5 BOURBON, PARCHMENT, AND MONSOONED MALABAR

A COFFEE BEAN PRIMER FOR ESPRESSO

The relationship between the espresso we drink and the coffee berry as it ripens on a tree on a tropical farm is both simple and complicated. The simple part is obvious: no coffee berry, no espresso. The complex part is everything else. Since the seed of the berry that ultimately becomes espresso is subject to so many complex processes between the moment it ripens and the moment its rich, dark infusion is finally drunk, tracing taste characteristics that appear in the cup back to the bean itself is a perilous undertaking, filled with caveat and equivocation.

Take, for example, a quality embodied by all good espresso: heavy body, meaning a sensation of fullness in the mouth. Starting on the distant, berry end of the process, beans from certain origins definitely do produce a fuller-bodied beverage than do beans from certain other origins. Yet does the full body of a particular demitasse of espresso necessarily mean that the coffees it comprises came from beans known for their heavy body?

Not really. A properly bewed espresso is fuller-bodied than a poorly brewed espresso, for example. Furthermore, coffee roasted either relatively lightly, as in some North American cuisine, or very darkly, as in some northern French cuisine, will produce a lighter-bodied coffee than the middle ranges of dark brown usually used for espresso. Coffees that have been subjected to decaffeination processes frequently display less body than coffees that have not been so processed. Finally, the methods by which the coffee seed has been picked, divested of its fruit, dried, cleaned, and sorted also affects body.

In attempting to make sense of these complexities, I would like to proceed systematically, first by identifying some broad taste characteristics that apply to coffee generally and espresso coffee in particular, then by describing how various factors and processes that affect the green bean influence those characteristics as they display themselves in the cup of espresso we finally drink.

PROFESSIONAL TASTING CATEGORIES

One of the most desperate acts possible in human communication is attempting to explain how something tastes to someone who hasn’t tasted it. Nevertheless, for commercial reasons and because we humans like to talk about experiences that give us pleasure, coffee professionals have come up with some terms for describing the various nuances that manifest in the taste of coffee.

First, here are a few terms and concepts used to discuss the relative merits of various green coffees. These terms describe taste characteristics associated with the bean itself. They reveal themselves most clearly in coffees brought to the relatively light roast used by professionals to “cup” coffee, or evaluate it by taste and smell.

The more romantic of these tasting terms have been carried into the prose used to sell specialty coffees; the less romantic remain the practical property of the folks who actually work in the business.

Acidity, Acidy. Acidity refers to the high, thin notes, the dryness a coffee produces at the back of the palate and under the edges of the tongue. This pleasant tartness, snap, or twist is what coffee people call acidity. In a poor-quality or underroasted coffee the acidy notes can become sour and astringent rather than brisk, but in a fine, medium-roasted arabica coffee, they will be complex, rich, and vibrant. The acidy notes also carry, wrapped in their nuances, much of the distinctiveness of rare coffees.

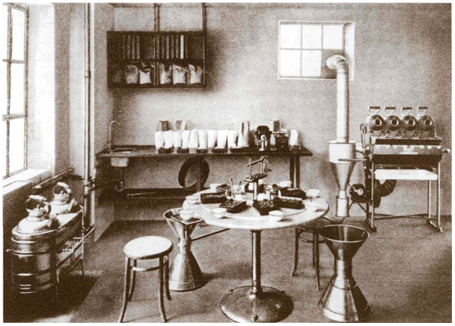

An early twentieth-century cupping room, the gustatory control center of the roasting operation. Note the small roasters on the right back wall, used to roast samples of green coffees, and the rotating tasting table, flanked by hourglass-shaped spittoons (the coffee-cupping ritual involves sucking the coffee noisily from a spoon, swishing it about the mouth, and spitting it out.) Contemporary cupping rooms differ from this one only in detail.

You will not run into the terms acidity or acidy in your local coffee seller’s signs and brochures. Most retailers avoid describing a coffee as acidy for fear consumers will confuse a positive acidy brightness with an unpleasant sourness. Instead you will find a variety of creative substitutes: bright, dry, brisk, vibrant, etc.

The darker the style of roast, the less distinct the acidy notes will be. In the medium dark brown roasts used in Italian-style espresso cuisine, the acidy notes may continue to reveal themselves, although much less distinctly than in medium roasts. In the dark brown roasts used in most American espresso cuisine, the acidy sensation will have been almost entirely roasted out of the bean.

Body. Body or mouth-feel is the sense of heaviness, richness, and thickness when the coffee is swished around the mouth. To pursue a wine analogy, cabernets and certain other red wines are heavier in body than most white wines. In this case wine and coffee tasters use the same term for a similar sensation, although the chemical basis for the sensation differs between wine and coffee.

