2 CULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY

ESPRESSO HISTORY

From a cultural point of view, the history of espresso extends back several centuries, to the beginnings of Mediterranean coffee-drinking tradition. If we look at espresso history from a more technical point of view, however, the horizon moves closer, either to the nineteenth century and the first use of the trapped pressure of steam to force water through a compressed bed of ground coffee, or to the mid-twentieth century, when Achille Gaggia introduced the first commercial machines to use a spring-loaded piston to force the hot water through the coffee at pressures even greater than could be achieved with trapped steam.

THE CULTURAL CONTEXT

Italians are wont to give the impression that the development of espresso was a purely rational, inevitable process, driven by technical factors alone, aimed at producing the best possible cup of coffee. However, the various North American and European technicians who developed the automatic filter-drip system might make the same argument for the process through which they perfected their brewing method.

Cultures and individuals choose to roast, brew, and drink coffee the way they do for reasons that are largely irrational. There is no intrinsic culinary logic or technical rationale for preferring “Turkish”-style coffee over espresso, for example, or for preferring either espresso or Turkish-style coffee over American-style filter coffee. Each of these coffee-drinking traditions represents a somewhat different cultural definition of “coffee.”

A Technical and Sensual Logic

It would seem, however, that once a culture has settled on a collective definition of coffee, a certain technical and sensual logic comes into play. Given the traditional North American definition of coffee, for example, we probably can say that automatic filter-drip coffee is “better” than percolator coffee, because given North American tastes the filter-drip coffee is brighter, clearer, and more aromatic than the percolator coffee, which has been perked to death, as it were. But I doubt whether a coffee drinker from either Yemen or Milan would consider either filter or percolator coffee much better than insipid hot water. Good espresso is neither bright nor clear like North American filter coffee, nor is it somewhat soupy and gritty like Turkish-style brew. Good espresso has its own, particular set of criteria for goodness.

The Idea of Espresso

So we must begin by tracing the taste for the kind of coffee that became espresso, for the idea of espresso, before we take up the technical developments that brought that taste or idea to perfection.

When coffee first made its appearance in human culture it was almost certainly as a medicinal herb in the natural medicine chest of the peoples of the horn of Africa, in what is now Somalia and Ethiopia. For until sometime in the fifteenth century, when Arab peoples in what is now Yemen learned to take this seed of a humble little berry, roast it, grind it, and combine it with hot water, it doubtless had little appeal to the human senses beyond its effect as stimulant. And even roast, ground, and brewed, coffee is a hard first sell to the taste buds. There is no evidence that I know of indicating that the human organism “likes” the taste of coffee at first encounter, although the aroma may have a natural appeal. Coffee, like many other beverages, appears to be an acquired taste.

Perhaps this is the reason that sugar was added to the cup fairly early in coffee’s history. The earliest accounts of coffee brewing in Arabia, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey seem to suggest that, although adding sugar or even milk (most likely goat’s milk) to the cup was not unknown, coffee was generally drunk either straight or with the addition of perfume or spice, most often cardamom. The “Turkish” coffee we are familiar with today, in which a finely powdered coffee and varying proportions of sugar are brought to a boil several times in a small pot, then dispensed into tiny cups, apparently took hold in the seventeenth century in Egypt and Turkey. This style of coffee, which eventually came to dominate the coffee cultures of the Middle East, North Africa, and Southeastern Europe, is drunk without separating the grounds from the coffee. The coffee is served very hot, and covered by a head of froth produced by the repeated boiling. By the time the liquid is cool enough to drink, the powdered coffee grounds largely have settled to the bottom of the cup, leaving only a slight, pleasantly bitter suspension of grit in the drink.

Although the differences between a demitasse of Turkish-style coffee and a demitasse of espresso may be rather striking, yet so are the similarities. In both cases, a rather darkly roasted coffee is drunk out of small cups; in both cases the coffee is heavy-bodied and usually taken sweetened; in both cases a good deal of emphasis is placed on the froth that covers the coffee (in the case of espresso the crema, in Turkish-style coffee the kaymak, to use the Turkish term).

Cow’s Milk and Strained Coffee

It is to Christian Europe’s love-hate relationship with the Ottoman Turks that we can attribute both the spread of coffee to Western Europe and the use of the term “Turkish” to describe a style of coffee now drunk over a large part of Eurasia and Africa. Tradition ascribes the habit of adding milk to coffee, which figures so importantly in North America’s growing love of espresso cuisine, to the failed siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1683. Franz George Kolschitzky, a Polish hero in the struggle, supposedly opened the first Viennese cafés with coffee left behind by the Turks after the siege was lifted. According to tradition, Kolschitzky first tried to serve his booty Turkish-style, grounds and all, but was forced to innovate by straining the coffee and adding milk to it before luring townspeople into the first of the famous Viennese cafés.

Historians have turned up earlier references to the use of milk in coffee, but in a real, cultural sense, legend is probably correct in attributing the beginning of the practice to Kolschitzky. Other coffee drinkers may have experimented with adding milk to their coffee, but the widespread, popular tradition of drinking strained coffee with cow’s milk probably did begin in Vienna in the seventeenth century, and spread from there into Western Europe. Meanwhile the areas of Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean that remained under Ottoman Turk control until later centuries (the Balkans, Hungary, Greece, Egypt, present-day Turkey, Lebanon, etc.) continue until this day to drink coffee in the “Turkish” style. This clear demarcation of coffee-drinking habits, with most people east of Vienna still taking their coffee Turkish-style with grounds, and most regions west of Vienna taking their coffee strained, often with milk, would seem to indicate that the innovation in coffee drinking that took place in Vienna in the seventeenth century was decisive in the history of coffee habits in Western Europe.

Coffee Comes to Italy

Coffee was first imported into Europe on a commercial scale through Venice beginning in the seventeenth century. As a consequence Venice developed Europe’s first coffeehouses, one of which, Caffè Florian (1720), is still extant, delighting tourists and lightening them of quantities of lire. Although Caffè Florian today serves the classic Italian espresso cuisine, with a latte or two thrown in for the North Americans, the early Venetian caffès almost certainly served coffee in the Turkish style, boiled with sugar and drunk with the grounds settled to the bottom of the cup.

