BY NOW, I have made the case that sustained, profitable growth requires continuous innovation to deliver meaningful differentiation, most evidently in products that break away from traditional bases of competition to create entirely new consumer value propositions. But where do great ideas come from? And what tools and techniques can companies use to systematically identify and develop breakthrough product opportunities?

In simple terms, the genesis of all breakthrough products is an innovator’s recognition of a better way for consumers or businesses to perform desired tasks. In some cases, successful new products fix a “pain point” associated with using current market offerings to perform routine jobs. This was certainly the case with Swiffer, for example. Launched by Procter & Gamble in the late 1990s, Swiffer proved the dry mop was far more convenient than traditional wet mop cleaning products, including the company’s own Mr. Clean brand. The fact that Swiffer replacement pads carry a higher price and margin than traditional liquid household cleaners made this product a win-win solution for consumers and the company alike. Procter & Gamble followed the same playbook when it launched Tide Pods—a single-dose version of its liquid and powder detergents—which reinforced the company’s dominance of the laundry detergent market.

In other cases, enlightened entrepreneurs envision products, such as GoPro video cameras, Facebook, and Post-it Notes, that tap latent needs many consumers may not even have realized they had. In 2002, Nick Woodman, an adventure-sports enthusiast, jury-rigged a crude strap-on camera after being unable to find a product on the market that could capture still images of his surfing adventures. Fellow surfers responded enthusiastically to the new product, prompting Woodman to extend his concept to digital video cameras. GoPro cameras unlocked a huge untapped demand among consumers seeking to capture images of their sporting adventures. By solving his own consumer need, Woodman laid the groundwork to build GoPro Inc. into a profitable, growing enterprise with a multi-billion dollar market value.1

There are two ways to discover new products. Most often, an entrepreneur like Woodman identifies a specific pain point or new value-creation opportunity, and seeks to develop a novel solution to the problem. But there are also notable examples where an entrepreneur starts by serendipitously identifying a novel solution, and then searches for a relevant problem to solve.

Take, for example, the inspiring story of Jorge Odón, an Argentine car mechanic, who developed a novel device to assist in difficult birth situations. In 2006, Odón watched a YouTube video demonstrating how to remove a cork stuck inside a glass bottle using nothing more than a plastic bag. During a night out with friends (who had not seen the video), Odón won a dinner bet that he could perform the seemingly impossible feat. Later that night, Odón—a father of five children, with no medical training—found himself dreaming of how the same parlor trick might be adapted to save a baby stuck in the birth canal. At 4:00 a.m., he woke his wife to tell her the idea that had just come to him. His wife, he recalled, “said I was crazy and went back to sleep.”2

The problem Odón found himself dreaming about—literally and figuratively—is very real. Ninety-nine percent of mothers who die during childbirth live in countries where doctors lack access to the training and tools to assist in difficult deliveries.3 Odón persisted in following his dream of creating a simple lifesaving device, building a prototype in his kitchen using a glass jar for a womb, his daughter’s doll for the trapped baby, and a fabric bag and sleeve sewn by his wife.

With the help of family members, Odón arranged a meeting with the chief of obstetrics at a major teaching hospital in Buenos Aires to demonstrate his prototype. Impressed, the chief helped Odón apply for patents and connected him with officials of the World Health Organization, who eventually embraced the solution. By 2011, Odón’s patented solution had been used in thirty successful live trials. In 2014, Odón quit his automobile-repair job to work full time on his invention. Meanwhile, research continues around the globe toward perfecting the Odón device.

Another example of a solution looking for the right problem can be found in the circuitous path taken in the development of Post-it Notes. In 1968, 3M research scientist Spencer Silver was working on the development of industrial-strength adhesives intended for use in the aerospace industry. Instead of a creating a superstrong glue, Silver stumbled upon an incredibly weak, pressure-sensitive adhesive called acrylate copolymer microspheres (ACM). His new adhesive had two interesting properties: first, when applied to a surface, ACM could be peeled away without leaving any residue; and second, the adhesive was reusable.

However, no one at 3M, including Silver himself, could envision how to exploit these distinctive properties in a marketable product. The best idea that emerged from early brainstorming was for a coated bulletin board, to which plain paper notes could be attached. However, this hardly seemed likely to be a game-changing new business idea. Although Silver continued to proselytize the merits of his unusual discovery within the company, further work on ACM was shelved for five years.

In 1973, a serendipitous event brought what was to become Post-it Notes back to life. Over lunch in the 3M cafeteria one day, a product-development engineer named Art Fry shared with Silver a chronic problem he was experiencing: his hymnal bookmarks kept falling out during church choir practice. Familiar with Silver’s discovery from prior company meetings, Fry asked if he could use some of the reusable adhesive to keep his bookmarks in place. Extending the thought further, Fry shared his opinion that 3M had probably been thinking backward about potential ACM product applications. Instead of coating a bulletin board with the reusable adhesive, Fry argued that 3M should apply the adhesive to paper notes, which could then stick to anything. “I thought, what we have here isn’t just a bookmark,” said Fry. “It’s a whole new way to communicate.”4

To pursue Fry’s innovative insight, 3M required further R&D to ensure that the adhesive would only stick to a treated paper note and not to any other surface to which it was applied. With renewed interest in his discovery, Silver and his team were soon able to perfect a reliable formula for ACM that enabled the creation of Post-it Notes.

Despite what now appeared to be a promising new product with the potential for broad market appeal, 3M management remained reluctant to commit to commercial development. After all, producing Post-it Notes at a larger scale would require a sizeable capital outlay for what was still considered to be an unproven concept. To build support, Silver and his team set up a “skunk works” to create batches of Post-it Notes that he shared with 3M employees. This stealthy undertaking had the benefit of providing valuable consumer feedback, as well as building internal support for further project funding. Backed by enthusiastic 3M employee testimonials, Silver and his colleagues were finally able to secure management approval in 1977 to launch a pilot test in four cities of what were then called “Press ’n’ Peel” sticky notes.5

Unfortunately, the initial pilot tests turned out to be a dismal failure. The company provided relatively little marketing support for the pilot tests, and consumers simply didn’t understand or appreciate the value proposition associated with sticky notes. Press ’n’ Peel languished on retailer shelves.

