As we have demonstrated, there is no shortage of policy proposals to deal with the “problem” of illegal immigration. What is in short supply is any agreement on which of the many proposals currently in play is superior to the rest. The range is striking.

1. At one extreme we find proposals for forced mass repatriation—the “round them up and bus them back” position of the Tom Tancredo/ Minutemen kind.

2. Next to that, more widely canvassed, is the policy of selective raids by teams of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) inspectors: the policy of vigorously enforcing existing immigration legislation by the arrest and deportation of illegal immigrants—or, as in Mississippi, giving them up to five years jail time ahead of deportation—a policy that has the added bonus, for those who advocate it, of creating such conditions of fear in the immigrant community that other illegal immigrants are induced to return home voluntarily.

3. Widely canvassed too, in conservative circles at least, is another strategy designed to induce voluntary repatriation. It is a policy of attrition: designed to deny illegal immigrants any welfare or civic rights—no drivers’ licenses or health care, no education for their children, and certainly no automatic citizenship for their babies born here.

4. These first three “solutions” tend to sit alongside renewed calls for tighter border security and the building of actual walls, border fences, to cut off the flow of illegal immigrants at the source.

5. To achieve that same objective with or without walls, many people also advocate the careful verification of documents relating to citizenship, the creation of new documents if necessary, and fines or imprisonment or both for employers who provide work for immigrants without such papers.

6. The fact that many employers need those workers regardless of their legality has led others to advocate the expansion of guest-worker programs and the more generous provision of temporary work visas, targeted toward industries particularly dependent on low-wage temporary labor.

7. The fact that so many temporary illegal workers are already here, and the sheer difficulty of rounding them all up, has induced more liberally minded policy advocates to seek routes to legality for them—either (a) by offering them legal status in return for an obligation eventually to return home or (b) by designing mixtures of fines and language training as a prerequisite for entering the naturalization process, or (c) by requiring that illegal immigrants return home for shorter or longer periods of time and then reenter through legally established and publicly supervised “ports of entry.”

8. Ultimately that opens the way to proposals for a general amnesty for undocumented workers already here;

9. calls for visa reform (expansion in the number of legal visas and the speeding of their distribution); or

10. comprehensive packages that brings together in some fashion either proposals 4–8 or proposals 5–9.

This range is not one that sits easily on existing party divisions. On the contrary, the range creates divisions within the existing parties rather than between them; although the center of gravity of the debate in each party is significantly different. There is a populist wing of the Democratic Party that is keen on proposals 1–5, and trade union pressure within the party is normally directed against guest-worker programs (proposal 6). But in general, leading Democrats tend to advocate some mixture of proposals 5–9, and to be particularly critical of policies that deny welfare rights to illegal immigrants already here or that include the building of walls. Yet it is precisely those policies that appeal most strongly to wide sections of the Republican Party base, a base that felt actively betrayed by the Bush administration’s support for guest-worker programs and a more porous border. The dispute within the Republican Party on immigration of late has been deep and bitter; so bitter, in fact, that in 2006 bipartisan attempts at comprehensive immigration reform focused on guest-worker programs and routes to legality foundered for that reason alone. Anti-immigration forces mobilized against the bipartisan bill passed in the Senate, warning of defeat in upcoming primaries for lawmakers who strayed from the new orthodoxy of “securing the borders first.” Likewise, in 2008, an election year whose first half was dominated by party primaries, no major Republican candidate was able to advocate renewed bipartisanship without paying a fatal electoral price.

For that reason we currently face two broad policy choices. One—the Republican option adopted by John McCain in contrast to that earlier advocated by President Bush (and by McCain at the time)—seeks to solve the immigration problem primarily by sealing the border, enforcing existing laws, and denying any route to citizenship for illegal immigrants already here. Leading Republicans, that is, have united around a “no amnesty” package that sometimes does (and sometimes does not) also include a temporary worker program. The Democratic Party leadership, by contrast, remains committed to a package of measures broadly similar to that pursued intermittently by the White House after 2001. It remains committed to the expansion of guest-worker programs, to the establishment of routes to legality for undocumented workers already here, to tough sanctions on employers who continue to recruit undocumented workers, and to a strengthening of border security. The two packages overlap, but their centers of gravity are quite different.

