Among the unique characteristics of immigration policy in the modern nation-state is the way that it is intimately linked to visions of national identity. Decisions made regarding who can and cannot enter a country, under what formal legal status individuals and families are allowed to enter a country, and whether paths to gain full citizenship for immigrants exist all directly impact what peoples make up a nation, what languages are spoken and what religions are practiced there, and, if immigrants are allowed to become voting citizens, whose interests are positioned to make legitimate claims on the state. A country’s immigration policy directly affects important elements of a nation’s sense of its own people, culture, values, and politics, all of which are fundamental elements of national identity.

It should not be surprising, therefore, that immigration policy has consistently been a major source of controversy over the course of American political development. The stakes in the contours of national identity are high. In 1751, prior to the writing of the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin in an essay about population growth and the economy in the colonies passionately expressed his concern that German immigrants were a threat to English-derived Anglo culture. He stated,

And since Detachments of English from Britain sent to America, will have their Places at Home so soon supply’d and increase so largely there; why should the Palatine Boors be suffered to swarm into our Settlements, and by herding together establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion.1

Franklin’s concerns are clear: fear of demographic change, the rise of ethnic enclaves, the maintenance of home country language, and the possibility that Anglo cultural domination could not be maintained. Concerns with maintaining Anglo-driven notions of national identity existed even prior to the actual existence of an American nation-state.

Mae Ngai and Aristide Zolberg, in their distinct and excellent analyses of the path of U.S. immigration policy, demonstrate how allegations regarding the willingness and ability of immigrants to integrate into the American nation-state were often at the heart of major national debates regarding national identity in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries.2 Great concern was expressed when substantial numbers of immigrants from Ireland arrived in the United States beginning in the 1840s. Not only were there continuous examples of native versus immigrant conflict in large cities such as Boston, New York, and Chicago, where many Irish settled;3 it was during this time that the Know-Nothing Party was established on a platform of severely restricting further immigration. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Emergency Immigrant Quota Act of 1921 were driven by fears of the impact immigrants from this Asian country would have on the culture and society of the entire nation, and especially in areas of the country where large concentrations of these immigrants settled.4

The municipal reform movement of the Progressive Era was explicit in its criticism of the perceived gains made by ethnic immigrant communities in major cities. Starting in the late 1880s and through the first half of the 1950s reformers alleged that the political empowerment of immigrant-derived ethnic communities through urban political machines harmed the long-term interests of sectors of urban communities and the entire nation. These concerns were couched in cultural, class, and political terms and ultimately led in many communities to the establishment of entirely new forms of professionalized government administration, civil service systems, at-large and nonpartisan elections that were all designed to limit the political influence of immigrant leaders and their respective communities.5

Interestingly, there are at least two explicit examples of immigrants from Mexico being targeted through severely restrictive immigration policies culminating in forced repatriations and deportations. Arguments regarding the threat posed by Mexican immigrants to elements of national identity and especially to employment competition with “American” workers were apparent in each of these cases. Despite the fact that Mexican immigrant laborers were exempted from the limitations of the Immigration Act of 1924 (which further established quotas), through administrative actions authorized by President Herbert Hoover, it is estimated that approximately 1 million Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans were forcibly sent to Mexico between 1929 and 1937, during the Great Depression. It is also estimated that 60% of those deported were U.S. citizens.6

In 1954 President Dwight D. Eisenhower expressed great concern over the number of unauthorized workers across the Southwest. Agricultural and other employers had come to depend on these workers to harvest crops and do other work in many parts of these states. In July of that year, President Eisenhower authorized the director of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to pursue Operation Wetback with support from municipal, county, and state officials. It is estimated that up to 1.3 million Mexicans were deported or voluntarily returned to Mexico within one year. Individuals were sent by both train and ship into central and far southern Mexico to limit the likelihood that they would try to reenter the United States.7

In each of these cases the perception of threat to national identity the immigrants posed was real. Important segments of the public, and especially influential political leaders, accepted the validity of the alleged threat and took action to limit immigration on the basis of this determination. However, what was much less clear was the extent to which the understanding driving this sense of threat was based on facts and the extent to which it was based on expectations largely driven by racism, prejudice, anecdote, and misinformation.