Despite this setback, promoters of the new product were determined to give Post-it Notes another chance, this time with more marketing support. So, one year after the initial flop, 3M launched a second pilot test in Boise, Idaho, giving away batches of Post-it Notes so consumers could experience for themselves how useful the new product could be. This time, 3M’s reorder rate went from almost zero in the previous pilot to 90 percent, double the best market acceptance rate 3M had ever experienced in a product pilot test.

Two years later, in 1980, Post-it Notes were officially launched nationally and the business has grown steadily ever since. Post-it Notes are currently sold in over four thousand product varieties in more than 150 countries, generating revenues of over half a billion dollars for 3M.6

In retrospect, the successes of Post-it Notes, GoPro, and Swiffer seem like slam dunks, given that each delivered a simple and compelling consumer value proposition. The same could be said of Airbnb, conceived by Brian Chesky, a struggling, unemployed industrial designer living in San Francisco, who parlayed the need to rent out a spare bedroom to help pay his rent into one of Silicon Valley’s most successful recent ventures.7 Or Spanx, launched by Sara Blakely, a fax-machine salesperson without any background in fashion, marketing, or retailing, who designed a comfortable shaping undergarment for women, after struggling for years with unflattering and ill-fitting products on the market.8

The question remains, where do these breakthrough ideas come from? Does one have to have the rare entrepreneurial instincts found only in geniuses like Chesky, Odón, Woodman, Fry, or Blakely to conjure up winning products? Or can mere mortals working on their own or within a major corporation hope to develop breakthrough products? Extensive research has identified the brain functions that enable the creative spark—or strategic intuition—that allow innovators to imagine breakthrough products and services.9 While genius undoubtedly helps, any aspiring entrepreneur with intellectual curiosity, open-mindedness, customer empathy and the passion and perseverance to solve problems can come up with game-changing product concepts.

There are two foundational skills underlying successful innovation:

• Behavioral insight, driven by consumer empathy The ability to deeply understand consumer behavior, enabling the diagnosis of current pain points or the identification of latent consumer needs.

• Creative problem-solving ability The ability to translate behavioral insights into products specifically designed to better serve consumer needs and desires.

The examples I have cited may lead one to conclude that most breakthrough ideas are conceived in a lightning bolt of inspiration, in which an innovator instantaneously envisions a novel product solution to a vexing consumer problem. This view has been reinforced by brilliant innovators like Henry Ford and Steve Jobs, who dismissed the need for market research to guide their innovative thinking. For example, Henry Ford is believed to have once quipped, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”10 And Steve Jobs echoed similar sentiments, noting that “people don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research.”11

Are we to believe that innovators operate in their own creative bubble, without the need to interact with prospective customers? Nothing could be further from the truth. An entrepreneur’s inspiration for an innovative new product reflects nothing more than an initial hypothesis and hunch, borne out of personal experience and observation. This, in turn, requires considerable additional vetting with prospective consumers to validate assumed marketplace behavior and to iteratively optimize final product designs.

Ask any successful entrepreneur to compare his or her initial concept for a breakthrough product with the final version that ultimately achieved strong market acceptance and, invariably, you’ll find a considerable product evolution, reflecting the reality that no “business plan ever survives its first encounter with a customer.”12 For example, Pinterest, currently valued at over $10 billion, started in 2009 as Tote, a mobile-shopping app with tools that allowed customers to window-shop and store wish-list items on their smartphone. Tote hit the market a bit too soon to achieve success as a mobile-shopping app. However, founder Ben Silbermann observed how Tote users enjoyed amassing and sharing collections of wish-list items, sparking the pivot from Tote to Pinterest in 2010. Other examples of notable business pivots that evolved from ongoing customer feedback include Flickr, which started as a photo-sharing feature within an unsuccessful multi-player computer game, and YouTube, which started as a video dating site, before expanding into the largest video-sharing platform in the world.

Why Consumers Often Lead Companies Astray

How can we reconcile two opposing views on the genesis of great ideas: a lightning bolt of creativity or the result of carefully assessing and responding to marketplace needs? In reality, the comments of Henry Ford and Steve Jobs on this question reflect how and when consumer feedback should be used during the product development process, and not whether market research per se has merit. They were correct in recognizing that most consumers generally lack the diagnostic and problem-solving skills required to envision breakthrough product opportunities. As a result, there is little to be gained by using traditional market-research techniques such as focus groups or surveys to troll for new product ideas.

To see why traditional market-research techniques are often ineffective and likely to be misleading in identifying breakthrough product opportunities, consider the following simple example. In a recent MBA class, I asked my students to share their ideas for the design of an innovative measuring cup. Now, this may seem like an unusually prosaic product to waste creative energy on, but remember the everyday floor mop that led to Swiffer, Procter & Gamble’s billion-dollar brand.

To get the simulated market-research approach started, I asked one hundred of my MBA students to write responses to two simple questions regarding their personal experience using (or seeing others use) measuring cups:

1. What’s wrong with the current design of widely used two-cup glass measuring cups? Specifically, are there any inconveniences or pain points associated with using current products?

2. What features or changes would you like to see in measuring-cup design that would better serve your needs?

These are typical “pains and gains” questions, often asked in focus-group research to uncover new product ideas.

There was no shortage of interesting ideas in response to these questions, and, as noted by the representative answers shown in table 10.1, my students identified numerous current product deficiencies and proposed many solutions.