The debate rages in part, and no one proposition prevails, because each of the major alternatives in play has a downside that is evident to those advocating some or all of the rest.

Mass forced repatriation is repugnant to many because of its impact on those caught up in that repatriation and on the local communities from which the illegal immigrants would be plucked. For it to work, elements of a police state would need to be created in the United States: a system of neighborhood spies, an inflated immigration secret police, large holding areas with Guantanamo Bay–like connotations, and a fundamental erosion of civil liberties. The cost in money—as well as in rights and international reputation—would simply be too large. And doing it on the cheap—by merely increasing the number of ICE raids—is equally offensive to many. It does indeed create a climate of fear in the immigrant communities that are targeted. But it also reinforces racism in the society doing the targeting, and its results—arrests in the night, the separation of parents from children, the sudden destitution of those left behind—is anathema to many activists within the Latino community, the Catholic bishops (including the Pope), and many trade union and Democratic Party activists. To their critics at least, proposals 1 and 2 are simply incompatible with core American values. They smack of the Gestapo in the 1930s, and America does not do “raids in the night.”

By the same token, the systematic denial of welfare and education to illegal immigrants and their children sits in tension, for many, with basic American principles of equality and decency: in tension with the belief that everyone living and working in the United States has a set of basic rights that must be honored and in tension with a society that believes that among those rights are access to emergency medication and proper education. Are we really going to turn the sick away, or heal them just so that we can deport them when healthy? Because if we are, illegal immigrants will stay even farther away from medical treatments that they need, adding to the long term health risks of everybody with whom they come into contact. The adverse consequences on legal immigrants that flow from the denial of rights to the undocumented are always much in evidence when this “squeezing-out” strategy is publicly debated. Where is the sense, critics ask, in denying drivers’ licenses to illegal immigrants, when that denial cuts them off from access to car insurance and keeps them away from any relationship with law enforcement? It is a trigger to a spate of hit-and-run accidents that leaves everyone else more vulnerable to injury and destruction, not less. And where is the gain in denying the children of undocumented workers access to the education that is so vital to their (and our) long-term competitiveness and prosperity? Where is the sense in cutting off our nose merely to spite our face?

Then there is the issue of the wall. Its critics claim that building a wall to keep people out will be ineffective and can actually be counterproductive. It is costly, and the cost in no way matches the gain. Walls merely redirect the immigrant flows. They go under the walls or around them. Walls alone do not deter, but they do trap. Whenever Latino undocumented workers are surveyed, as many as 70% say they wish to return to Mexico after a temporary stay in the United States. Durand and Massey have noted, “Left to their own devices, most Mexican immigrants would work in the United States only sporadically and for limited periods of time.”1 They come to make money to take home. But walls stop that circular flow. Instead of working as intended, walls have a string of perverse consequences.2 The construction of walls both triggers immigrant flows and alters their demographics. More people come ahead of the wall, slipping in before it is created. They come with their families because getting back to those families is now more difficult. So more women come. More children come. Fewer men return home. More migrants stay and then disperse. The one thing you don’t want to do with an itinerant population is create incentives for them to settle. Walls create exactly those incentives. They also drive immigrants toward ever more dangerous crossing points, escalating the numbers of those who are robbed and raped in the desert or who die there of exposure and lack of water.