Coffees from various parts of the world vary in body. Many celebrated coffees are typically heavy in body; the best Indonesian coffees are particularly so. However, as I indicated earlier, in espresso the roasting and brewing processes have considerably more effect on body than the characteristics of the original green bean. Virtually every detail of advice and prescripiton on espresso brewing offered here has to do with maximizing body and richness in the final cup.

Aroma. Some coffees may be more aromatic than others, and some may display certain distinctive characteristics more clearly in aroma than in the cup. Typical positive characteristics associated with aroma are subtle floral and fruit tones and vanilla, nut, and vanilla-nut notes.

Again, however, the dark-roasting involved in espresso cuisine mutes such subtleties, partly replacing them with the more general aromatics encouraged by the dark roast, like chocolate and bittersweet notes. Nearly black roasts may display little aroma of any kind except the charcoal pungency of the blackened bean, since virtually all of the delicate aromatic oils will have been burned off.

In the brewing process aroma is particularly promoted by freshness. The more recently the coffee has been roasted and ground, the more powerful the aroma. Once liberated in the cup aroma fades quickly, which is why the little cups used for straight espresso are preheated and the drink consumed quickly.

Finish and Aftertaste. If aroma is the overture of the cup, then finish is the final flourish at the end of the piece and aftertaste the resonant silence thereafter. Both are extremely important characteristics for anyone who genuinely, sensually enjoys coffee. The sensations of a fine coffee perfectly brewed shimmer on our palate in a long, exquisitely fading trajectory, sometimes for an hour or two after we finish the cup. Any weakness or defect in flavor will be similarly and regrettably persistent.

Generally, heavy-bodied coffees have longer and more resonant finishes and display a more persistent aftertaste than lighter-bodied varieties. But once again, in espresso cuisine brewing and roasting may have considerably more impact on finish than the qualities of the bean itself. Freshness in particular affects finish. A freshly roasted and ground espresso coffee will display a much more vibrant finish than coffees that have partly staled.

Flavor. Flavor is the most ambiguous of the tasting categories defined here because it overlaps all of the others. Terms describing positive flavor tones or notes: floral, fruity, vanilla-like, nutty, vanilla-nut-like, chocolaty, caramel, spicy, herby, tobaccoish, pungent. General terms describing flavor include complex, balanced, deep, ordinary, bland, inert, imbalanced, rough. The primary tastes (sweet, salt, sour, bitter) also come into play. Sweetness in particular is a strong modifying influence on other cup characteristics. Natural sweetness is a sign of quality in any coffee, but is a particularly important characteristic for coffees intended for the espresso cuisine. Sweetness indicates that the coffee fruit was picked when ripe and processed with care.

Varietal Distinction. If an unblended coffee has characteristics that set it off from other coffees yet identify it as what it is, it has varietal distinction. A rich, winy-fruit acidity characterizes Yemen and many good East Africa coffees, for example, whereas a low-toned pungency is a distinctive characteristic of most good Sumatra coffees. But, again, the darker roasting in the espresso cuisine mutes most varietal distinctions.

Flavor Defects. These are unpleasant taste sensations created by problems in picking the coffee fruit, removing the fruit from the beans, or drying and storing the beans. Most decent espresso blends are free of flavor defects, but occasionally a coffee sneaks into a blend sufficiently defective to sound a discordant note. The names for defects are numerous, but by the time they emerge in a demitasse of espresso they typically fall into one of two broad categories: ferment, the taste of rotten fruit (caused by the fruit fermenting while in contact with the bean), or hardness or harshness, a sort of aggressive flatness caused by molds or mustiness. Defects sound their unpleasant notes most clearly in aroma and aftertaste.

ESPRESSO TASTING TERMS

The following terms often come up informally in discussions of espresso coffees, though more as terms of connoisseurship than of trade. They relate as much to the effects of brewing and roasting as to the qualities of the original green bean and are less clearly defined than the technical tasting terms defined earlier.

Sweetness. The sensation this term describes is not the brassy monotone of refined white sugar, but rather a vibrant natural sweetness shimmering inside and around other positive sensations. Sweetness in an espresso is owing to inherently sweet beans that have been produced only from ripe fruit, to a tactful roast style that caramelizes the sugars in the bean rather than burning them, and to proper brewing technique.

Bitterness. The bitter bite of some espresso coffees should be distinguished from the acidy tones of a medium-roast coffee, since the bitterness described here is a taste characteristic encouraged by dark roasting. It is not an unpleasant characteristic. Most West Coast American and many Latin American blends are bitter by design. Espresso drinkers in these regions find the lighter-roasted, sweeter espresso blends preferred by northern Italians bland by comparison. If the distinction between bitter and acidy seems abstract, an analogy might help. Acidity is like the dry sensation in most wines, a mild astringency balanced by sweetness. The bitter sensation that arises from dark roasting is more analogous to the bitterness of certain apertitifs like Campari, for example; it is a more dominating sensation, and less localized on the palate.