TABLE 10.1

Measuring Cup Design Ideas

| Identified Problem |

Proposed Solution |

| Hard to read quantities on side of measuring cup. |

Use bigger fonts in labeling measurement scale. |

| Danger of breakage if dropped. |

Use plastic instead of glass. |

| Handle gets slippery when using oily ingredients. |

Add rubber sleeve on handle. |

| Inconvenient when measuring widely different quantities in single size measuring cup. |

Create collapsible product design, where measuring cup can be adjusted to different capacities depending on ingredient quantity required. |

| Cooking ingredients stick to side of measuring cup; awkward to pour ingredients into mixing bowl. |

Add “trap door” bottom that would better release ingredients. |

It is logical to expect that consumers are better at diagnosing current pain points than in proposing innovative solutions. After all, breakthrough product concepts may require new technologies or design innovations that are far beyond the knowledge or experience of average consumers. But surprisingly, consumers are also quite unreliable when responding to simple questions about their pain points associated with using everyday products.

Why is this? The answer is perhaps best explained by Harvard Business School faculty members Dorothy Leonard and Jeffrey Rayport, who noted that “habit tends to inure us to inconvenience; as consumers, we create ‘work-arounds’ that become so familiar we may forget that we are being forced to behave in a less-than-optimal fashion and thus we may be incapable of telling market researchers what we really want.”13

To illustrate this point, at the conclusion of my MBA class discussion on measuring-cup design, I chose two students at random to participate in a simple product-use demonstration.14 Each student—one male and one female—was asked to show the class how they would go about actually using a standard two-cup Pyrex measuring cup for a cake recipe calling for one cup of water. I advised the students that the recipe cautioned about being precise with the measurement, to ensure the best taste results. For the purpose of the demonstration, I placed a large pitcher of water and a standard two-cup Pyrex measuring cup on a classroom desk, representing a kitchen counter.

The first volunteer—a particularly tall male—carefully poured what he thought to be the correct quantity of water from the pitcher, then bent to examine the measuring cup at eye level. Evidently, he had added too much water on his first attempt, and so poured some of the water back into the pitcher. The student volunteer once again bent over to examine the results, only to conclude that he had been too aggressive. This process of pour-bend-examine-adjust was repeated four times before the student was satisfied that he had accurately met the requirements of the recipe.

Next, I had the female volunteer repeat the same demonstration, which took only three cycles to complete, either because she was shorter or simply because she was more adept at using a measuring cup.

At this point, I asked my class of nearly a hundred students whether anyone had observed an apparent shortcoming with the design of a traditional measuring cup that perhaps had escaped our notice during the preceding class discussion. After a considerable pause, one student tentatively raised her hand to suggest, “Maybe it’s the need to repeatedly have to bend down to check the quantity level.” Bingo!

The remarkable thing here is that when initially asked to cite measuring-cup design shortcomings from their own prior experience, not one of my hundred students mentioned the ungainly pour-bend-examine-adjust cycle. In keeping with Leonard and Rayport’s insight, my students had become so inured to a belief that “that’s just the way measuring cups work,” that none bothered to mention an awkward design constraint. But when given the opportunity to observe and reflect on a demonstration of actual consumer product use, the previously hidden pain point became readily apparent.

This is an important revelation. Unless an innovator accurately understands the relevant shortcomings associated with current products, it’s unlikely that he or she can devise an effective solution. Since consumers are often unable to recognize and articulate their own product pain points, careful observation of actual consumer product use is a more effective diagnostic tool than asking consumers directly for behavioral insights on product design.

In fact, my classroom exercise replicated the actual product-design approach used by OXO, a New York–based manufacturer of easy-to-use kitchen appliances and housewares. A few years ago, a small toy company submitted a concept for a new measuring-cup design for OXO’s consideration as a marketable product. The unusually designed measuring cup featured a horseshoe-shaped plastic insert, imprinted with a graded quantity scale. Because of the steep angle of the horseshoe insert, a standing user could easily read the quantity of ingredients while looking down on the measuring cup (figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 Angled measuring cup design

To validate that the novel product actually solved a real consumer problem, OXO used observational research techniques.15

One at a time, respondents from a panel of test subjects were asked to describe any shortcomings they perceived with current measuring cups. Next, each respondent was asked to demonstrate how they would use a conventional measuring cup in a simulated kitchen environment. Finally, respondents were asked to repeat the product demonstration, this time using the new measuring cup with the angled insert.

As in my class exercise, consumers initially failed to identify the critical measuring-cup design shortcoming, despite exhibiting repeated pour-bend-examine-adjust cycles in their product demonstration trials. Nonetheless, respondents instantly “got it” when asked to try out the new product and enthusiastically endorsed the design concept. Armed with these research results, OXO went on to successfully market a new product line of angled measuring cups.16 As OXO found, consumers can show you, if not necessarily tell you, where opportunities for innovative new products lie.

The OXO example illustrates that consumers often fail to recognize critical design shortcomings associated with current products and services. But even if they can articulate inconveniences or unmet needs, and clearly state their wants and needs for desired product improvements, the information may be misleading because consumers don’t understand the design trade-offs inherent in new product development. As a result, companies that redesign their products in response to what consumers claim they want actually run the risk of undermining their overall value proposition.

An example of a company that got snake-bitten by responding to misguided customer feedback (abetted by misguided survey research) is Walmart.

Some historical context helps set the stage for Walmart’s epic mistake. Walmart founder Sam Walton recognized from the beginning that low prices and wide selection would attract customers. To deliver this value proposition, Walton designed big-box stores jammed with low-priced merchandise, embodying his operating philosophy of “stack ’em high, watch ’em fly.” Merchandising aesthetics took a backseat to everyday low prices in Walmart’s dingy, dimly-lit warehouse stores, anchored by the so-called Action Alley—the primary traffic artery from the front to the back of the store, featuring eight-foot shelves stacked high with deeply discounted items.17

Walmart’s store-design formula proved highly successful in attracting a legion of loyal customers who helped Walmart become not just the largest retailer in the United States, but also the largest company of any kind at the turn of the new millennium. However, as the United States began to emerge from the 2001 recession, sales data showed that Walmart was losing market share to Target, particularly among higher-income shoppers who found Target’s stores more inviting and less cluttered. Walmart examined surveys of its own customers and found a common complaint that the cluttered store layouts were difficult to navigate. So Walmart commissioned a special survey where shoppers were specifically asked, “Would you find shopping here more pleasant if we reduced the clutter?” A vast majority responded yes.

