1 ULTIMATE COFFEE

ESPRESSO DEFINITIONS

At the level at which we genuinely live life, every reader of this book will have a different definition of espresso. For some, that definition may be a long-developed acquaintance with the beverage, an accumulation of happy memories of caffès and tinkering with home machines, of frothed milk and crema. For others “espresso” may mean a single experience with a caffè latte taken at an outdoor espresso stand during a vacation, or a couple of cappuccinos drunk while on a trip to Italy. Like coffee itself, espresso is as much an experience caught up in the intimate textures of our lives as it is a beverage.

Yet even when we attempt to define espresso in more detached fashion, there still appear to be many overlapping definitions, rather than a single, all-inclusive one.

A TECHNICAL DEFINITION

A definition of espresso along technical lines is perhaps least ambiguous: Espresso is coffee brewed from beans roasted medium to dark brown, with the brewing accomplished by hot water forced (or “pressed”) through a bed of finely ground, densely compacted coffee at a pressure of over 9 atmospheres, or nine times the normal pressure exerted by the earth’s atmosphere. The resulting heavy-bodied, aromatic, bittersweet beverage is often combined with milk that has been heated and aerated by having steam run through it until the milk is hot and covered by a head of froth.

To extend the technical definition somewhat, we might say that espresso is an entire system of coffee production, a system that includes specific approaches to blending the coffee, to roasting it and grinding it, and that emphasizes freshness through grinding and brewing coffee a cup at a time on demand, rather than brewing a pot or urn at a time from pre-ground coffee and letting the result sit until it is served.

A HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL DEFINITION

Defining espresso culturally and historically is more problematic. The taste for a dark, heavy, intense coffee, sweetened and drunk out of little cups, is obviously much older than the espresso machine itself, and may stretch back as far as the first coffeehouses in Cairo, Egypt, established during the early fifteenth century. On the other hand, technology (and the imagery of technology) is also obviously an important element of espresso culture. Although all coffee making lends itself to technological tinkering, no other coffee culture has applied technology to coffee making with quite the passion as the Italians have to espresso. The word “espresso” itself suggests custom brewing, as in brewed expressly for you, as well as direct, rapid, nonstop, as in express train. Not only has technology been applied enthusiastically to the actual process of brewing espresso, but the imagery of technology, the idea of modernity and speed, also turns up as a major element in espresso’s cultural symbolism. See the famous Victoria Arduino poster from the 1920s here, for example.

So culturally and historically we have a paradox. On the one hand, espresso as a general taste in coffee drinking goes back to the very beginnings of coffee as a public beverage. On the other, Italian espresso culture has refined that taste through a technology that flaunts its modernity.

When we turn our attention to the United States, a historical and cultural definition of espresso might emphasize still another set of connotations. Rather than being associated with modernity and a dynamic urbanism, espresso in America has become identified with various alternative cultures, from Europeanized sophisticates nostalgically evoking tradition, to intellectual rebels attacking it.

ESPRESSO AS CUISINE

Espresso also can be defined as a kind of coffee cuisine. For example, mainstream American coffee cuisine emphasizes the bottomless cup: large, repeated servings of usually brisk-tasting, light-bodied coffees prepared by the filter method, often taken without milk or sweetener. Espresso cuisine, on the other hand, emphasizes smaller servings of heavier-bodied, richer coffee, brewed on demand rather than in batches, usually drunk sweetened, and often combined with frothed milk and other garnishes and flavorings.

In Italy the classic espresso cuisine emphasizes simplicity: perfect short pulls of espresso and a handful of exquisitely modulated combinations of coffee and milk. Predictably, in North America a more freewheeling, idiosyncratic, bigger approach has evolved. At one extreme the Seattle-style espresso cuisine rears its many-flavored head: wide open, innovative, the basic themes of espresso and milk exuberantly elaborated with flavored syrups, ice, a score of garnishes, and seemingly endless refinements involving the milk (1 percent, 2 percent, 4 percent, skim, soy, eggnog …). At the other is beatnik espresso, the original Italian-American cuisine, the espresso of storefront shops in old Italian neighborhoods and seedy artists’ caffès. This cuisine resembles the classic Italian, but the coffee is darker, the servings are bigger, and the taste is rawer. Between the two are a few, very few, caffès that conscientiously pursue the classic Italian ideal. The Cuban tradition of southern Florida constitutes still another, though more regional, American espresso cuisine.

Finally, there is still another American cuisine, which I would like to dub espresso manqué, and which is all of the misinterpretations and misunderstandings of espresso being committed in the United States today thrown together, including watery, bitter, overextracted coffee, scalded milk, meringuelike heads of froth, all presented to the background flatulence of canned whipped cream being sprayed on top of the drink to distract us from the grim reality underneath.

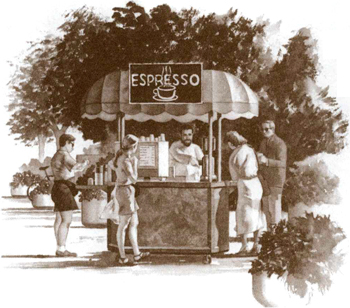

A DEFINITION BY PLACE

Finally, espresso can be defined in terms of the places it has helped create and that helped create it: the caffès, cafés, coffeehouses, espresso bars, and espresso carts of the world. For espresso is a quintessentially public coffee. The technological sophistication of the espresso system only could have evolved in the context of public establishments with enough coffee drinkers to support the expense involved in maintaining such large and complex coffee-making equipment. Thus espresso and the espresso machine have come to constitute the spiritual and aesthetic heart of a variety of subtly different institutions, including the Italian-American caffè, the espresso bar, the American coffeehouse, and now the Seattle-style espresso cart and stand.

