9 ESPRESSO AT HOME

PRODUCING THE DRINKS

A look at the list of beverages in the classic and contemporary American espresso cuisines given here is an excellent place to start in assembling drinks at home. Remember, however, that much of the jargon attached to the various caffè drinks may be irrelevant in your kitchen, where the goal is simply to produce something you and your guests will enjoy, regardless of what it is called.

Before assembling espresso drinks, you may wish to look through the Espresso Breaks on selecting coffee (here), brewing the coffee (here), and frothing the milk (here).

INGREDIENTS AND RECEPTACLES

Milk. Classic espresso cuisine uses whole milk for drinks like cappuccino and caffè latte. However, North Americans have pressed virtually every other liquid dairy and pseudo-dairy product into use: nonfat milk, 1 percent milk, 2 percent milk, extrarich milk, half and half, whipping cream, chocolate-flavored milk, soy milk, and (seasonally one hopes) commercial eggnog. With the proper technique, all will froth nicely, though the fattier versions of milk may be somewhat easier to froth for beginners using standard apparatus. To my taste, skim milk is too watery, and whipping cream too flat and fatty-tasting for the espresso cuisine. I suggest you try whole or 2 percent milk first and work your way up or down in fat content from there.

Whipped Cream. The whipped cream used in the best North American and Italian caffès is never canned and seldom sweetened. A generous dollop of it is laid on top of the drink. Customers then sweeten to taste. I suggest you begin as the caffès do, with proper whipped cream, unsweetened. You can always turn to substitutes for reasons of diet or convenience later, after you have experienced the basic cuisine.

Flavorings and Garnishes

The main flavorings used in espresso cuisine can be usefully divided into three categories:

• Traditional, “natural” flavorings used in the classic cuisine: the lemon peel in espresso Romano and the chocolate concentrate in a “real” caffè mocha, for example.

• Various garnishes sprinkled over frothed milk: in the traditional cuisine unsweetened chocolate and possibly cinnamon, but in the contemporary North American cuisine a variety of other powders and spices, some sweetened and some not.

• Italian-style syrups originally designed to flavor soft drinks, but increasingly used to flavor caffè latte and other espresso drinks made with frothed milk.

Flavorings in the Traditional Cuisines. The only flavorings the traditional espresso cuisines propose are simple to the point of austerity: a twist of lemon peel with straight espresso (espresso Romano), a dash of unsweetened chocolate powder over the frothed milk of a cappuccino, or a serving of concentrated hot chocolate in the Italian-American caffè mocha. In wildly experimental moments, the purist may substitute a twist of orange or tangerine peel for the lemon, or sprinkle cinnamon instead of chocolate on a cappuccino.

The chocolate powder used in the traditional cuisine should be unsweetened but as powerful and perfumy as possible. Most coffee specialty stores now sell a good version of this ingredient. A recipe for the concentrated hot chocolate used in the traditional caffè mocha is given later in this chapter under the heading for the drink.

Garnishes. Garnishes sprinkled over the head of frothed milk that covers the surfaces of drinks like cappuccino and caffè latte have become a ubiquitous part of North American espresso cuisine. They originated with the Italian practice of garnishing cappuccino with a light dusting of unsweetened chocolate powder, but North Americans now have extended the practice to include most drinks made with frothed milk and an increasing variety of powdered and grated spices and flavorings.

The unsweetened chocolate of the Italian cuisine is often replaced by a sweetened chocolate, for example, and some use Mexican chocolate, a sweetened, spiced chocolate sold in cake form that must be grated over the frothed milk. Still others prefer to grate or shave baking chocolate—unsweetened, semisweet, or white—over their frothed milk drinks. A good cheese grater works well.

To my knowledge cinnamon is never used in Italy to garnish coffee. It has a long history in North American spiced coffee drinks, however, so it inevitably made an early appearance as a garnish in the American espresso cuisine. For my part, I don’t like cinnamon with espresso; I find that it doesn’t harmonize with the dark tones of the coffee.