To Walmart, this proved to be compelling evidence of the need to act. After all, it was losing customers to a competitor with a cleaner store layout, and its own customers were urging the company to clean up their cluttered stores. Thus Project Impact began, which remodeled Walmart’s superstores at a frenetic pace, starting in late 2008. Shelf heights were reduced, aisles were widened, lighting was increased, and video monitors were installed to ease in-store navigation. Walmart had clearly listened and responded to the voice of the customer.

The visual impact was impressive, but the business results were not. Within months of the launch of Project Impact, Walmart’s sales began to decline, suffering negative same-store sales growth for eight consecutive quarters, while Target posted positive numbers over the same period. The difference in same-store sales growth between these two companies averaged three percentage points over this period. Now this may not seem like a huge number, but for a company with $400 billion in sales, a 3 percent swing in sales growth represents about $1 billion per month in lost revenue!18

Walmart’s grand plan had clearly backfired. Walmart quietly killed Project Impact in 2011, fired the executive in charge, and began restoring the redesigned stores to their original formats at a cost estimated to exceed $1 billion.19 The question is, what went wrong with Project Impact? Didn’t Walmart give its customers exactly what they asked for?

While it is true that Walmart was losing market share in the five years prior to the launch of Project Impact, Target’s success against Walmart reflected the fact that it catered to a very different kind of customer—younger, with average incomes about 25 percent higher.20 Higher-income customers who defected from Walmart to Target weren’t doing so just because Target stores were less cluttered. Target’s entire merchandising mix was different, as was their brand image.

As for Walmart, its core customer base still valued the time-tested formula of wide selection at everyday low prices. Walmart asked its customers if they would like a less cluttered shopping environment, but omitted the caveat, even if it meant lower availability of some of your favorite products.

Think about it. If you start with a Walmart store of a certain size, remove some aisles, and make the remaining shelves shorter, something has to give. The average Project Impact store wound up eliminating about 15 percent of its branded merchandise. How does such a reduction in available merchandise affect customers? Suppose you prefer Jif peanut butter, but Walmart chose to stock only Skippy and a store brand. Or your baby just had to use Huggies diapers, but now the only choice was Pampers. By the time customers filled their shopping cart at a Project Impact store, virtually all shoppers experienced the loss of some preferred brands. And for customers with strong product brand affinity, this was an unwelcome disappointment. So some shoppers began finding their favorite brands elsewhere, at places like Kroger or Target.

When asked directly—and, as it turned out, improperly—consumers in this case proved to be an unreliable source of what they really wanted. Had Walmart taken the time to develop a more holistic understanding of the preferences and needs of its customers, the company could have avoided a billion-dollar mistake.

How and When Market Research Should Be Used in Developing Innovative Products

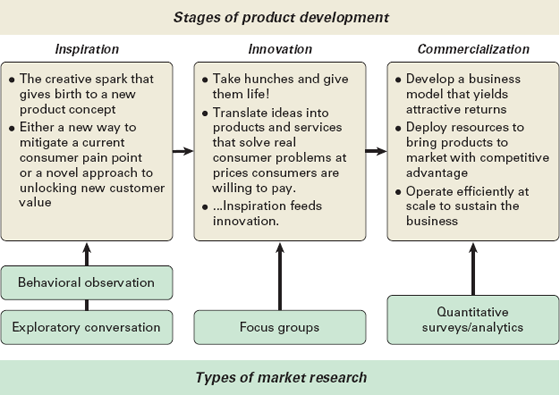

Consumer input is pivotal in identifying new business opportunities, provided that the right type of research is conducted at the right time during the product-development process. Every successful new product moves through three phases of development:

• Inspiration gives birth to a new product concept.

• Innovation translates preliminary ideas into products and services designed to solve real consumer problems at prices consumers are willing to pay.

• Commercialization develops a business model that yields attractive returns, deploys resources to bring products to market with competitive advantage, and operates efficiently to drive profitable growth.

As shown in figure 10.2, the type of market research best suited to guide the creation of innovative new products varies by product-development stage.21

Figure 10.2 Using market research in new product development

Behavioral Observation

Also called anthropological22 or ethnographic research,23 behavioral observation is perhaps the easiest form of market research to conduct, and yet it often sparks the initial insights that allow an innovator to envision a breakthrough product. As baseball Hall of Famer Yogi Berra once noted, “You can observe a lot by just watching.”24

Unlike traditional market research, where respondents are recruited and asked specific, targeted questions about their choices, preferences, and needs, anthropological research is based solely on silently—and often covertly—observing how consumers accomplish various tasks in their homes, offices, or on the go. Thus, behavioral observation research watches what people actually do in performing common tasks.25 The objective of this approach is to understand and empathize with a customer’s user experience with current products and services. Behavioral observations can enlighten researchers about the context in which customers would actually use a new product and about the meaning that a product might have in their lives.

In fact, we’ve already seen numerous examples of this method in practice. The inventors of GoPro, Post-it Notes, and Spanx conceived their ideas based on personal experience. In essence, these innovators were the initial subjects of behavioral observation research. We also saw how OXO confirmed the value proposition for a new type of measuring cup by observing the behavior of a random sample of respondents who volunteered to demonstrate common kitchen tasks.

The singular advantage of behavioral observation methods is in identifying consumer pain points that may be hidden in plain sight from consumers who have simply accepted current product shortcomings as unavoidable inconveniences. In such cases, traditional market-research methods based on direct respondent questioning are unlikely to be fruitful.

Behavioral observation research techniques are derived from the field of anthropology, which has a track record of inferring behavioral insights about subjects that can’t articulate their problems or needs—i.e., animals. Like anthropologists, behavioral observation researchers go to natural habitats where consumers are likely to be involved with a product category of interest.

Suppose, for example, that you were responsible for designing a new SUV model, with the objective of incorporating innovative features to enhance customer convenience. A logical starting point would be to determine whether current vehicles have any design shortcomings associated with everyday use. Since SUVs are typically owned by families with children, a shopping mall provides an ideal vantage point from which to observe how owners interact with their vehicles.