The average North American filter-coffee drinker will call bitter tones “strong,” to my mind an inappropriate term. Strong properly refers to the amount of solids and other flavoring agents in the brewed coffee. A dark-roasted coffee could be brewed strong, as it is in the espresso method, or weak, as it might be in a filter-drip system when someone has been stingy with the ground coffee.

Pungency. My word for the pleasant, sweet-yet-twisty tones of a good West Coaast–style American espresso blend. If there is a Peet’s coffee store near you, go in and sniff the coffee bins for a suggestion of the sensation I am describing. This aroma complex is seldom encountered in Italian espressos, but is a common characteristic of North- and Latin American blends. It is apparently created by a dark roast achieved slowly. Bitterness might be another word for it.

Smoothness. I take smooth to be an epithet describing an espresso coffee that can be taken comfortably without milk and with very little sugar, a coffee in which a heavy body and the sweet sensation described above predominate over bitter and acidy tones.

WHAT MAKES GREEN BEANS DIFFERENT

If green coffee beans embody differing taste characteristics, what causes these differences? The following pages describe factors influencing coffee quality and flavor in the green bean before it has been subjected to subsequent processes like blending, roasting, decaffeination, and brewing.

Botany

Species. All of the world’s finest coffees, and some that are not so fine, belong to the species Coffea arabica, the species that first hooked the world on coffee. Second in commercial importance among coffee species is Coffea canephora or robusta, a lower-growing, more disease-resistant, heavier-bearing species of the coffee tree. Robusta produces a bean that is rounder in shape than the arabica bean, blander in flavor, heavier in body, somewhat heavier in caffeine content, and cheaper than most Arabica. Coffee from the robusta species is widely used in cheaper commercial canned blends and instant or soluble coffees, but has little importance in the world of fancy single-origin coffees. High-quality robustas may be used in small quantities in some Italian espresso blends because of their heavy body. Others of the hundreds of known coffee species, particularly Coffea liberica, are grown commercially, but are not important in the larger picture. What have become important are some recently developed, controversial hybrid varieties of Coffea arabica, such as var. catimor, that include some robusta in their parentage.

Variety. Just as there are McIntosh apples and Golden Delicious apples, Cabernet wine grapes and Merlot wine grapes, there are various botanical varieties or cultivars of Coffea arabica. Some of these varieties are long established and traditional, the kind of varieties that gardeners call heirloom. They are the product of happy coincidence, of a process of spontaneous mutation and human selection that may have taken place decades, sometimes centuries, ago. These heirloom varieties, or old Arabicas as they are called in the coffee world, include var. typica, the original variety cultivated in Latin America; the famous var. bourbon, which first appeared on the Island of Reunion (then Bourbon) in the Indian Ocean in the eighteenth century; the odd and rapidly disappearing var. maragogipe (Mah-rah-go-ZHEE-pay), which produces a very large, porous bean and first appeared in Maragogipe, Brazil. In addition, there are many noble varieties that are grown only in the regions where they first appeared. These locally based varieties include the var. lintong, which produces the finest coffees of Sumatra; the Ismaili and Mattari cultivars of Yemen; and the almost vanished var. old chick of India.

Coffees from such traditional varieties are particularly valued in the fancy coffee world. In recent years green-revolution scientists working in growing countries have produced varieties of arabica that are more disease-resistant, heavier-bearing, and faster to reach maturity than the older, traditional varieties. Two of the most controversial of these so-called new Arabicas are the Colombiana or Colombia (developed and widely planted in Colombia) and the sinister-sounding Ruiru 11 (Kenya).

Coffee professionals in the United States are almost unanimous in condemning all such new hybrid varieties for lacking the complexity and nuance of their beloved old arabicas. However, the flavor issue is much more complex than many coffee professionals would have us believe. There is no doubt that coffee from different varieties tastes different, even when the trees are grown on the same soil under the same conditions. But are the old arabicas always better tasting than the new? Not consistently. Cup quality seems to depend on a complex, often unpredictable interaction of variety and local growing conditions. The classic Typica variety that produces the celebrated Kona coffees of Hawaii has turned out to be a taste bust when planted on other Hawaiian islands under different growing conditions from Kona. Bourbon, the traditional premium variety of Brazil, seems consistently more complex and interesting in the cup than newer varieties when grown in Brazil. But will seeds of those Bourbon trees, in growing situations other than Brazil, necessarily produce coffee with similar superiority? Perhaps. Perhaps not. I recently organized a blind tasting of El Salvador coffees in which a relatively recently developed hybrid called Pacamara scored better than a Bourbon from the same farm.

The situation is further complicated by the existence of varieties that, like the old arabicas, are spontaneous mutants, but which did their mutating at a relatively recent date in history. They include the widely planted var. caturra (1935) and var. mundo novo and var. Kent.

By now my point should be clear: there are no big, simple answers in respect to variety, only little answers and passionately held positions. Interested aficionados can only stay tuned.

