Big Business, Structural Transformation, and Development

Every year the biggest companies in emerging markets employ more and more people. Mexico’s largest private employer is Walmex, with nearly 250,000 employees. The company was founded as Cifra by Jerónimo Arango in 1952 and acquired by Walmart in the 1990s. Arango is now worth $4.6 billion. Mexico’s second-largest private employer is Femsa, the leading beverage company in Latin America, with over 200,000 workers, owned by billionaires Eva Gonda Rivera and José and Francisco Calderón Rojas. Other members of the superrich founded companies like BRF in Brazil, Cencosud in Chile, and Midea in China, all of which employ more than 100,000 workers each.

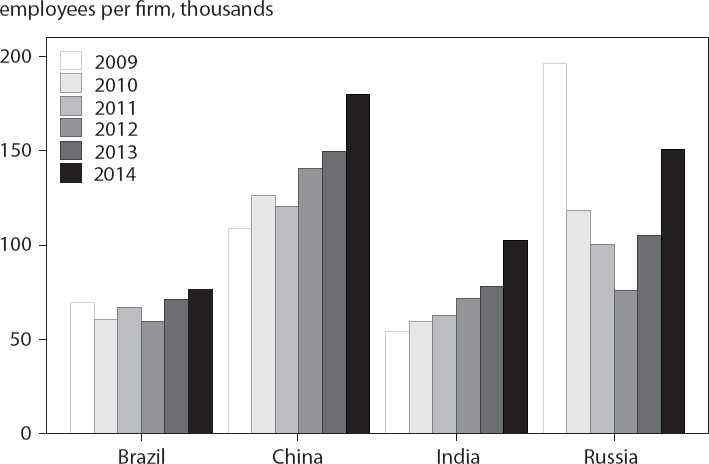

The Financial Times (FT) Emerging Market 500 list reflects this trend. In 2011, when the list was launched, 16 million people worked at the top 500 largest emerging-market companies. By 2014 the figure had risen to 19 million. The number of employees per firm on the FT Global 500 has risen in each of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) economies (figure 5.1).

This chapter examines how these superentrepreneurs and their mega firms contribute to the process of structural transformation. It shows that these large-scale employers move workers out of agriculture and into more productive jobs in factories and retail, which offer higher pay and a path to a different life. This force is unique in the emerging markets because these economies are still industrializing. In contrast, in advanced countries structural transformation is at a later stage, with workers moving out of industry into services.

This positive effect of mega firms on employment contrasts sharply with the often-reported deplorable working conditions in large developing-country factories. For example, the 14 suicides at Foxconn in China and the fire at the Tazreen Fashion factory in Bangladesh, which killed more than 100 people, are appalling. But it is also true that the millions of workers who leave more difficult rural lives are able to earn more working in factories, thus taking their first steps out of poverty.

Figure 5.1 Average employment per FT Global 500 firm in the BRIC countries, 2009–14

Source: Data from FT Global 500.

Leslie Chang, a Wall Street Journal reporter who lived in China for 10 years, writes about employment opportunities from the workers’ perspectives in her book Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. She followed two migrant workers in Dongguan, a factory city in South China, for three years. She found that although the work was hard, the women were optimistic, because the factories offered them social mobility—the potential for a better life with many more options than their rural villages offered. Returning with one of the women to her home village, she discovers the poverty and boredom that spurred their departure.

Despite some hiccups, mega firms have increased living standards and growth in most emerging markets. Factory jobs are better than subsistence farming, and they offer the potential for mobility for those able to train for such work. Mega firms and the innovative entrepreneurs behind them are a necessary part of the path to modernization, because they are a large and immediate source of jobs. The early stage of development is contingent on the presence of globally competitive firms and moving people out of agriculture and into industry.