It is the purpose of our essay to examine the extent to which current concerns of threats to national identity posed by immigrants from Latin America are based on informed understandings and the extent to which they are driven by other factors. We begin by assessing the accuracy of targeting immigrants from Latin America as the major source of threats to American national identity. Although concerns are expressed regarding potential terrorists and other unauthorized immigrants, it is the concern with the high percentage of immigrants from Mexico and countries in Central America that drives much of the current controversy and debate regarding comprehensive immigration reform. Second, we assess the stated concerns regarding the patterns of assimilation and acculturation of immigrants from Latin America. We specifically examine choices and experiences regarding language use, religion, social capital, military service, education, income, intergroup marriage, and political values. In the final section, we conclude with a consideration of the risks the nation takes if it again pursues a set of policies that are largely driven by uninformed perceptions of threat and perceptions of anticipated short-term political gain. These are risks that we think can be minimized only through an honest and transparent assessment of what role Latinos and Latino immigrants are likely to play in the future social, economic, and political development of the United States.

The Latino experience in America has always been inextricably linked to national debates over immigration. For starters, though some small share of the Latino population traces its roots in the United States to the transfer of sovereignty over the southwest in the wake of the Mexican-American War, for most Latinos the immigration experience is far more proximate.8 The Census Bureau reports that around 65% of Latinos in the United States are foreign-born or were born on the island of Puerto Rico, and about 40% of the rest are born to immigrant parents, that is, parents who are first-generation residents of the United States. Taken together, this means that 87% of all Latinos in the United States have at least one foreign-born grandparent. The immigration experience, then, is proximate in the collective memory of most families. Indeed, American politicians eager to crack down on immigration don’t realize that the social distance between immigrants and the U.S. Latino population is so small that it is nonexistent. When the vast majority of Latinos in the United States attend a family wedding or baptism or sit down to holiday dinners, it is nearly certain that the immediate family is sure to include one or more immigrants.

A second important point of connection between the immigration debate and the larger Latino community is the temporal structure of this immigration. Because Latin American migration originates from nations closer to the United States than was the case in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, circular migration, frequent visitation, and familial networking reinforce cultural and family ties to nations of origin. The Ellis Island experience of European immigration was truncated firmly with the dramatic reduction of immigration after the passage of the National Origins Act, part of the Immigration Act of 1924. By contrast, today’s Latin American immigration remains ongoing, in spite of continuous attempts to curb it, and it therefore reinforces existing connections and cultural modalities by refreshing the assimilating population with new arrivals still firmly rooted in the language and culture of the society of origin.

Third, as the late Harvard professor Sam Huntington correctly noted in Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity,9 Latin American migration differs from past experiences because of its homogeneity. While European migration brought to the shores a variety of languages, ethnicities, and national origins, the current wave of migration includes among the largest percentage of immigrants from one country (Mexico, 30%) and speaking one language (Spanish, 45.5%) than at any other point in our nation’s history. One has to go back to the colonial era to find such a heavy representation of a single national or linguistic identity among the American immigrant population. This concentration is likely the greatest source of unease among some segments of the American populace.

Fourth, current immigration from Latin America—perhaps more than that of any other group—is having widespread effects across the nation and is no longer a regional issue. Table 5.1 reports the growth and size of the Latino population in the ten states with the fastest rates of increase. With the exception of Nevada, none is in a region of the country generally associated with Latinos.10 Both the South and the Midwest have witnessed rapid Latino—almost exclusively immigrant Latino—population growth in the last twenty years. Most of these communities have little experience with Latino populations and, for some of the Midwestern communities, racial and ethnic diversity of any sort. Immigration, and particularly Latino immigration, is experienced by a much broader cross section of American society than has previously been the case.