Like everything else about the exuberant contemporary American espresso cuisine, garnishes know no limits. At a Seattle espresso cart I once counted twelve garnishes available for patrons to sprinkle over their frothed-milk drinks, including sweetened and unsweetened chocolate powders, vanilla powder, orange powder, cinnamon, powdered nutmeg, and fresh nutmeg (presented with grater). The cart owner claimed that one man used every one of these garnishes on his caffè latte. Garnish madness appears to have peaked, however. Most Seattle espresso establishments now restrict themselves to chocolate, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Of the various exotic garnishes I’ve tried the only one that has impressed me is the unsweetened vanilla powder, but if you like variety carry on.

Flavored Syrups. It was inevitable that the Italian-style fountain syrups that for so many years spread their tantalizing rainbow of colors and flavors across the back bars of caffès would break out of their limited role as soft-drink flavors and begin to find their way into coffee drinks. They are usually used to flavor tall, milky drinks rather than straight espresso, where more subtlety is called for. The flavored caffè latte in particular has become an American staple: Italian-style syrups are added to a freshly brewed caffè latte, making it a hazelnut latte, a raspberry latte, and on into the multiflavored latte sunset. Several brands of flavored syrup, made in both the United States and Europe, now compete with the widely distributed Torani line. The all-natural Monin line has a reputation for subtlety, the Torani for energetic directness. If you try one of these syrups at home, keep in mind that they sweeten as well as flavor. If you are a sweet-loving sugar avoider, try one of the sugar-free syrups put out by DaVinci and others. DaVinci also offers all-natural-ingredients syrups. Currently the most popular flavors for coffee drinks are vanilla, hazelnut, Irish creme, and amaretto. If you have trouble finding syrups retail, consult Sources.

Serving Receptacles and other Accessories

Each of the traditional espresso drinks has a preferred serving receptacle. They are specified later in this chapter in the descriptions of the various drinks.

In Italy, espresso is almost never dispensed into plastic foam or cardboard. Such materials kill the delicate perfume of straight espresso. Rather than carrying their coffee back to work with them, Italians usually down a quick one standing at the bar, then fire off to work from there. This practice reflects the “small, powerful, perfect” aesthetic of Italian espresso cuisine.

Elegantly clad waiters and gofers can be seen hurrying through the business districts of large Italian cities carrying espresso drinks on trays, but these drinks are almost always dispensed into miniature insulated cups provided by the business person who is about to receive the coffee from his or her favorite bar. These little covered, insulated cups are usually made of metal, and are refined expressions of the designer’s art.

Classic, heavy demitasse and cappuccino cups and matching saucers, together with the tall, 16-ounce glasses used in most North American caffès for caffè latte, can be found at near wholesale prices in restaurant supply stores. Such places also carry inexpensive demitasse spoons and long “iced tea” spoons to match the tall caffè latte glasses. More expensive, more distinctive, and often more fragile versions of these specialized receptacles and utensils are sold in kitchenware and specialty coffee stores, catalogs, and websites. Some sellers also may carry glass or ceramic bowls reminiscent of those used to serve caffè latte in Italian-American caffès during earlier decades.

Small to medium-sized stainless steel pitchers appropriate for frothing milk are useful but not essential. (You can froth milk in a large ceramic mug, for example.) A good frothing pitcher is light in weight, open at the top, with a broad pouring lip to facilitate coaxing frothed milk from pitcher to cup. If you buy such a pitcher, make certain that it fits easily under the steam wand of your espresso brewer.

Thermometers that clip on the side of frothing pitchers to assist in monitoring the exact heat of the milk under the froth are useful for beginners. I discuss these devices in more detail here.

Knock-out boxes like those used by small restaurants and caffès to bang the spent grounds out of the filter in preparation for the next dose of coffee may be useful for those who entertain a good deal or who wish to professionalize their espresso habit. A waste container with a solid edge works almost as well, but isn’t nearly as elegant.

