Policies for Promoting Innovation and Equity

How far should the government go to foster big business in developing economies? Development institutions such as the World Bank urge governments to focus on securing property rights, ensuring the free entry and exit of firms, and opening up to trade and foreign investment. These features are important for creating an atmosphere in which businesses can grow. But in developing economies, reform can move slowly, access to finance is limited, and uncertainties abound. Should governments there do more to promote transformative, large-scale entrepreneurship?

This chapter begins with the most basic mechanisms for efficient resource allocation: property rights, free entry, and openness to trade and investment. It then discusses the potential for promoting entrepreneurship to spur modernization. The intuition from firm-level research is that success involves facilitating the development of large enterprise and forcing firms to compete globally. The chapter also discusses ways to reduce wealth that is not associated with entrepreneurial talent.

Creating an Environment that Is Conducive to Growth

Resources flow to the most productive uses when commerce is encouraged. William Baumol (1990) underscores the importance of creating rules that incentivize productive activity. He shows that in ancient Rome, productive enterprise was not well rewarded and technology did not spread. The water mill, for example, was developed in the 1st century BC but was little used then, except occasionally to mill grain. Under the Sung Dynasty in China (960–1270), all property belonged to monarchs, and wealth and prestige were reserved for people who studied Confucian philosophy and calligraphy. Innovations in paper, printing, the compass, waterwheels, water clocks, and gun powder occurred during this period, but the absence of property rights hindered the spread of industry based on these major discoveries. In contrast, during the High Middle Ages and the 18th century Industrial Revolution, entrepreneurship was well rewarded; in both periods innovation spread rapidly. Using these and other historical examples, Baumol argues that when the rules of the game favor entrepreneurship, it flourishes; when they do not, even great ideas do not spread.

Kevin Murphy, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny (1991) develop a theoretical model that identifies the three main factors that make entrepreneurship, as opposed to rent seeking or other less socially valuable choices, more attractive: property rights, firm entry, and openness to trade. Property rights allow people to build their companies without fear of expropriation.1 Easy entry and expansion of firms allow talented people to create firms and grow them quickly. Trade provides a large market for goods and ensures that price incentives are correct, guiding resources to their most productive uses. Business turnover and trade ensure that entrepreneurs compete in contestable markets. They are precisely the ingredients that are coming together in the developing countries where company founders are thriving and commerce is growing rapidly.

Ensuring Ease of Entry

Hernando de Soto demonstrated the onerous nature of business regulations in Peru. In 1983 his research team tried to establish a garment factory in Lima. After 289 days, 11 requirements, and direct costs 31 times the average monthly wage, they succeeded (Clilft 2003). De Soto (1989) attributes the prevalence of informal businesses in Peru to excessive regulation. Businesses stay small and informal because becoming big is very costly. As a result they lack access to capital, and markets remain uncompetitive. The high cost of regulation partly explains why it took so long for emerging markets to begin producing the mega firms that succeed on global markets.

The World Bank’s Doing Business project is built on de Soto’s work. Doing Business indicators provide a means to compare business regulations across countries. The first indicator developed was ease of business entry, which measures how long it takes to register a typical business. Research using the data shows that countries in which business entry is easier have less corruption and tend to be richer (Djankov et al. 2002).

Ease of business entry ensures that the most productive firms are in the market. Lean regulation also prevents government bureaucrats and intermediaries from extracting rents. When regulation is burdensome, requiring complex paperwork and approvals, government officials can solicit bribes to smooth the process, and intermediaries who understand the business can flourish.

Brazil is known for excessive regulation, though in recent years conditions have been improving. In 2005, according to Doing Business indicators, it took 152 days to start a business, more than three times as long as in China or Russia and twice as long as in India. Brazilians use the word despachante (meaning customs agent or dispatcher) to refer to the intermediaries who flourish when regulations are excessively complex. Their prominence is revealed in John Grisham’s 1999 novel The Testament (p. 376):

The despachante is an integral part of Brazilian life. No business, bank, law firm, medical group, or person with money can operate without the services of a despachante. He is a facilitator extraordinaire. In a country where the bureaucracy is sprawling and antiquated, the despachante is the guy who knows the city clerks, the courthouse crowd, the bureaucrats, the customs agents. He knows the system and how to grease it. No official paper or document is obtained in Brazil without waiting in long lines, and the despachante is the guy who’ll stand there for you. For a small fee, he’ll wait eight hours to renew your auto inspection, then affix it to your windshield while you’re busy at the office. He’ll do your voting, banking, packaging, mailing—the list has no end.

Excessive regulations create delays and impose extra costs on businesses. They also divert resources into unproductive activities like those performed by despachantes.

