10 CARTS, CAFFÈS, AND HOUSES

ESPRESSO PLACES

Some years ago I was sitting in downtown Seattle over an empty cappuccino cup near one of Seattle’s ubiquitous espresso carts. This particular cart was nestled under the marquee of the Coliseum Theater, a landmark movie palace from the early days of cinema then closed and waiting for someone with money to turn it into boutiques. The cart was owned by Chuck Beek, one of the entrepreneurs credited with starting Seattle’s historic espresso cart business.

I assume most readers now are familiar with espresso carts: espresso bars on wheels, complete with machine, grinder, small refrigerator, and the rest of the gear needed to produce espresso cuisine, all neatly built into a cart compact enough for one or two people to roll out of seclusion every morning into some promising urban setting filled with passing potential espresso buyers. An innovator named Craig Donarum built Seattle’s first espresso cart in 1980, sold that cart to Chuck Beek some months later, and from that one cart hundreds more have sprung, to the point that hardly a large filling station or supermarket in the Seattle area doesn’t have an espresso cart or stand in front of it, dispensing Italian coffees to passing shoppers and motorists.

Chuck’s newest cart under the Coliseum Theater marquee was surrounded by a few tables and chairs, some T-shirts and postcards, and a neon sign, which read simply CAFFEINE. On that morning there were three or four people lined up at the cart buying caffè lattes to take back to work, some of them exchanging neighborhood and workplace gossip with Chuck. The tables were occupied by people doing the time-honored things people do while drinking coffee: one man was reading a newspaper, several well-dressed women were holding an animated conversation (I later learned they worked at the nearby Nordstrom department store), and I was sitting as I have for so many hours of my life, looking at the world from over my recently emptied cappuccino cup and thinking.

FROM CAIRO TO COFFEE CART

My thoughts on that morning had taken off from espresso carts and landed, after some detours, several centuries back at coffee’s first breakout into the streets, when entrepreneurs took coffee beyond the confines of Muslim Sufi meetings in early sixteenth-century Cairo and created history’s first ad hoc coffeehouses. These informal, open-air establishments were probably more coffee stands or kiosks than houses, and must in many ways have resembled Chuck Beek’s cart in Seattle. The illustrations that accompany nineteenth-century European travelers’ accounts give the impression, for example, that the less formal coffeehouses of Muslim tradition were simple, open-air pavilions or kiosks that, like Chuck Beek’s operation, simply slipped into unused urban spaces and allowed their seating arrangements to spill casually out into the streets. The customers sitting at the tables in these illustrations look to be occupying themselves in much the same way as those of us sitting under the Coliseum Theater marquee in 1992: some quietly talking, others alone, lost in thought, observing the passing scene, or reading, but all representing aspects of the peculiar sort of semi-intellectual loafing—reading, talking, writing, playing chess, staring into space, and thinking—typical of coffeehouses, cafés, and caffès throughout history.

Resistance to Improvised Institutions

It is even possible to see a parallel between the resistance these early coffeehouses suffered from religious and secular authorities and the (albeit much milder) resistance the Seattle espresso carts faced fifteen or twenty years ago, when they were hounded by municipal authorities for lacking proper equipment and permits. In both cases rather humble urban entrepreneurs and their coffee-drinking clientele managed in the end to triumph over the resistance of authorities to the irregularities presented by such improvised institutions. And in both cases we can sense the liveliness and humanity such operations bring to the urban scene, the way the simple presence of a cart selling coffee and a few tables and chairs can transform a corner that (in the case of Chuck Beek’s operation) otherwise would have been deserted, inhabited only by scraps of newspaper and weeds poking out of the sidewalk. An espresso machine and a few tables and chairs instantly create a place where you can be rather than simply pass through.