Projected Increases in Extreme Wealth in Emerging Markets

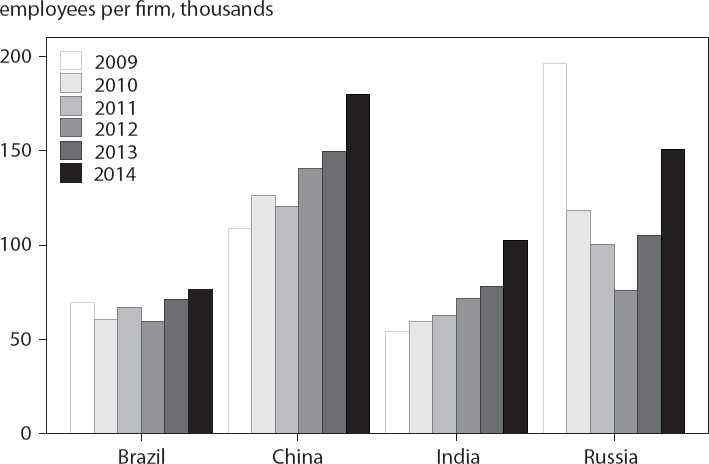

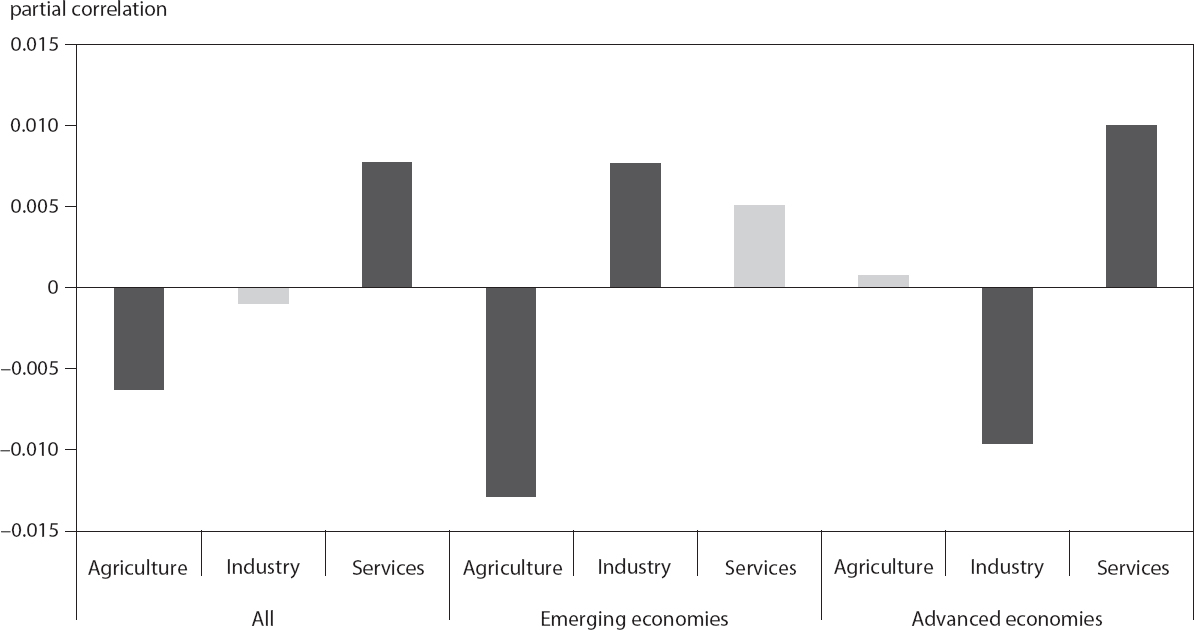

The number of extremely wealthy individuals in emerging markets is rising rapidly. By 2023 the share of billionaires in emerging markets will equal or exceed the share in advanced countries, and about one-third of the people worth $100 million or more will live in emerging markets (table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Emerging-market share of world’s wealthiest people, 2003, 2013, and 2023 (percent of total)

Source: Author’s estimates using data from Knight Frank.

Extreme Wealth and Structural Transformation

Unlike some advanced countries, where median incomes have stagnated and the employed share of the population has declined, manufacturing employment and wages in China have been rising rapidly. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that from 2002 to 2009, 13 million people entered manufacturing in China (nearly the size of the US workforce in manufacturing) (Banister 2013). Over this period, average manufacturing wages nearly tripled.

This type of rapid structural transformation—the move out of agriculture and into industry—is a standard feature of development. Margaret McMillan, Dani Rodrik, and Inigo Verduzco-Gallo (2014) show that Asia’s recent growth has been stronger than Latin America’s and Africa’s mainly because of the structural change that moved employment into the most productive manufacturing industries in Asia, but which failed to materialize in the other regions. Figure 5.2 documents the relationship between GDP per capita and the number of billionaires per 100 million people and the sectoral composition of employment. As countries develop, the number of billionaires rises (top panel). The structural transformation that accompanies the development process coincides with the movement of labor from the agricultural sector into manufacturing and services (bottom panel). As countries develop, the share of labor in agriculture declines and service employment increases, especially in the later stage of development. The share of employment in industry rises until per capita income reaches about $25,000 (in constant 2011 international dollars) and then declines.