It is doubtless the very powerful Austrian influence in northern Italy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that created a taste for filtered coffee and coffee mixed with milk. Austria controlled Milan, the ultimate center of espresso innovation, from 1714 to 1860, with only a brief interruption of French rule under Napoleon.

Still, it is tempting to see a lingering Turkish influence in the modern Italian obsession with crema, the finely textured brown froth that covers the surface of a well-brewed espresso. The culture of Turkish-style coffee puts a similar emphasis on the froth. In both the espresso and Turkish-style coffee cuisines, to serve coffee without a proper covering of froth is a sign of culinary impotence, bad manners, or both.

A Middle Eastern or “Turkish” coffee set. The object in the middle is the ibrik (Turkish) or briki (Greek), in which finely-powdered coffee, water, and (usually) sugar are brought to a foamy boil. The resulting strong, frothy suspension is poured from the ibrik into the little cups.

A nineteenth-century depiction of the Caffè Florian in Venice’s Piazza San Marco. Founded in 1720, The Caffè Florian was one of Europe’s first coffeehouses, and survives today virtually intact.

Nevertheless, it would seem that the Austrian influence is most important in the genesis of espresso, for although Italians continued to enjoy coffee strong, sweetened, and in small cups, the fact that they strained their coffee and often added hot milk to it is of the utmost importance in understanding the development of espresso cuisine.

Liberation of a Coffee Ideal

For it is on this cultural premise, i.e. a taste for coffee that is strong and heavy-bodied, yet filtered, and often combined with hot milk, that the great espresso cuisine of northern Italy developed. It is as though the ideal of espresso was somehow present from the moment northern Italians developed a taste for strong, heavy-bodied, yet filtered coffee. The rest of the technical history of espresso can be seen as a gradual achievement of that goal, a liberating of it, as it were, from the shackles of technical limitation.

In fact, it wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to argue that this taste for heavy-bodied yet filtered coffee represents a typically Italian maximization of the two cultural strains—the eastern Mediterranean (Byzantine and Arab) and the Western European—that together have made Italian culture such a continually fascinating and creative blend. The eastern Mediterranean influence is seen in the cultural premise of small cups of heavy-bodied coffee drunk sweetened and covered with froth; the Western European in the practice of filtering the coffee and often combining it with cow’s milk, and in the almost obsessive tendency to apply technological innovation to the brewing process.

ENTER TECHNOLOGY

For it is at this point, during the nineteenth century, that the cultural history of espresso also becomes a history of espresso technology. Though tinkering and gadget making has been part of coffee culture almost from its inception, the scale and thoroughness with which espresso cuisine utilizes technology remains unprecedented, and is undoubtedly one of the principal sources of its fascination for the rest of the world.

By the time the industrial revolution spread through Western Europe during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, coffee drinking was a well-established habit, and it was inevitable that the repetitive, familiar ritual of coffee brewing would provoke the interest of the tinkerers and inventors of the period.

Improving the Filter Pot

The starting point for many of these coffee-making innovations was the familiar drip or filter pot, in which the simple pull of gravity causes hot water to trickle down through a bed of coffee loosely laid over a metal or ceramic filter. There are several drawbacks to the filter-drip method. One is the slowness of the process. If the coffee is ground too finely, the brewing process may even stop altogether, and the impatient coffee lover is forced to knock the pot around or stir the grounds in an effort to speed things up. Not only is the drip method slow, but it is also relatively costly and inefficient, since the rather coarse grind demanded by the method means a less thorough extraction than could be achieved with a finer grind.

For these reasons, some of the more sophisticated efforts to apply the technologies of the early industrial revolution to coffee making expedite the drip process by either pulling the hot water through the problematical bed of ground coffee (via a partial vacuum) or by pushing it through by various expedients, including compressed air, hand-operated plungers, and the pressure of trapped steam.

Pulling and Pushing

By the 1840s the pulling approach was in use in several versions of what is now known as the vacuum brewer, in which a mild vacuum sucks the brewing water down through a bed of ground coffee.

Other coffee-maker tinkerers pursued the opposite approach. Rather than making use of a partial vacuum to pull the hot water through the bed of coffee, their devices applied pressure to the hot water to push it through. Many of these early nineteenth-century designs anticipate solutions applied later in espresso technology. In some devices a hand-operated piston forces water through the bed of coffee. In others, compressed air manually pumped into the hot water chamber provides the brewing pressure.

The method that eventually prevailed in the early espresso technology, however, utilized the trapped pressure of steam. Water brought to a boil inside a sealed chamber created steam; the confined steam then forced the water through the bed of coffee. A glance at the cutaway illustration here of a simple contemporary Moka-style coffee pot gives a general idea of how these early small steam-pressure devices worked. The first European patents for home devices using the steam-pressure principle were filed between 1818 and 1824. Various ingenious refinements to the steam pressure principle were proposed, forgotten, and proposed all over again throughout the nineteenth century, but all remained either commercially unexploited or applied only to small-scale home brewers. It was not until the early years of the twentieth century that the steam pressure principle was finally successfully applied to a large commercial machine, and the technology and culture of caffè espresso was born.

Precursors of the Espresso Machine

The first large caffè machine to utilize a variation on the steam pressure principle is credited to Édouard Loysel de Santais, who at the Paris Exposition in 1855 demonstrated a machine that used the pressure of trapped steam not to directly force the brewing water through the coffee, but rather to raise the water to a considerable height above the coffee, whence it descended through an elaborate system of tubes to the coffee bed. The weight of the hot water, not the trapped steam, applied the brewing pressure. Santais’s complex machine brewed “two thousand cups of coffee in an hour,” according to one impressed contemporary observer. It apparently brewed coffee a potful at a time, however, just as many French cafés today still brew their espresso. Despite its impressive technology, Santais’s device apparently was too complicated and difficult to operate to have any lasting influence on public coffee making.

