IN THE PRECEDING chapters, I have focused on the requirements for effective business strategy, a key element of which is meaningful product differentiation. But any consideration of the positioning of products in the marketplace must also include the impact of branding on consumer choice. I will discuss the role of branding in business strategy in the next two chapters.

Strong brands are the physical and emotional embodiments of successful business strategy. Customers reward strong brands with enduring loyalty, often at premium prices, and by serving as brand evangelists, which can bolster a company’s financial performance for years. Strong brands are perceived to not only deliver superior product performance or value but also evoke a deeper emotional response, underscoring how consumers feel about their experience with the brand.

At the other end of the spectrum, ask any group of consumers to identify their least favorite brands and the conversation is likely to turn lively and salty. Brands are powerful forces in the marketplace.

To introduce this topic, in my first class each semester, I often ask my MBA students to identify their favorite brand and to explain the reasons for its appeal. The responses span a wide range of products, from quotidian consumables to aspirational luxuries. Figure 7.1 displays a sample from a recent class, organized by category.

Figure 7.1 MBA student favorite brands. Does not represent endorsement by pictured companies. Logos © Nike, Inc.; Unilever; Equinox Fitness; Clinique Laboratories, LLC; SoulCycle; Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin; Rent the Runway; Fresh Direct, LLC; Papyrus, Schurman Retail Group; Kayak.com, The Priceline Group; Louis Vuitton Malletier; BMW AG; Trader Joe’s; Zara, Inditex Group; Inter IKEA Systems BV; Apple, Inc.; The Emirates Group; Toyota Motor Sales, Inc.

What this diverse array of favored brands has in common is a deep customer connection, described in the adulatory comments shown in the box (see page 141). Competitors would be hard-pressed to gain favor among my students, whose favorite brands evoke fond memories of childhood (Nutella), provide a conduit to express personal feelings (Papyrus), or go beyond mere utility and into the realm of desire (Louis Vuitton). Such consumer sentiments are the hallmarks of exceptionally strong brands.

The Meaning of a Brand

A logical starting point for the exploration of brand dynamics is to identify the critical characteristics required to build and maintain a strong affinity with consumers. Strong brands deliver a promise, convey mutual trust, and reinforce a consumer’s symbolic identity.

Brand Promise

A brand promise clearly communicates what a company’s products stand for. Every brand identified in figure 7.1 delivers a strong brand promise, whether it is “ultimate driving machines” from BMW, adventurous, great-tasting, and affordable foods from Trader Joe’s, or exquisitely designed lifestyle-enhancing technologies from Apple. A brand’s promise is defined not only by how a product is expected to perform but also by how it makes a user feel.

Representative Reasons for Brand Affinity

Nutella

“I have been eating Nutella since I was a very young child. It has always meant to me both a memory of my childhood and a fundamental component of my breakfast before doing sports activities. Despite having tried many other chocolate spreads, both commercial and artisan/homemade, I would always choose Nutella above all of them.”

SoulCycle

“I have become habituated to logging on to the website on Mondays at noon when the class schedule opens for the week to be among the first to book. Even though every week the website freezes at that time and I feel frustrated, I continue to sign up and go to the classes because I do not think there is another workout, or even cycling class, that delivers that same mix of challenge and fun.”

Rogue Fitness

“Rogue’s equipment is perfectly suited to the type of workout I do and their brand is aggressive and in-your-face, which appeals to my personality. The colors on their equipment, website, and marketing are suited to people of like sensibilities and reinforce their aggressive branding (black and red). Rogue has stayed consistent with this branding and continually released more and more desirable equipment to keep my engagement with my hobby fresh and exciting.”

Emirates

“Emirates provides an in-flight experience that is very different to any other airline. The food is amazing, the planes are always new and clean, and the staff attentive and thoughtful. I will always pay a premium for this service. My experience with Emirates is also associated with traveling to fun holidays and exciting new adventures, which adds to the brand’s appeal.”

Papyrus

“Papyrus is my favorite place to buy greeting cards. They are in convenient locations around the city and I am always able to find the perfect card for a special occasion. Though cards are more expensive than a typical greeting card, often twice as much, I think cards are a really great way to express my feelings and add a personal touch to make something more memorable. The thoughtfulness that can be expressed in the perfect card is worth paying extra for.”