Creating new documentation, and then fining employers who disregard the new tests for citizenship are not without their problems either. Critics of the use of biometric data to track foreign travelers point to the erosion of civil liberties created by the presence of documentation of this kind and to the cost—running maybe into the billions of dollars—of creating and maintaining any adequate electronic employer-verification system.3 Critics of less sophisticated paper-based systems of identification point to the ease with which such forms of ID can be counterfeited and to the danger of enforced unemployment for many law-abiding American citizens who, through innocent changes of name or clerical error, find themselves cut off from work because of their possession of “defective” Social Security documentation. The Social Security Administration currently has 435 million records, 18 million of which do not match.4 These mismatches cannot all be illegal immigrants, and even if they were all illegal, knowing that might not make the degree of difference required. After all, there is nothing particularly new about the proposal to fine employers. That proposal was a key element of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. It was an element that was never systemically implemented, and it will not be again because if it is whole industries will collapse, local economies will suffer, and the price of key commodities will soar—the price of Christmas trees for one, the price of basic fruit and vegetables for another.

Guest-worker programs seem a logical solution to much of this, but they too have their critics. Guest-worker programs are said to erode wages and jobs and slow the rate of technological change in the industries to which they are applied, and the guest workers themselves, tied as they are to a particular employment opportunity, are wide open to super-abuse by unscrupulous employers. There is plenty of evidence of that abuse,5 and of the ways in which the 1942–64 bracero program actually fostered the growth of illegal immigration.6 There is also evidence that even the threat of fining employers can make working conditions worse, not better. Apparently, the appalling working conditions experienced by Mexican labor on American farms actually deteriorated further after the 1986 act “criminalized the hiring of undocumented workers, causing employers in agriculture to shift to labor subcontracting and thereby substantially reducing the amount of money going to workers.”7 Guest-worker programs are said by their critics to “undermine the wages and working conditions of US workers; create dependencies among businesses for docile foreign workers with no voice, no bargaining power and few rights; and allow abuses that most Americans would denounce if they were aware of them.”8 They are also said to be singularly inappropriate in times of recession such as these and particularly unwelcome in industries in which unemployment is already high and wages flat. Yet, as the Economic Policy Institute has recently verified, these are the industries that are characteristically singled-out as ideal for guest-worker expansion.9

Offering routes to legality for undocumented workers already here does at least bring them out of the shadows: giving them access to law enforcement and basic social services that might otherwise be denied or, even worse, provided by criminal elements already entrenched within the immigrant community. But to offer such a route makes a mockery of our immigration laws. It denies Americans the right to decide who can come into the country and on what basis. It also penalizes those would-be immigrants who stay within the law, waiting patiently at a port of entry for permission to come. Illegal immigration is queue-jumping, big time. And the more that legislators try to limit that queue-jumping by making the fines heavier and the conditions of entry and reentry more onerous, the more they build in incentives for the undocumented to remain undocumented: pushed beyond the reach of law twice—once by their decision to come and once by the severity of the processes they must undergo to change their legal status here.

According to its critics, amnesty sends exactly the wrong signal to would-be illegal immigrants. It says—come! Once here, you will be able to stay. Do not wait to be processed. Just arrive. Particularly, do not wait for visa reform. The volume of people wanting to come to the United States is so large that any immigration service would be overwhelmed by it. Extra resources going into the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (UNCIS, formerly the Immigration and Naturalization Service) are resources that could be used internally on the hospitals and schools overburdened by the demands of illegal immigrants who have already penetrated our porous southern border. To grant amnesty, to expand the USCIS—so the argument runs—is to allow immigrants to set immigration policy. Immigration policy should be determined by Americans. We have too many unskilled illegal workers here anywhere. We do not need more. We do not need to legitimize those who have already come. Either we need no more immigration for a while, or we need a different kind of immigration, one more sensitive to the skills people can bring to our competitively besieged economy. Either way, immigration policy is not to be fixed by foreigners crossing our borders. It should be fixed by us. That, at least, is the argument.

So how should we go forward in the face of all this dissent? First, by going back—back to the question of why undocumented workers come to the United States—back to why they come, why they come without papers, and why they stay.