Nevertheless, various northern Italians persisted in attempting to improve on machines like Santais’s device. Why the northern Italians continued in this effort, when it was largely dropped elsewhere in favor of other coffee-brewing methods, is a matter for speculation. It may be that the Italians, latecomers to the imperialist game and consequently without the coffee-growing colonies possessed by France and England, were forced to compensate for the high cost and relative poor quality of their coffee imports with superior brewing technology. Or it may be that for cultural reasons, perhaps related to the strong eastern Mediterranean influence, Italians simply craved a fuller-bodied cup than North Americans and other Europeans and continued to evolve technology to achieve that end.

The Bezzera Breakthrough

The next important date in the technical development of espresso is 1901, when the Milanese Luigi Bezzera patented a steam-pressure restaurant machine that distributed the coffee through one or more “water and steam groups” directly into the cup. In many respects the Bezzera machine established the basic configuration that espresso machines would maintain until the development of today’s fully automatic machines. A glance at the illustrations here reveals the familiar filter holder, the “group” into which the filter holder and filter clamp, the steam valve and wand, etc. The Bezzera design also established the emphasis on freshness and drama characteristic of the espresso system: the coffee is custom brewed by the cup for customers before their eyes. Again, this feature of espresso culture intriguingly suggests another aspect of the Turkish-style coffee culture: in traditional Middle Eastern coffeehouses the coffee is always brewed by the cup, on demand. At any rate, the concept of freshly ground coffee brewed on demand has remained a central element of the espresso system ever since Bezzera’s innovation.

The Bezzera patent was acquired by Desiderio Pavoni in 1903, who began manufacturing machines based on the Bezzera design in 1905. Pier Teresio Arduino started producing similar machines soon afterward, and other manufacturers followed. By the 1920s these towering, ornament-topped machines dominated the Italian caffè scene. Initially heat was provided by gas. In fact, it is unlikely that the large steam-pressure machines of the early twentieth century could have prevailed without the availability of gas as a steady, reliable source of heat. It was not until the 1920s and ’30s that electricity replaced gas in many machines, encouraging smaller, art moderne versions of the Bezzera design that rapidly heated relatively small quantities of water in more compact boilers.

Espresso-Powered Imagery

The 1920s also was the time in which the imagery of espresso as a symbol of urban speed and energy first emerged. The famous Victoria Arduino poster of 1922 reproduced here sums up these associations: the romantic power of steam drove both locomotive and espresso (espresso machines of the period often literally resemble sleek locomotives set on end), while the sophisticated urbanite, espresso powered as it were, rockets his way on a tazzina of coffee through the urban machine without a wasted second. Occasionally the work of the Italian Futurist movement in the midst of its celebration of urban speed and potency betrays a similar association with coffee. The famous 1910 painting by Umberto Boccioni, Riot in the Galleria, reproduced here, represents a sort of well-dressed brawl in front of a caffè. It explodes not only with the almost hysterical energy of the city, but with the powerful excitement of coffee (and presumably of the new culture of espresso) as well. Note how light shoots from the caffè like spikes of some frenzied indoor mental sun.

BREAKING THE 1½ ATMOSPHERES CEILING

Throughout the period between the wars, however, there were signs that Italian coffee innovators were not content with the 1½ atmospheres of pressure exerted on the brewing water by trapped steam alone. The pressure could be increased by intensifying the heat and thus the steam pressure, but the intensified heat often cooked or baked the ground coffee during the brewing process. It was also generally known that the boiling point was not the optimum temperature for water used in brewing coffee and that a smoother extraction of the flavor oils could be obtained by a water temperature short of boiling. Both of these concerns argued for a method of applying pressure to the brewing water other than trapped steam.

The most commercially successful of these between-the-wars attempts to increase brewing pressure involved making use of the simple power of water run from the tap. Called “electro-instantaneous” machines, these devices used electric elements to rapidly heat tap water to brewing temperature in miniature boilers, one boiler to each brewing group. Each boiler was separately connected to the tap. When the operator tripped a lever above a group, the pressure of new water introduced from the tap forced the hot water in the boiler out through the ground coffee. Depending on the strength of the local water pressure, such machines could exert considerably more than the 1½ atmospheres generated by steam pressure machines.

These devices maintained the same vertical profile as the steam pressure machines, but were smaller and reflected the art deco and art moderne design trends of the late 1920s and 1930s, with straight lines and dramatic geometries replacing the art nouveau curves of the earlier steam pressure designs.

Other efforts to beat the 1½-atmospheres ceiling involved compressed air. A charming little home machine in the possession of Milanese collector Ambrogio Fumagalli, for example, which dates from between the wars, uses a pump to apply pressure to the brewing water (for an illustration, here). And in 1938, Francesco Illy built the Illetta, a large, sophisticated commercial machine making use of compressed air.

In this painting by Umberto Boccioni (“Riot in the Galleria,” 1910) dazzling light radiates from a caffè, illuminating a frenzied city scene of the kind favored by the Italian Futurists. It is tempting to see a connection between the new culture of espresso and the nervous urban energy celebrated by the Futurists in paintings like this one.

In the same years, however, two coffee tinkerers in Milan were pursuing a direction that would have considerably more impact in espresso history. The details of their story are not entirely clear, but the ultimate outcome is: a new approach to espresso brewing that would completely transform the drink and its technology.

Spring-Powered Espresso

In the years before World War II one Signor Cremonesi patented a device that forced water through the coffee by means of a screwlike piston. When a horizontal lever was turned, it forced the piston downward in a screwing motion, pushing the brewing water, which had been injected between the piston and the filter, down through the coffee. Meanwhile Achille Gaggia, a Milanese caffè owner, was experimenting with a similar device at about the same time. The Gaggia device could be bolted onto other manufacturers’ machines, in effect replacing the old steam pressure brewing group with the new screw-down version.