Researchers staked out in such a “natural habitat” would undoubtedly observe the challenge faced by a shopper approaching her SUV in the parking lot with a toddler cradled in one arm, two shopping bags in the other, and car keys buried in her purse. Add in some rain and a stream of cars rushing by, and the problem with putting either the child or the bags on the ground while fishing for the car keys becomes even more apparent.

For years, most vehicle owners accepted this liftgate-opening juggling act as an unavoidable inconvenience of modern-day life. The innovator’s job is to identify such pain points and to envision effective solutions. In this case, some carmakers responded by adding a remote-control button on the key fob to electronically open the liftgate, but this solution still required vehicle owners to have their car keys in hand. In 2013, Ford introduced an even more novel solution on their Escape SUV, allowing owners to open the liftgate without taking out their keys, simply by gently tapping the underside of the rear bumper with their foot. A remote-control unit in the Escape recognizes the presence of the vehicle owner from radio signals sent from the key fob.26

Exploratory Conversation

While behavioral observation is an effective starting point in understanding consumer pain points, it shows only how and what people do, but not necessarily why. As such, supplemental conversations with consumers are necessary to probe for underlying mindsets, motivations, and possible sources of confusion or frustration. Unlike other forms of market research, both behavioral observations and exploratory conversations occur in the immediacy of the actual consumer behavior or product use being studied.

Consider, for example, how product developers might go about developing an improved ticketing kiosk for a commuter-rail station platform. Some ideas for improvement might surface simply by observing how consumers interact with current kiosks, while others require further conversational probing (table 10.2).

TABLE 10.2

Rail Ticket Kiosk Design Ideas

| Observed Behavior |

Likely Improvement |

| Users struggle with where to put their coffee, newspaper, or purse while using the kiosk. |

Add storage shelf on kiosk unit. |

| Users have difficulty using kiosk in bright sunlight or at night. |

Add glare shields or better lighting. |

| Some users seem to repeatedly push touch-screen buttons to initiate an action. |

Tactile force on touch screen needs to be adjusted. |

| Some users hesitate or simply abandon their session. |

Indeterminate without further probing. |

| Wide range in observed time required to complete transaction. |

Indeterminate without further probing. |

While researchers can certainly verify their hypotheses regarding the first three observations by talking to users exhibiting the observed behaviors, there is likely to be little doubt about the inferred design shortcomings or logical fixes. The last two observations, however, would require more contextual understanding to discern the reasons consumers acted in this way.

This is where exploratory conversations come into play. For example, in following up with a kiosk user, a researcher might ask a series of probing questions to determine the root cause of observed user problems, as illustrated by the hypothetical conversation in table 10.3.

TABLE 10.3

Exploratory Conversations on Kiosk User Experience

| Researcher Question |

User Response |

| What type of ticket were you trying to purchase? |

A student-discount, ten-ride, off-peak ticket. |

| You seemed to hesitate while trying to complete your purchase; was there something you found confusing? |

Yes, I couldn’t figure out how to enter my student-discount status. |

| Could you show me the steps you took and explain where you got stuck? |

Sure, the train isn’t scheduled to come for another ten minutes. |

| What did you find confusing about this particular screen? What would have made the choices clearer? |

I don’t know how to go back to the prior screen to change something. |

Notice that these questions are designed to understand how consumers interact with the ticket kiosk on their own terms and in the actual rail station environment. The consumer dialogue directly identifies sources of user confusion that may not have been apparent to the original product designers. This type of exploratory conversation would help to identify refinements to the kiosk user interface that eliminate common sources of confusion or frustration.

Exploratory conversations of this type differ from the more common product-usability tests, in which respondents are typically given a set of tasks to perform in a laboratory setting and then measured on the speed and accuracy of task completion. The problem with simulated, task-based usability tests (also referred to as user interface, user experience, or UX tests) is that the tasks are prewritten and may not reflect how individual users actually interact with a product. Moreover, laboratory environments are unlikely to accurately account for the messy, but very real, environmental distractions of everyday life, such as bright sunlight, loud background noise, the anticipation of an imminent train arrival, etc.27

More importantly, by allowing consumers to frame their actual user experiences in their own terms rather than in response to prewritten scripts, exploratory conversations have the advantage of uncovering unexpected consumer insights that may inspire the idea for a completely different type of product innovation.

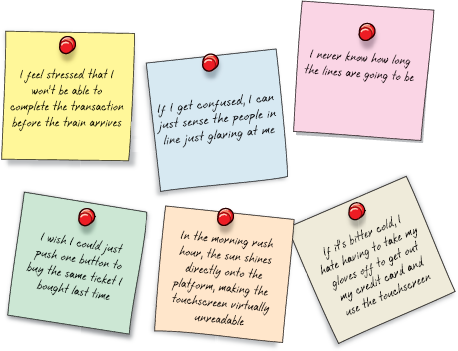

Consider how this might play out in the ticket-kiosk redesign example. After spending a week in the field, interviewing and transcribing the responses from several dozen commuters, suppose the ticket-kiosk design team met to interpret customer feedback. In preparation for a brainstorming session, the team displayed the relevant field-research results on Post-it Notes arranged around the wall of their project office, as shown in figure 10.3.

Figure 10.3 Representative user feedback on ticket kiosk use

One can imagine the ensuing brainstorming discussion between team members:

Person1: We heard a ton of specific suggestions for cleaning up the user interface on some of the kiosk screens, but I’m a bit intrigued by these other user comments that speak to more general concerns.

Person2: Yeah, it sure seems like a lot of users really don’t like our kiosks very much!

Person3: That’s right, but their complaints are all over the map.

Person1: Maybe not. There must be some common themes here.

Person2: Well a few of these comments seem to indicate that some users find using ticket kiosks stressful.

Person3: That’s right. And even if we improved the user interface, that still wouldn’t eliminate the stress of completing a transaction before the train came.

Person1: In fact, a cleaner user interface wouldn’t really address any of these concerns.

Person2: Maybe that’s the common link we’re looking for…. Maybe a kiosk on a commuter-rail platform is actually a terrible place to buy a train ticket!