Thus, immigrant politics and related elements of Latino politics are inseparable in the minds of many voters and analysts alike. When the word immigrant is uttered what comes to mind for most Americans is a person of Latin American origin. We don’t want to overstate this, of course. As earlier chapters in this volume have already made clear, Latino immigrants are part of a larger and much more complex process, still involving substantial European migration (particularly from Eastern Europe), smaller but meaningful numbers from Africa and the Caribbean, and, of course, substantial Asian immigration. None of these other groups, however, enjoy having their photos among the graphics for CNN’s Lou Dobbs Tonight or the Minutemen Civil Defense Corps. Such a distinction is reserved for Latinos. As popularly conceived, immigrants are Latinos.

How, exactly, does immigration pose a sociocultural threat? The answer is somewhat complex as it involves both beliefs about the immigrants’ values and social convictions—and the fear that these differ considerably from American values—as well as the willingness of those immigrants to adopt American forms of cultural expression, including language, religion, and other social practices. As previously stated, this fear of difference has deep roots in American history and is continually reflected in debates on language politics, school curricula, religious bigotry (particularly anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism in the American context), and overhyped discussions of public health, crime, and poverty. One need only consider Huntington’s Who Are We? and recent legislative efforts in Arizona to ban racially or ethnically identified student organizations to witness these largely cultural fears in action.

TABLE 5.1. CHANGE IN HISPANIC POPULATION BETWEEN 1990 AND 2000

Source: Figures are calculated from Table 2, Betsy Guzmán, The Hispanic Population: Census Brief 2000 (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, May 2001), 4.

But are the central tenets of these perceptions of threat based in fact? That is, is there any evidence we can bring to bear on the question of assimilation and acculturation by new Latin American immigrants?

For starters, a generation of research on language acquisition and other markers of social assimilation suggests that these fears are unfounded.11 Moreover, our own research and recent data collection suggest that on several dimensions—including the all-important language issue—Latin American immigrants to the United States assimilate exactly as we would expect them to. Data from the Latino National Survey reveals that only first-generation Latino immigrants chose Spanish as their preferred language for interviews given by bilingual interviewers. Among second-generation Latinos, i.e., those who are born in the United States to at least one immigrant parent, just under three-quarters, 73.7%, prefer to answer questions in English, and an overwhelming 90.4% of third-generation and 91.3% of fourth-generation Latinos do the same. The data also reveal that only among the first generation did a minority of respondents, 38.3%, report English proficiency. By the second generation, the percent reporting English proficiency rose to 91.6%; it is 98.6% in the third generation and reaches near unanimity at 99% in the fourth generation.

Table 5.2 reveals that this propensity to learn English coexists with a reported capability to be proficient in Spanish also. However, Spanish proficiency declines among Latinos who are more distant from the immigration experience. Not surprisingly, 99.2% of first-generation Latino immigrants indicate that they are proficient in Spanish. Interestingly, the data demonstrate that in the second through fourth generations there is a considerable amount of reported bilingualism. A full 91.6% of the second generation reports Spanish proficiency, but only 68.7% and 60.5% report proficiency in the third and fourth generations, respectively.

The data in table 5.3 further demonstrate the commitment of Latino immigrants, even in the first generation, to learn English. When asked the question, How important do you think it is that everyone in the United States learn English? over 95% of all respondents, across all generations, report that it is somewhat or very important. Interestingly, the first generation had the highest percentage of respondents, 94.1%, indicate that it is very important to learn English.

This support for learning English, however, coincides with a desire to maintain the ability to speak Spanish. In the first generation, 98.3% of respondents indicated that it is somewhat or very important to maintain Spanish. The percentages are 98.1, 90.9, and 88.9% across the second, third, and fourth generations, respectively.

In sum, these data reveal that Latinos, across generations, do not see the ability to speak English as in competition with an ability to speak Spanish. Language is seen as additive rather than subtractive. Those who report concerns about the assimilability of Latino immigrants on the basis of high rates of Spanish language maintenance make the mistake of not recognizing that both English and Spanish are highly valued by Latinos across generations.