World War II interrupted Cremonesi’s and Gaggia’s experiments, and during that time Cremonesi died, leaving the rights to his patent to his widow, Rosetta Scorza. It is not clear whether Scorza shared her dead husband’s ideas with Gaggia, or whether Gaggia simply proceeded on his own, but at any rate by 1947 Gaggia had taken the original idea of the piston suggested by both inventors, and transformed it into his revolutionary “lever group.” Rather than a laborious screw, the piston was now powered by a powerful spring. The operator pulled down a longish lever, which simultaneously compressed the spring and drew hot water into the chamber between the piston and the coffee. As the spring above the piston expanded, it forced the piston down, pushed the hot water through the coffee, and allowed the lever to return majestically to its original erect position. See here for a cross section of a typical spring-piston mechanism.

In 1948 Gaggia brought out the first complete machines to incorporate his new device. They were an almost instant success, and apparently were responsible for the creation of the mystique of the crema in Italian coffee culture. Note the art moderne lines and the logo on the 1948 Gaggia machine pictured here, proclaiming “Crema Caffe/Naturale” (“Natural Coffee Cream”). What constituted “unnatural” coffee cream I have no idea. Perhaps the question could only be asked by a foreigner; the emphasis is clearly on crema as a natural part of the brewing process, an evidence of richness. Historical anecdote suggests that Gaggia’s crema slogan was a way of turning a liability into an asset. According to these stories, when people asked what that peculiar scum was floating on their coffee, Gaggia and his associates called it “coffee cream,” suggesting that his new method produced coffee that was so rich that, in effect, the coffee produced its very own cream. Whatever the truth of that story, even since Gaggia’s time “crema” has become the mark of a properly brewed espresso.

The success of the Gaggia design is understandable. It finally achieved the implicit goal toward which espresso cuisine had been aspiring—the easy richness, smoothness, and full body of classic espresso. It achieved this goal by pushing the brewing water through an even more tightly packed bed of coffee than before, at a much greater pressure than ever before, assuring the rapid, complete extraction of the flavor oils characteristic of the mature espresso method.

A Performance Opportunity

What is less commonly recognized is that the Gaggia-style machines also produced one of coffee’s greatest performance opportunities. The muscular pull on the lever and its slow return to an upright position became the signature performance of the barista of the streamlined new espresso bars that replaced the more spacious (and doubtless more gracious) caffès and neighborhood bars of less hurried pre–World War II days. The boilers were smaller in the new machines, and were laid on their sides inside sleek housings, further reinforcing the updated image of speed, power, and modernity projected by the new brewing technology.

One could argue that all developments in espresso technology since Gaggia’s breakthrough are mere refinements. Certainly one can make as good an espresso with a piston-style machine as with any later machine, and owing to their simplicity, ease of maintenance, and the control they permit the skilled operator, many piston machines continue to be used. Some of the better caffès in the United States still prefer the piston machines.

Automation and Speed

Nevertheless, since the day of its introduction the effort to improve the Gaggia design has never ceased. In the 1950s the Cimbali company introduced its “Hydromatic” machine, which, like the Gaggia design, used a piston to force the brewing water through the coffee. Unlike the Gaggia design, however, the piston was powered by tap water, which was run into a chamber above and behind the piston. As more and more water entered this chamber, the piston was gradually forced down, in turn pushing the hot brewing water on the underside of the piston through the coffee. This hydraulic brewing operation was controlled “automatically” by a button, hence the name “Hydromatic.” The Cimbali Hydromatic is illustrated here. Like the Gaggia design, the hydraulic machine is a technological classic that is valued for its sturdy simplicity, and designs almost identical to the original Cimbali machine are still being manufactured and sold.

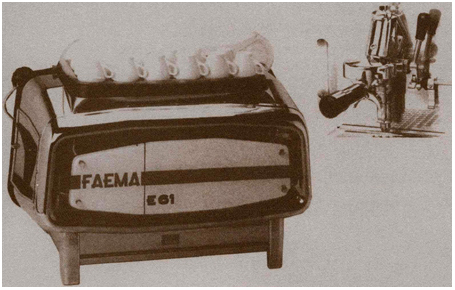

The Cimbali machines were quickly upstaged by the introduction in 1960 of the famous E61 machine of Ernesto Valente’s FAEMA company, the first espresso device to use an electric pump to force the hot water through the coffee. The E61 also incorporated several other recently developed innovations, the most important of which was a method of heating brewing water in small batches by means of a device called a heat exchanger. Recall that the Gaggia-style machines heated the water used for both brewing and steam production in a large tank or boiler at the heart of the machine, a feature that presented two disadvantages: the machine was slow to heat to operating temperature, and the water sometimes became saline or stale when held in the tank for long periods. The heat exchanger is a tube that carries fresh water through the tank of already hot, “old” water. As the electric pump pushes fresh water through this tube, it is heated by the surrounding water of the tank, yet is protected by the tube from contamination. Thus it is delivered hot but fresh to the brewing head. Meanwhile, the hot water in the tank is used only for producing steam for milk frothing.

Another of the technical elements that made the Valente design successful was the use of a decalcification process to soften the water before it entered the pump and heating apparatus, thus preventing the mechanism from being fouled by lime deposits. Finally, the Valente design circulated hot water from the tank through concealed cavities in the group or brew head, thus making it unnecessary for the operator to preheat the group by running brewing water through it, as was required by the Gaggia design. The illustration here indicates the main interior components of the Valente design and its many successors down to the present.

Externally, the Valente FAEMA design replaced the long lever of the Gaggia design with a much smaller lever. The operator, rather than pulling on a long handle, simply activates the pump by tripping the lever, and after a suitable amount of coffee has been pressed into the cup, trips the lever a second time to end the brewing operation.

Like both the Gaggia manual piston and Cimbali hydraulic designs, the FAEMA machine has been an enduring classic. Some of the original machines are still operating, and new machines using virtually the same design continue to be manufactured and sold, though by firms other than FAEMA.