Brazil has improved its Doing Business indicators, reducing the number of days required to start a business by almost half since 2005. It is replacing business registration and customs bureaucracies with electronic one-stop shops. The great advantage that new technology brings is that it is not corruptible. Getting rid of excessive bureaucracy in busines entry is an important step in development, because it facilitates business development and expansion and helps direct talent to more productive uses.

Opening Up to Trade

Entrepreneurs can build mega firms only if the market for their product is large. Small countries need trade to reach such markets; the growth of a company that exports is not constrained by country size. Openness also allows companies to access inputs needed for production.

Beyond providing a large market, openness to trade ensures that price incentives are correct, steering firms to produce the most competitive products. When tariffs are high, it becomes more profitable to produce import-competing goods than exported goods, despite the fact that producing such goods does not represent the best use of a country’s resources. The nearly 800 percent tariff on imported rice in Japan is an extreme example of how protection directs production to goods that are not aligned with a country’s comparative advantage.

The growth literature shows an additional benefit from jointly pursuing ease of business entry and trade liberalization. When economists examine which countries have benefited from increasing trade they find that trade leads to a higher standard of living in flexible economies but not in rigid economies (Freund and Bolaky 2008; Chang, Kaltani, and Loayza 2009). The intuition is that trade provides the right price signals for the best businesses to grow but that ease of entry and exit are important for resource reallocation to actually happen. If there are constraints on business creation, superstar firms may never be born. Analysis shows that business regulation, especially on firm entry, is more important than financial development, higher education, or rule of law as a complementary policy to trade liberalization. After controlling for the standard determinants of per capita income, a 1 percent increase in trade is associated with more than a 0.5 percent rise in per capita income in economies that facilitate firm entry but has no positive income effects in more rigid economies (Freund and Bolaky 2009). The findings support firm-level studies showing that the beneficial effects of trade liberalization result largely from moving resources to the most productive firms. If new firms cannot enter and the best firms cannot grow, the gains from trade are largely absent.

Undervaluing the Exchange Rate

The real exchange rate is a critical price determining global competitiveness and hence a complement to open trade policies. It is a measure of the ratio of domestic costs to foreign costs, using the same basket of goods in the same currency.2 Preventing overvaluation is important because it pushes resources toward the nontradable sectors as tradables become less competitive: Imports will outperform domestically produced competing goods, and exports will become costly abroad. Given that nontradables are produced in inherently less contestable markets, such an outcome is bad for development. It prevents the most productive firms from growing through foreign markets. A large and growing body of evidence finds that an undervalued real exchange rate helps countries grow precisely because it pushes resources into the tradable sector (Hausmann, Prichett, and Rodrik 2005; Jones and Olken 2008; Bhalla 2012; Freund and Pierola 2012).

Profiting from Foreign Direct Investment

Another way to move resources to their most efficient uses and develop large firms rapidly is through foreign direct investment (FDI). Singapore used this strategy effectively, as noted in chapter 4. Foreign firms invested in the country to take advantage of low labor costs and a relatively good business climate, and a domestic logistics industry developed around the growing manufacturing sector. Singapore remains a hub for foreign investment, but it has also developed its own multinationals. China’s development strategy has also benefited from large joint ventures with foreign firms, which raised productivity, revealed China’s potential for trade, and highlighted the importance of global supply chains.

Attracting the largest multinationals can have important aggregate effects. Many of the top exporters in a typical developing country are foreign multinationals. For years Costa Rica’s top exporter was Intel.3 Vietnam’s leading exporter is Samsung. These large firms require inputs and logistics; demand by them improves the business climate. The success of one large multinational attracts other multinationals, further improving resource allocation. After Intel’s arrival in Costa Rica, for example, companies such as Infosys and Hewlett-Packard moved in. Big investors like Texas Instruments, Motorola, and HP helped Bangalore, India, develop. The region later created blockbuster technology firms of its own, such as Infosys and Wipro.

A growing body of literature shows that FDI has positive effects on domestic business. Spillovers to firms in the same industry have been hard to find, but evidence shows strong positive effects on upstream industries in the home country (Javorcik 2004, Blalock and Gertler 2008). Foreign firms require high-quality inputs; to obtain them, they help local suppliers upgrade their products. Foreign-owned firms also teach domestic firms how to trade. Former managers with knowledge of global markets may start their own companies, or the foreign firm’s success may provide information to domestic businesses about the value of trade. In Mexico, for example, proximity to multinational firms increased Mexican firms’ likelihood of becoming exporters (Aitken, Hanson, and Harrison 1997).