Figure 5.2 Correlation between extreme wealth and structural transformation, 1996–2014

PPP = purchasing power parity

Sources: Data from World Bank, World Development Indicators; and Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

An important question is whether large-scale entrepreneurship and the extreme wealth that comes with it hasten structural transformation or are merely outcomes of structural transformation and growth. Put differently, controlling for stage of development, is the presence of a higher density of extreme wealth associated with more rapid structural transformation?

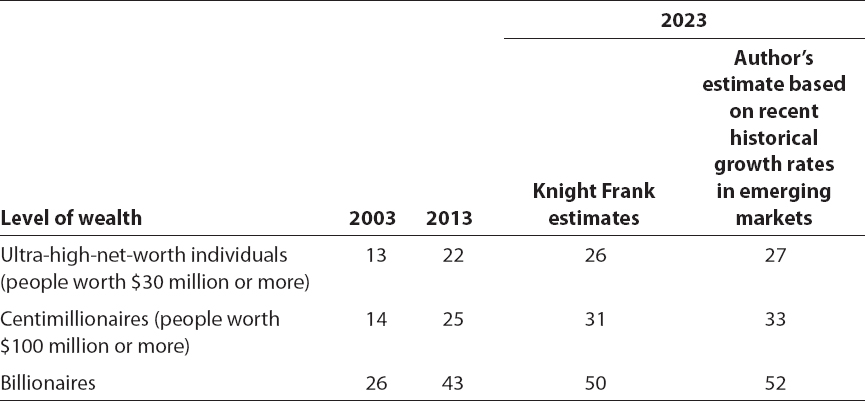

One way to answer this question is to examine the correlation between wealth and structural transformation, controlling for country-specific characteristics and the stage of development. Even controlling for country-specific factors that do not change over time, such as geography and relative size, and controlling for per capita income, countries that create more billionaires also move more rapidly to the next stage of development—from agriculture to industry in the South and from industry to services in the North (figure 5.3).1

Holding country-specific factors and income growth constant, agricultural employment in an emerging-market country where the number of billionaires rises from two to four would be expected to decrease by nearly 2 percentage points more than in a country that did not witness the same expansion in extreme wealth. The results shown in figure 5.3 are consistent with the notion that billionaires and their mega firms accelerate structural transformation at early stages of development.

Self-Made Founders Employ the Most People

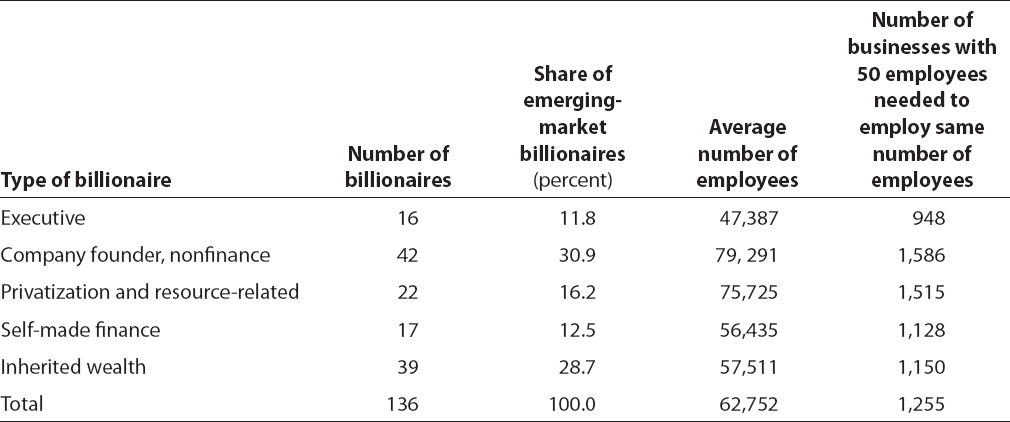

How many workers are directly employed by the rich? Of the firms on the 2014 FT Emerging Market 500 list, 109 are connected to one or more billionaires. Table 5.2 shows the average number of employees according to the type of billionaire connected to these companies. Company founders employ the largest number of people, with an average of 80,000 employees in the companies they started. Given that by definition their firms are new firms, all of these jobs are new ones (job creation).