INFORMATION AGE ESPRESSO

The principal developments since the E61 have been in the direction of automation, and as industrial age modulated to information age, the computer and its potential for controlling complex, repeated operations entered the picture. The most prevalent style of machine in Italy and the United States today is usually described as a semi-automatic machine, which simply means it is a refined, push-button version of the Valenti E61. A pump still pushes the instantly heated hot water through the coffee, though the pump and heating operation is usually activated by a button rather than a lever. Many semi-automatic machines incorporate a computer chip and control panel, which regulate the flow of water through the coffee to produce anywhere from a single corto or short espresso to a double lungo or long espresso. Thus the operator is relieved by the computer of the need to cut off the flow of water through the coffee at the correct moment. For an illustrated description of a typical semi-automatic machine, here.

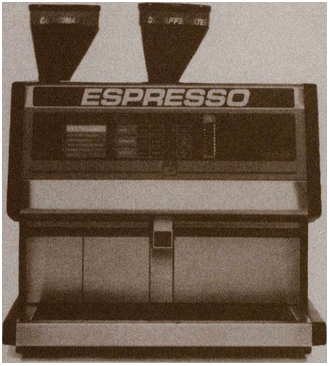

In the semi-automatic machine, however, the operator still loads the filter with coffee, disposes of the grounds, froths the milk, and assembles the final drink. Beginning in the 1980s, fully automatic machines have appeared, which grind, dose, and tamp the ground coffee, brew it according to the directions punched into the machine by the operator, and dispose of the grounds. With the popularity of decaffeinated coffee, particularly in Switzerland, Germany, and North America, many of the larger automatic machines incorporate two separate grinders, and will produce either decaffeinated or regular espresso, in any increment of quantity, at the touch of a button. Most of these fully automatic machines do not heat and froth the milk and assemble the final drink, however, which is still left to the barista.

Machines That Do It All

Inevitably, machines have been developed that do it all, including frothing the milk and assembling the drinks. Some are modest box-shaped devices that sit atop counters in European offices, and others are muscular coin-operated devices that wait dutifully in airports and waiting rooms. Although these European vending and office machines brew genuine espresso, their milk-frothing function tends to be compromised by various technical expedients.

This was not true with the made-in-USA Acorto 990, the first fully automatic machine to take into account the North American taste for mammoth caffè lattes and other oversized frothed-milk-and-espresso drinks. The Acorto 990 (for an illustrated description, here) and its progeny use fresh, cold milk, and brew the espresso, froth the milk, and assemble the drink in automatic but authentic fashion. Kept in proper running order, the Acorto machines produce espresso cuisine virtually indistinguishable from the production of a good barista working a semi-automatic machine in classic fashion.

However, so far most Italian and North American caffès and bars have stuck with the simpler manual and semi-automatic devices, at most trusting the machine to measure the water and time the brewing but leaving the loading, tamping, frothing, and assembling procedures to the operator. Italian bar operators argue that fully automatic machines cannot be trusted to administer the process with the same precision as a well-trained operator, and many also prefer to avoid the higher maintenance costs attributed to fully automatic machines. Finally, there is the psychological importance of ritual in both Italy and North America. In both cultures, espresso means an experience as well as a beverage, and in Italy, in particular, that experience involves a skillful barista who performs the ritual of espresso with panache, and who can produce customized espresso, with each demitasse perfectly tuned to the individual customer’s preferences.

Invisible, Unseen Power

The visual appearance of the fully automatic machines tends to reflect the reticence and gestural understatement of the computer age. Rather than flaunting theatrical ornaments atop an elegant metal tower like the twenties Bezzera/Pavoni machines, or promoting a macho pull on a long phallic handle like the 1950s Gaggia design, the machines of the 1990s present a sleek, understated cabinet and involve minimal theatrics from the operator. The vision of modernity they seem to aspire to is the invisible, unseen power of the computer, rather than the extraverted power of industry suggested by the earlier designs.

Of course we continue to experience the contradictions of the high-tech, high-touch paradox pointed out by Alvin Toffler in his 1970 book, Future Shock. At the same historical moment that the espresso machines of the present express the understated, reticent power of the computer, other perfectly ordinary machines come tarted up with copper siding and various irrelevant pipes and gewgaws meant to suggest (to impressionable diners) the belle époque, while still others are honest replicas of the famous machines of the recent past, like the FAEMA E61 noted earlier. Thus at the same moment that we reach toward ever greater automation and efficiency, we simultaneously clutch nostalgically at the forms and rituals of the past.

DOMESTIC ESPRESSO

From the introduction of the Bezzera/Pavoni machines at the turn of the century to the present, espresso cuisine has been a largely public phenomenon. Small home devices have usually mimicked the larger machines.

The exception may be the small, steam pressure coffee makers of modest ambition the Italians simply call caffettiera, or coffee pots. From the mid-nineteenth century until the present the design of these devices has changed very little. A look at the historical examples here and the contemporary examples here together give some idea of the range and persistence of these little devices.

All work on the simple principle of the earliest caffè machines: water is set to boiling by stove, alcohol lamp, or electric element; when steam pressure builds sufficiently inside the water chamber it forces the water through the coffee. There is no steam valve for frothing milk; seldom is there even a means to cut off the flow of coffee. To avoid running too much water through the coffee and ruining it through overextraction, one must resort to expedients—carefully limiting the amount of water put in the reservoir, for example.

Bringing the Bar Home

But parallel to the uneventful history of these eternal little devices has been a steady development of more complex (and more expensive) machines that, as one Italian advertisement puts it, “bring the bar home.” And since the machines at the bar have changed over the years, so have the home machines that imitate them.

Examples of these machines are described and illustrated here. Note that most of the developments in the full-sized caffè machines are mirrored here, from the little Gaggia machine with a spring-loaded piston to the Saeco full automatic. The range of aesthetics of the large machines is mirrored as well, from the extraverted steam-engine look of the Europiccola to the no-nonsense reticence of the Saeco Super Automatica Twin.