Louis Vuitton

“One of my favorite brands is Louis Vuitton. I truly admire brands that are able to tell a story and deliver a transporting, emotional experience to their audience, and Louis Vuitton does this masterfully on its website, in its ‘maisons’ and through runway shows, museum exhibitions, and creative collaborations that celebrate the art of travel and of living, eliciting in the consumer a need that goes beyond mere utility and into the realm of desire.”

From a consumer’s perspective, a strong brand promise reduces the cognitive strain to understand the detailed attributes of complex products or the need to analyze competing and confusing advertising claims. For example, BMW loyalists need not concern themselves (unless they want to) with the technical wizardry underlying BMW’s full-color heads-up displays, Valvetronic engines, or aluminum crankshaft designs, provided that they perceive overall that the brand continues to deliver an “ultimate driving experience.” From a company’s perspective, a strong brand promise represents a critically important corporate asset, contributing lasting value beyond the lifespan of any given product. Several respected independent assessments have estimated the value of top-performing global brands to be in excess of $100 billion.1 Strong brands serve customers and companies extremely well.

Maintaining a strong brand promise requires creative and disciplined product development coupled with effective marketing communications to reinforce a clear consumer value proposition. In this regard, it is illustrative to contrast Apple’s approach to archrival Samsung in the consumer electronics space.

Neither Apple nor Samsung use a signature tagline like BMW’s “The Ultimate Driving Machine” to define their brand promise. So consumers have to form their own impressions from the timing and types of products released, and how each company chooses to communicate its brand story.

Apple is widely considered to be among the most valuable brands in the world.2 How would you articulate Apple’s brand promise? When I’ve asked my MBA students this question, their responses can be synthesized as follows.

Apple creates beautiful, technologically advanced, easy-to-use products that enrich my life and help me express myself.

Students are a bit less certain about Samsung’s brand character. What emerges from class discussion is as much shaped by the negative feelings some students harbor toward Apple as it is by distinguishing positive attributes of Samsung’s brand per se. The following statement best captures how my students describe Samsung’s brand promise.

Samsung creates first-to-market, cutting-edge products at competitive prices that allow me to organize my life around Google apps.

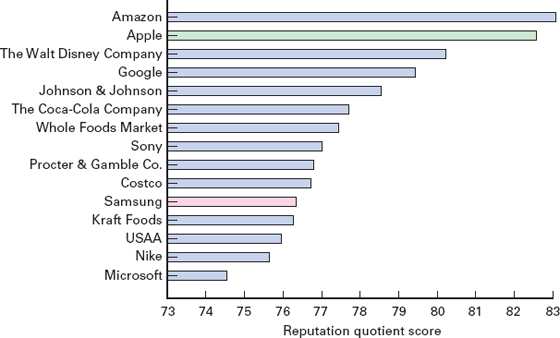

Apple clearly evokes a deeper, more emotive bond with its brand enthusiasts than Samsung, whose customers tend to express more technical respect than love for the brand. Broader market research from a Harris Interactive consumer survey confirms that Apple enjoys a considerable advantage over Samsung in image strength (figure 7.2).3

Figure 7.2 Brand image strength

As a testament to how clearly a strong brand promise can be understood in the marketplace, consider the print advertisements depicted in figure 7.3, which reinforce the value propositions of Axe body sprays and Federal Express without the need for any explanatory text.4 You may not be a hormonal male teenager or in need of shipping a package from London to Barcelona, but there should be little doubt about the brand promise of either of these companies. A clear, consistent, and relevant value proposition lies at the heart of companies that succeed in delivering a strong brand promise over the long term.

Figure 7.3 Wordless print ads for Axe (top) and FedEx (bottom). © Axe Body Spray, Unilever, and © FedEx Corporation. All rights reserved.

Mutual Trust

Brands that build a strong bond with customers enjoy a symbiotic relationship of mutual trust. Consumers trust their favored brands to consistently deliver appealing products and are likely to maintain loyalty—as long as their expectations are met. On the other hand, companies need to trust that their targeted customers will remain loyal as long as they continue to deliver on their brand promise. This implies the need for strong brand discipline to avoid racing to market with immature products of dubious value, getting caught in a “feature–function arms race” against competing brands, which overshoots the real needs of market, or introducing dissonant product-line extensions that dilute brand equity.