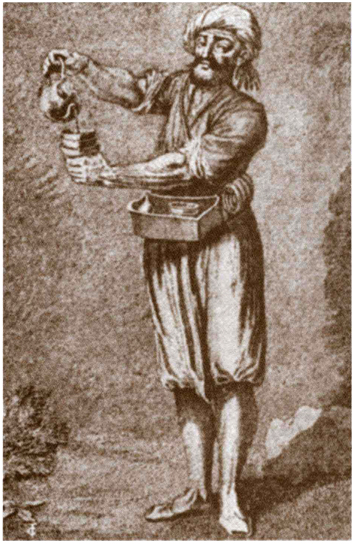

There is an even more humble archetype of public coffee selling that has an equally long history: the coffee vendor, the lone man (or woman) with a pot of coffee, a few cups, and a stool, who wanders the streets and sets up wherever somebody slows down long enough to drink a cup of coffee. References to such entrepreneurs abound in the published history of coffee. An eighteenth-century illustration of a Near Eastern coffee vendor is reproduced here. I hardly expected to encounter similar shoestring entrepreneurs in the 1990s, but given the popularity of espresso drinks, I should have known better. While waiting in a cab in a toll line in Boston a few years ago, I saw a robust young man striding between the stopped cars, a sort of insulated tank on his back, a cup dispenser on his belt, and a sign advertising CAFFÈ LATTE on his chest, serving hot coffee and consolation through car windows to frustrated motorists.

Design vs. Serendipity

The capacity for a modest, self-contained espresso-selling operation to transform a dead space that people simply walk through on their way to somewhere else into a lively arena for human interaction and contemplation has, of course, not gone unnoticed by planners, architects, and building owners. Just across the street from Chuck Beek’s espresso cart was a Starbucks espresso kiosk, situated in the glossy lobby of the City Centre building.

Although the Starbucks organization started as a small coffee chain and continues to exhibit an impressive passion for quality, it nevertheless is an operation for the most part antithetical to Chuck Beek’s: enormous in scale, sleek if not slick in its handling of marketing, graphics, and architecture, partnered with a quantity of other corporate gorillas, and traded on stock exchanges. That contrast in style and scale was displayed here: the Starbucks kiosk was splendidly designed and exquisitely situated among indoor plants and marble, the result of careful design rather than casual serendipity like Chuck’s location across the street. Nevertheless, the continuity with the first coffeehouses and kiosks in sixteenth-century Cairo continues to be striking: again a public space, in this case impressive but impersonal, filled with benches that only an architect could love, is transformed into a space where people, at least briefly, talk, read, and contemplate over coffee. Even the open, pavilionlike design of the Starbucks installation suggests the continuity with the very beginnings of the public celebration of coffee.

Throughout its history coffee has been sold by strolling street vendors, who in effect bring the coffeehouse to the customer. This vendor, as depicted in an early eighteenth-century French travel book, looks obviously undercapitalized but is nevertheless elegant in gesture and clearly confident of his product.

A PECULIAR STYLE OF MENTAL RECREATION

It remains an open question whether the particular brand of intellectual loafing associated with the coffeehouse from its inception: reading, talking, chess playing, and staring into space and thinking, is directly related to the special kind of mental intoxication peculiar to coffee and caffeine (I believe that it is), or whether the character of the coffeehouse, once established, simply maintained itself for other cultural reasons. What is certain is that as coffee spread through the world so did the coffeehouse and its peculiar style of mental recreation. From Cairo it was carried to Syria, from Syria to Turkish Constantinople, from Turkey to Venice via trade, and to Vienna via the failed Turkish siege of that city in 1683. From Venice and Vienna the habit of coffee and coffeehouses spread to the rest of Western Europe, and from there to North America.

ESPRESSO REDEFINES THE AMERICAN COFFEE PLACE

The first American coffeehouses were modeled on those in England, but appear to have been more taverns and inns than coffeehouses in either the Muslim or the modern sense. How these early tavern-coffeehouses evolved into the array of coffee-drinking establishments familiar to North Americans of the 1950s (the coffee shop of vinyl booths and bottomless cup, the diner, the roadside café and truck stop) is not clear. But what is clear is that espresso, arriving from Italy in the 1930s through 1950s, has redefined the North American coffeehouse and café.