In order for FDI to spur development, markets must be competitive. When foreign businesses are profitable because of market barriers, they may seek to maintain or expand them, hurting growth. In contrast, when foreign firms take advantage of resource endowments in a competitive market, they use resources more effectively. Theodore Moran (2011) finds that the extent of competition in the market in which the investment occurs is the most important factor in determining how positive the effect of FDI is.

Adopting Industrial Policy that Promotes Large-Scale Entrepreneurship

A good business climate is necessary for business to flourish, but it may not be sufficient, especially in a world of large enterprises, which require substantial financing. Large US steel and rail companies developed with government subsidies; major Japanese car companies grew under family control, with financing from their own banks sanctioned by the government.

In the most rapid recent industrializers, the state was heavily involved in both running enterprises and promoting large-scale entrepreneurship. In Korea the chaebol-controlled firms began their ascent in the 1960s and 1970s, with assistance from special tax treatment and low-interest loans. The export promotion policies of President Park Chung-hee shaped the global footprint of firms like Samsung, LG, and Hyundai. “Mammoth enterprise—considered indispensable, at the moment, to our country—plays not only a decisive role in the economic development and elevation of living standards,” wrote Park, “but further, brings about changes in the structure of society and the economy” (Park 1962, 228–29). These firms undeniably helped Korea develop: Today Samsung alone accounts for about 20 percent of the Korean economy.

Following the success of Korea and the other Asian Tigers with industrial policy and export-led growth, Latin American governments experimented with export-promotion policies in recent decades. Their efforts were mostly on a small scale, targeting many firms with tax incentives and cheap loans. To promote nontraditional exports, for example, the Dominican Republic experimented with subsidized government loans of up to $500,000; Costa Rica offered tax credits to exporters of nontraditional goods. These programs enjoyed modest success, but they failed to generate the kind of large-scale entrepreneurship that transforms an economy. Why were export-oriented industrial policies in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan successful while attempts in much of the rest of the world were not?

Korea’s program involved three important features: export orientation, competition between large enterprises to receive benefits, and withdrawal of benefits when firms did not perform. Small domestic markets, which tend to have oligopolies, do not provide a good playing field on which to evaluate firm performance. Competing in foreign markets is a better gauge and provides companies with the demand needed for rapid growth.

External orientation is not sufficient, however; privately owned firms must compete and operate on a large enough scale to matter to the economy. Korea’s policy targeted not just the industry but also the firm. Global targets forced firms to compete for privileges, allowing only the best to grow rapidly.

The economic intuition behind industrial policy (defined as the government’s use of economic incentives to promote a particular sector) is that it compensates for a market distortion that prevents the optimal amount of investment, given social returns. Hefty initial investments and early losses may deter private investment, especially when access to finance is limited or other firms can learn from the first investor about a product’s marketability with smaller startup costs later, reducing future profitability of the pioneer. Production may be associated with learning externalities that firms do not internalize. For example, a manufacturer may benefit from improved production techniques and less waste over time, but not realize this before undertaking investment. A few large firms may need to be active in a sector or a region in order to make production and exporting profitable, because of logistics or upstream linkages. Under any of these conditions, the government may need to provide a push to get an industry started.

Economists have long recognized the theoretical possibility that market distortions exist that industrial policy could remedy, but most are skeptical about industrial policy working in practice, because of three main concerns: (1) governments are not good at “picking winners”; (2) the appropriate intervention (taxes or subsidies) depends on market structure and the nature of distortion, which varies by industry and can be difficult to identify; and (3) the process is highly corruptible, because choosing recipients is political. Resources are likely to flow to the best-connected sectors and firms rather than the most productive ones, while unproductive intermediaries and government officials enrich themselves at taxpayers’ expense. The cure may be worse than the disease.

An ongoing attempt at government-promoted private enterprise in Russia highlights these concerns. In 2009 President Dmitry Medvedev dreamed up the Skolkovo Innovation Center as Russia’s answer to Silicon Valley. The government spent more than $2 billion building a domestic high-tech sector, which it located in the neighborhood of Russia’s superrich to garner private sector support. So far the new center is providing high returns—albeit not of the kind planned. The innovation center’s figureheads were arrested on embezzlement charges in April 2013 and soon thereafter President Vladimir Putin reversed the tax and planning benefits offered to investors.4 As a result none of the large-scale investments ever materialized. Lack of transparency in government regulation and procurement has continued to skew incentives away from productive business development toward rent taking. A Korean-style model of competition for financing, using a metric that can be objectively measured, is needed.