Altitude

The arabica species grows best at altitudes ranging from around 1,500 to 6,000 feet. Generally, the higher grown the coffee the more slowly the seed, or bean, develops, and the harder and denser the bean. Such high-grown or hard-bean coffees are valued in the fancy coffee market because generally they display a heavier body, a more complex flavor, and a more pronounced and vibrant acidity than lower-grown coffees.

However, these high-grown, acidy coffees are a bit overbearing for many people’s palates, and they most definitely do not make the best espressos. The espresso brewing system produces a highly concentrated coffee that intensifies certain taste characteristics like acidity. For this reason powerfully acidy coffees may be too sharp for espresso blends and can imbalance the cup. Some of the most sought-after coffees for espresso blending are lower-grown, sweeter coffees like the best coffees of Brazil.

Picking, Processing, and Drying

The care with which coffee is picked, the manner in which the fruit is removed from the bean, and the way in which the bean is dried after removal of the fruit all profoundly affect coffee taste and quality.

Picking and Sorting the Fruit. Coffee fruit does not ripen uniformly. Both ripe and unripe berries, or cherries as they are called in the coffee trade, typically festoon the same branch. The best coffees are handpicked as they ripen. Cheaper coffees are stripped from the trees in a single operation, thus combining ripe, unripe, and overripe berries, not to mention leaves, twigs, and dirt, in the same batch. Somewhere between selective handpicking and strip picking is machine picking, in which rods vibrate the tree branches just enough to cause ripe cherries to drop off the tree. Growers often try to compensate for machine or strip picking by careful mechanical separation of ripe cherries from less ripe and overripe. Although such post-picking sorting can partly compensate for failures in picking, the sweetest and finest coffees continue to be produced from cherries that have been selectively handpicked.

Removing the Fruit from the Bean. Common wisdom in the coffee trade declares that wet processing, in which the outer layers of the coffee fruit are carefully removed from the seed or bean in a complex set of operations before the bean is dried, produces the best coffee. The same wisdom declares that dry-processed or natural coffee, in which the fruit and skin are allowed to shrivel and dry around the bean, then later removed by abrasion, is inferior to such wet-processed or washed coffee. This generalization overlooks the fact that many of the world’s most interesting coffees are either dry-processed (Yemen mocha for example), or processed in a way that combines wet- and dry-processing (most Sumatra coffees).

At the left a coffee tree; in the center a coffee branch, with flowers near the top of the branch modulating to ripe fruit near the bottom. At right are representations of the coffee flower, which is white in color, and below that illustrations showing how the coffee seed or bean is nestled inside the coffee fruit.

What really counts is the care taken in processing the coffee, regardless of method. Many dry-processed coffees are also strip picked and carelessly handled, which means that overripe, rotting fruit and other vegetable matter (not to mention whatever animal matter happens to be on the ground at the time) may be piled together during the drying process, tainting the flavor of the entire batch. Such practices have given dry-processing an undeservedly bad reputation.

In fact, coffee that has been dry-processed with care often makes the best espresso. Good dry-processed coffees often display a sweeter, deeper, more complex flavor than the cleaner but more transparent taste of wet-processed coffees, probably owing to the effect of the fruit drying around the bean. Italian roasters almost unanimously prefer dry-processed Brazil coffees for their espresso blends.

Cleaning and Sorting the Beans. In general, the more care taken in removing various unwanted material—stones, twigs, discolored or immature beans, and the like—from the sound coffee beans, the cleaner and fuller the flavor of the coffee will be and the higher price it will command. The cleaning and sorting process can be done by machine, by hand, or by some combination of both.

Grading. Grading is a process that assigns value to coffees for purposes of trading. It ultimately is a kind of sophisticated sorting that divides a given growing region’s coffee production into categories according to various quality-related criteria. These criteria vary from country to country, but typically include number of defects (including everything from broken or misshapen beans to sticks), size of the bean (bigger is usually better because bigger beans come from riper fruit), growing altitude (higher is usually better), method of processing (wet vs. dry), and cup quality.

Age of the Beans

Coffees that are roasted and sold soon after processing are called new crop and generally display more acidity, brighter, clearer flavor notes, and a thinner body than old crop coffees, which have been held in warehouses for a year or two before roasting; mature coffees, which have been held for two to three years; or vintage or aged coffees, which have been held for several years. The longer coffees are held, the heavier their body and the more muted their acidity becomes, until, in aged or vintage coffees, the acidity and other subtle aromatics disappear altogether to be replaced by a rather static heaviness. Unfortunately, many aged coffees now sold in the United States seem to display a hard taste along with the desirable heaviness, perhaps owing to contact with excessive moisture during aging. Aged coffees are sometimes used in premium espresso blends to balance younger, brighter coffees.