Espresso from its inception was a public phenomenon, the application of technology to coffee making on a scale difficult to duplicate at home, at least until recently. It permitted the production of a coffee so technically superior to the simpler coffees Italians brewed at home that it added a technical reason to the social reasons for taking coffee in public. Not only was it more fun to drink coffee in a bar of caffè, but with the advent of espresso the coffee tasted better than coffee brewed at home, and embodied a mystique or glamour as well.

From Club to Caffè

Espresso appears to have been introduced into American life by Italian immigrants, who established informal social clubs, places where men from the Italian-American community met to drink coffee from the recently popularized espresso machines, play cards, talk, and cut business deals. The transformation of these social clubs into public caffès, where the Italians were joined and often displaced by the writers, artists, and intellectuals who found a sympathetic atmosphere in Italian-American neighborhoods, was a gradual development, and one that in some places still continues.

Coffeehouses along a river in Damascus, as depicted in an early nineteenth-century engraving. The informality of the arrangements in these places mirrors a similar informality in today’s impromptu street cafés created by espresso carts and stands.

One of the most fashionable places to take a cappuccino in San Francisco during the late 1980s, for example, was a small, plain Italian cigar-store-cum-caffè, which, like so many similar places before it, was in the process of changing from neighborhood hangout for local Italians to destination for in-the-know artists, writers, and professionals. On the other, earlier end of the chronology, the first American espresso caffè for which I have a date is Caffè Reggio in New York’s Greenwich Village. The Caffè Reggio was founded as a social club in 1927, but by the 1950s had been pretty much converted to an artists’ and writers’ hangout. It is still in business, by the way. The original espresso machine has been retired to icon status in one corner, but the 1930s Little Italy, garage-sale baroque furniture and bric-a-brac interior continues splendidly intact.

Espresso Goes to College

By the 1950s Italian-Americans were opening caffès that, from their inception, catered to a mix of patrons, including both Italian-Americans and a local mélange of writers, artists, and similar types. Many of these postwar establishments were situated in university communities, like the Caffè Mediterraneum in Berkeley (opened in 1958). I clearly recall the mid-1960s crowd in the Mediterraneum, which typically combined students; a few faculty; some older intellectuals whose main function in life seemed to be sitting at the same table every day and pontificating to one another; various brands of radicals, from early Black Power advocates to orthodox Marxists to sentimental Trotskyists; and a table of Italian locals from the neighborhood, including the mailman and the barber from next door.

Today college communities continue to support a growing espresso caffè culture, as American students discover what their French counterparts have known for centuries: that studying at a marble-top table over a cappuccino (or café crème beats the library every time. The commitment of student communities to espresso often can be fierce and rather exclusive. A friend reports walking into a large caffè opposite the University of California at Berkeley and asking for coffee. “We don’t serve coffee,” growled the barman in response. “We only serve espresso.”

MUSIC AND SUBVERSION

Patrons at early Middle Eastern coffeehouses didn’t restrict themselves to reading, talking, and contemplating. They also listened to music, watched puppet shows, and listened to storytellers and other performers. “Generally in the coffeehouses there are many violins, flute players, and musicians, who are hired by the proprietor of the coffeehouse to play and sing much of the day, with the end of drawing in customers,” wrote Jean de Thevenot in his seventeenth-century account of Turkish coffeehouses.

There was also considerable concern among political authorities regarding the nature of the talk that went on at sixteenth- and seventeenth-century coffeehouses, both in the Near East and in Europe. With so many people spending so many hours comparing notes on the events of the day, might not the conclusions they reached be dangerous to the current political and social order? This fear more than any other probably lay behind the numerous early efforts to suppress coffeehouses. Charles II of England, for example, in his very short-lived (eleven day!) suppression of coffeehouses in 1675, contended that “in such houses … divers false, malitious and scandalous reports are devised and spread abroad to the Defamation of His Majestie’s Government, and to the Disturbance of the Peace and Quiet of the Realm.”