TABLE 5.2. LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY ACROSS GENERATIONS

Source: Original figures calculated by the authors from the Latino National Survey 2006 (LNS), Luis R. Fraga, John A. Garcia, Rodney E. Hero, Michael Jones-Correa, Valerie Martinez-Ebers, Gary M. Segura, Principal Investigators. For a description of the scope and methodology of the study, as well as how to access these data, see http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/ICPSR/STUDY/20862.xml at the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan. Also see toplines and related documents at http://depts.wash-ington.edu/uwiser/LNS.shtml at the University of Washington.

Cell entries are weighted percentages. N=8634

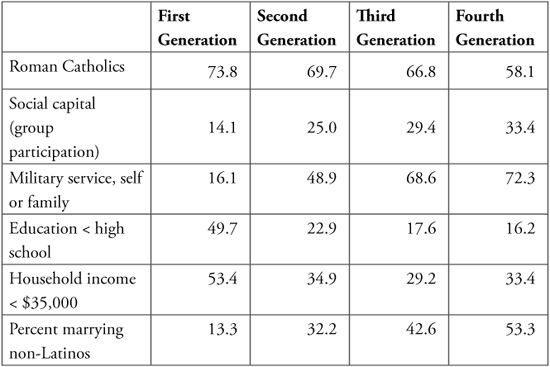

Table 5.4 reports data from the Latino National Survey on several other indicators of acculturation. On virtually every indicator presented, Latino immigrants and their descendants adapt quickly to the United States and its culture. For example, while Roman Catholicism characterizes almost three-quarters of the foreign-born population, the share of Latinos in the fourth generation or later who are Catholic declines to 58.1%, indicating a religious diversification. Participation in civic groups increases from 14% in the foreign-born to approximately a third of fourth generation respondents, and the share of all respondents who have an immediate family connection to the military approaches 50% in the second generation and exceeds 70% by the fourth. High school completion rates climb and poverty rates decline, though not monotonically and not to the degree we might like. Of particular importance to those concerned that Latinos might come to constitute a permanently externalized and racialized subpopulation, a majority of those in the fourth generation (and, indeed, almost a third of those in the second generation) marry outside of their group. In summary, on this varied list of social indicators, there is little evidence of long-term and intergenerational Latino isolation and cultural separation, and plenty of evidence that Latinos become less and less distinct over time.

TABLE 5.3. IMPORTANCE OF LEARNING ENGLISH/RETAINING SPANISH ACROSS GENERATIONS

Source: Original figures calculated by the authors from the Latino National Survey 2006 (LNS). Cell entries are weighted percentages. N=8634

TABLE 5.4. SELECTED MARKERS OF SOCIOCULTURAL ASSIMILATION

Source: Original figures calculated by the authors from the Latino National Survey 2006 (LNS). Cell entries are weighted percentages. N=8634

Of course, these measures capture several behavioral or demographic characteristics without necessarily reflecting specific value judgments. Social and economic assimilation would be of little value if these immigrants and their progeny hold political beliefs antithetical to American political traditions. Were that to be the case, immigrants would represent a fifth-column, or alienated, population that does not share the political culture of the whole and, by extension, that may not share the acceptance of political practice and legitimacy of political institutions and outcomes. The implications for threats to national identity and political stability are obvious.

The logic of this argument is flawed on several dimensions. First, the evidence has long suggested that this fundamental difference in political orientations does not exist.12 Moreover, it presupposes a model of political orientations devoid of socialization effects. Our data echo these earlier findings and clearly illustrate a general commitment to political values often identified as “American” and one that grows across generations.

Table 5.5 reports respondent reactions to questions probing their commitments to equal political rights, individual self-reliance, and equality of opportunity, each of which has deep roots in American political culture. Over three-quarters of all foreign-born respondents profess a commitment to political equality, a percentage that grows over the generations. Similarly, about 65 to 70% of respondents across generations articulate a positive response to a self-reliance probe. More important, however, the level of strong agreement declines while the level of soft agreement increases across generations, suggesting a socialization process to the idea that systemic factors occasionally hold back otherwise motivated and capable individuals.