Monsooned Malabar is a special kind of coffee produced in India by exposing dry-processed arabica coffees to monsoon winds in open warehouses. The ambient moisture seems to partly replace the original moisture in the bean, producing a coffee that is monotoned, pungent, and heavy-bodied. Some espresso blenders use Monsooned Malabar to anchor the bottom notes of their blends.

Soil, Climate, and Other Geographic Intangibles

Certain coffees are world famous: Jamaica Blue Mountain, for example, and Hawaii Kona. Others should be, such as Ethiopia Yirgacheffe and the best Kenya coffees. Such coffees, which are grown in certain limited geographical areas, may display distinct flavor characteristics that coffee fanciers admire. Yirgacheffe is light-bodied, flowery, and fruity; the best Kenya AA displays a deeply dimensioned acidity alive with winelike and berry notes.

Such differences in flavor characteristics are undoubtedly owing to a combination of factors, including botanical species and variety, altitude, and method of picking and processing. Clearly, however, local climate and soil are primary determining factors in determining regional flavor characteristics.

There are even more elusive environmental influences on coffee taste than those determined by region: east-facing slopes versus west-facing slopes, for example; subtle local variations in rainfall; local differences in soil composition. I have tasted coffees from farms in the Kona district of Hawaii that were dramatically different in cup characteristics from coffees grown on farms at the same altitude only a half mile away.

Such distinctions are wonderfully interesting (if baffling) but are less important in the world of espresso than the world of fine coffees intended for drip brewing. Nevertheless, some of the unique flavor notes of the world’s most distinctive coffees are integrated into the finest espresso blends, stretching the range and complicating the final flavor profile.

BLENDS AND BLENDING

Blends can combine coffees brought to different degrees of roast, coffees with different caffeine contents, and/or straight coffees from different origins.

For example, roasters frequently blend darker and lighter roasts to produce a more complex flavor than can be obtained with coffees brought to the same degree of roast. Blending also is used to modulate caffeine content: caffeine-free and ordinary beans are often combined in varying proportions to produce blends with half the caffeine in ordinary coffee, or two-thirds, or one-third, etc.

Much more common, however, and more challenging, is blending coffees of approximately the same caffeine content and roast, but from different origins. As practiced in the supermarket canned and instant coffee business, such blending aims to keep costs as low as possible while maintaining a consistent, if lackluster, flavor profile. Specialty or fancy coffee roasters also may blend for price, but with less urgency and compromise. The overriding goal of specialty blenders is simply producing a coffee that is more complete and pleasing in its totality than any of its unblended components would be alone. This goal is particularly important in espresso, because the concentrated cup produced by the espresso brewing method tends to reward balance and completeness rather than the often interesting but imbalanced flavor profiles of coffees from single origins.

Complete and Pleasing?

In the case of an espresso blend, what constitutes “more complete and pleasing” is obviously relative: relative to the palate of the blender, to the expectations of the consumer, and to the traditions to which both blender and consumer refer.

At this point it might be useful to refer to the array of tasting terms listed earlier: acidity, body, aroma, finish, sweetness, bitterness, and so on.

It would be safe to say that all espresso blends everywhere aspire to as full a body as possible, as much sweet sensation as possible, and as much aroma and as long and resonant a finish as possible. The differences arise with acidity and with the bitter side of the bittersweet taste equation.

Most northern Italian roasters present blends with almost no acidy notes whatsoever, whereas North American espresso blends often maintain some of the dry, acidy undertones most Americans and Canadians are accustomed to in their lighter-roasted coffees. This difference is simply a matter of choice and tradition. North Americans are used to acidy, high-grown Latin American coffees, and Italians are accustomed to drinking either African robustas or lower-altitude Brazil arabicas.

My own position, for what it’s worth, is that acidy notes need to be felt but not tasted in espresso blends. They should be barely discernible, yet vibrating in the heart of the blend.

Recall that acidity, or dryness, is a property of the bean that diminishes as the roast becomes darker, to eventually be replaced entirely by the bittersweet, pungent flavor notes characteristic of dark roasts. The value of the bitter side of the bittersweet equation is also an issue in blending philosophy, with Italian and Italian-style roasters coming down more on the sweet side, and North American roasters more on the bittersweet. As I pointed out in discussing style of roast, this difference is reflected in the somewhat lighter roasts preferred by Italian roasters, opposed to the darker styles favored by most North American roasters.

So, on both accounts, blending philosophy and style of roast, northern Italians put a premium on sweetness and smoothness and North Americans on punch.

It is clear why North Americans might prefer a punchier, more pungent and more acidy espresso coffee: They need the power of such flavor notes to carry through all of the milk they tend to add to their lattes and cappuccinos. Italians generally take their espresso undiluted and so might logically prefer a smoother, sweeter blend. But such an explanation may be entirely too rational. After all, those purist Italians also tend to dump large quantities of sugar into their smooth, sweet espresso blends. Probably taste in espresso blends is simply another irrationality of culture and tradition.