The first thing to grasp in answer to those questions is that Mexican migration, legal or otherwise, is currently—as Mark Miller showed so clearly in chapter 2—only one part of a truly global phenomenon. People are on the move in significant numbers in many parts of the global system: sometimes for reasons of political persecution, war, and family reunification but, more normally, as with people leaving Mexico, for purely economic reasons. According to Martin Wolf, “At least 160 million people were living outside their country of birth or citizenship in 2000, up from an estimated 120 million in 1990.” Only five countries on earth have a population that exceeds 160 million, and 160 million people is one human being in every thirty-five. The Mexican-U.S. exchange of migrants is currently the world’s largest, but it is by no means the only one. The United States’ 35 million foreign-born workers stand alongside Russia’s 13.3 million, Germany’s 7.3 million, and Ukraine’s 6.9 million.10

“The fundamental problem with U.S. immigration policy towards Mexico—and with U.S. immigration policy generally—is that,” as Douglas Massey has argued, “it treats international migration as a pathological condition to be repressed through unilateral actions. In reality, immigration is the natural outgrowth of broader processes of market expansion and economic integration that can be managed for the mutual benefit of trading partners.”11 Successive administrations in Washington, D.C., have been ardent advocates of globalization and free trade. The movement of labor across national borders is not qualitatively different, in economic terms, from the movement of capital and goods. Migration is labor’s equivalent to the export and import of investment funds. So there is something profoundly paradoxical about governments in advanced industrial societies advocating open markets and the free movement of capital—not to mention tolerating systematic outsourcing and deindustrialization—while insisting at the same time that labor stay put. This paradox is at its most acute in U.S. relations with Mexico. Massey wrote, “Since 1986, U.S. officials have worked closely with [Mexico and Canada] to create an integrated North American economy, open to flows of goods, capital, commodities, services and information. Yet within this integrated economy we somehow, magically, do not want any labor to be moving.”12

Moreover, to those critics of illegal immigration from Mexico who put the weight of their criticism on its adverse impact on wages and jobs, it must be pointed out that they are focusing their attention on the wrong migration. As we saw in chapter 6, the movement of 11 million Mexican workers across the southern U.S. border has at most only a marginal impact on the wages and job prospects of native-born unskilled labor. The movement of 150 million Chinese agricultural workers off the land and into the export factories of China’s pacific provinces has, by contrast, a huge effect on the wages and employment prospects of the American poor. It is that migration that is deepening U.S. poverty, not the relative modest flow of Latino labor. If, therefore, we are genuinely determined to protect low-wage American workers from the “burden” of migration, it is to our policy with China that we might more productively turn.

But why, if that is so, do Mexican workers brave the Arizona desert for the right to earn low wages for hard work north of the border? In part they do it—as Peter Siavelis argued in chapter 7—because Mexican wages are significantly lower even than low American ones, so coming north is a quick way of accumulating enough cash to participate in, for example, the Mexican housing market—a market in which domestic lending arrangements are still significantly underdeveloped.13 Partly, they do it because Mexican economic growth, so impressive relative even to U.S. rates from the 1940s to the 1980s, has been equally unimpressive in the last two decades. In part they come as a consequence of differential birth rates: the Mexican baby boom occurred at least two decades later than the American one, so there are spare bodies around; and they come illegally, of course, because the U.S. abandoned its Mexican guest-worker program (the braceros program) in 1965 and replaced it with a national quota for the first time in the Mexican case. Relative to the number of Mexican workers wanting to come north, the quota was and is very small.

The drivers and underlying dynamics of the movement of people north across the Mexican-American border have to be grasped in their totality if effective policy is to be designed to slow or manage that movement. If would-be migrants simply do an immediate cost-benefit analysis, then toughening the costs (wall building, strengthening employer sanctions, and increasing rates of arrest and deportation) makes perfect sense. But if, as Massey and Espinosa have found, things are otherwise—that the calculations are infinitely more complex and nuanced than that—then policies of forced exclusion may actually be counterproductive. Massey and Espinoza’s careful empirical work has demonstrated that, contrary to popular views, illegal immigration “does not appear to be driven much by the lure of high wages or generous benefits north of the border, by the forces of inflation and devaluation in Mexico, or by poverty or a lack of development in sending communities.”14 Even greater risks of apprehension at the border have only a minor impact on illegal immigration flows. Interest rates rather than wages appear to be the more significant macroeconomic driver here: “as they go up, circulation within the migration system accelerates: more Mexicans leave for the United States to gain capital, and more migrants return to Mexico to invest [often in house purchase] what they have saved.”15 As they put it, “The dynamic expansion of migration between Mexico and the United States does not follow from simple change in the objective costs and benefits of international movement but from the operation of self-perpetuating, interlocking, and mutually reinforcing processes of social capital formation, human capital formation, and market consolidation. Rather than discouraging these forces, the thrust of U.S. policies in recent years has been to amplify and reinforce them.”16