For those considering purchasing a home machine, I give some advice here. Detailed suggestions on using these devices is provided in Chapter 9.

ESPRESSO BREAK

THE CAFFÈ GIANTS

In Italy the great espresso machines of the past evoke the same rush of admiration and nostalgia that certain old automobiles and jukeboxes do in the United States. The six machines that follow represent key developments and trends in the history of the caffè espresso machine.

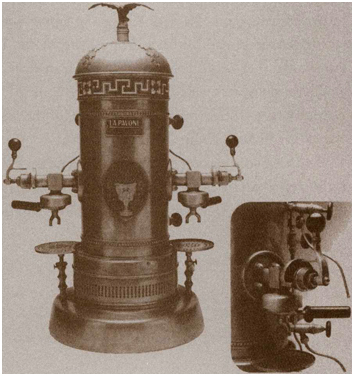

La Pavoni espresso machine

1920S AND 1930S

La Pavoni. A machine typical of those manufactured in the 1920s by Pavoni and many other firms. Machines like this one essentially created espresso culture and carried it across Europe and the Americas. Steam pressure is generated in the giant gas-fired boiler (see the cross-section illustration here), which forces hot water through the coffee, held in a filter holder almost identical to those used in machines today. Note, for example, the familiar shape of the group, the filter holder, and the steam wand. Only the lever operating the coffee valve, reminiscent of a steam engine throttle, differs from the various levers and buttons that control coffee output in later machines.

Although these machines forced water through the coffee at a paltry 1½ atmospheres, compared to the 9 or more atmospheres considered ideal today, they introduced several innovations that carried the day for espresso: a richer coffee, brewed under pressure; a fresher coffee, custom brewed by the cup; and milk heated by having steam run through it, eliminating the flat taste acquired by milk heated in the conventional manner. The beauty and drama of these machines, rising above caffè-goers like gleaming towers and surrounded by wisps of steam and elegant ministrations of baristas, undoubtedly further contributed to their success.

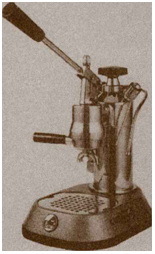

Early Gaggia spring-piston machine

1940S AND 1950S

Early Gaggia Spring Piston Machine. Soon after World War II, Achille Gaggia produced the first machine to successfully press hot water through the bed of finely granulated coffee at six to nine times the pressure generated by trapped steam alone. Gaggia’s machine used a piston powered by a spring. The spring was compressed by a lever; the barista pulled down the lever, and as the spring-driven piston pressed the water through the coffee the lever returned majestically to its upright position. See the cross-section illustration here.

The slogan on the machine reads “Crema Caffè/ Naturale” (“Natural Coffee Cream”). This slogan refers not to the addition of actual cream to the coffee, but rather to the dense golden froth, or crema, “naturally” covering the surface of the espresso, a sign of richness and a symptom of the greater brewing pressure achieved by the new Gaggia design.

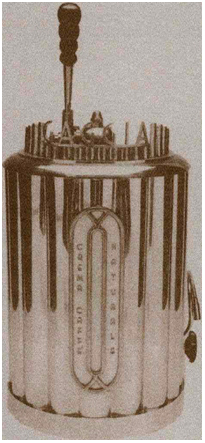

Cimbali hydraulic machine

1950S AND EARLY 1960S

Cimbali Hydraulic Machine. In 1956 the Cimbali company introduced the world’s first hydraulically powered piston espresso machine. The piston was powered by the simple force of tap water; see the illustration here. The earliest hydraulic machines, like the one on this page, were complex and extraverted in their exterior design, and required the operator to closely control the various phases of the brewing cycle. Later versions were almost completely automatic, requiring only the pressing of a switch to initiate the brewing operation.

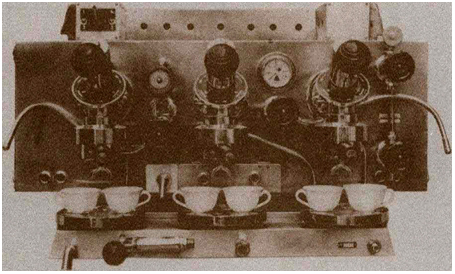

FAEMA E61 machine

1960S AND 1970S

The FAEMA E61. The momentous decade of the 1960s was heralded in the espresso world by the introduction of the FAEMA E61, a machine lavish with innovation. The brewing water was heated on demand, rather than held hot in a large tank or boiler; a pump rather than a spring-driven piston supplied the brewing pressure; a decalcification system prevented the pump and heating mechanism from becoming fouled by hard water deposits; and hot water from the boiler, circulating through the group, maintained an even operating temperature in its metal components. Despite the advanced, automated nature of the machine’s operation, the group, pictured in the detail illustration, retained some of the complex, romantic look of the brewing apparatus on earlier machines. Brewing was controlled by the little lever to the right of the filter holder.

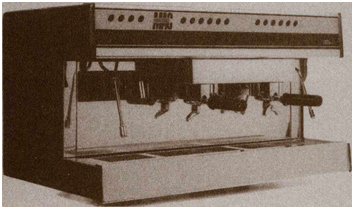

Typical semi-automatic machine: Nuova Simonelli MAC Digit

1980S AND 1990S

Semi-Automatic and Automatic Machines. The machine on the right is typical of many evolved in the 1980s by numerous manufacturers. The operator still must dose and tamp the coffee, but the brewing process itself is controlled by microchip and button. Note the line of six buttons above each group. In the case of this machine the operator can, from left to right, select a single short serving, a double short serving, a single regular serving, two regular servings, initiate a continuous flow of water through the coffee, or stop the operation entirely. Other machines may present considerably more complex control panels and options.