As an illustrative example, perhaps the most celebrated case of a company breaking its mutual trust with customers was the 1985 launch of New Coke.5 Coca-Cola’s iconic brand had long dominated the U.S. market for carbonated soft drinks, peaking at over 60 percent of the market shortly after World War II. However, archrival PepsiCo began gaining share with its pleasingly sweeter-tasting cola, promoted heavily to younger consumers in the long-running “Pepsi Generation” advertising campaign.6 By the early 1980s, Coca-Cola’s market share had shrunk to 24 percent and Pepsi was actually outselling Coke in supermarket chains.7

Alarmed by Pepsi’s market gains, and by its own blind-taste tests that showed that a majority of consumers preferred the taste of Pepsi, Coca-Cola CEO Roberto Goizueta ordered a product development team to develop an improved version of Coke’s century-old secret formula. The team eventually settled on a sweeter-tasting cola that consistently beat both regular Coke and Pepsi in blind-taste tests. Extensive market research confirmed consumer preference for what came to be known as New Coke, although the company did detect a vocal minority (10–15 percent) of focus group participants who viscerally opposed the prospect of tampering with Coca-Cola’s trusted brand.

Coca-Cola announced the launch of New Coke with great fanfare on April 19, 1985, and ceased production of its original formulation the same week. Despite encouraging initial sales of the new product, hundreds of thousands of angry letters and phone calls poured into Coca-Cola’s Atlanta headquarters, amplified by widespread press coverage of public protests in southern U.S. cities depicting dissatisfied consumers emptying cans of New Coke into the streets. Company executives became concerned as the sales of New Coke slowed, and U.S. bottlers and overseas divisions began expressing growing anxiety over adverse market reactions.

After just seventy-nine days, Coca-Cola altered course, and re-introduced its original product, now called Coke Classic, alongside New Coke. The company promoted the return of Coke Classic with advertisements touting the brand’s heritage and traditional values, accompanied by nostalgic images reminiscent of Norman Rockwell paintings. Consumers responded by flooding corporate headquarters with thankful letters and calls, prompting one executive to remark “you would have thought we’d cured cancer.”8

Coca-Cola sales immediately soared, and by the end of the 1985, Coke Classic was substantially outselling both New Coke and Pepsi. By the following spring, the market share of New Coke had slipped to only 3 percent, despite having outspent Coke Classic on advertising since its launch.9 Coke Classic continued to build on its market leadership, and in 2002, Coca-Cola quietly discontinued New Coke (then called Coke II) and dropped “Classic” from the name of its iconic soda.

In retrospect, Coca-Cola concluded that it had profoundly underestimated the backlash from a vocal segment of its customer base whose trust in the company was broken by the new product substitution. Ironically, years after its failed launch, blind-taste tests continued to confirm that New Coke was preferred over Pepsi and Coke Classic. But as Coca-Cola found, it had built an exceptionally strong bond with its customers, rooted in intangible brand associations with tradition, legacy, and trust.

When Coca-Cola broke its mutual trust with consumers, abandoning its proud heritage in search of new customers, it triggered a rebellion that resonated with a large segment of the market. As it turned out, by quickly learning from its mistake and responding to consumer sentiment, Coca-Cola emerged stronger than ever in the ongoing cola wars with PepsiCo. This infamous case clearly illustrates the importance of mutual trust in building and nurturing a strong brand.

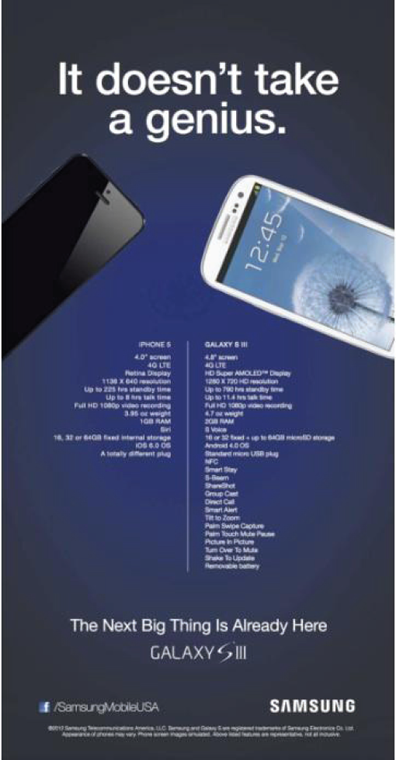

To illustrate a more recent example of how mutual trust can strengthen consumer affinity to a brand, let’s return to the competition between Apple and Samsung. By most objective measures, Samsung should be faring better in the consumer electronics market. After all, true to its brand promise, Samsung did beat Apple to market with larger smartphones, higher-resolution cameras and screens, and high-tech features like bump-to-share file transfer, all at lower average selling prices than Apple. Samsung also launched its first Galaxy Gear smart watch more than eighteen months before Apple’s initial entry into this category. To tout these achievements, Samsung has heavily marketed its technical prowess and speed, considerably outspending Apple on global advertising and promotion. For example, figure 7.4 displays a 2012 Samsung Galaxy S III smartphone print advertisement touting its far longer list of technical features than Apple’s comparable (and, at the time, yet to be introduced) iPhone 5.10

Figure 7.4 Samsung “It Doesn’t Take a Genius,” print advertisement, 2012. © Samsung Electronics. All rights reserved.

