebb and flow of the zero-validity environment. We can’t know in advance which imbalance the market will produce, or when.

Luckily, imbalances are no problem for us. Now that you know how to incorporate new cash into the plan, it’s time to see how to handle departures from the 80/20 base mixture.

The Adjusted Order Size

Most fluctuation around the 80/20 stock/bond mixture is fine. It might move to 75/25, then to 85/15, and back again in most environments. Every once in a while, though, it will get outside a reasonable fluctuation zone and need your intervention to regain its base 80/20 posture.

The reasonable fluctuation zone is anywhere between 70/30 and 90/10. This is subject to interpretation, but the twenty-point range is a good one for giving the market room to wiggle. After each quarter’s action, divide your bond balance by your total balance to see the bond balance percentage. If it’s lower than 10 percent, it’s a good idea to add cash, as we’ll discuss later. If it’s higher than 30 percent, it’s a good idea to adjust an upcoming signal order size to rebalance back to the 20 percent base level.

For instance, if your bond balance is $10,000 and your total balance is $50,000, your bond percentage is exactly 20 percent and your stock balance exactly 80 percent of the total—spot on. If the balance later becomes $15,000 bonds and $70,000 total, your bond percentage is 21 percent. If it becomes $20,000 bonds and $80,000 total, your bond percentage is 25 percent. If it becomes $30,000 bonds and $90,000 total, your bond percentage is 33 percent. At this point, you have too much money in bonds and need to get more into the stock market. To do so, you would wait for a buy signal then increase its size to put more of your ample bond balance to work on the stock side. How much more? Let’s have a look.

Putting Excess Cash to Work

If you’re like most people taking a casual glance at this plan, you would assume that the bigger the buy signal, the more additional money you want to use. The reason is that a bigger buy signal indicates a better bargain in the market. We want our stock fund to go up 3 percent in a quarter. If it goes up only 2 percent, that’s a slight bargain for a purchase. If it goes up 1 percent, that’s a better bargain. If it falls 5 percent, that’s an even better bargain. Hence, the bigger the buy signal, the better the bargain and thus the better the time to put more of your money to work.

With this idea in mind, I structured the original version of this plan around an elegant system of deploying extra bond balance by increasing buy orders by 10 percent for every rounded percentage point below the 3 percent signal in the market’s quarterly shortfall. If the market gained only 2 percent in a quarter, that’s 1 percentage point less than the 3 percent growth target, so you would have increased your order size by 10 percent. This progression ramped up your strategic deployment of excess bond balance as the market bargain increased, which seems to be just what you want. You would keep this plan in place until your account’s bond balance came back down to 20 percent, at which time you would resume the standard 3 percent signal order size.

As clever as this approach seemed to be, I discovered later that it’s unnecessarily complicated. In fact, the plan works better when you wait for bonds to reach the 30 percent line, then use the next buy signal to move all the excess down to the 20 percent line into stocks—regardless of the size of the buy signal. This is counterintuitive but true, and harkens back to the trade-off between bond and stock allocations that we looked at in the “Beating Dollar-Cost Averaging” section of Chapter 4.

The reason it’s better to move your excess bond balance in all at once on a buy order rather than fine-tuning order size is that the market doesn’t deliver deep drops frequently enough to draw in large bond balances quickly. They end up lingering over several cycles. Since the market’s tendency is to rise, putting extra cash in at the first opportunity works better in most environments. Notice that you will use only enough extra bond balance to bring your allocation down to the 20 percent base level. This, combined with letting excess bond balance accumulate up to 30 percent of your account, guards against depleting bonds to an amount so small that you can’t fund future quarterly buy signals.

Don’t think you won’t need it. People naturally expect market movement in one direction to be followed by movement in the other, a tendency sometimes described as the rubber band snapping back. If stocks go down 8 percent this quarter, the thinking goes that the rubber band is stretched too far in the down direction and is tensed for a snapback in the up direction. The farther stocks go down, the more extreme the stretch, so the better the eventual snapback should be, right? Yes, but the key is eventual, and you know by now that not a soul on earth can tell you when eventually begins. A quick jaunt through recent market history is all it takes to illustrate this point.