Supporting Firms Rather than Sectors

Much industrial policy—especially failed policy—has focused on industries (often import-competing instead of export-oriented). The importance of large-scale entrepreneurship points to the potential usefulness of supporting firms as opposed to sectors. The government need not pick winners, international competition can do that, ensuring that financing goes to the right firms and graft is reduced.

Industrial policies that have succeeded in creating global firms and starting new industries share three important features. First, they encourage investment in the export sector. Second, rather than spreading money across a swath of firms, they target a few private domestic firms that compete for financing with other domestic firms by showing export success. Third, the government must be capable of running a fair contest among firms. Because it is very easy to hijack competition in a nontransparent system, countable output metrics (such as export targets and production growth) rather than input measures (such as research and development or hiring) should be used. Korea used bills of lading from the port to measure firms’ exports in the 1960s and 1970s, precisely because these documents could not be falsified.

One example of (eventual) success with this kind of industrial policy comes from Latin America. In 1969 the Brazilian government founded aircraft maker Embraer. As a state-owned enterprise, Embraer was a huge failure, with losses running into the hundreds of millions of dollars in the 1980s. To try to turn these mammoth government expenditures into revenues, the government privatized Embraer in 1994, but the firm continued to receive concessional financing. Júlio Bozano (now a billionaire) and his bank led the consortium of investors. They installed a business guru, Mauricio Botelho, with no aircraft experience, as CEO. Backed by a strong board, Botelho completely changed the company’s course. When it was privatized, Embraer was a mess, involved in a number of losing product lines. Botelho dropped all projects but one, the 50-seater jet. The move represented a big risk at the time, given the commanding position of the Canadian company Bombardier in this market. Following deep restructuring and concessional financing by the government, Embraer soon became highly profitable. Its success was solidified when it became globally competitive in the mid-1990s. Embraer now leads the regional jet market, with technology that Bombardier cannot match.5 “This is an example of how a strategy can make a company a success—or kill it if the strategy is wrong,” notes Botelho.6 External orientation, private enterprise, and scale all came together in Embraer, now a $5 billion company.

The Brazilian government’s financing was not as explicitly competitive as the Korean government’s was. Instead, large-scale private investors monitored the firm’s performance.

Identifying Market Distortion

One reason why highly productive firms may need government assistance to finance large investments is that financial systems are weak: Bank financing is unavailable (because property rights laws and credit registries are not in place) and stock markets are not developed. The legal environment for future earnings–based bank financing and stock market development is significantly weaker in developing countries than in advanced countries (LaPorta et al. 1997, Djankov, McLiesh, and Shleifer 2007, among many others). The absence of developed capital markets prevents high-performing firms in emerging markets from growing at their potential and expanding rapidly in foreign markets.7

Using a dataset of listed firms from 51 countries, Tatiana Didier, Ross Levine, and Sergio Schmukler (2014) show that in a typical country only a few of the largest firms issue securities. Firms that issue bonds or equity grow much faster than nonissuers. They find that in developed economies small issuers grow faster than large issuers, suggesting that small firms are most constrained. In contrast, in developing economies large issuers grow the fastest, suggesting that credit constraints are much broader and may disproportionately constrain the largest firms.

In most developing countries, equity and bond markets are underdeveloped, preventing firms from growing to potential. This finding dovetails with the literature on firm dynamics (discussed in chapter 3), which shows that the failure of the best firms to grow large over time constrains growth in developing countries. Government-supported financing and tax incentives can help firms with the potential to become large multinationals grow faster in emerging markets. It is, however, important that such policies be limited to additive financing (not financing that crowds out the private banking sector) and that they be phased out once a country develops a financial system capable of intermediating funds.

Limiting Unproductive but Profitable Activities

In addition to promoting entrepreneurship, government policy can reduce the extent to which resources go to activities that do little to boost (or actually reduce) aggregate welfare. Countries with sizable shares of inherited and financial sector wealth may be justified in taxing them.

Raising or Imposing Estate Taxes

Many countries apply estate and inheritance taxes on large transfers in order to mitigate the concentration of wealth.8 These taxes exempt the vast majority of wealth. In the United States, for example, the estate tax of 40 percent is charged only on estates above $5.43 million per individual, and only the amount by which the estate exceeds the exemption is taxed. In Korea a progressive inheritance tax ranges from 10 to 50 percent for net worth above 3 billion Korean won (about $2.55 million). In 2015 Japan raised its maximum rate from 50 to 55 percent and expanded the base.

Whether or not taxing inheritance makes economic sense depends on whether it distorts the productive behavior of the bestower. Opponents of estate tax argue that it discourages entrepreneurs from expanding their companies, because a central motive behind acquiring wealth is the desire to leave it to one’s heirs. They also worry that companies may be divided upon the death of the founder if their heirs do not have enough money to pay taxes and run the business. Estate tax might also encourage companies to move to lower tax jurisdictions or engage in costly and unproductive tax avoidance.