Achieving Blending Goals

At any rate, if heavy body, seductive aroma, a muted acidty, and (in the case of American-style espresso blends) sweet-toned pungency are the goals, how does one attempt to achieve these goals in blending?

In general, roasters choose one or more coffees that provide a base for a blend, additional highlight coffees that contribute brightness, energy, and nuance, and (often but not always) bottom-note coffees that intensify sensations of body weight.

Base Coffees. Coffees that provide the base for espresso blends should not be neutral, at least not in my view. They definitely should not be dull or bland. They should be agreeable, without distracting idiosyncrasy or overly aggressive acidity, round and sweet, and they should take a dark roast well. The classic base for espresso is Brazil coffees that have been dry-processed, or dried inside the fruit, a practice that promotes sweetness and body. Peru and some Mexico coffees (all of which are wet-processed) also make a gentle but lively base for espresso. Coffees from the Indonesian island of Sumatra are favorite base coffees among many West Coast–style American blenders. Like Brazils, Sumatras are low-keyed, rather full-bodied coffees, but brought to a dark roast they tend to be bittersweet and pungent, qualities suited to the dark-roasted, sharp, milk-mastering blends favored caffè-latte-happy West Coasters.

Highlight Coffees. These may be any coffee with character, energy, and power. Kenya, with its resonant dimension and winelike acidity, is a favorite highlight coffee among American blenders. Other blenders may prefer the round, clean power of good Costa Ricas, the twistier, often fruit-toned energy of Guatemala Antiguas, or the singing, floral sweetness of washed Ethiopias.

Bottom-Note Coffees and the Robustas Controversy. Blenders often add coffees whose primary contribution to the cup is weight and character. Bottom-note coffees are particularly important in espresso, where resonance and body are paramount. Sumatra Mandhelings are sometimes used as bottom-note coffees, as are specially handled coffees like India Monsooned Malabar and aged coffees. The most controversial bottom-note coffees are the heavy but inert coffees of the robusta species. Italian blenders use robustas freely in their espresso blends to promote body and the formation of crema, the golden froth that covers the surface of a well-made tazzina of espresso. North American blenders use robustas in their espresso blends very sparingly, if at all. I have waffled about the value of robustas in espresso blends over the years, but at this moment I am a robusta naysayer. To my palate robustas are simply too dull and lifeless. They may contribute body, but in return they tend to suck life out of a blend, absorbing nuance and deadening the profile.

CAUSE COFFEES: FOR EARTH, BIRDS, AND PEOPLE

In recent years an expanding array of environmentally friendly, socially progressive, migratory bird–friendly, variously issue-oriented coffees have stepped forward to make their case to right-minded coffee lovers. These cause coffees are less prominent in the world of espresso than in the world of fancy single-origin coffees, probably because the focus in espresso is more on the drama of the drink and less on the coffee itself.

Nevertheless, espresso drinkers can be as concerned as anyone else about health, environment, and social issues, so here is a much condensed list of issue coffees and their related causes and controversies. For a more thorough discussion of these coffee categories and the issues animating them, consult the companion volume to this one, Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing, & Enjoying.

Organically Grown Coffees. The granddaddy of environmentally correct coffees, “organics” are certified by independent agencies to have been grown and processed without use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides. Organic growing methods usually produce less coffee per acre, and lower yields plus the cost of certification mean growers face higher costs, which translate to higher retail prices for organically grown coffees. Is the extra cost worth it?

The health benefits of organic coffees for consumers are probably minor. Remember that we don’t eat the fruit of the coffee tree as we do the fruit of an apple tree. Instead we use only the seed of the fruit, which is dried, roasted at very high temperatures, and infused in hot water. Then we throw the remnants of the seed away and drink the water. Thus, it would seem that eating organic apples or carrots is far more important to our health than drinking organic coffee.

Furthermore, many coffees are de facto organic because the peasant growers have never been able to afford chemicals in the first place. To cite three well-known examples, it is unlikely that most Yemen, Ethiopia, or Sumatra coffees have been anywhere near expensive manufactured agricultural poisons or supplements.

However, it also is certain that, on the growing end of things, organic growing procedures are of enormous benefit: to air, to earth, to animals, to people. It is more for environmental and social reasons that many coffee lovers are willing to spend a penny or two more per cup for a certified organically grown coffee.

Shade-Grown Coffees. In many places in the world coffee is traditionally grown under a canopy of shade trees. Coffea arabica orginally grew wild in the shade of the mountain forests of central Ethiopia, and in many (but not all) coffee-growing regions of the world shade has proven to be essential in protecting coffee from the parching effect of the tropical sun. Recently, studies have begun to show the importance of these shade canopies to everything from sheltering migrating birds to slowing global warming. But just as the awareness of the importance of coffee shade canopies is sinking in, shade-growing fields in many parts of the world are being rapidly replaced by fields of hybrid coffee varieties that grow well in full sun.