Monarchical Misgivings

Events in the eighteenth century seemed to confirm such monarchical misgivings. Coffee and coffeehouses are credited with roles in both the French and American revolutions, as well as in the Enlightenment, the period in Western thought that planted the seeds of those revolutions. The famous Parisian Café Procope was the regular haunt of Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire and Condorcet, and Camille Desmoulins’ speech at the Café Foy is said to have set off the first overtly rebellious act of the French Revolution, the storming of the Bastille. Across the Atlantic, Boston’s famous coffeehouse, the Green Dragon, was called, in an often-cited description by Daniel Webster, “the headquarters of the Revolution.”

ANOTHER ARCHETYPE

Such potentially subversive carrying on, combined with the long-established coffeehouse custom of offering small-scale, informal entertainment, connects most clearly with still another North American archetype of the public dispensing of espresso, the counterculture coffeehouse, the candle-in-a-bottle, poster-on-the-wall, informal nightclub of the rebels, poets, Beats, and folk and jazz lovers of the 1950s. Such places, which in the 1950s often appeared in the same neighborhoods as the Italian-American social clubs turned espresso caffès noted earlier, were usually opened by artist-musician-writer types to cater to the same, and put less emphasis on espresso, reading, and contemplation than their Italian-American counterparts, and a bit more on music, performance, wine, and beer.

The counterculture coffeehouse appeared on its way out during the sleek 1980s, but it has now made a robust comeback in urban pockets all over the country, from Los Angeles to Seattle, where if I had risen from my table under the Coliseum Theater marquee that day in the early 1990s and walked south a few blocks, I could have taken an excellent espresso at a dozen classic coffeehouses, where by day a sleepy restfulness prevails, while you feel the casual artist funk of the decor waiting for nightfall and the arrival of the first musicians and performers.

Intimacy and Experiment

Coffeehouses provided and still provide a range of cultural possibility that is virtually unique in our society: they function as the usual coffee-culture hangouts for reading, talking, and contemplation; as art galleries free of the taste-making controls of commercial galleries; as informal nightclubs free of the taste-making controls of the commercial music industry; and as places where artists and performers as diverse as poets, stand-up comedians, magicians, political satirists, and belly dancers can entertain their own small but passionate audiences, nurturing an aesthetic culture based on face-to-face intimacy and experiment rather than passive consumption of media and spectacle.

It is difficult to determine how important espresso in particular, and coffee generally, are to the gestalt of the counterculture coffeehouse, since beer and wine are usually also consumed there. But the historical association of coffeehouses with a sort of alternative aesthetic culture suggests that the particular mental intoxication of caffeine and coffee, a sort of individualistic mental reverie, promotes a different kind of cultural stance, and a different kind of art, than the more diffused, often soggier and more collective euphoria of alcohol. If so, coffee and the espresso machine are central to the maverick contribution that the American coffeehouse has made and continues to make to North American aesthetic culture.

London youths stimulate themselves at one of the some 2,000 espresso bars that dotted Great Britain during the British espresso bar craze of the post-World-War-II period. No doubt a Vespa or Lambretta waited just outside the door. By the 1970s it was hard to find an espresso in Great Britain, though a revival is now underway.