Nonetheless, Samsung has been losing global market share over the past three years (at the time of this writing), and Apple outsold Samsung’s smartphones in the two largest markets—the United States and China— in the first quarter of 2015.11 Moreover, in 2015, Apple’s mobile devices earned more than seven times the operating income of Samsung, accounting for a market-dominating 91 percent of total industry profits.12

The reason is that Apple’s brand promise delivers more meaningfully differentiated value to a large class of customers who are willing to wait for—and have a far higher willingness to pay for—what is perceived to be the most elegant and sophisticated product designs on the market. Rather than promote a long list of technical product features, Apple’s marketing communications consistently reinforce how its iPhones enrich the lives of its customers.

To be sure, there are customers who will always want to be the first to own the latest high-tech products. But Apple is not interested in serving the early-adopter segment, or, for that matter, budget-conscious consumers, focusing instead on the far more lucrative segment of consumers with patience and the willingness to pay for highly sophisticated and refined product designs.

Despite its reputation for innovation, Apple actually has a long history of not being the first mover in any of the consumer electronics categories it has entered and dominated over the past two decades (see figure 4.6). As such, Apple has demonstrated admirable discipline as a brand leader, building mutual trust in two important respects.

First, strong brands define themselves as much by what they won’t do as by what they will do. Apple has resisted the temptation to rush new products to market to match competitors on new technical features. Rather, the company takes the time required to refine the overall user experience and perceived value before releasing a new product.

Second, strong brands define themselves as much by the consumers they don’t target as those they do. Apple has ignored critics who have strongly urged the company to launch budget-priced models to extend its penetration in rapidly growing Asian markets. Instead, Apple has remained true to its historical practice of exclusively serving the premium end of the consumer electronics market

As a result, Apple and its customers have developed a strong mutual trust that has served both sides exceptionally well.

Symbolic Identity

For many consumers, the purchase or ownership of a brand signals membership in a desired social grouping. This is particularly true in categories where tangible product differences are difficult to discern, yet consumers still express fierce loyalty to brands perceived to reinforce their values and social standing. In short, many consumers strongly prefer brands that appeal to “people just like me.”

Brand managers recognize the importance of symbolic identity and often focus advertising themes on lifestyle images rather than tangible product attributes. Some of the most successful and iconic advertising campaigns of all time—including the “Marlboro Man,” the “Pepsi Generation,” and L’Oréal’s “Because You’re Worth It”—are rooted in the exploitation of symbolic identity.

To illustrate the importance of symbolic identity in brand development, consider the extraordinary case of Pabst Blue Ribbon (PBR) beer. The beer category presents an interesting challenge to marketers because most consumers are unable to identify their preferred brand in blind-taste tastes. Thus, symbolic identity associated with beer brands plays a pivotal role in consumer choice.13

Pabst Blue Ribbon is a 125-year-old brand that peaked in the late 1970s as the third-best-selling beer in the United States, with sales of over twenty million barrels. But adverse U.S. beer consumption trends and internal management turmoil took its toll on PBR, and sales declined for twenty-three consecutive years to less than one million barrels in 2001.14

Customers of PBR skewed toward lower-income, older men clinging to a venerable beer brand sold at a budget price. Pabst sought to harvest what remained of its dwindling market by cutting costs, contracting out production, and eliminating brand advertising.

But then a curious thing happened. For reasons that are murky at best, PBR sales began taking off in northwestern states. The company sent a marketing team to investigate and discovered that PBR had become the brand of choice for young hipsters—e.g., bike messengers in Portland and snowboarders in Idaho. These countercultural consumers preferred the least pretentious, most unglamorous beer they could find, expressing their rebellious symbolic identity. The fact that Pabst could not afford to advertise proved to be a blessing in disguise for these unanticipated new fans.