If Massey and Espinosa are right, illegal immigration across the Mexico-U.S. border increases when earlier generations of the same family have already migrated. Illegal immigration quickens when the number of legal visas is reduced and when the prospect of tougher border sanctions looms. Immigration quickens when denser market relationships between the two economies break up traditional patterns of work and kinship in rural communities and generate rising unemployment there. Whether or not that migration is then “observed as legal or illegal depends largely on the supply of visas made available by the United States and by the number and range of kinship ties that Mexicans have to legal resident aliens and U.S. citizens.”17 Militarizing the border has not stopped any of that. Rather, “it has transformed a seasonal movement of migrant labor in three states into a settled population of immigrant families dispersed throughout the country.”18 Conservative politicians are always telling us to leave things to the market, that state intervention only disturbs natural processes and produces suboptimal consequences. They are not always right, but in relation to labor movement back and forth across the southern border—as the libertarian Cato Institute, among others, regularly remind them—they have a point. It is one they would do well to take to heart.

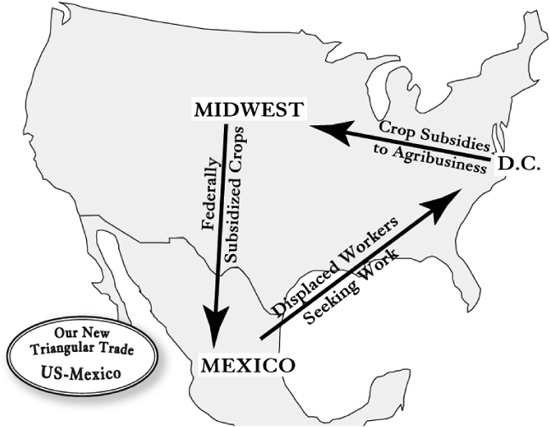

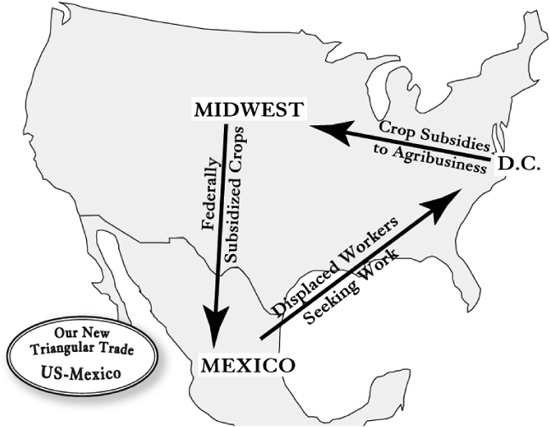

FIGURE 14.1. OUR NEW TRIANGULAR TRADE: U.S.-MEXICO

In this regard, it is also important to recognize that the bulk of the present crop of illegal Mexican immigrants has come to the United States since 1994 and has done so from rural provinces. Contented farmers do not easily leave their land, but Mexican agriculture has shed labor on a large scale since 1994, as the incremental implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement’s terms exposed more and more small-scale Mexican farmers to fierce competition from American agribusiness. As Peter Siavelis argued more fully in chapter 7, NAFTA established a developing competitive floor between the farmers of two countries, but it did not establish a level one. On the contrary, it opened a competitive battle between a farm sector south of the border where the average annual subsidy is $720 and a farm sector north of the border where the average annual subsidy is $20,000.19 And that average obscures the privileging of agribusiness within the North American agrarian sector, a privileging that makes the imbalance between the two agrarian economies steeper still. Congress was unwilling to pass comprehensive immigration reform in 2007, but in 2008 it did push through a renewal of the 2002 Farm Bill—a renewal so generous that even a Republican president threatened to veto it. U.S. federal authorities are currently subsidizing crop production to the tune of $25 billion annually, with a staggering 73% of that money going to just 10% of all U.S. farmers, and 90% of it subsidizing just five crops: wheat, cotton, corn, soybeans, and rice.20 In the U.S. system, “the biggest farms get the biggest subsidies”21 and small-scale Mexican farming pays the price.