Compared with small business (table 5.2, column 4), billionaire firms perform well in terms of job creation. The total direct employment from this select group of firms remains small, however: The nearly 700 emerging-market billionaires employ about 44 million people or just over 1 percent of the 4 billion people of working age in emerging markets. Considering that the big firms are not meant to employ all of a country’s workers but to enhance the pull out of agriculture, the numbers are a bit higher. In China, for example, about 320 million people work in agriculture. If each billionaire employed 63,000 people (the average in table 5.2), China’s 151 newly minted billionaires would have absorbed about 10 million workers from 2002 to 2014, only about 3 percent of the agricultural sector, but a substantial number compared with the 13 million workers who, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates, moved into manufacturing from 2002 to 2009 (Banister 2013).

Figure 5.3 Correlation between extreme wealth and employment by sector in advanced countries and emerging economies, 1996–2014

Note: Bars report the coefficients on the log of the number of billionaires from the regression of the share of employment by sector on the log of billionaires, country fixed effects, and the log of GDP per capita. Dark gray bars indicate significance at the 1 to 5 percent level.

Source: Author’s calculations.

Table 5.2 Employment by emerging-market billionaires, 2014

Note: Figures are based on billionaires associated with FT Emerging Market 500 firms, a list that excludes Israel and Hong Kong. Small businesses are companies with fewer than 50 employees.

Sources: Data from the FT Emerging Market 500 and Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

These direct calculations may understate the importance of big business in structural transformation for several reasons. First, billionaires are the focus of this book because their businesses are identifiable and a long cross-country time series is available on them. But their presence is meant to capture more broadly the big business environment and the type of businesspeople (origins and sectors) a country is developing. In reality, many large-scale entrepreneurs, not just billionaires, bring about structural transformation. The cross-sectional correlation between the populations of centimillionaires and billionaires is very high for the years available (0.95), implying that the effect of the superrich could be picking up this broader group, which employs a much larger share of the workforce.

Second, these direct job numbers underestimate the value of each business, because they ignore spillover effects on upstream and downstream industries. For example, makers of pharmaceuticals purchase chemicals and machinery to produce their products and use logistics and retail outlets to get their products to market. The estimates also ignore income effects, as employees spend money on consumer goods.

Third, the superrich have many additional businesses other than their main source of wealth, which are not included in these calculations. For example, Robin Li, founder of Chinese internet company Baidu, which employed 46,000 people in 2014, has ownership stakes in 51 companies, which together employ an additional 33,000 people.

Emerging-Market Firms Displace Advanced-Country Firms

Emerging-market companies are growing rapidly, overtaking advanced-country firms at the top of the Forbes Global 2000 list. As recently as 2009, all 10 of the world’s largest firms were advanced-country firms. In 2010 the Chinese bank ICBC became the first emerging-market company to be part of the top 10; by 2014 Chinese banks captured the top three places on the Global 2000 list, with a fourth Chinese bank taking the number 10 spot.