THE SPECIALTY COFFEE CONTRIBUTION

The last strand of recent coffee history to contribute to contemporary espresso culture is what is often called specialty coffee, a phenomenon that, like the Italian-American caffè and the counterculture coffeehouse, was born (or reborn) in the 1950s and has been gaining momentum ever since. The specialty coffee store is, of course, the place where you buy, usually in bulk, coffees with names like Ethiopian Harrar or Sumatran Lintong, or (if the store owner is not a purist) Chocolate Mint or Irish Creme. These stores are based on the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century tradition of small stores that roasted their own coffee in a little machine behind the counter and sold it directly to the public in bulk, custom ground. A few specialty stores are direct survivors from that period, but most are the brain children of pioneering entrepreneurs who recreated the tradition with skill and passion. As the quality of mass-distributed, canned coffee declined in the 1960s and 1970s owing to the substitution of bland, cheap robusta coffee for higher-quality arabica coffees, the specialty coffee business picked up steam, first in university towns and gentrified urban pockets, then in city centers and suburban malls. From a few coffee-loving idealists scratching a living from behind pine counters, the specialty coffee world has grown to become a powerful alternative to the commercial coffee business, with a specialty coffee trade association, publications, meetings, industry giants like Starbucks, and other trappings of an established niche-occupier in modern commerce.

Caffès Despite Themselves

Espresso was not central to the interests of the early pioneers of specialty coffee, who preferred to devote themselves to delicious subtleties like the differences between Ethiopian Harrar and Ethiopian Yirgacheffe, or to the nuances of original house blends. Nevertheless, as specialty coffee stores began to accommodate their customers by adding tables, chairs, and pastries, dispensing espresso also became an important part of their business. The omnipresent Starbucks started as a small chain of classic specialty coffee stores, morphed into a mammoth chain of high-quality espresso bars, and now is intent on opening larger locations that function like genuine community coffee houses.

Even specialty stores that once did their best to avoid becoming caffè-ified, like the California-based Peet’s chain, were turned by their admirers, willy-nilly, into improvised caffès. I recall driving through North Berkeley, seeing a crowd ahead of me, and thinking that perhaps a serious accident had occurred because so many people were milling around at the edge of the street. Then I realized that they were all holding coffee cups, and that I simply had happened upon the morning crowd at the original Vine Street Peet’s store. Such, once more, is the civilizing function of coffee—it can turn even a curb and a piece of dirty sidewalk into a place to talk and be.

ESPRESSO BREAK

CAFFEINE, THE DOCTORS, AND ESPRESSO

Even bringing up health in a book on espresso may strike some readers as contradictory. Although coffee first appeared in human culture as a medicine, the kind we now patronize as “herbal,” the modern medical establishment has viewed coffee over the years with suspicion. So much so that coffee has become one of the most intensely scrutinized of modern foods and beverages.

Why has the medical establishment chosen to focus so much attention on coffee in particular? Why not on scores of other foods, from white mushrooms to black pepper to spinach, all of which have been accused of promoting various diseases? Perhaps because coffee is such an appealing dietary scapegoat. Since it has no nutritive value and makes us feel good for no reason, coffee may end up higher on the medical hit list than other foods or beverages that may offer equal or greater grounds for suspicion, but are more nourishing and less fun.

And since in its dark, syrupy richness espresso seems an intensification of the very idea of coffee, some readers also may worry that espresso is an intensification of coffee’s purported health risks.

For Now, Sip Easy

For now, however, the espresso lover can rest easy, or at least sip easy. Despite over twenty-five years of intensive study, medical science has yet to prove any definite connection between moderate caffeine or coffee consumption and disease or birth defects. For every study that tentatively suggests a relationship between moderate coffee drinking and some disease, or between moderate coffee drinking during pregnancy and a pattern of birth defects, other studies—usually involving larger test populations or more stringent controls—are published that contradict the earlier, critical studies. It is safe to say that the medical profession is further away than ever from nailing coffee with the kind of warning labels that decorate wine and beer bottles, despite continued intensive testing and study.

Nor do espresso drinkers appear to be at any greater risk than their filter-drinking colleagues. Although scientific studies of the impact of coffee on health seldom isolated variables like brewing method and style of roast, nothing in the literature so far would indicate that any characteristic specific to espresso poses special health risks, aside from the fact that it tastes so good we may be tempted to drink too much of it.