The first two concerns are largely theoretical. There is little evidence that bequests are at the top of founders’ minds. Indeed, Wojciech Kopczuk (2007) finds that much of estate planning among the wealthy elderly takes place only after the onset of a serious illness. Even if founders are considering succession plans, company leaders may actually work harder in the presence of an estate tax in order to leave a greater after-tax business to their children.

The evidence that the exclusion level for estate taxes greatly affects small businesses is weak. Donald Bruce and Mohammed Moshin (2006) find no significant effect of the US estate tax exclusion policy in effect from 1983 to 1998 on entrepreneurial activity, despite the comparatively low exclusion level of $750,000.

On the last concern, a host of resource needs, logistics requirements, lifestyle choices, and other tax considerations affect the choice of a company’s location. Research suggests that to the extent taxes matter for location, corporate taxes are much more important than estate taxes in affecting the location choice, and corporate taxes matter for the parent more than subsidiaries (see, for example, Markle and Shackelford 2012). Bermuda is a tax haven because it has no corporate tax, not because it allows wealthy people to avoid estate taxes. A moderate estate tax is unlikely to be a critical decision in where to locate business or where the wealthy choose to reside.

Estate taxes could actually have a positive effect, by encouraging heirs to work harder. As Andrew Carnegie famously said, “The parent who leaves his son enormous wealth generally deadens the talents and energies of the son and tempts him to lead a less useful and less worthy life than he otherwise would” (Carnegie 1891, 1962, A1). Douglas Holtz-Eakin, David Joulfaian, and Harvey Rosen (1993) offer empirical support for this conjecture. They use US tax return data from 1982 and 1983 and find that individuals who receive larger inheritances are significantly more likely to leave the labor force.

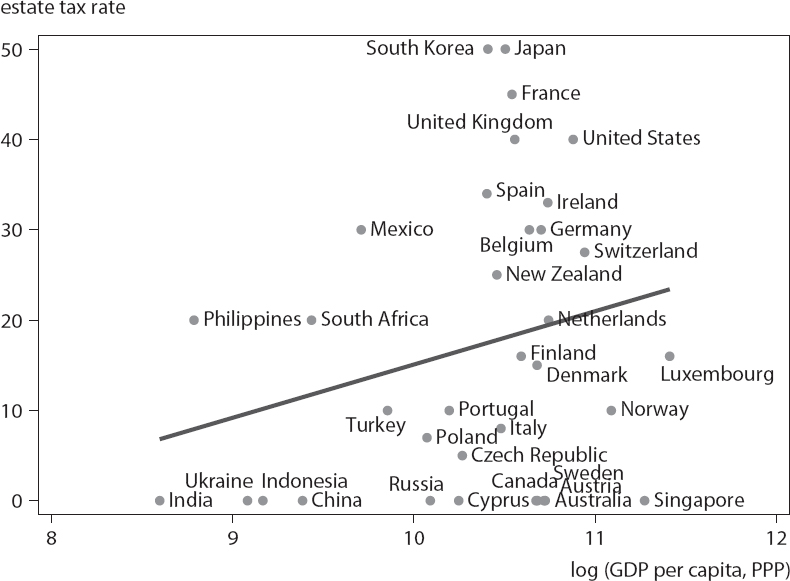

Figure 10.1 Correlation between per capita GDP and estate tax rate, 2013

PPP = purchasing power parity

Sources: Data from World Bank, World Development Indicators; and EY International Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2013.

The estate tax can be an important source of revenue and redistribution. In the United States, both the tax and the tax base declined substantially in the 2000s. In 2001 estate tax was imposed on estates greater than $675,000, at a rate of 55 percent; in 2015 the tax was imposed only on estates that exceeded $5.43 million, and the rate was 40 percent. As a result of changes in the law, nominal estate tax revenues fell from $216 billion in 2001 to $48 billion in 2011. (To put these figures in context, in 2001 estate tax revenue could have covered the cost of the food stamp program 14 times over. In 2011 the revenue could have covered just two-thirds of the program.9)

Estate taxes around the world vary significantly (figure 10.1). Although not all developed countries have high estate taxes (many rich countries, including Sweden and Singapore, have no estate tax at all), all of the countries with high estate taxes are developed countries. Many developed countries have low estate taxes.