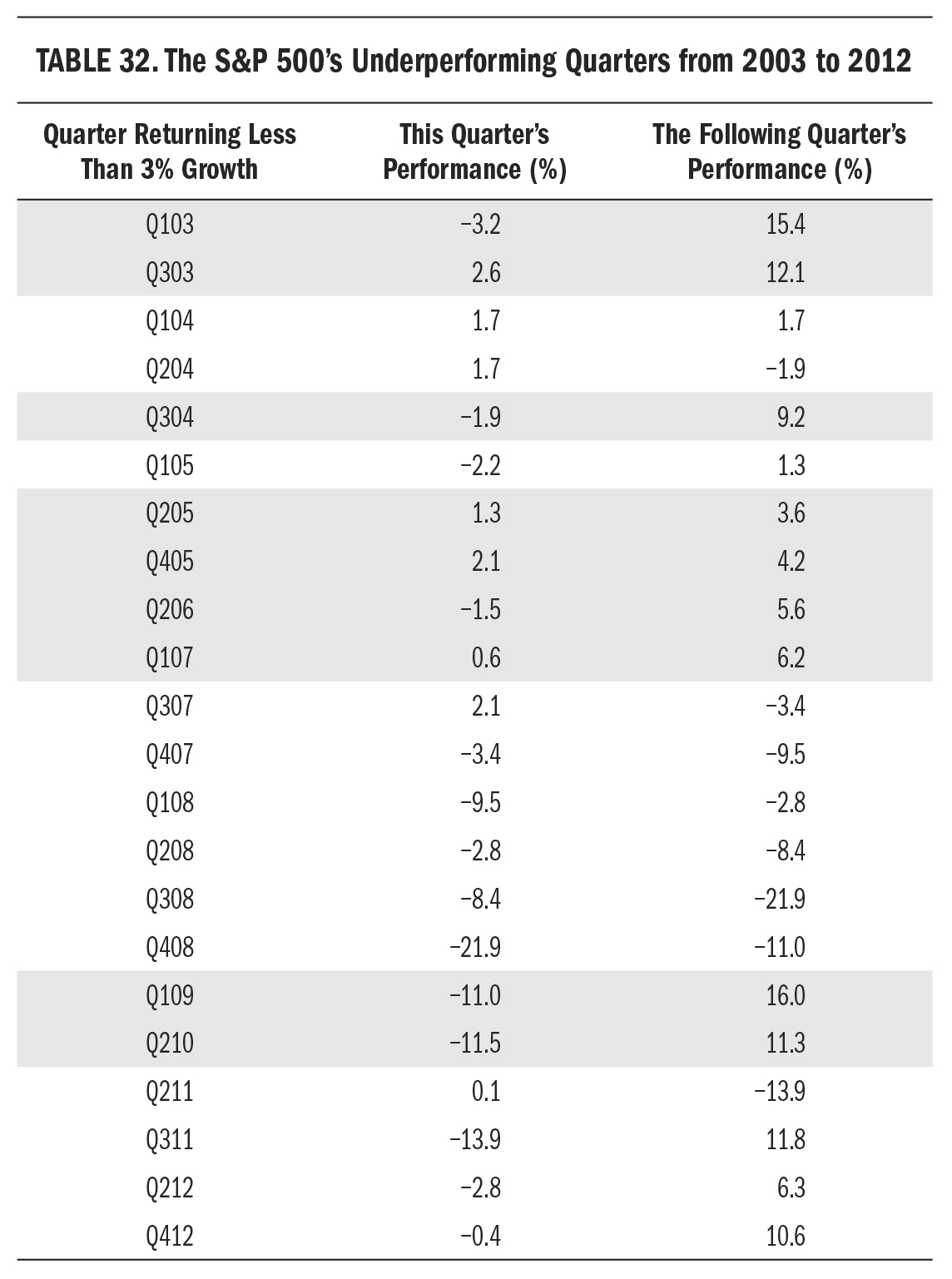

The following is a table of quarters from 2003 through 2012 that returned less than 3 percent in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund, which tracks the S&P 500. There were twenty-two such quarters, of which only nine were followed by quarters returning more than 3 percent while the remaining thirteen underperforming quarters were followed by another underperforming quarter. The thirteen of twenty-two quarters comprise 59 percent of the time. Well over half the quarters signaling to buy into the stock side of your portfolio were followed by at least one more quarter issuing another buy signal. The table highlights the nine losing quarters that were followed by winning quarters. Note that the sequence down the left column does not always list back-to-back quarters:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1upIkuF) for a larger version of this table.

The table shows why you shouldn’t get greedy and use a current buy signal to plow your whole bond balance into stocks. A drop this quarter might be a one-off, as in Q304, but it might be the starting gun for a new trend, as in Q407. If you’d moved all of your bond balance into stocks in Q407, you would have been unable to take advantage of the much cheaper prices to come in the five quarters ahead. That was such an unusually bad phase that almost every way of managing bond balance into the downturn ran the bond fund dry and needed extra cash from outside the plan, but pacing buy orders by following 3Sig and the guidelines just given for deploying excess bond balance would have prolonged the plan’s internal purchasing power. It will do well enough in most cases that a regularly funded account, such as your retirement, will not run dry.

Even in unusually awful times, though, this modified order approach is pretty good, because you’ll prevent it from magnifying buy orders beyond returning an excessive bond balance to its 20 percent range. Once you get bonds back to 20 percent, you’ll return to standard order sizes.

Eliminating a Cash Shortage

So far we’ve discussed what to do in the joyful case of finding yourself with too much cash in your bond fund. What about the less joyful case of finding yourself with too little cash there?