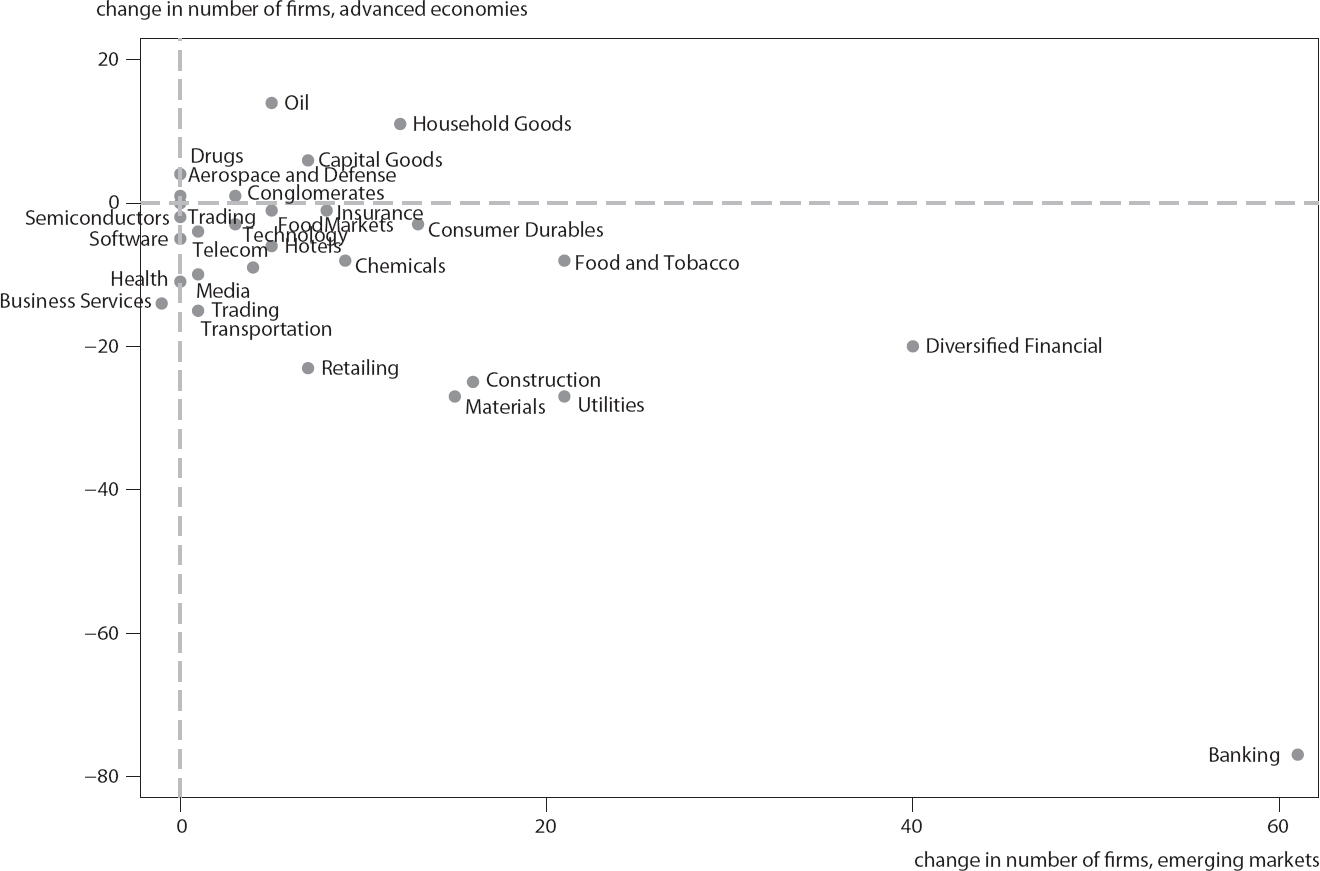

Figure 5.4 shows the change in the number of advanced-country and emerging-market mega firms between 2006 and 2014 by sector. Most industries fall in the bottom right-hand quadrant, where firms are entering from the South and exiting from the North. In banking, for example, 61 emerging-market firms joined the list between 2006 and 2014 and 77 advanced-country firms exited.

In others sectors the growth of mega firms in the North and the South is more even, with both groups showing rising shares. These sectors (shown in the upper-right-hand quadrant) include household goods, oil, and capital goods. Growing emerging-market demand helps explain these booming global sectors. As the number of consumers in the world grows and they get richer, demand for household goods rises. The infrastructure investment needed for structural transformation also boosts global demand for capital goods and oil.

The South has seen big gains in materials producers, such as Jiangxi Copper (China) and Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel (Russia). This shift is also related to structural transformation. As emerging markets play a bigger role in the global economy, there is more demand for raw materials, such as steel and coal, to build industry.

Business school professors, investors, and consulting companies are closely watching these emerging-market mega firms. Studies of their extraordinary growth have incited fears that they will steal consumers from established advanced-country firms. Typical titles include Emerging Markets Rule: Growth Strategies of the New Global Giants (Guillén and García-Canal 2013), The Emerging Markets Century: How a New Breed of World Class Companies Is Overtaking the World (van Agtmael 2007), and The Rise of the Emerging-Market Multinational (Accenture 2008).

Figure 5.4 Replacement of mega firms from advanced countries by mega firms from emerging markets, by sector, 2006–14

Source: Data from Forbes Global 2000, 2006 and 2014.

Figure 5.5 Stock of outward foreign direct investment by developing and developed economies, 1981–2013

Source: Data from UNCTADstat Database, Foreign Direct Investment Flows and Stock, http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportfolders.aspx.

Fear in advanced countries stems from the new competition in product markets and investment. In 2008 Tata Motors of India acquired Jaguar Land Rover for $2.3 billion—slightly less than what Ford paid for Jaguar alone in 1990. A bigger surprise than the purchase itself was the fact that Tata was far more successful than Ford was in reorganizing the company. In just a few years, sales tripled and 9,000 employees were added, and Tata plans to hire more.