One troubling point of disagreement is the relative willingness of foreign-born Latinos to accept inequality of social and economic opportunity. Only a third of first-generation respondents disagreed with the statement that the existence of inequality of opportunity was “really not that big of a problem.” Once again, however, the assimilative force of American life and mythos is demonstrated. In a single generation, disagreement with this statement jumps to almost 50% and stays there.13

TABLE 5.5. EXPRESSIONS OF CORE POLITICAL VALUES

Source: Original figures calculated by the authors from the Latino National Survey 2006 (LNS).

Actual Question wording:

Would you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree with the following statements, or do you have no opinion?

A. “No matter what a person’s political beliefs are, they are entitled to the same legal rights and protections as anyone else.”

B. “Most people who don’t get ahead should not blame the system; they have only themselves to blame.”

C. “It is not really that big of a problem if some people have more of a chance in life than others.”

In summary, there is little evidence that Latino immigrants and their descendents are in any way distinct from the long and rich traditions of immigration to the United States. Latino immigrants assimilate in predictable patterns, hold political views generally consistent with other Americans, and their children and grandchildren increasingly resemble the rest of the society. This is not to say that Latino immigrants face a smooth path to cultural, social, and political incorporation. Nor are we suggesting that there are no cultural effects from the traditions and practices brought by immigrants from their countries of origin. Rather, we are arguing that there is nothing exceptional about Latino immigration and the immigrants themselves. And, in the context of the history of immigration and social diversification in the United States, Latino immigration poses little threat to American national identity.

We have suggested that understanding the politics of immigration requires us to examine the broader implications of immigration from Latin America for our society and culture and especially for our sense of national identity. We have identified a number of the major understandings and clear misunderstandings among the American public, advocates, and public officials that contribute to contentious debate. These misunderstandings are sometimes driven by uncertainty but also occasionally by political intentions and interests. We caution the reader that the current immigration regime—and all of the alternatives proposed to change it—serve the interests of someone. Policy that serves the interest of no constituency is far more easily changed than policy that has at least one client group. What are some of the major risks the nation accepts if it continues with the current regime? How likely it is that a new consensus can be built to promote comprehensive immigration reform? Whose interests will be served most under a new immigration regime?

One major risk that the nation takes if it continues with the current immigration regime is to exacerbate the significant political divisions and cleavages between anti-immigrant advocates of restrictionist immigration policies and immigrants and immigrants’ rights advocates. In such a scenario, each camp will only entrench itself further in the virtues of its own views and prevent any consensus that would improve our current policies.14

Immigration politics has been contentious for the last several years. House Resolution 4437, the Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005, sponsored by Rep. James Sensenbrenner (R-Wisconsin), then chair of the House Judiciary Committee, and thirty-five cosponsors, made it a felony to be in the United States without proper documents or to assist, direct, or encourage someone to attempt to enter or remain in the United States if that person did not have proper authorization. The bill was passed in the House by a vote of 239 to 182. This led to one of the largest peaceful civil protests in U.S. history. On March 25, 2006, at least 500,000, and by some estimates as many as 1 million, people marched in protest to HR 4437 in downtown Los Angeles. On May 1, 2006, an estimated 3 to 5 million marched in over sixty cities in forty-four different states.15

Nonetheless, all of the contenders for the Republican nomination for president took positions focusing on enhancing border security that followed the lead of Rep. Tom Tancredo (R-Colorado), one of the most vocal proponents of a severely restrictionist immigration policy. The lone exception to this was Sen. John McCain (R-Arizona), and even he, as was noted in chapter 1, later shifted to a more conventional Republican position.16

Some Republicans, such as former Senator Chuck Hagel (R-Nebraska), argue that if the Republican Party gained the reputation as the anti-immigrant party, it would alienate many Latino voters and severely limit the chances that the party could build on gains with Latino voters made during the 2000 and 2004 presidential campaigns of George W. Bush. In 2006 the GOP lost in the fifth and eighth congressional districts in Arizona because it nominated candidates so far to the right on immigration reform that the Democrats were able to win moderate voters. It is estimated that in the 2006 congressional election Latino voters, on the average, gave only 29% of their votes to Republicans, clearly below the estimated 31% that Bush received in 2000 and the 40% he received in 2004. Lionel Sosa, an adviser to Karl Rove and President Bush on the development of their Latino strategy stated that because the Republican Party positioned itself as the anti-immigrant party “we as a party got the spanking we needed.”17