Acorto 990 machine

The U.S.A.-made Acorto 990, illustrated on the right, is a fully automatic machine designed with the North American cuisine in mind. Several European manufacturers also produce fully automatic machines, but most of the European automatics still leave the milk frothing to the barista. The Acorto will produce up to twenty-two different espresso drinks, ranging from short espressos to mammoth caffè lattes, in either regular or decaffeinated versions. Note the twin bean silos, one for regular and one for decaffeinated beans. The machine also incorporates refrigeration for the milk.

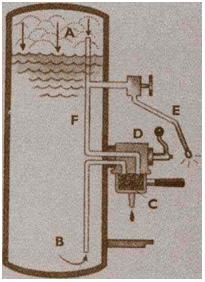

NINETY YEARS OF ESPRESSO TECHNOLOGY

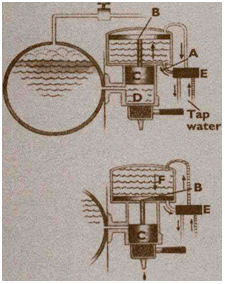

On the left is a cross section of a typical steam pressure machine of the kind popularized by Pavoni and Victoria Arduino in the early part of the twentieth century and described here. The pressure of steam trapped in the gas-fired central boiler (A) presses downward on the hot brewing water (B), forcing it through the compressed bed of coffee (C) when the operator opens a tap (D). The upper part of the boiler is tapped to provide steam for frothed milk drinks through the familiar steam wand (E). Not indicated is the option of directing steam through the spent coffee grounds, so as to dry them into tidy cake that pops out of the filter without clumsy digging or rinsing. This step was not incorporated in later machine designs because the stronger brewing pressure generated by more advanced machines tended to compress and dry the spent grounds automatically.

Steam-pressure machine

The famous Gaggia manual spring-piston machine (here) was introduced soon after World War II. The drawing on the left shows a cross section of a brewing group in such a machine. When the operator depresses the lever (A), a spring (B) is compressed above the piston (C), drawing hot water into the cylinder (D) below the piston. The spring then forces the piston back down, pressing the hot water through the bed of ground coffee. The hot water is drawn from a tank similar to the boiler in the Pavoni steam pressure machine, although in most manual piston machines the boiler is laid on its side inside a streamlined housing. As with the Pavoni design, the boiler also provides steam for milk frothing.

Manual spring-piston machine

The first hydraulic espresso machine was introduced by the Cimbali company in 1956. Like the Gaggia-style spring-piston machines, the hydraulic machines use a piston to force the hot water through the coffee bed. However, in the Cimbali and later hydraulic designs the piston is powered by tap water, and the long lever replaced by a switch. See the illustration on the right, a cross-section detail of a typical hydraulic brewing group. The diagram appears complex at first glance, but represents a simple operating principle: tap water introduced alternately above and below the large piston forces it up and down. The large piston drags the smaller piston below with it, and the smaller piston forces the hot water through the coffee.

Hydraulic machine

When the operator activates the switch beginning the brew cycle, the valve at (E) allows tap water (not hot water from the tank) to enter the larger cylinder at (A), forcing the larger piston (B) upward. The larger piston lifts the smaller piston (C), allowing hot water from the tank to enter the small cylinder at (D). When the appropriate volume of brewing water has flowed into the small cylinder, a mechanical trigger is tripped, directing the valve at (E) to route tap water into the larger cylinder above the piston at (F). This new influx of water forces the large piston down, pushing the tap water below the piston out, and forcing the hot water in the smaller cylinder down through the coffee. The Cimbali hydraulic design, like the Gaggia spring-loaded manual, has proven to be a classic, and machines utilizing the principle continue to be manufactured.

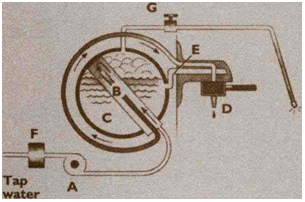

Electric pump machine

However, the future, or at least a large part of it, belonged to the electric pump design introduced in 1960 by the FAEMA company. The basic configuration of the FAEMA E61 is still used in the majority of caffè espresso machines manufactured in the world today. A cross section typical of such machines is represented on the preceding page. Here an electric rotary pump (A) rather than piston provides the brewing pressure. The pump forces cold water into a heat exchanger (B), a largish tube that is surrounded by the hot water of the familiar boiler (C). The cold water inside the exchanger is heated by the surrounding hot water, but is untouched by it, and is forced by continued pressure from the pump into the brewing group (D) and through the coffee. Steam for frothing continues to be supplied by the boiler. A line from the boiler (E) also maintains uniform heat in the brewing group with a convection current of hot water, and a water softening unit (F) keeps the pump and lines from becoming fouled with mineral deposits. Steam for milk frothing is supplied in the usual way by tapping the top of the boiler (G).

In pump machines manufactured today electronic instrumentation often controls the volume and temperature of the brewing water. Some machines may substitute a second boiler in place of the heat exchanger so as to maintain greater control over brewing temperature. Fully automatic machines grind, load, and tamp the coffee for brewing. And the Acorto 990 described here even froths the milk and combines it with the coffee before dispensing the finished drink. Nevertheless, all of these sophisticated machines are built around the fundamental electric pump technology introduced in 1960 by the FAEMA E61.

ESPRESSO BREAK

A CENTURY OF HOME ESPRESSO BREWERS

AT HOME IN ITALY: EARLY STEAM PRESSURE BREWERS

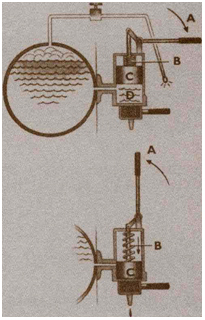

Italian Steam Pressure Brewer (illustrated here). A design typical of many small tabletop brewing devices manufactured in northern Italy throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An alcohol lamp heated water in a sealed reservoir at the lower part of the device. The pressure of steam trapped in the reservoir gradually forced the water up a tube and through a bed of coffee. The brewed coffee exited from the top of the pot via the curved tube into a cup placed next to the machine.