The same way the market’s tendency to rise led us to skip adjusting orders in the last section and move all excess bond balance in at the first buy signal, so it leads us to avoid selling extra stock shares beyond the plan’s signal. The stock market’s upward bias means that all of our rebalancing efforts should focus on keeping as much of our money at work as possible while retaining a reasonable amount of buying power for downturns. We’re defining that reasonable amount as the base 20 percent bond allocation, and rebalancing back to it once it hits 30 percent on the upside. On the downside, we’ll use a 10 percent bond balance as a signal that we’re starting to run dangerously low, and should add more cash.

More cash isn’t always available, in which case you should purse your lips and wait for a market recovery to replenish the bond side of your account by selling some of your stock fund into strength. The market will often recover in time to prevent your bond fund from bottoming out—but not always. The plan’s bond balance will sometimes go to zero, as it did in the subprime mortgage crash. If there’s no outside reserve to draw upon, you’ll have no choice but to skip buy signals until your empty bond fund is recharged to a bigger allocation by regular cash contributions and sell signals.

You may need to get comfortable, as it can take several quarters or years for the market to restore your account’s base mixture, which is fine. The worst that happens is that you stay at or near zero bond balance for an extended period during which you become a garden-variety buy-and-hold investor. Like anybody holding through the downdraft, you’ll sit tight for the eventual recovery. True, you won’t take advantage of the recovery by putting more cash to work at lower prices, but nor will you puke at the bottom and sell at the worst possible time, like so many z-val adherents. You’ll just wait. When the worm turns and stocks rise for a while, ensuing sell signals will raise cash that goes into your bond fund.

The best course of action to take when your plan runs low on bond balance is to deposit more cash. There’s just no way around it. This keeps the plan working as intended, enabling you to take advantage of strong buy signals. You run out of bond balance only when the market has been falling for an extended period or deeply in a short period. In each case, it’s exactly the right time to buy as the z-vals get depressed and gnash their teeth publicly about everything wrong with stocks. “Fascinating,” you’ll mumble as you reach for the BUY button. You can behave this way only if you have buying power in your bond fund.

There’s one rare exception to this basic truth, which we’ll cover next.