Any short-term gain for the GOP that may lay in anti-immigrant rhetoric could come with a serious potential long-term cost. The Republican Party may have alienated itself from a generation of Latino voters. Polls of Latino voters show overwhelming support for less punitive, more comprehensive immigration reform,18 and since the passage of Proposition 187 in California, Latino public opinion has generally drawn few distinctions between politics targeting immigrants and politics targeting Latinos in general. This has directly contributed to making California one of the most Democratic states in the nation with the party holding a considerable advantage among the ever-growing Latino electorate there.19

According to the 2006 American Community Survey, 86.2% of all Latinos under the age of eighteen are U.S.-born citizens. The percentage equals approximately 13.4 million future eligible voters. The current population of eligible Latino voters is approximately 17.6 million. Thus, the size of the Latino electorate will increase by as much as 75% in the next two decades even without a single additional immigrant entering the United States or becoming a naturalized citizen. Recall that most of these new voters are within a single generation of the immigrant experience.

The evidence from public opinion surveys does not appear to support the severely restrictionist view. Americans have a remarkable level of consensus on the immigration issue. That consensus is generally drowned out by the shouting coming from the extremes on either end, but the level of agreement is generally pretty high. In a Los Angeles Times/Bloomberg Poll in June 2007, 63% of respondents favored a multifaceted approach that addressed both border security and the long-term status of immigrants already living in the United States.20 By contrast, there is little support for the expulsion or criminalization approach advocated by HR 4437. When asked about providing a path to citizenship for undocumented workers that includes fines and requirements to learn English, 60% of respondents in a December 2007 poll favored this and only 15% opposed.21 Tamar Jacoby of the Manhattan Institute argued that this popular consensus can serve as the foundation for leaders in both the Republican and Democratic parties to build the legislative consensus that can produce needed reform in our immigration policy.22 The greatest risk that the nation faces in continuing to cater to the divisiveness in much of the immigration debate is a missed opportunity to help the nation move forward on this complex issue.

The stalemate that national policymakers face regarding immigration policy poses another risk: a hodgepodge of state and local immigration policies that serve to further fuel anti-immigration views. In 2006, for example, many states and cities passed their own laws and ordinances restricting the rights of unauthorized immigrants, their landlords, and their employers. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures at least fifty-seven specific laws were enacted by states regarding unauthorized immigrants, including laws that

• prohibited the awarding of state contracts to businesses that knowingly hired unauthorized workers (Colorado);

• fined employers with state contracts who did not fire workers who were known not to have appropriate documents (Louisiana);

• required public employers, government contractors, and subcontractors to verify the work status of all new employees through a federal program (Georgia);

• authorized the training of seventy state troopers to arrest unauthorized immigrants (Alabama);

• prohibited unauthorized immigrants from receiving state services such as adult education, child care, in-state tuition, and punitive damages in civil lawsuits (Arizona);

• prohibited the use of unauthorized immigrants on state projects (Pennsylvania);

• prohibited businesses from deducting the costs of salaries and benefits for unauthorized workers from their taxable revenue (Texas); and

• sent troops to the border with Mexico (Arizona, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Wisconsin).

Ann Morse of the National Conference of State Legislatures stated, “The trends… have leaned toward the punitive side. The No. 1 topic has been employment in terms of deterring employers and employees.”23

A number of cities have passed local ordinances similarly designed to punish employers and landlords. The city council in Hazelton, Pennsylvania, voted to enact the Illegal Immigration Relief Act, which “would deny licenses to businesses that employ illegal immigrants, fine landlords $1,000 for each illegal immigrant discovered renting their properties, and require city documents to be in English only.”24 Farmers Branch, Texas, a suburb of Dallas, passed ordinances in 2006 that fined landlords who rented to unauthorized immigrants, gave police the authority to seek certification to act as agents of the Department of Homeland Security, and declared English the city’s official language.25 The fine for landlords was $500 per tenant per day. In Escondido, California, the city council gave landlords ten days to evict unauthorized immigrants and made landlords subject to “fines up to $1,000 a day, six months in jail, [and] suspension of their business license.”26 Each of these actions can be understood as a direct response to the perceived unwillingness and inability of the national government to do its job. State and local action represent new stakeholders and decision makers, who will act on the basis of how they do or do not see their interests served in the current immigration debate.