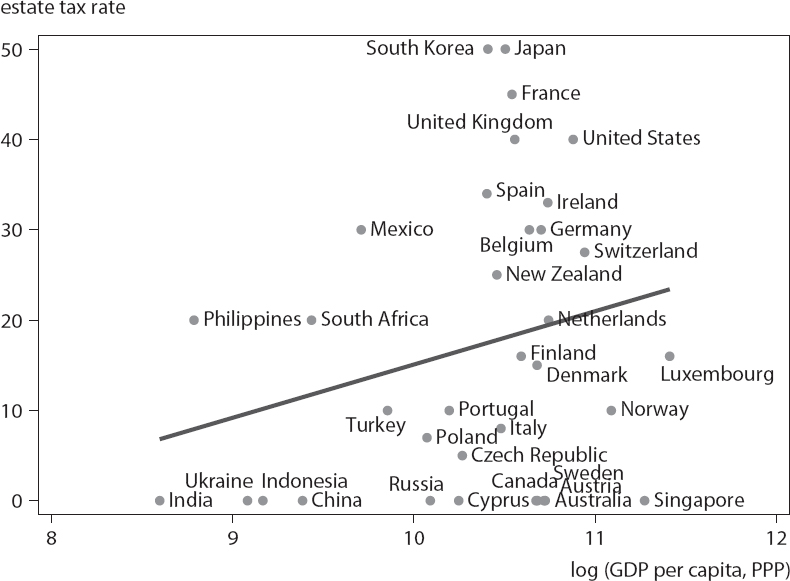

Figure 10.2 Correlation between share of billionaire wealth in advanced countries that is inherited and share of total tax revenue from legacy taxes

Sources: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires; and OECD revenue statistics database.

Figure 10.2 shows estate tax as a share of total tax revenue and the share of inherited billionaires in the North. It suggests that the advanced countries that have historically relied more heavily on estate taxes for revenue have managed to limit inherited wealth.

Estate Taxes Promote Philanthropy

A potential additional benefit of estate taxes is that they encourage philanthropy, as the wealthy seek to reduce the value of an estate before it is transferred. Frank Doti (2003) uses variation in US estate tax law to estimate the effect of taxes on philanthropy. The estate tax law of 1917 did not allow for deduction of charitable bequests. This oversight was rectified in 1921 (retroactive to 1918). Doti finds that between 1917 and 1921 gross estates increased 25 percent and charitable bequests increased 3,419 percent, which is more than 34 times the charitable bequests reported at the beginning of the period. His finding suggests that high tax rates encourage the wealthy to leave a larger share of their estates to charity.

The 19th century US industrialists were major philanthropists during their lifetimes. Their behavior may have been related to taxation, as well as the desire to leave a legacy. The federal estate tax was first introduced in the mid-1800s, but it was low (West 1980). It reached a temporary peak of 15 percent in 1902 before being repealed until 1916, when modern estate tax was enacted.10 It rose rapidly every few years, from 10 percent in 1916 to 25 percent in 1917, hitting 77 percent by 1941. Corporate and income taxes also rose.

The value of philanthropy in development is hard to quantify, but anecdotal evidence shows that it is important and, to the extent that estate taxes encourage it, that is an additional benefit of such taxes. Andrew Carnegie is probably the world’s best-known philanthropist. He died in 1919, when estate taxes were 25 percent and the maximum income tax rate was 73 percent. His foundation built more than 2,500 libraries. One study finds that the return on these libraries is six to one: For every $1 a city puts in, the library creates $6 in social return (Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh 2005). At least 6 of the 28 so-called robber barons are associated with major universities, including Leland Stanford, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie (Carnegie-Mellon), James Buchanan Duke (Duke University), and John D. Rockefeller and Marshall Field (University of Chicago). Two large foundations, Carnegie and Rockefeller, support development to this day.

The superrich of the 1950s also gave heavily to charity, in part because US estate taxes reached nearly 80 percent. James Chapman, an oil baron, left his $100 million fortune to universities (mainly the University of Tulsa) and medical institutions, leaving little more than their home to his wife and son. Hugh Roy Cullen, another oil man, left $30 million to the University of Houston and at least $20 million to hospitals. Amon Carter used his oil wealth to promote aviation, starting American Airlines. He put half his wealth into a charitable foundation (Lundberg 1968).

Historical examples of large-scale philanthropy in Europe are rarer, likely related to nominal inheritance or estate taxes on close relatives. The imperial inheritance tax in Germany, imposed in 1906, exempted children and other direct descendants. The French had a maximum rate of 5 percent for children. The British Empire set a maximum estate tax rate of 8 percent until 1907, when it was increased to 15 percent. The cantons of Switzerland, among the first to establish an inheritance tax in Europe, set maximum rates for immediate family below 3 percent.11

Emerging markets have yet to see the kind of large-scale philanthropy that existed in the United States in the early 1900s, possibly because of low estate taxes, the novelty of extreme wealth, or cultural differences. There are signs of change, however, especially among billionaires who emigrated to countries with a tradition of philanthropy.