These two developments—on one hand, the understanding of how important shade-coffee canopies are to the environment; on the other, the trend toward growing coffee in full sun—has led to marketing of shade-grown and bird-friendly coffees. Audubon Society chapters have been particularly active in supporting shade-grown coffees that offer crucial shelter to songbirds on their migrations through Central and South American coffee-growing countries.

The bureaucratic machinery necessary for defining and certifying “shade-grown” coffee is in the process of development. Currently the Smithsonian Institution licenses certified organic coffees that also meet Smithsonian criteria for growth under a biodiverse shade canopy. Such ultimately environmentally correct coffees are permitted to use the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center’s “Bird Friendly” trademark. Until additional clear certification procedures are in place, bird lovers (not to mention oxygen lovers) will have to take the word of the seller that other, noncertified-organic coffees are indeed shade-grown.

The entire idea of certifying shade-grown coffee is wildly controversial among some coffee growers and exporters because in many parts of the world coffee is traditionally not grown in shade. These traditional full-sun growing regions are often so wet and humid that the coffee trees need full sun, or so far from the equator that trees grown in shade become leggy. The world’s first commercial coffee, Yemen mocha, has been grown in full sun for four hundred years. Other traditional sun-grown coffees include Hawaii Kona, Jamaica Blue Mountain, Sumatra Mandheling, and all Brazil coffees. Critics of shade-grown certification argue that the real target should be those growers who switch from shade to sun, not those who have grown their coffee in full sun for generations.

Fair-Traded and Other Socially Responsible Coffees. The majority of the world’s coffee is grown by peasant farmers on small plots. Few of these farmers receive anything close to a decent price for their coffee, while fine coffee itself remains a dramatically underpriced beverage. The world’s most expensive coffee, brewed at home, costs less per ounce than Coca-Cola.

From that preamble readers may suspect that I am a supporter of any system that helps return some of the money we pay for coffee back to the peasant growers who, essentially, suffer grinding poverty so that relatively wealthy Americans can pay a few cents less per pound for an already underpriced luxury.

A Fair Trade Certified seal on a coffee means that growers, usually small peasant growers, have been paid a reasonable, formula-defined price for their coffee. The fair-trade movement is quite prominent in Europe, less so in the free-trading, price-busting United States. More typical in the United States are arrangements between individual roasters and groups of peasant growers that return a percentage of the retail price of a coffee directly back to the growers to support development projects ranging from clinics and schools to new roads and mills. Such arrangements are well advertised by the roasters who sponsor them, and often extend to coffees suitable for espresso cuisine.

Sustainable Coffees. Readers may wonder why all of these environmentally and socially concerned coffee folk don’t join together in common cause. After all, aficionados who seek quality have a lot in common with the birders who support shade-grown coffee, since the traditional varieties of arabica that aficonados admire are often grown in shade, while the despised new hybrids are typically grown in full sun.

Just such a big-tent approach to conscience coffees is underway. It’s called the sustainable coffee movement, and tries to bring together everyone from cranky connoisseurs to birders, health fanatics, and social progressives.

One, perhaps limited, version of the sustainable vision has been advanced by the Rainforest Alliance, whose eco-OK seal certifies that Eco-OK inspectors have found that qualifying coffee farms and mills meet a wide variety of environmental criteria, including wildlife diversity, nonpolluting practices, and responsible and limited use of agrochemicals, as well as social and economic criteria that support the welfare of farmers and workers.

Unfortunately, the current sustainable movement offends some supporters of organically grown coffees, who feel that the sustainable idea is a warm, fuzzy rip-off that dilutes everything they have worked for. It also bothers quality-oriented purists, who feel that the only criteria for selling coffee should be how good the coffee tastes in the cup. Time will tell whether the inclusive goals of the sustainable movement can be turned into a practical system with clear and verifiable criteria satisfactory to its many passionate voices and communities.

ESPRESSO BREAK

DECAFFEINATED COFFEES

The Garden without the Snake

Decaffeinated, or caffeine-free, coffees have had the caffeine soaked out of them. Most specialty roasters offer a variety of decaffeinated dark-roast coffees suitable for espresso cuisine.

Coffee is decaffeinated in its green state, before the delicate oils are developed through roasting. Hundreds of patents exist for decaffeination processes, but only a few are actually used.

The trick, of course, is how to take out the caffeine without also removing the various components that give coffee its complex flavor.

TRADITIONAL OR EUROPEAN PROCESS

In the process variously called the solvent process, European process, traditional process, or conventional process, that trick is accomplished through the use of a solvent that selectively unites with the caffeine. There are two variants to the solvent approach.

The direct solvent process opens the pores of the beans by steaming them and applies the solvent directly to the beans before removing both solvent and caffeine by further steaming.