The current restrictionist immigration regime is also doomed to failure because it does not recognize that current population and labor migration are inevitable in the increasingly globalized international economy. The standard of living in developed nations is increasingly linked to its relations with the developing world. Among the primary causes for the growth in both authorized and unauthorized migration to the United States from Latin America is the increasing growth and privatization of Latin American economies, often driven by requirements of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The workers cannot find adequate employment in their home countries. Limited job growth in developing economies is likely largely driven by job losses in traditional sectors and efforts by employers to be more efficient and competitive in the global marketplace. Sociologist Doug Massey and colleagues state, “International migration does not stem from a lack of economic development, but from development itself…. The fact of the matter is that no nation has yet undergone economic development without a massive displacement of people from traditional livelihoods, which are mainly located in the countryside; in the vast majority of cases a large fraction of these people have ended up migrating abroad.”27 Massey and his colleagues provide considerable evidence of how this has directly affected the waves and magnitude of immigration from Mexico to the United States since the 1970s.

If labor migration is inevitable, should not the United States work with this inevitability rather than act as if immigration policy can be understood only as a law enforcement issue? Moreover, what would be the impact of restrictionist policies on Mexico and Central America if remittances fell owing to increased repatriation and deportation of unauthorized workers? It seems likely that the increased hardship and demands for government support from lower income families and communities in sending countries would increase. If these countries were unable or unwilling to meet these demands, political instability would result, raising the incentives for workers and their families to migrate to the United States. Policy informed by a cycle of misinformed analysis would, in the long term, serve no one’s interests.

Rogers Smith has argued that to understand the evolution of America’s laws regarding citizenship, with direct implications for the development of “American civic identity,” one has to appreciate the critical role played by elected leaders in positioning themselves on who should and who should not be included in the body politic. This is necessary to gain favor with minimum winning coalitions of voters. He states, “First, aspirants to power require a population to lead that imagines itself to be a ‘people’; and, second, they need a people that imagines itself in ways that make leadership by those aspirants appropriate. The needs drive political leaders to offer civic ideologies, or myths of civic identity, that foster the requisite sense of peoplehood, and to support citizenship laws that express those ideologies symbolically while legally incorporating and empowering leaders’ likely constituents.”28 As we first saw in chapter 3 of this volume, among the most effective ways that this has been done over the course of American history has been through the simultaneous empowerment of certain segments of the American public and marginalization of other segments. The definition of a legitimate American, with the formal capacity to make claims on the state, has grown over time to include those who did not own property, former slaves, women, immigrants, and their ethnic progeny. However, the political consensus that made these expansions possible was often driven by the fact that these expansions did not include everyone. The current immigration debate presents the United States with another opportunity to decide this question that is so central to the continued evolution of American national identity and that is driven by concerns over Latin American immigrants.

The options U.S. political leaders present to the American public, the political leaders the American public chooses to support, and who therefore will be included in the changing contours of American national identity will have direct implications for Latin American immigrants, current Latino U.S. citizens, and future Latino U.S. citizens. The direction of this debate is, as of this writing, unclear. What cannot be disputed is that all Americans, including Latinos, and all Latin American immigrants, including those who are authorized and those who are unauthorized, have clear interests in directly engaging in these debates. Vitriolic rhetoric on any side is unlikely to serve the nation’s long-term interests. What is most clear is that the outcome of that debate will be served only if all involved commit themselves to honest, transparent, evidence-driven analysis, discourse, and argument. Only then does informed decision making have any chance of moving us toward comprehensive immigration reform.