A jigger, or bartenders’ shot glass marked at 1¼ ounces, is useful when brewing with pump and piston machines. Since the connoisseur’s single serving of espresso should not exceed 1¼ ounces, the shot glass keeps you honest. And if you want to cut your serving short at an ounce or less, the transparent glass with measuring mark also facilitates that act of aesthetic restraint. When working at the more baroque end of espresso practice, use these glasses to measure syrups for flavored caffè lattes and similar extravagances.

Tampers, the little devices used to level and compress ground coffee in the filters of pump and piston machines, always come with the machines, but some aficionados become as involved with their tampers as cooks become with their knives, and buy fancy tampers made of metal and precious wood.

All such equipment can be purchased at most larger specialty stores, including the ubiquitous Starbucks, and on the Internet. See Resources.

TRADITIONAL CUISINE AT HOME

Straight Espresso

If you are after the perfection of straight espresso at home, you need to purchase a small pump or manual lever machine (categories 3 or 4, here). Brewing devices that work by steam pressure alone, like those in category 2, here, will make authentic espresso drinks with milk, but at best produce a flavorful but thin-bodied imitation of the unadorned drink. A perfectly pressed espresso exits the filter holder in majestic deliberation, all heavy golden froth that only gradually condenses into a dark, rich liquid as it gathers in the cup. Such results can only be gotten with good technique on machines that exert more than the relatively feeble pressure generated by the steam-only devices in categories 1 and 2.

Once you have mastered the brewing routine (see here), the next step in making straight espresso the way you like it is to experiment with blend and roast (see Chapter 6). If your espresso tastes too sharp, try lighter-roast blends of sweeter coffees until you find one that suits you. If your espresso lacks punch try and a darker-roast blend. If you crave still more sharpness try a dark blend of higher-grown coffees like Guatemalas, Costa Ricas, or Kenyas.

Sweeteners and Flavorings. Don’t feel reluctant to add sugar to straighten espresso for reasons of sophistication, by the way. Italians almost universally sweeten espresso, and the prejudice against adding sugar to coffee is one of those Puritan tics peculiar to some North Americans.

Some of the finest espresso blends are so naturally sweet (particularly those based on the finest Brazil coffees) that they can be drunk quite comfortably black. In terms of taste, the best sweetener for straight espresso is probably raw or demerara sugars. Honey tends to lose its sweetness when added to coffee.

Crema. Crema, the golden froth that mists over the surface of a well-made straight espresso and the subject of mystical rhapsodies by Italian espresso lovers, can present a problem for home brewing aficionados. You can consistently achieve it only with the pump and piston machines in categories 3 and 4, here. If you own such a machine, and brew carefully, following the prescriptions here, your espresso should display the rich flavor and heavy body of the true product, together with at least some crema. If your espresso tastes good but you’re not getting enough crema to make you happy, consult the relevant Espresso Break, here, for some advice.

Receptacles. Straight espresso is traditionally served in a three-ounce cup (demitasse, French; tazzina, Italian), with appropriately proportioned spoon and saucer. To serve a single shot of espresso in anything except a small porcelain cup is like serving a fine wine in a jelly glass. Only a little less aesthetically disturbing is destroying the harmonic proportions of the espresso ensemble by serving a normal teaspoon on or next to the properly tiny cup and saucer. Everything about the Italian espresso ritual is focused on the satisfaction of a perfect moment that flawlessly fuses taste and gesture.

The tazzina must be warm when the coffee is pressed into it or the heavy cup will excessively cool the delicate coffee. Some home pump machines provide cup warming shelves, and with others the top of the machine can be used to keep cups warm regardless of the designers’ intention. Hot steam from the steam wand or a little hot water run from the brew head can also be used to warm cups.