Keep a Bottom-Buying Account

Most of the time your plan will have enough bond balance to fund buy orders, thanks to your regular cash contributions and sell orders issued by 3Sig after strong stock market quarters. For the rare cases when you run out, however, there’s another layer of safety you should put in place: a “bottom-buying” account. It’s where you should accumulate extra cash for the express purpose of being able to reach for the BUY button when all about you are panicking to sell on the error-prone advice of z-val commentators.

You’re contributing to your account’s bond fund regularly, earmarking half the contributions for the stock fund’s growth target and retaining the other half in the bond fund. Because of this, and because the stock market rises more often than it falls, your most common challenge will be deploying excess balance from your bond fund, not suffering too little. Every once in a while, however, the black knight makes his move and the market crashes big time. Given a little extra cash in such an event, you can make the crash work for you rather than against. You already possess the tool that tells you when you’re facing such a moment, 3Sig. Now you need to be sure you have the firepower to take advantage of it.

You can take your time funding the bottom-buying account because you’ll almost never need it. In Chapter 7, you’ll meet a fictional investor named Mark who ran 3Sig in his company retirement account over the fifty quarters we’ve been looking at from December 2000 to June 2013, during which time he made typical contributions as his income grew from $54,000 to $81,000 per year. Only three of the fifty quarters demanded more money from Mark, and this was a time frame containing one of the worst stock market dives in history. Put differently, the plan’s sell signals and Mark’s contributions funded 3Sig 94 percent of the time and needed outside help only 6 percent of the time. An all-clear rate of 94 percent is comforting. It suggests you’ll have plenty of time to squirrel away a few nuts in your bottom-buying account so that even rare stock market swoons work for you rather than against.

You don’t have to put money in it every month or every quarter, but whenever you come across a little extra and can resist recarpeting the den or whitening every tooth in the family, pad the bottom-buying account. These sporadic deposits add up. If you can manage a regular contribution, so much the better. The savings can serve double duty as a rainy day fund and a bottom-buying account.

Some good funding sources to consider are part of periodic bonuses you might receive from your company, part of occasional profit surges from your business, gifts, tax refunds, property sales, and so on. Such nonregular sources of income are good candidates to supply your bottom-buying account, which can be any type of safe fund at a brokerage firm or bank.

Another good option is to redirect a percentage of increased income to the account. You’ll probably apportion growing income to other goals, anyway (including your retirement account, of course), and you could make it a natural part of the procedure to add your bottom-buying account to the list of items needing to be funded. Maybe you give it 5 percent of income growth or something similarly modest. Almost all the time, the bottom-buying fund just sits there doing nothing but reassuring you that there’s even more cash tucked away somewhere in the event of an emergency, whether of the stock market or the regular life variety. I’m a big fan of hidden cash pools.

How Much to Set Aside

How much should be in the bottom-buying account? Whatever you can manage, but I like the simplicity of making it a second 20 percent. You’re already maintaining a 20 percent bond balance in 3Sig, rebalancing down to it when the balance gets too big and adding to it when it gets too small. Seeing that you also have a bottom-buying balance of the same size is an easy goal to keep in mind.

Admittedly, it’s not simple putting it together, because the sums involved can be large. Then again, there’s plenty of time, and in the beginning the balances will be more manageable. In our example of starting with $8,000 in stocks and $2,000 in bonds, your fully funded bottom-buying account would hold another $2,000. Over time, you’ll grow your retirement account to a balance of $20,000 with $4,000 in bonds, and your fully funded bottom-buying account would hold another $4,000. On it goes at a pace that’s not impossible to picture.

For example, 3Sig begun with $8,000 in stocks and $2,000 in bonds at the end of 2000, receiving a $300 quarterly contribution, reached $20,000 in the fourth quarter of 2003 and $30,000 in the first quarter of 2006. That was three years during which to add another $2,000 to the bottom-buying fund so it matched the bond fund’s $4,000 target balance, then another two years for the next $2,000. When the subprime mortgage crash exhausted your 3 percent signal plan’s bond balance in the fourth quarter of 2008 and left it unable to buy the big drops of the next two quarters, you probably would have added another $1,000 to your bottom-buying fund during the intervening two years, for a total of $7,000 ready to go. That would have covered 80 percent of what the plan needed during the fourth quarter of 2008, which isn’t bad. What were most people doing then? Selling as fast their fingers could click.