In 2004 Ambev, a Brazilian brewer, merged with Interbrew of Belgium to access European markets. Initially, Inbev, the combined company, had a European head, but within about a year a Brazilian, Carlos Brito, took over. Belgium’s economy minister bemoaned the fact that the company was “totally Belgian, then it was Belgian-Brazilian, and now it’s Brazilian-Belgian.”2 Brito is known for his cost cutting (gone were the days of a plush senior management floor and free cases of beer for employees). His efforts helped Anheuser-Busch Inbev more than double its stock price after the 2008 merger with Anheuser-Busch despite a stagnant US beer market.

Acquisitions of advanced-country multinationals by emerging-market firms are becoming common. Saudi Basic Industries Corporation acquired GE Plastics; Russian company Severstal bought Rouge Steel (US) and Lucchini (Italy). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), outward foreign direct investment (FDI) from emerging markets increased nearly sixfold between 2000 and 2014, about twice the increase from developed countries, to account for 20 percent of the total stock of FDI (figure 5.5 located on page 96).

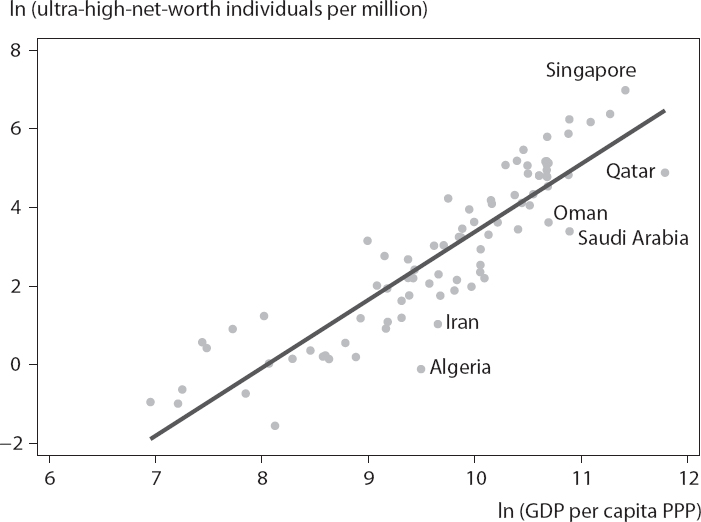

Figure 5.6 Correlation between density of ultra-high-net-worth population and stage of development, 2013

Source: Knight Frank (2014).

Is Extreme Wealth Necessary?

Entrepreneurs and mega firms are the source of industrialization. Extreme wealth is, therefore, part of development, especially at the beginning of the process, as countries achieve middle-income status. But is extreme wealth necessary? Is it possible to build big productive firms without a few individuals taking such an enormous (and seemingly unfair) share of the pie?

It is very hard to find examples of expanding country income without the emergence of extreme wealth. Across countries the stage of development and the presence of extreme wealth are very highly correlated (see also chapter 4).

Figure 5.6 shows ultra-high-net-worth density and GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP). Data on ultra-high-net-worth people (defined as people worth $30 million or more) include more countries than billionaire data, because many small countries have no billionaires. The high-income countries that fall farthest below the fitted line (where countries are rich but there are few billionaires) are the oil-rich countries in the Gulf. Although these countries are rich, they have failed to industrialize outside of oil, and new businesses in other sectors are not growing or developing significant ties with the rest of the world. Most billionaires are royals, who do not show up in the data. Aside from families with access to oil wealth, there are very few superrich. The region lacks the company founders and executives who create new products and processes.

Singapore is at the opposite extreme of the oil-rich countries. Until recently it was poor, but thanks to its openness to trade and investment, it now has more millionaires per capita than any other economy in the world. With a population of just 5 million, it hosts 16 billionaires. Most are self-made, and many own innovative businesses. Sam Goi, the “popiah king” (described in chapter 3), is one of them.

Takeaways

As startups grow into mega firms and wealth expands, firms pull resources out of agriculture and put them in industry. These firms create better jobs for a country’s population and more opportunities for advancement. This process is different in advanced countries, where resources are already largely in industry and services. The expansion of extreme wealth in advanced countries is associated with a shift of labor out of industry into services.

1. The results are highly significant despite the fact that industrialization has gotten more difficult since 1990 as a result of labor-saving technologies and globalization (Rodrik 2015).

2. Tim Bowler, “The Brazilian Recipe for Brewing Success,” BBC, July 14, 2008.