Among the most notable is George Soros, a native Hungarian and US citizen who has given an estimated $8 billion toward promoting liberalism, education, and democracy in Eastern Europe. Mo Ibrahim, a British citizen born in Sudan, created the Mo Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership, which offers $5 million to leaders who help their countries escape war, democratize, and prosper. He has also joined the Giving Pledge, a commitment by the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to dedicate the majority of their wealth to philanthropy. Leonard Blavatnik, a US citizen born in the Soviet Union, donated $117 million to Oxford University to establish the Blavatnik School of Government there.

Russia has experienced recent growth in philanthropy. Ruben Vardanian (whose net worth is estimated at $850 million) ran the investment bank Troika for more than a decade before selling it. He now devotes his money and energy to charity, focusing on education, infrastructure, and renovating archeological sites. He does not consider it philanthropy. “Philanthropy usually means you’re giving money and forgetting about it. I am quite actively involved in the management decisions. It’s like capitalism…Keeping all this pressure, being a tough investment banker, but delivering results for charities.”12 His children will inherit only property, no money. According to the Foundation Center, by the end of 2006 wealthy Russians had established more than 20 foundations (Spero 2014). Some of Russia’s biggest philanthropists have preferred to donate outside the country.

China, Brazil, and India have also witnessed a flurry of activity in recent years. Wealth-X reports the top five philanthropist countries in three categories: the most generous, most numerous, and most frequent. The United States tops the list in all three, but China places third on most numerous, India ranks second on most generous (with China fourth), and Singapore comes in third on most frequent (with China fifth). Emerging-market countries take one-third of the spots. The self-made superrich make up a larger share of philanthropists than people who inherited their fortunes. Education is the top philanthropic priority.

Philanthropy is also spreading to smaller countries. The richest man in the Czech Republic, Petr Kellner, supports education, especially of low-income children. His foundation, Open Gate, provides about $5 million a year.

Wealthy foundations tend to have different (sometimes complementary) goals from the government.13 Philanthropy disproportionately targets education, for example, while governments spend relatively more on the social safety net.

In many countries, charities may be more efficiently run than government funds. As Andrew Carnegie claimed, the wealthy are better managers of capital than governments. To the extent that the estate tax deduction encourages philanthropy, it creates more aggregate revenue for charities and government spending combined.

Taxing Unproductive Activities

Another large group of superrich that is of growing concern are financial sector billionaires. Some financial activities are likely to be unproductive from a social standpoint, especially compared with engineering or computer science. Because they offer high returns, they attract top talent.

Studies of the United States find that the most talented individuals are diverted from innovative sectors because of the large personal economic gains associated with the financial sector. Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef (2009) find that the financial sector attracted higher-quality workers in the 1930s and since the 1980s but not in the period when Depression-era banking regulations were in place. Before 1990 the wages of highly educated (postgraduate degree) workers in finance and engineering largely tracked one another; since 1990 wages for highly educated workers in the financial sector have grown much more rapidly than wages of highly educated engineers.

The fact that many of the most talented people are being pulled into finance is worrisome in itself. Luigi Zingales is also concerned about the ability of smart, highly paid financial sector managers to create walls around their earnings. “Thanks to its resources and cleverness, [the financial sector] has increasingly been able to rig the rules to its own advantage,” he notes (Zingales 2012, 49).

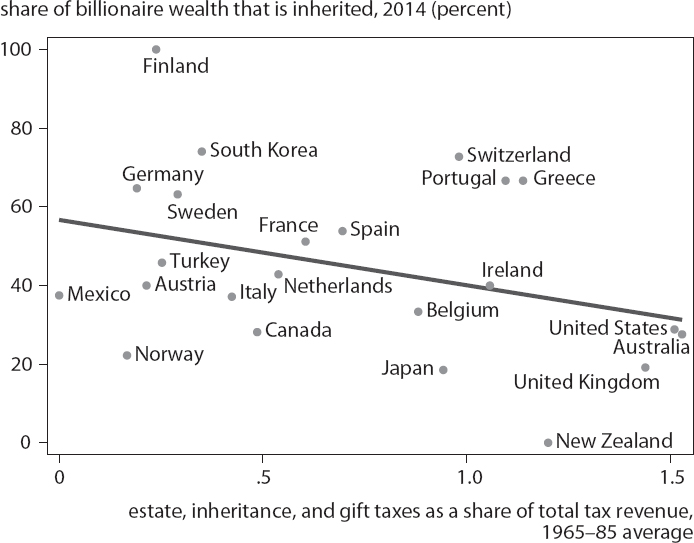

Table 10.1 Sources of wealth of self-made financial-sector billionaires in advanced countries and emerging economies, 2001 and 2014 (percent)

Source: Author’s calculations using data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Dividing financial sector wealth into hedge funds; private equity; venture capital; finance, banking, and insurance; real estate; and investments and other diversified wealth highlights these concerns. Table 10.1 shows the distribution of self-made financial sector billionaires by industry in 2001 and 2014, in the North and South.