Keep in mind that the buy signals of those two quarters were among the most extreme ever issued by the plan, as they were among the worst quarterly drops in market history. IJR fell 26 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008, and 17 percent in the first quarter of 2009. Being able to handle half those buying signals is pretty good. Needing to do so is pretty rare.

Thus, while it’s not easy to create an additional “just in case” fund of extra cash, it’s doable and could be well worth it. Besides, what’s the risk? That you have extra cash in the event of an emergency? Nothing wrong with that, even beyond the slim chance that 3Sig will one day tap you on the shoulder and whisper, “Time to buy the bottom.” In the case of the subprime slide, you would have been glad you did. By the end of 2009, shares of IJR bought on the plan’s fourth quarter of 2008 signal had gained 26 percent, while those bought on its first quarter of 2009 signal had gained 52 percent. Bottom-buying, indeed.

If the market ever goes so far south that your 3 percent plan exhausts its bond balance and everything in your bottom-buying account, and then whatever else you can scrape together, but the plan is still signaling for you to buy more, you’ve reached the maximum danger point.

This is not for the reason you might expect. It’s not the point of maximum danger because the market is going to vaporize your lifetime savings. Quite the opposite. It’s the point at which you’re most vulnerable to doing precisely the wrong thing, bailing at the bottom. Because you’ve thrown everything you have at your account to no avail, it seems that the wheels are coming off the cart and the stock market will never, ever recover.

This is the dilemma facing buy-and-holders and dollar-cost averagers, too, as you read earlier. Avoiding it in almost all circumstances, even as we seek higher returns through concentrated investing in small-cap stocks with a proven formula, is why 3Sig is better. However, no matter how well you prepare, it’s possible for stocks to derail badly enough to wreck your buying power. If you ever enter a downturn with at least 20 percent of your 3 percent signal plan in bonds, and have a good-size bottom-buying account set up, and the market still burns through it all, you’re dealing with one seriously Godzilla-size belly flop. You know what, though? They’re out there. All we can say about the biggest ones we’ve seen—and we’ve seen some real doozies—is that they’re the biggest so far. Give the banksters and the politicos a few more goes at it, and they’ll surely unleash even bigger ones someday.

If and when you’re in the teeth of the thing, shaken and bashed to the price floor, out of money, trying to find my phone number so you can call me up and say, “Thanks a lot, pal. This isn’t quite going the way you said it would,” turn to the signal. What is it telling you? To buy. You can’t buy, so what’s the next best thing to do? Hold. In this moment, you’re doing nothing better than any buy-and-hold investor except that you have an advantage they don’t, which is the signal. You might not be able to buy while it’s flashing, but you know that it’s going to be right eventually and the reason it’s going to be right is that today’s low prices will become higher prices tomorrow. Even when you can’t follow the signal, it will give you the confidence you need to stand pat for the recovery.

Emotional preparation is the key to navigating some of life’s hardships, and this is one of them. If you know that your second-guessing engine is going to hit overdrive at this maximum danger point of exhausting your cash, you won’t be surprised when it does. “I was aware of this possibility,” you’ll be able to tell yourself. “I knew it could happen to me, and now that it has, I’m just experiencing the predictable emotion of wanting to escape the pain. I know that’s the wrong move, though. I know the market will recover. I know that I should tune out the news and focus on the proven signal, which is telling me to buy, but I’ll just hold since I’m out of cash. I know this is the maximum danger point, because if I blow it here, if I bail at the bottom, I could give up many years of progress in one emotional and irrational move.”

If you’re adequately prepared cash-wise, this will either never happen or happen very rarely, but we can’t rule it out. If and when it does happen to you, gird your loins, watch that signal, and keep your money fully invested in the small-cap index. It will pay off eventually. If it’s any comfort, know that my money will be right there along with yours, marking time until the recovery.