It is important to note that PBR’s new brand image and popularity was created by consumers, not company marketers. Countercultural consumers self-identified with a decidedly non-mainstream brand.

Once Pabst understood the basis of PBR’s growing appeal, the company worked in the background to fuel the flames of symbolic identity, sponsoring small, local tournaments that would be popular with young hipsters (e.g., for skateboarding and bike polo), but never “going corporate” with TV commercials or major event sponsorships like the X Games. Pabst also paid for product placements to associate the brand with offbeat, tough guys like Clint Eastwood in the movie Gran Torino and Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet.

With word-of-mouth referrals going viral, PBR sales grew by double-digit percentages through the 2000s, exceeding six million barrels by 2008. While PBR’s case is perhaps an extreme example of the importance of symbolic identity to a brand’s persona, all companies should be conscious of the opportunity to nurture an emotional bond with their core consumers.

A more recent example of a company that built a powerful brand by focusing on symbolic identity is Dove—a personal-care products division of Unilever. While Dove has long enjoyed market-share leadership in bar soap, the signature product that launched the brand in 1957, Dove struggled to achieve similar success with its subsequent entries in the personal-care category, including deodorants, lotions, and hair-care products.

Rather than try to take on industry leader Procter & Gamble and other leading personal-care brands in an expensive marketing campaign focused on product attributes, Dove recognized the opportunity to create a strong bond with consumers by initiating a global dialogue on a healthier and more holistic view of the meaning of female beauty.

The Dove Campaign for Real Beauty was conceived in 2004 after market research revealed that only 4 percent of women consider themselves beautiful. The mission of Dove’s Real Beauty campaign was “to create a world where beauty is a source of confidence and not anxiety.”15

To implement the campaign, Dove used billboards, print advertising, social media, YouTube videos, and television commercials, all with the unifying theme of celebrating the beauty of women of all ages, shapes, and sizes (figure 7.5).16

Figure 7.5 Print ads for Dove’s Real Beauty campaign. © Dove Beauty, Unilever. All rights reserved.

In 2013, Dove produced a six-minute video posted on its YouTube channel to extend its Real Beauty campaign.17 In the video, several women portray themselves to a hidden forensic artist, who sketches their face to match their self-image. The same artist then sketches the women again, this time using the descriptions provided by strangers who met the subjects the previous day (figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6 Still from Dove’s “Sketches” commercial. © Dove Beauty, Unilever. All rights reserved.

The sketches are then compared, with the stranger’s image invariably being both more flattering and more accurate, evoking a visceral and highly emotional reaction when shown to the subjects of the experiment. The “Sketches” campaign created a viral sensation, and went on to become the most-watched YouTube advertisement in history, reaching more than 200 million global viewers.18

Dove’s Real Beauty campaign succeeded in tapping into an issue of widespread concern to women. What made the campaign successful is that women of all ages and cultural backgrounds could symbolically identify with the message that Dove was promoting. As such, Dove’s products became associated with a positive brand image, which has helped the company increase its global market share.19 For example, between 2008 and 2014, while Procter & Gamble’s personal-care product sales were flat, Unilever’s sales over the same period grew by 56 percent.20

Connecting the Dots: Business Strategy Drives Brand Strategy

As all the examples in this chapter illustrate, strong brands rest on a foundation of a clear brand promise, mutual trust, and a symbolic identity that resonates strongly with consumers. Companies that nurture and strengthen their brands over time can earn attractive returns on a valuable asset and achieve enduring competitive resilience. Companies should focus on building and nurturing strong brands as if their corporate lives depended on it, because it often does.

In chapter 1, I made the case that there are three strategic imperatives to drive sustained profitable corporate growth:

1. Continuous innovation—not for its own sake, but to deliver….

2. Meaningful differentiation—recognized and valued by consumers, enabled by…

3. Business alignment—where all corporate capabilities, resources, incentives, and business culture and processes are aligned to support a company’s strategic intent.

We now are in a position to make the logical connection between the requirements for effective business strategy and brand strategy. As shown in figure 7.7, companies that continuously innovate to deliver meaningfully differentiated products and services can reinforce their brand promise, sustain mutual trust, and strengthen the symbolic identity that consumers associate with the brand. These mutually reinforcing elements of effective business and brand strategy provide the basis to attract and retain customers and create competitive resilience. If all of these strategy elements are in place, companies are well positioned to achieve the holy grail of business: long-term profitable growth.

Figure 7.7 Link between business and brand strategy