Steam Pressure Brewer with Separate Coffee Chamber (illustrated here). In the later nineteenth century steam pressure designs appeared that separated the filter containing the coffee from the water-steam reservoir to avoid baking the ground coffee. Most of these devices presented a profile similar to this early twentieth-century design from the collection of Ambrogio Fumagalli. The water-steam reservoir is at the right. The trapped steam pressure in the reservoir forced the water up and along the horizontal tube at the top of the device, then down through the coffee held in the filter chamber on the left.

This example incorporates an additional useful feature: a valve controlling the flow of hot water from the reservoir to the filter holding the coffee, which permitted the user to stop the brewing process at will. In the illustration, the control valve appears as a small lever at the top of the reservoir.

CRANKING UP THE BREWING PRESSURE AT HOME

Compressed Air Pressure Brewer (illustrated here). In this unusual device from the 1920s, the pressure of compressed air forced the brewing water through the ground coffee. Hot water was placed in the elevated central reservoir. The water was then forced through the ground coffee by means of air pumped into the top of the reservoir by the small hand pump protruding from the base on the left. A concealed tube conducted the air to the top of the reservoir. The ground coffee was held near the bottom of the reservoir in a metal filter.

Italian steam-pressure brewer

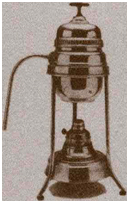

Gaggia Spring-Loaded Piston Brewer (illustrated here). Doubtless an effort by Gaggia to extend the popularity of its revolutionary new lever-operated commercial machines (see here) to the home market, this machine from the 1950s used a spring-loaded piston to force hot water through the tightly packed coffee, producing a near caffè-quality espresso. When the handles on either side of the device were clamped down, a spring was compressed inside the top of the central tower. The spring then forced a piston down through a reservoir filled with electrically heated water, pressing the water through the coffee, which was held in a commercial-style filter and filter holder at the bottom of the device. (Also from the collection of Ambrogio Fumagalli.)

Steam-pressure brewer with separate coffee chamber

Pavoni Europiccola. A charming device still being manufactured, the Europiccola combines the belle époque look of the early Pavoni bar machines with a manually operated lever reminiscent of the Gaggia machines of the 1950s. The lever does not compress a spring, however, as in the Gaggia-style machines, but directly acts on the piston. In other words, the operator simply leans on the lever and presses the water through the coffee.

Compressed air pressure brewer

Gaggia spring-loaded piston brewer

Pavoni Europiccola brewer

STEAM PRESSURE BREWERS: 1950S TO THE PRESENT

“Atomic” Steam Pressure Brewer (illustrated here). Both the name “Atomic” and the shape—simultaneously reminiscent of a mushroom cloud and an overstuffed sofa—mark this device as a product of the 1950s, although similar designs had been produced earlier in the century by the same manufacturer. A stovetop machine, the Atomic used the pressure of trapped steam to force the hot water through a detachable, commercial-style filter and filter holder. The addition of a steam valve and wand for making drinks with frothed milk is unusual; most small European home espresso brewers did not, and still do not, incorporate this feature, since most Italians prefer their espresso without milk.

“Atomic” steam-pressure brewer

The addition of the steam valve made this device a strong seller in the United States and Australia in the 1960s, when espresso drinks with milk were first becoming popular in both countries. My first two home espresso brewers were Atomics, and I still feel a pang of nostalgia when I see one. The manufacturer of the Atomic is now out of business. It was a rather cranky design that required an attentive operator and some crafty improvisation to produce decent espresso. The small electric countertop devices popular today are easier to use.

The illustrated example comes from the collection of the Thomas Cara family, San Francisco. Thomas Cara, a pioneering West Coast importer and distributor of espresso apparatus, customized many of the Atomic brewers he sold by adding the little steam pressure gauge seen here protruding from the top of the machine.

Braun Espresso Master. Little electric countertop machines like this one from Braun, and similar models from Krups and other manufacturers, are changing the way North Americans make their coffee. Used carefully, these relatively inexpensive devices can make decent espresso drinks with frothed milk and weak but passable straight espresso. They use the pressure of trapped steam to force the water through the coffee, just as does the Atomic machine above and the earlier devices illustrated here, but they employ an electric element to heat the water and incorporate a steam wand for frothing milk and a valve for stopping the flow of coffee at the optimum moment to avoid overextraction. Machines like this one are a good place to start for caffè latte lovers who want to do it at home. Like many of these small machines, the Braun Espresso Master incorporates a gadget on the end of the steam wand designed to help the neophyte successfully froth milk.

Braun Espresso Master

HOME PUMP MACHINES OF THE 1980S AND 1990S

Baby Gaggia (illustrated here). This Gaggia machine from about 1980 typifies the first wave of small home pump machines to reach the North American market. It was enormously successful, particularly in Italy, where few urban newlyweds found themselves without a Baby Gaggia after the wedding presents had been opened. Sturdy and authoritative with its clean lines and cast-metal case, it attempted to bring into the home the capabilities of the semi-automatic pump machines that had come to dominate the caffè scene in the 1970s and ’80s.

Most of today’s home pump machines tend to be smaller, lighter in weight, and cheaper, but they work in the same way. Water is held in a removable, refillable reservoir, and flows as needed into a small boiler, where it is heated to brewing temperature and forced by means of a vibrating electric pump through the ground coffee held in a caffè-style filter and filter holder. Steam for milk frothing is produced by the same boiler, but only after a transitional procedure in which the temperature in the boiler is raised sufficiently to produce a sturdy flow of steam. See here for a cross section of a typical home pump machine.

Baby Gaggia home espresso machine

Saeco Super Automatica Twin. The Saeco Super Automatica Twin and its somewhat smaller relative, the Rio Automatica, were the first fully automatic home machines to be marketed in the United States. Both operated much like the Baby Gaggia described above, but they also ground the coffee, loaded it, tamped it, and after the brewing operation disposed of the grounds, all at the touch of various buttons. Saeco automatic home machines that look and work about the same as the Super Automatica continue to be sold in the United States under different model names.

Saeco Super Automatica Twin