Person3: If passengers could buy tickets online and print them at home, all of these concerns would go right away.

Person1: That’s right. And a system designed for PCs and mobile apps would be easier to use.

Person2: Yeah, but why print the tickets? We could just display tickets digitally on a smartphone…. Just like the airlines do.

Person3: But not everyone has a smartphone.

Person1: So maybe those passengers could buy their tickets on the train, which is possible today. I’m sure we could design a scanner device which would both verify digital tickets and process tickets sales on board.

Person2: That’s a good idea. And we could pay for the new devices with all the money we save by eliminating ticket kiosks.

Person3: Hey, I thought we were supposed to be redesigning the station-platform kiosk.

Person1: Maybe that’s a really bad idea after all!

As I have shown in these examples, behavioral observations and exploratory conversations are well suited to help identify opportunities for innovative new products, which solve real consumer problems. An in-depth exploration of the art and science of well-designed behavioral research goes beyond the scope of this book, but readers interested in pursuing this subject further would be well served by two excellent books devoted to this subject: Well-Designed: How to Use Empathy to Create Products People Love by Jon Kolko,28 and Customers Included: How to Transform Products, Companies, and the World—With a Single Step by Mark Hurst.29

Focus Groups

Up to this point, I have raised several questions about the value of focus groups, but this technique can definitely play a useful role, if used at the right time and for the right purpose. As many readers may have personally experienced, focus groups involve using a trained moderator to engage a panel of recruited respondents in a group dialogue, while the proceedings are often observed by interested spectators seated behind a one-way mirror. Focus groups have been used for a wide variety of research purposes, such as testing audience reactions to different movie endings or political ads, comparing the taste of different cookie-dough recipes, finding out what customers like and dislike about shopping at different stores, and seeking suggestions for desirable new product features.

What focus groups are good at is capturing consumer opinions, particularly when respondents are allowed to see, taste, or try alternative product concepts. In these situations, respondents can provide instant feedback, based on actual observation or trial product use. For example, focus groups have been particularly useful in guiding food companies toward reformulating their recipes. In one celebrated case, Domino’s used actual video clips of focus groups criticizing the company’s pizzas as the centerpiece of a television advertising campaign, promising viewers that the company was listening and committed to making improvements. In the company’s television ads and on its Facebook page, focus-group respondents were shown making disparaging remarks after tasting Domino’s pizzas, including the following:30

“Your pizza tastes like wet garbage.”

“Domino’s pizza crust to me is like cardboard.”

“Worst excuse for pizza I ever had.”

This painful feedback proved to be a win-win application of focus-group research for Domino’s and the consumers alike, as it triggered recognition of the urgent need for management action, guiding the development of a tastier pizza, and generating consumer goodwill in response to the company’s disarmingly candid public mea culpa. Comparing market performance in the five years before and after Domino’s launched its focus-group advertising campaign in 2010, the company’s market cap went from losing more than half of its value to increasing more than tenfold. This is quite an endorsement for the value of deploying and responding to focus-group research.

On the other hand, focus groups are generally not good at eliciting reliable insights on perceived needs or abstract speculation on desired new product features. In this regard, we’ve already seen several examples earlier in this chapter that affirm Steve Jobs’s assertion that “people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”31

An additional limitation of focus-group research is the inevitable interpersonal dynamic associated with a group setting. Talkative, dominant, or belligerent respondents may drown out or inhibit dissenting views. And at the very mention of unseen observers behind the fake mirror, some respondents filter their opinions, perhaps unwittingly, according to what they think the hidden audience wants to hear.32

So where does that leave us with respect to the value of focus-group research in the development of new products? Focus groups can be a useful approach provided they are used to elicit feedback after a product-development team has created working prototypes for innovative new products. Focus groups can provide far more valuable feedback in reacting to specific, tangible product concepts than in opining in the abstract on what they might hypothetically like.

Quantitative Surveys and Analytics

As we have seen, qualitative market research is most useful in the early stages of new product development. But as a promising new product moves closer to full-scale commercial launch or an existing product is reconfigured, there are hard decisions to make that entail significant investment risk. At this point, quantitative research and analytics are most appropriate in helping project teams lock down the final configuration of the product, deploy production and distribution assets in line with the expected size and composition of the market, monitor sales, and detect shifts in the market and competitive environment.

For example, consider the questions facing the developers of Marriott’s Courtyard hotel chain, the E-ZPass automated toll-payment system, and JetBlue’s airline service, as executives neared the launch of their respective products:

• How much value in terms of willingness to pay do consumers associate with hotel amenities such as room size and decor, type of restaurant and food service, leisure facilities, and guest services?33

• What is the relative value for consumers of elements of the E-ZPass system, including number of lanes available, ease of tag acquisition, cost savings, invoicing process, and other uses of the tag?34

• When considering JetBlue’s service offerings and fare levels, how do consumers trade off the value associated with in-flight amenities (e.g., legroom, entertainment systems) with travel perks such as free bag check?35

These are all examples of the design trade-offs required in putting the final touches on a new product or service that can ultimately determine demand, consumer WTP, and profitability.

To optimize their product configuration, all of these companies used conjoint analysis, a quantitative technique for determining the value consumers place on individual product attributes, and how buyers make trade-offs in choosing between competing products. In a conjoint analysis, prospective consumers are presented with descriptions of competing products with distinctly different attributes and asked to rate their likelihood of choosing each alternative. By analyzing the patterns of preferences, conjoint analysis can be used to determine how companies can achieve the most meaningful product differentiation, where they can add the most consumer value at the least company cost, how price affects consumer choices, and what market share can be expected for a range of alternative product configurations.36

There are limitations associated with conjoint analysis and other stated-preference models, all of which depend on how accurately consumers rate their preferences among hypothetical product bundles. Consumer intentions and their actual behavior are often markedly different. Nonetheless, quantitative consumer-choice models are valuable tools, once product developers have narrowed their focus to optimize the final launch configuration of a product.