So while there is legitimate dispute about NAFTA’s impact on American jobs, what is clear is NAFTA’s inability to prevent rising unemployment south of the border or to prevent the widening of wage differentials between the two economies.22 Though particular sectors of the Mexican economy visibly benefited from the trade agreement, small-scale farming definitely did not. On the contrary, since 1994 peasant agriculture in Mexico “has been eviscerated by the arrival of agribusiness and the lifting of restrictions on the sale of peasant land” as industrial employment there “has been eviscerated by the closure of hundreds of plants unable to compete with the trans-nationals under the new free-for-all trade regime.” Since 1994 U.S. corn exports to Mexico have risen eighteen-fold. During those same years, 2 million Mexican farmers have left the land, and the incidence of rural poverty has risen by 10 percentage points.23 In the wake of NAFTA a new iron triangle has opened up (see figure 14.1).24

Vast numbers of tax dollars flow west from Washington, to subsidize large-scale corn production. That corn production flows south, across borders opened by NAFTA, displacing small-scale Mexican farmers as it does so. Mexican labor then flows north, picking its way across a border open to capital and commodities but not to people: with more tax dollars spent trying to keep them out. The signing of NAFTA and the escalation in the scale of illegal immigration are thus intimately linked: as Alejandro Portes observed, “The response of peasants and workers thus displaced has been clear and consistent: they have headed north in ever greater absolute numbers.”25 Perhaps as many as 600,000 of those displaced farmers “became NAFTA-caused additions to the normal flow of indocumentados seeking employment in the United States” after 1994.26

So, as we design policy to “solve” illegal immigration, we do well to remember the degree to which we are, partially at least, the architects of the immigration flows we now seek to “solve.” That Mexican immigrants come at all is a product of demand for their labor in the north. That they come in such volume now is a product of the degree to which we still subsidize our large-scale agrarian producers. That they come illegally is a product of the absence in the north of visas and guest-worker programs of a scale that can accommodate them all. If we are to tackle illegal immigration effectively, we need to tackle it at its source. The underdevelopment of both the Mexican economy and U.S. visa systems for unskilled labor are two of those sources. Oversubsidized American agriculture and low-wage American industries are two others.

Faced with multiple causes and conflicting solutions, it is impossible to avoid the question of choice; and because it is, we do well to make our choices only when keeping those multiple causes in mind.

Ethnic cleansing is always a solution to labor market overcrowding. It is always possible to push people over the border and wash our hands of the consequences of our action on their conditions of existence. It is always possible to stay focused on only the interests of the native-born and to persuade ourselves that excluding illegal immigrants is the best thing we can do for the American poor. Self-delusion is an important skill in politics, but it is still self-delusion. In any case, there is something profoundly distasteful in the sudden enthusiasm of the American Right for the economic well-being of the native-born poor, particularly the well-being of its black sections. The native-born poor, especially the black poor, have been present and visible in the United States since Reconstruction. Every attempt to organize them—from populism in the 1890s to the civil rights movement of the 1960s—has been vehemently opposed by the political forces that now present themselves as the champions of the American poor against the imported poor of Mexico. Epiphanies are always wonderful things to witness, but this one looks far too contrived. If we want to end low wages in America, we can end them. We can set a high minimum wage. We can issue more generous earned income tax credits to bolster that minimum, and we can tax the rich to pay for both. We can also stop the dumping of cheap Chinese goods in U.S. markets and insist on high labor and environmental standards and rising wages in Chinese factories. We don’t need to focus on immigration to solve poverty in the United States. Illegal immigrants make an easy scapegoat: but scapegoats are not causes. The causes of poverty lay elsewhere and need to be tackled not by building a bigger and bigger wall but by introducing fiscal policies of an explicitly redistributive kind and trade policies that privilege trade that is fair over trade that is free.