In the South, where the share of self-made financial sector wealth declined between 2001 and 2014, the largest share of financial sector billionaires’ wealth (39 percent) is now from real estate. The North shows a more diversified picture, with a sharp increase in the importance of hedge funds and finance at the expense of private equity and venture capital.

The rise in real estate wealth in emerging markets may be indicative of a need for higher real estate taxes, land reform, or more transparent regulation.14 One aim of policy should be to discourage excessive risk taking and ensure transparency in real estate transactions. In the North the rise in hedge fund wealth and the stable fortunes of real estate billionaires following the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression suggests that government policies did not equitably distribute the costs of the crisis to the sector. Following the Asian financial crisis, extreme wealth in the financial sector plummeted; to this day its share remains well below averages in 1996. The fact that the sector’s wealth has grown in the United States since the crisis supports the call for reform of the financial regulatory system.

Takeaways

Many of the superrich help economies grow, create jobs, and spur development. They are often the people who make industrial and technological leaps possible. Ensuring that innovators continue to thrive is good for global growth. In the South the most important policies that can help them do so are establishment of property rights, free entry and exit of firms, and openness to trade and FDI. Ensuring that producers compete in contestable markets is critical.

There is some evidence that industrial policies that assist successful private sector exporters may help countries foster the national champions that promote growth. These policies are distinct from state capitalism (where the state is a direct player in the economy) or industrial policy that focuses on sectoral development. These kinds of policies seek to promote large-scale entrepreneurship by helping resources flow more rapidly to the most productive firms to promote modernization.

Policy can also help contain less productive sources of wealth. In some countries extreme wealth has been concentrated among heirs or in the financial sector. Limiting inheritance and financial sector wealth are best done via estate taxes and financial activity taxes.

1. The importance of property rights in promoting entrepreneurship and commerce is well known. It is therefore discussed here only briefly.

2. For example, the Economist’s Big Mac index measures the relative cost of a Big Mac in different countries. When the index diverges significantly in countries at similar stages of development, the home currency of the more expensive hamburger is very likely overvalued.

3. Intel closed its Costa Rican factory in 2014 and moved its operations to Malaysia.

4. Alec Luhn, “Not Just Oil and Oligarchs,” Slate Magazine, December 9, 2013.

5. Christiana Sciaudone, “Embraer Seen Winning Regional-Jet Contest with Bombardier,” Bloomberg Business, November 7, 2013.

6. Russ Mitchell, “The Little Aircraft Company That Could,” Fortune, November 15, 2005.

7. Some firms from developing countries have tried to tap financial markets abroad, mainly through listings on the New York, London, or Hong Kong exchanges. But these firms are already very large, and they are typically energy companies or other resource-oriented concerns, or in communications or financial services, such as telecom or banks.

8. Estate taxes are applied to the combined estate of the deceased. Inheritance taxes are applied to each recipient’s portion. Estate taxes are typically coupled with gift taxes, in order to ensure that the transfer of assets before death is treated the same way as the transfer after death.

9. The United States spent $15.5 billion on food stamps in 2001 and $71.8 billion 2011 (“Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs,” US Department of Agriculture, August 7, 2015, www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/pd/SNAPsummary.pdf).

10. Most states charged estate taxes even during the period of appeal.

11. See West (1980) for a history of inheritance and estate taxes.

12. “Ruben Vardanian, Former Troika Dialog CEO: A Grumbling Optimist,” The Monday Interview, Financial Times, January 4, 2015.

13. The rich tend to have different preferences from the average person (opera, museums, exotic butterfly collections), which their charitable causes disproportionately support. In principle, the government could offer a sliding scale for the deductibility for such gifts, but doing so could be difficult to achieve in practice.

14. The real estate sector has been intricately linked with financial sector problems in both advanced countries and emerging markets. Real estate speculation is a common source of costly bubbles. Concerns about real estate also include the nature of real estate transactions in some countries, such as China, where current ownership (or long-term leasing) requires government licenses and is thus susceptible to political rents.