Another important use of quantitative methods in late-stage product development is in refining estimates of the size of the addressable market and the expected level of actual sales. Product-development teams should have undertaken a preliminary assessment of market potential early in the development process. But as the launch date approaches, hard decisions need to be made on manufacturing capacity, sales-channel assets, and marketing budgets.37 By drawing on early-stage learnings about target market characteristics and how competing products are perceived, analytical rigor should be applied in forecasting expected demand levels prior to full-scale launch.38

Finally, even if the launch of a new product has been successful in meeting or exceeding initial business forecasts, it is critical to assess ongoing changes in sales or use. Quantitatively monitoring demand trends can serve as an early indicator of what is happening in the market, if not why, and point to the need for further targeted research to understand evolving changes in consumer preferences and the competitive landscape.

Estimates of failure rates for new product launches range from 70 percent to over 90 percent, so there is obviously considerable room for improvement in the business processes used to conceive, refine, and launch truly great products.39

Putting the Pieces Together—How Honda Developed the Element

Tracing the development of a complex product like Honda’s Element SUV effectively illustrates how and when different types of market research should be used to create innovative new products.

The Honda Motor Company has been a paragon of product-development excellence for more than seventy-five years. Born from the devastation of post–World War II Japan, Honda established an early reputation for engineering prowess by launching a reliable and efficient range of small motorbikes and scooters in the late 1940s. By 1960, Honda had extended its product range to larger and more sophisticated models, emerging as the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world. In the decades that followed, Honda exploited its world-class engine technology by successfully expanding into entirely new product categories, including power products (e.g., tillers, generators, lawn mowers), automobiles and trucks, and eventually, jet aircraft. In each case, Honda started with well-designed, low-priced models before moving progressively upscale to gain additional market share.

As a case in point, Honda entered into the U.S. car market in 1969 and soon achieved success with the Civic, a technologically advanced small car that provided greater fuel economy than competing models from American carmakers. Its next product was the midsize Accord, which won awards as the best sedan from Road & Track and Car and Driver magazines shortly after its 1976 market entry. Within five years, the Accord became the best-selling car in the U.S. market.

Honda moved further upscale in 1986, becoming the first Japanese car manufacturer to launch a luxury brand in the United States. Its Acura brand featured a line of high-performance, stylish sports cars and sedans carrying premium price tags. From there, Honda expanded its market reach by adding the Odyssey minivan, recognized by Consumer Reports as the best minivan in the U.S. market shortly after its 1995 launch. Finally, Honda attacked the SUV category, by once again starting at the low end with the compact CR-V model, before moving progressively upscale with the larger Pilot and Acura MDX models.

By 2002, Honda was selling over 1.2 million motor vehicles in the United States, competing profitably in virtually every segment of the market. Despite such stellar performance, Honda recognized two related brand weaknesses that threatened to limit its future growth.

Honda’s brand image was viewed as pragmatic, rather than exciting or aspirational.

From its inception in the U.S. market, Honda’s engineers had done a masterful job developing cars that were fuel efficient, reliable, safe, and comfortable. Not surprisingly, these attributes served to associate Honda’s brand image with practical, family-oriented, and conservative vehicles. There’s nothing wrong with such positioning, as Honda’s sales growth attests. While its emphasis on practicality appealed to young families and female buyers, Honda’s brand image proved to be off-putting to other segments of the market.

Honda generally did not appeal to young, male first-time car buyers.

In particular, Honda’s market penetration among young male drivers was considerably below competitive norms. As one company sales director recalled, “We had products for young women and families, but nothing focused on young men.”40 This was an issue of considerable concern to the company because the young-buyer segment was emerging as a sizeable market opportunity for car companies. When Honda surveyed U.S. demographics as the new millennium approached, it recognized that over half of first-time new-car buyers were less than thirty years old. This age group was likely to grow as the children of baby boomers reached driving age. The company concluded that it simply could not continue to ignore millennial male customers.41

Thus began the business imperative for Honda’s first vehicle designed specifically to appeal to young men. Honda formed the Element concept-development team in 1998 at its R&D facility in Torrance, California. In keeping with the project mission, most of the design team were relatively young men themselves, charged with the responsibility of creating a compelling design that would resonate with the core values and beliefs of male millennials.

The starting point was to understand the motivations and needs of this new, unfamiliar customer group. Honda certainly had access to numerous market-research studies that profiled the characteristics of millennial customers.42 While such insights served as an interesting backdrop to the project team’s mission, in reality, such broad generalizations—e.g., millennials are idealistic, optimistic, and flexible—provided little guidance on specific design priorities (table 10.4).

TABLE 10.4

Characteristics of Millenials

| Demographics |

Attitudes and Beliefs |

| – Born 1980–2000 (80 million)

a. Also known as echo boomers, millennials.

b. Children of baby boomers (72 million).

– Notable demographics:

a. 25 percent live in single-parent households.

b. 75 percent have working mothers.

c. Ethnically diverse—34 percent are black, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American.

– Shaping events: O. J. Simpson trial, Monica Lewinsky, Middle East Conflict, Sadaam Hussein, Oklahoma City bombing, Columbine shootings, Reality TV, and 9/11.

– Millenials in popular culture: Hilary Duff, Bow Wow, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, Prince William. |

– Young and trend-conscious

– Idealistic, optimistic, and flexible.

– Hard workers; highly entrepreneurial.

– Socially responsible; particularly concerned about the environment.

– Very comfortable with technology; like to multi-task.

– Have a hunger for feedback and rewards.

– Spiritually traditional: 89 percent of millennials state that they believe in God. |

The team also obtained detailed data on which vehicles were currently most popular with male millennial drivers, but this information was also of limited use. After all, Honda did not want to merely copy existing design themes; the company was determined to identify the unmet needs of its target customer group to guide the design of a unique product with the potential to achieve breakthrough market success that would burnish Honda’s image.

Honda realized that simply asking a sample of young males directly what they might be looking for in a new vehicle was likely to be of limited value, and perhaps even misleading. Therefore, Honda appropriately started their project with observational research to better understand how millenial men currently used their vehicles.