Treating illegal immigration as something to be repressed quite simply does not work. The findings of the Mexican Migration Project make that abundantly clear.27 Tougher U.S. enforcement does not deter Mexican migrants from coming north. It does, however, discourage them from going back. It builds in incentives for more dependents to come and for more to seek naturalization (with the associated capacity to bring even more family members later). Tougher U.S. enforcement policy has, and will continue to have, entirely perverse consequences, transforming “what had been a relatively open and benign labor process with few negative consequences into an exploitative underground system of labor coercion that put downward pressure on the wages and working conditions not only of undocumented workers but of legal immigrants and citizens alike.”28 Whatever else we need, we do not need policies that privilege forced repatriation, border closure, and intensified raids by ICE.

The illegal dimension of our present immigration condition does need addressing.

• There has to be an incrementally introduced employer verification program and the subsequent sanctioning of companies employing undocumented labor.

• There has to be a route back to legality for workers already here illegally, and that route has to be an earned one.

Back-taxes, a fine, English-language lessons, participation in temporary worker programs—all make a certain kind of progressive sense, but only if set in the context of other changes too.29 Five spring to mind:30

1. One is the introduction of a radically reformed guest-worker program to bring together industries in need of seasonal labor and labor eager to go home once those wages have been earned.31 The temporary work visas should be given to the workers themselves, not tied to a particular job, thus freeing the temporary labor from total dependence on one employer. The number of such visas should be tightly controlled, and the visas should only be issued after a full nationwide job search has been implemented by the employers requesting them.

2. The establishment of a high minimum wage and enforceable minimum labor standards in the industries affected, to block off sweatshop conditions and super-exploitation. (The Economic Policy Institute suggests that American workers in these industries be paid at least 150% of the U.S. minimum wage, regardless of the prevailing wage, to see whether immigration is necessary or whether native-born unskilled labor will suffice.32)

3. A far larger quota for legal Mexican immigration, with an enhanced capacity to process applications rapidly (so that those going through the legal mechanisms are not disadvantaged relative to those who braved the southern border illegally and at night).33

4. What Audrey Singer has called an impact aid program: federal funds to offset local and state expenditures linked to heavy concentrations of undocumented immigrants (so taking the sting out of much anti-immigrant opposition at the community level).34

5. Finally, a complete overhaul of the financing of large-scale U.S. farming to ensure a more level playing field between agricultural sectors on each side of the border. A revitalized Mexican farm sector is a vital prerequisite for a restoration of Mexican economic growth. It is that growth, and that growth alone, that ultimately can bring the movement of peoples across the southern border back to a manageable and desirable level.

No sane society leaves the question of its membership to either the accident of history or the immediacy of the market, but by the same token, no civilized society condones one code of behavior in its hinterland and quite another on its borders. All modern societies have a right to develop policy on immigration, and ideally, the current debate on that policy here would be focused exclusively on whom to admit, not whom to expel. But we have allowed illegal immigration to occur on a massive scale, and that immigration can be neither wished away nor easily reversed. Societies without our democratic values might find it easy to repatriate millions of hardworking people, but we should not find it so. A society like ours—one built on immigration—has a particular responsibility to deal with undocumented workers and their dependants in a manner consistent with the way in which earlier generations of Americans dealt with the arrival of our forebears. And a society that honors 1492 as a founding moment in its own history has a particular incentive to find ways of absorbing—rather than expelling—those who arrive here without the native population’s permission. The world is already too scarred by cultural intolerance and ethnic closure to need any more of either. This is not the moment for the United States to seal its borders against the coming of the brave. It is the moment for the United States to live up to its promise as the land of the free.