In fact, there may even be some basis for arguing that espresso is healthier, or at least less unhealthy, than the ordinary thin-bodied stuff found in restaurant carafes. The darker roasts used in the espresso cuisine contain somewhat less caffeine than lighter roasted coffees, and considerably less of the components that contribute to the acidic sensation that some people blame for their stomach problems. Furthermore, the espresso method extracts somewhat less caffeine from an equivalent amount of ground coffee than does the drip method because the brewing process happens so much faster.

However, such speculation is irresponsible at this point. Until the researchers begin to take the details of brewing method, style of roast, and serving customs (Do the tested subjects take their coffee with milk or without? With sugar or without? Do they tend to drink it on an empty stomach, or after dinner? Do they often take it with alcohol?) into account in their investigations, not only will we know nothing verifiable about the differences between espresso and filter coffee in terms of impact on health, but we probably won’t know much about the health impact of coffee generally.

Any Conclusions?

Despite all of the uncertainties, is there anything the health-conscious espresso lover should conclude from the evidence gathered so far? The following, I would argue.

1) If you are a moderate espresso drinker (that is, if you don’t regularly indulge in doubles and triples and are capable of waiting a couple of hours between servings), and are in good health, then you should relax and enjoy. Nothing has been proven against temperate coffee or espresso drinking, and for the near future at least, it appears that nothing will be.

“Coffee Comes to the Aid of the Muse,” a nineteenth-century painting, illustrates in poetic terms the short-term advantages of coffee for the creative endeavor.

On the other hand:

2) Make certain your espresso drinking is moderate. The studies that appear to exonerate coffee drinking are not exonerating the habits of mindless coffeeholics who drink ten cups a day out of the office carafe, or espresso fanatics who pour down triple lattes or double espressos at every coffee break. What is being exonerated is “moderate” intake of caffeine, usually defined as 300 to 500 milligrams per day, or the equivalent of three to five cups of American-style drip coffee (assuming the coffee drinker is not also consuming caffeinated colas or over-the-counter medicines containing caffeine).

Unfortunately, it is not clear how much caffeine a single serving of espresso packs, since espresso brewing procedures differ so widely. A properly concentrated, properly pressed 1¼-ounce serving of espresso probably contains about 80 to 100 mg of caffeine, a bit less than the average cup of filter coffee. So, following the definition of moderation in coffee drinking given above, you could consume three to four such proper servings of espresso per day and still remain safely in the “moderate” coffee-drinker category. However, the misplaced generosity of many North American espresso operators place such estimates in question, since these inexperienced zealots tend to continue pressing caffeine and bitter chemicals out of the ground coffee long after the flavor oils had been extracted. If you care about your caffeine intake and love espresso, learn to brew it yourself or patronize places that understand the espresso cuisine and press the coffee properly.

3) If you are pregnant or have certain health conditions, you should bring your coffee-drinking habit to the attention of your physician, even if it is a moderate habit. Aside from pregnancy, health conditions that merit examining your coffee drinking include benign breast lumps, high cholesterol, heart disease, osteoporosis, and some digestive complaints. Again, nothing has been proven against moderate coffee consumption in any of these situations, but overall results are ambiguous, some physicians may disagree with certain studies that exonerate caffeine, and new studies may have appeared that complicate the matter.

Finally, and above all:

4) Enjoy rather than swill. In espresso good health and good aesthetics go hand in hand. The Italian practice of stopping frequently during the day to concentrate on the brief but repeated pleasure of a single small serving of espresso is probably considerably healthier than the North American practice of carrying off triple lattes or double cappuccinos to work. Espresso drinkers who learn to appreciate the perfection of a single, correctly pressed serving of espresso, or the few fragrant ounces of a classic cappuccino, and who take the time to give themselves over to the experience of that perfection, to the moment of the coffee, to its warmth and perfume, are far less likely to abuse caffeine than are those coffee drinkers who carry around plastic foam cups of dead office coffee or half-cold caffè latte all day.

For a discussion of caffeine-free coffees turn to here. I discuss caffeine-free coffees and health issues at greater length in my book Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing, & Enjoying