Adjusting Your Bond Balance as You Grow Older

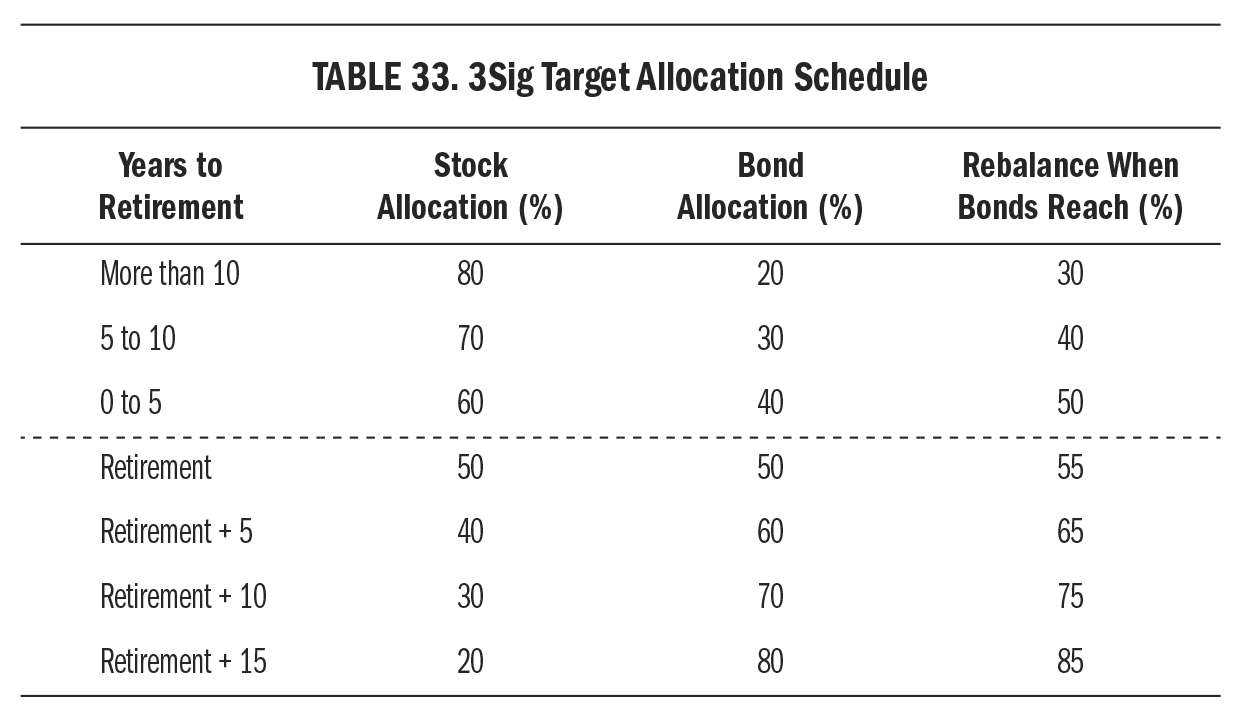

For most of your working years, the base 80/20 ratio of stocks to bonds will serve you well. As you grow older, however, you’ll want to adjust the proportion of stocks lower and bonds higher to build more safety into the mix. The plan makes it easy to do so, and you still need only the two funds. We don’t want to leave anything to chance or judgment, so here’s my recommended schedule for adjusting the base ratio, along with the level from which you should rebalance back down to the target bond allocation, as you read about in “Putting Excess Cash to Work,” earlier in this chapter:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1y9d2s8) for a larger version of this table.

This is overly simplistic to a lot of financial planners, who would prefer showing you exhaustive studies of decimalized breakdowns, as if the precision in the numbers made life less unpredictable. I once saw a recommendation for a fifty-year-old to put 41 percent in U.S. stocks, 17 percent in international stocks, 33 percent in U.S. bonds, 8 percent in international bonds, and 1 percent in Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). Somebody would need to have a lot of extra time on their hands to keep on top of an allocation like that. You can probably think of better things to do.