THE NICE VICE

I’m drawn to add still one more definition, something along contemporary sociological lines. For it appears that fancy coffees generally, and espresso cuisine in particular, have assumed a rather unique role in contemporary American life. It is a role that has led some commentators to characterize coffee (and caffeine) as the “nice vice” of the millennium, the one pleasantly consciousness-altering substance that has escaped (perhaps narrowly) from the censure heaped by a health-conscious establishment on alcohol, tobacco, and their various illegal alternatives. Certainly the current crop of college-age youth, a generation I find particularly attractive, has adopted coffee as a beverage and ritual of choice. Fifties-style coffeehouses are booming, and T-shirts and lapel buttons surface wherever younger people congregate, half seriously, half ironically celebrating coffee. “Espresso Yourself,” says one; “Coffee Is God” proclaims another.

So is everything else, the Buddhist might reply, but for some of us a particularly good case can be made for our favorite drink.

A contemporary espresso cart, an increasingly familiar sight in North American shopping malls, downtown streets, and even gasoline stations.

ESPRESSO BREAK

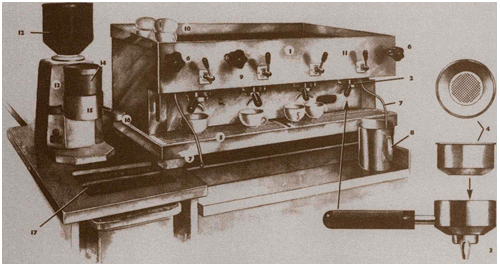

THE ESPRESSO BAR SYSTEM

Delivery of a tiny, aromatic cup of espresso or a perfectly balanced cappuccino depends on an integrated brewing system, including machine, grinder, and accessories. The various elements of a complete commercial espresso system are illustrated on the next page.

The machine. The machine pictured here is a simple semi-automatic pump machine. The operator or barista dispenses ground coffee into a metal filter fixed inside a filter holder, clamps the filter and filter holder into the machine, and presses a button to start and stop the flow of brewing water through the coffee. For illustrated descriptions of other types of machines, including manual piston and fully automatic, see here.

The housing (1) of the machine conceals a water reservoir, a pump to push the brewing water through the coffee, apparatus for heating and measuring the brewing water, and a boiler in which the water used to create steam for milk frothing is held and heated. The apparatuses that heat water for brewing and for making steam are separate, since the ideal water temperature for brewing is somewhat lower than the temperature required to produce steam.

The group (from Italian gruppo) or brew head (2) is where the filter holder or portafilter (3) and metal filter (4) clamp, and where the actual brewing takes place. See the cutaway illustration. The pump inside the housing delivers heated water through a perforated plate (shower head or disk) on the underside of the group, forcing the water through the ground coffee held in the filter and filter holder.

The filter and filter holder can be designed to produce a single or a double serving of espresso. If double, the filter is sufficiently large to contain twice the amount of ground coffee as a single, and the filter holder has two little outlets rather than one.

The drip tray (5) catches coffee overflow, and the steam valve or knob (6) controls the flow of steam through the steam wand, pipe, or nozzle (7), which the barista thrusts into the frothing or milk pitcher (8) to froth and heat milk for cappuccino, caffè latte, and other drinks that combine espresso coffee with hot, frothed milk. The hot water tap (9) dispenses hot water for tea and similar hot drinks, and the cup warmer (10) stores and gently preheats cups and glasses.

The illustrated machine has a very simple control panel (11). A switch above each group turns the brewing water on and off. With such machines the timing of the brewing operation is up to the barista. In machines with more complex controls the barista touches a button to select the length of the shot or serving of espresso (from a single short serving to two long servings). A computer chip does the rest. Controls for fully automatic machines may be even more elaborate, with more options, and may include readouts that provide the barista with information concerning brewing pressure, brewing temperature, and the like. For illustrated descriptions of more complex machines, see here.

On the other hand, manual piston machines (see here) provide no control panels or buttons whatsoever. The dose of brewing water is controlled by purely mechanical, nonelectronic means.

The grinder. Note the conical reservoir for roasted whole coffee beans (12), the grinding unit proper where the grinding burrs are concealed (13), the cylinder where the recently ground coffee is held (14), the doser (15), which measures one dose or serving’s worth of ground coffee at the flick of a lever, and the tamper, presser, or packer (16), which is used to distribute and compress the coffee evenly in the filter. Some bar systems may add a second grinder for decaffeinated beans, but if demand for decaffeinated drinks is light, the second grinder may be replaced, as it is here, by a simple container of preground decaffeinated coffee kept close at hand.

The bar. In addition to supporting the machine and grinder, the bar unit also includes a knock-out or dump box (17), into which the barista disposes spent coffee grounds by inverting the filter holder and knocking it sharply against the edge of the box. The knock-out box may sit atop the counter next to the machine, or it may be built into the structure of the bar, as it is here.