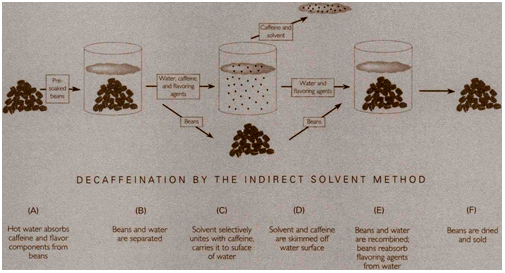

The indirect solvent process first removes virtually everything, including the caffeine, from the beans by soaking them in hot water (in the diagram here), then separates the beans and water and strips the caffeine from the flavor-laden water by means of the caffeine-attracting solvent. The solvent-laden caffeine is then skimmed from the surface of the water, and the water, now free of both caffeine and solvent, is reunited with the beans, which soak up the flavor components again. The beans are then dried and sold.

With both direct and indirect solvent methods the caffeine is salvaged and sold to makers of pharmaceuticals and soft drinks.

Solvents currently in use are methylene chloride and ethyl acetate. Neither has been fingered as a health threat by the medical establishment, although methylene chloride has been implicated in the depletion of the ozone layer. Ethyl acetate is found naturally in fruit, so you may see coffees decaffeinated by processes making use of it called natural process or naturally decaffeinated.

Note that both methylene chloride and ethyl acetate evaporate very easily. Even if small amounts of solvent remain in the beans, it is highly unlikely that significant residues survive the high temperatures of the roasting and brewing processes that occur before the coffee is actually drunk. Nevertheless, consumers’ almost metaphysical fear of such substances has led to the commercial development of alternative processes.

SWISS-WATER OR WATER-ONLY PROCESS

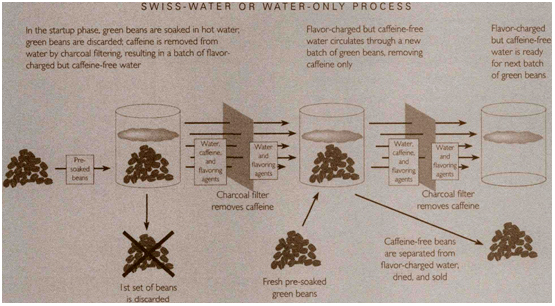

There are two phases to this commercially successful process. In the first, start-up phase (see the diagram here), green beans are soaked in hot water, which removes both flavor components and caffeine from the beans. This first, start-up batch of beans is then discarded, while the caffeine is stripped from the water by means of activated charcoal filters, leaving the flavor components behind in the water and producing what the Swiss-Water Process people call “flavor-charged water”—water crammed full of the goodies but without the caffeine. This special water becomes the medium for the decaffeination of subsequent batches of green beans.

When soaked in the flavor-charged but caffeine-free water, new batches of beans give up their caffeine but not their flavor components, which remain more or less intact in the bean. Apparently the water is so charged with flavor components that it can absorb no more of them, whereas it can absorb the villainous caffeine.

Having thus been deprived of their caffeine but not their flavor components, the beans are then dried and ready for sale, while the flavor-charged water is cleaned of its caffeine by another run through charcoal filters and sent back to decaffeinate a further batch of beans.

The problem with this process for specialty coffee roasters is the fact that the flavor components of various batches of beans may become a bit blurred. If your coffee is an Ethiopia, for example, and yesterday’s batch was a Colombia, it may be hard to determine exactly whose flavor components actually inhabit the bean at the end of the process. Your Ethiopia may end up with a little of yesterday’s Colombia in it, whereas tomorrow’s Costa Rica may end up with a little of your Ethiopia, and so on.

The Swiss-Water people have various ways of correcting for this problem, however, and over the years have steadily improved the quality of their product. This success, combined with the encouraging fact that no solvent whatsoever is used in the process and the reassuring ring of “Swiss-Water,” with its associations of glaciers, alpine health enthusiasts, and chewy breakfast cereal, have combined to make this process the most popular of the competing decaffeination methods among specialty coffee consumers.

CARBON DIOXIDE OR CO2 PROCESS

In this method, the green beans are bathed in highly compressed carbon dioxide (CO2), the same naturally occurring substance that plants consume and human beings produce. In its compressed form the carbon dioxide behaves partly like a gas and partly like a liquid, and has the property of combining selectively with caffeine. The caffeine is stripped from the CO2 by means of activated charcoal filters.

CAFFEINE, FLAVOR, AND DECAFFEINATION PROCESSES

Since caffeine in itself is tasteless, coffee flavor should not be affected by its removal. However, in the process of its removal, coffee beans are subjected to considerable abuse, including (depending on the process) prolonged steaming and exposure to solvent or soaking in hot water and/or liquid CO2. Consequently, most caffeine-free coffees are difficult to roast, and in general display somewhat less body and aroma than similar untreated coffees. You can, of course, create blends of treated and untreated beans, thus cutting down on caffeine intake while maintaining full flavor and body in at least one component of the blend.