The 3 percent signal plan includes the safety measures financial planners are trying to achieve with additional asset-class allocations. The only distinction among asset classes that matters is volatility, and you should see it as a light switch, either on or off. In 3Sig, the stock side is volatile, the bond side is not. For most of your working years, keeping 80 percent of your capital in the most volatile, highest-performing major asset class, small-cap stocks, will produce the best performance. The 20 percent bond position provides you with buying power to boost performance even more after market sell-offs, and emotional comfort from taking advantage of volatility rather than fearing it.

Once you’re within ten years of retiring, you’ll decrease your stock exposure to 70 percent and boost bonds to 30 percent, with a new rebalancing demarcation of 40 percent bonds. If your bond balance reaches 40 percent during this phase, you’ll take advantage of the next buy signal to move in the excess and reset your target allocation at 70/30 stocks/bonds. Within five years of retirement, you’ll adjust the target allocation to 60/40, with a 50 percent bond rebalancing demarcation line. After you enter retirement, you’ll decrease stock exposure by ten percentage points each five years until stopping at a 20/80 stock/bond mixture once you’re fifteen years into retirement. Because the bond allocations are so high during the retirement years, the rebalance demarcation line moves up only 5 percent each time. Thus, at fifteen years into retirement, with a 20/80 stock/bond allocation, the rebalance happens at 25 percent bonds.

The 3Sig plan is best used as a working-years capital growth engine. The addition of new money from your income, plus the recovery potential inherent in the many years until you retire, provide it with the fuel and room to breathe that it needs. Closer to retirement and into retirement, capital growth becomes less important than capital preservation and income. The rising bond allocation addresses the need to preserve your capital and also provides income.

You might even conclude that 3Sig did its job for you over your working years, but now that you’re retired, you want to retire from the plan, too. If so, you could stop running 3Sig and adopt a traditional split of your retirement capital with maybe a third in a large-cap stock index that pays dividends, a third in a bond index, and a third divided between Treasuries and cash. A mixture like that can sit through anything, neither growing much nor losing much, which is acceptable in retirement.

Either way, whether you keep 3Sig going with a larger bond portion for income in retirement or stop the plan in favor of a conservative portfolio mixture in retirement, you’ll merely be deciding how to handle the large asset base created by the plan’s 80/20 stock/bond mixture run during the majority of your working years. As long as you don’t suddenly lose your mind and start trading on z-val advice, you should be fine.

Pulling It All Together

With the addition of these money management techniques to your 3Sig plan, you have a nearly unassailable way to grow your retirement without any interference from z-vals or Peter Perfect.

You’ll build your regular contributions into your growth target, earmarking half the total to the stock side and leaving the other half on the bond side. This will put half your new money to work in stocks at the end of every quarter, providing you with much of the benefit of dollar-cost averaging, and you’ll also keep half in bonds for future buying power. When the market goes up for an extended period of time or in a bubbly manner, telling you to sell and pushing your bond balance to more than 30 percent of your account value, you’ll automatically rebalance it back to 20 percent at the first buying opportunity. When the market goes down and puts shares of your stock fund on sale, you’ll be able to take advantage of it by buying more shares with the bond balance you set aside, in almost all cases. On rare occasions, the plan might exhaust its bond balance in an extreme downturn, in which case you’ll turn to whatever you’ve stashed away in your bottom-buying account to take advantage of the unusually cheap prices. If you ever exhaust even that account, you’ll follow the signal to remain in place for the recovery.

The 3 percent signal puts your cash contributions to work in good times and bad, high-volume inflection points and low-volume plods ahead. Watching the machinery at work every quarter assures you that you’re on top of things, that you need not “dive in and take control” amid tempestuous headlines fanning the wrong flames.

Most of the time, your bond balance will stay at around 20 percent of your account, achieving the base stock-to-bond ratio of 80/20. If it ever reaches 30 percent, you’ll move the excess into stocks at the next buy signal. When that arrives, and the z-gang talks about the market having a disappointing quarter and looking ready to move lower, you’ll take advantage of this with a buy order and remain agnostic as to where the market will go next. You have no idea, and neither do they.