The project team decided that the best place to start the “natural habitats” where millenial men were likely to congregate. So, armed with video cameras and tape recorders, the researchers headed to the X Games—an annual ESPN-sponsored extravaganza of extreme sporting events, primarily appealing to young men—and to the beaches and boardwalks of southern California to closely observe how young men interacted with their vehicles.

What emerged from these detailed observations and subsequent exploratory conversations was the persona of a social, active millennial male that Honda dubbed “Endless Summer.”43 The lifestyle of prospective Endless Summer customers placed multiple demands on how their vehicles were used, which began to frame high-level design themes for the still inchoate Element SUV (table 10.5).

TABLE 10.5

Preliminary Design Themes for Endless Summer Personas

| Personal Characteristics |

Vehicle Design Implications |

| Single |

No need to compromise to appeal to spouse’s taste. Go all-in on designing a “guy’s car.” |

| Social (lots of friends) |

Needs to seat four to five…. No pickup truck for this persona. |

| Highly active |

Capable of carrying lots of “boy toys”—mountain bikes, surfboards, skis, etc. |

| Well traveled and nomadic |

Spacious enough to serve as a part-time camper and to haul home furnishings for frequent moves. |

| Educated, hip, and environmentally aware |

Exudes edgy styling and features that the target could clearly identify with. No gimmicks. |

With ongoing observational research, Honda’s engineers and stylists then began translating their deepening understanding of target customer needs into specific vehicle features that would directly support the diverse lifestyles of Endless Summer males. For example, the project team observed the need to accommodate conflicting vehicle missions, such as hauling mountain bikes or surfboards in the morning and carrying five friends to a party in the evening. To meet these requirements, Honda designed side-folding rear seats that could quickly be flipped up or down.

The team also responded to the target customer need to haul messy recreational equipment, like sandy surfboards or muddy mountain bikes, by adding several unusual design features: pillar-less, wide-opening side doors, a large clamshell tailgate, and a fully waterproof, hose-down interior. No other vehicle on the market incorporated such design features.

After observing how Endless Summer males often ate, lived, and played in their vehicles, the project team included a center-console storage container designed to carry supersized shakes and fries, and a sound system that amplified bass tones eight times louder than on the staid Honda Civic.

Finally, during exploratory conversations, the project team detected a strong affinity among Endless Summer respondents for products that authentically reflected their lifestyle preferences, and a dislike of gimmicky products that claimed to be hip, but were not. In response, the engineers strove to execute a thoughtful integration of all key design elements: edgy styling, spirited handling, and relevant functionality.

As the engineering effort progressed, the project team recruited focus groups of social outdoor enthusiasts on college campuses across the country to react to sketches of evolving design concepts. After several iterations to refine the design of the Honda Element, the end result emerged as a distinctively boxy SUV, with numerous features that uniquely addressed the needs of the Endless Summer segment of millennial men.44

As Honda prepared to launch the Element in model year 2003, the marketing department refined its sales forecasts, based on a quantitative analysis of demand for competing vehicles on the market. Recognizing that the Element was targeting a very specific customer segment with a new, radically styled vehicle concept, Honda’s initial U.S. sales forecasts called for relatively modest sales of fifty thousand units per year.

Figure 10.4 Honda Element

So how did the Element fare, and did Honda achieve its business objective of increasing its market penetration and image strength among millennial male car buyers?

The initial market reaction was positive. In its first year, the Element was named Best Small SUV of the Year by the influential Automobile magazine,45 and U.S. sales of 67,478 comfortably exceeded Honda’s initial target. But a closer examination of the sales data revealed that only 20 percent of first-year buyers were young men, accounting for less than 2 percent of all new cars sold that year to millennial males. The remaining Element sales went to older customers, most of whom were over forty. Moreover, sales of the Honda Element peaked in its first year, declining steadily thereafter, and falling below twelve thousand units by 2011, when the model was discontinued.

So what went wrong? Before answering that question, let’s first recap what went right. Honda actually did an admirable job of understanding the unmet needs of their target customers and designed the Element to uniquely fulfill real customer requirements. As described, Honda properly sequenced their use of observational research, exploratory conversations, focus groups, and quantitative research to develop and launch a thoughtfully designed vehicle that uniquely met the needs of target customers.

But, as it turned out, Honda missed a few critical red flags.

First, not all millennials are Endless Summer archetypes. When I share a description of Honda’s Endless Summer target customers with my MBA students (who themselves are in that target age group), few identify with the Endless Summer persona. The characteristics and lifestyles of students sitting in an MBA classroom in New York City don’t align very well with the persona of young men who frequent the X Games in Aspen or the beaches and boardwalks of southern California. The same could probably be said for the majority of millennial men living in Chicago, Atlanta, or Phoenix. The Honda Element project team themselves lived and worked in southern California, and so focused their market research efforts on hard-core outdoor enthusiasts without first pausing to reflect on how small a customer segment that might actually be.

Moreover, Endless Summer customers who worked to live, rather than lived to work, may not have had the disposable income to afford the relatively pricey Honda Element. For example, the Element launched in the U.S. market in 2003 at a base price of $16,100, more than 25 percent higher than Honda’s other entry-level vehicle, the Honda Civic, which was priced at $12,800. As such, it is not surprising that Honda Element sales were higher among older, more affluent customers.

If Honda were truly committed to improving its market penetration of millennial customers, it would have developed a broader array of suitable products rather than just focusing on the Element, which aimed at too small a target. In contrast, in seeking to attract more young male customers, Toyota created a whole new brand (Scion) with multiple models to appeal to a broader set of millennial buyers, including the xB model, a small, boxy SUV, comparable to the Element. In retrospect, the Element appealed to only a small subset of male millennials, and the model wound up as an orphan within Honda’s broader lineup of practical cars and light trucks.

While there is much to learn from Honda’s best practices in applying user-centered design and appropriately sequencing the correct types of market research, the failure of the Element demonstrates the imperative to target new products at a sufficiently large segment of the market. The Element hit the bullseye, but Honda’s target was too small.