The modified growth target that incorporates your contributions into the plan, and the rebalancing technique that keeps your bond balance correct, are flexible enough to handle whatever life throws your way. When your salary grows and your quarterly contributions increase, you’ll just up the amount you build into your growth target. Temporarily between jobs, with no quarterly contribution? No problem, just drop the contribution to zero. Get a windfall of cash that you want to add to the plan? Dump it in the bond fund. If it takes the bond percentage to 30 percent, let the plan signal when to put that windfall to work in stocks while also moving your mixture back to the base 80/20 ratio. As you get older, you’ll adjust this ratio to a lower percentage in stocks and a higher percentage in bonds.

Where do the z-vals fit in? Nowhere. You’ll run circles around them using only these techniques and a calculator, just four times per year, while they froth at the mouth daily in the creation of their one reliable product: noise.

Executive Summary of This Chapter

Contributing more cash periodically is common for long-term investment plans. The 3Sig plan handles incoming cash in unique ways. Large balances should be invested gradually. Smaller, regular contributions will initially go into your bond fund, but half their value will be added to the 3 percent growth target, to draw new capital into the plan. A “bottom-buying” account outside the plan can power signals during rare buying opportunities that require more capital than you have in your bond fund. Key takeaways:

To avoid the shock of investing a large cash balance just before a market drop, divide the cash into four equal batches and distribute them over the next four quarterly buy signals.

To avoid the shock of investing a large cash balance just before a market drop, divide the cash into four equal batches and distribute them over the next four quarterly buy signals. Our base plan’s target allocation is 80 percent stocks and 20 percent bonds, which will fluctuate with the market. When the bond allocation exceeds 30 percent, rebalance it back to the 80/20 target.

Our base plan’s target allocation is 80 percent stocks and 20 percent bonds, which will fluctuate with the market. When the bond allocation exceeds 30 percent, rebalance it back to the 80/20 target. The stock market rises over time, so you need to leave some of your cash contributions in your bond fund to maintain a proper allocation and buying power.

The stock market rises over time, so you need to leave some of your cash contributions in your bond fund to maintain a proper allocation and buying power. The best division of cash contributions is 50 percent. All new cash goes into your bond fund, but you’ll add half of its value to the growth target to draw new capital into stocks. The growth target formula is: stock balance + 3% growth + 50% of new cash.

The best division of cash contributions is 50 percent. All new cash goes into your bond fund, but you’ll add half of its value to the growth target to draw new capital into stocks. The growth target formula is: stock balance + 3% growth + 50% of new cash. For most of your working life, the reasonable fluctuation zone around the base 80/20 stock/bond target allocation is between 70/30 and 90/10. As you grow older, you’ll adjust stocks lower and bonds higher, and move the rebalance trigger up.

For most of your working life, the reasonable fluctuation zone around the base 80/20 stock/bond target allocation is between 70/30 and 90/10. As you grow older, you’ll adjust stocks lower and bonds higher, and move the rebalance trigger up. When your bond allocation hits its rebalance trigger after a quarterly action (30 percent when the stock/bond target mix is 80/20), use the next buy signal to move the excess bond balance into your stock fund to regain the target ratio.

When your bond allocation hits its rebalance trigger after a quarterly action (30 percent when the stock/bond target mix is 80/20), use the next buy signal to move the excess bond balance into your stock fund to regain the target ratio. To react intelligently in rare moments of extremely good buying opportunity, keep a bottom-buying account of savings outside the plan. It can be funded at a leisurely pace because it will almost never be needed.

To react intelligently in rare moments of extremely good buying opportunity, keep a bottom-buying account of savings outside the plan. It can be funded at a leisurely pace because it will almost never be needed. If you ever exhaust your bond balance and bottom-buying account, you’re vulnerable to doing precisely the wrong thing: bailing at the bottom. The plan can still help you by issuing buy signals that encourage you to hold on for the eventual recovery.

If you ever exhaust your bond balance and bottom-buying account, you’re vulnerable to doing precisely the wrong thing: bailing at the bottom. The plan can still help you by issuing buy signals that encourage you to hold on for the eventual recovery.