Straight Espresso Variations

The normal serving size for a true aficionado’s espresso is about one-third to one-half the volume of a three-ounce demitasse, or 1¼ to 1½ ounces. Corto, short, or short pull means an espresso cut short at no more than one ounce. Lungo, long, or long pull refers to an espresso that almost completely fills the three-ounce demitasse. In both cases, the amount of ground coffee filling the filter basket should be the same; i.e. one dose, or about two level or one heaping tablespoons. The difference is the amount of water you allow to run through the coffee.

Espresso Romano is a normal serving of espresso with a twist of lemon on the side. You rub the outer surface of the lemon peel around the edge of the tiny cup so as to lightly and exquisitely scent the espresso as you drink it. The lemon paradoxically causes the espresso to taste sweeter, making the Romano a good choice for subtle, sugar-avoiding palates. Variations on the Romano replace the lemon peel with orange or tangerine.

Doppio or double espresso is simply two servings of espresso, brewed with two servings of ground coffee. The doppio, properly made, should fill only one-third to two-thirds of a 6-ounce cup with rich, creamy espresso. The suicidal triple espresso is simply a nearly full 6-ounce cup of espresso made with three servings of ground coffee. Since most home machines do not provide triple-sized filter baskets, those fools who might be tempted to drink a triple at home need to make it with two successive pulls.

For the Americano, essentially a North American–style, filter-strength coffee made by diluting a serving of espresso with several ounces of hot water, see the section on the new American cuisine below.

Assembling Simple Drinks with Frothed Milk

The distinctions among the various classic caffè drinks involving coffee and hot milk described here—cappuccino, latte macchiato, caffè latte, etc.—may seem a bit arbitrary. After all, the only actual differences are simple: the proportion of espresso to milk, the texture of the froth, how the milk and coffee are combined, and the kind of receptacle used.

However, I can vouch for the fact that these seemingly insignificant differences in procedure and presentation make for rather dramatic differences in taste among the various traditional drinks. So even though the distinctions among the various espresso-milk drinks may blur when you are making them at home, it is well to understand the gustatory goals behind these differences.

Here is a summary of the traditional coffee-milk drinks:

Espresso macchiato. Espresso “marked” with frothed milk. Adds the slightest topping of hot frothed milk to a tazzina of espresso. Here the espresso comes through in its full-bodied, sweetly pungent completeness; the milk barely mellows the bite of the coffee. An excellent way to take espresso for those who avoid sugar, but want the power of unadorned espresso. Good also after dinner, when a milkier drink like a cappuccino tastes too diffused and looks unsophisticated. Like straight espresso, served in a preheated 3-ounce demitasse.

Cappuccino. This is the prince (or princess) of espresso drinks made with milk. It is traditionally served in a 6-ounce cup, and the frothed milk is added to the coffee in the cup. The emphasis is on the froth rather than on the milk. A proper cappuccino is made with more milk than an espresso macchiato, but less than a latte macchiato, and considerably less than a caffè latte.

If a cappuccino is made correctly, the perfume and body of the espresso completely permeate the froth and milk, extending throughout the drink without losing a molecule of power, while the sharpness of the coffee is softened without being subdued. By comparison, the ubiquitous North American “latte” is milky, feeble, and insipid. However, few are the cappuccinos that are made correctly. Italian espresso blends are made to be drunk straight, so the Italian cappuccino is usually too bland. On the other hand, the North American cappuccino is usually bitter. The beans have been overroasted, the coffee overextracted, and the milk has been frothed too stiffly, so that it floats to the top of the espresso rather than subtly uniting with it.

Even made incorrectly, the cappuccino is a pleasant drink. But made correctly, it is an experience that turns ordinary coffee drinkers into obsessives, searching the world, or at least their neighborhoods, for a good cappuccino, and even reading entire books like this one to find the secret of how to assemble one at home.

Secrets of the Cappuccino. Here is how to produce an authentic cappuccino at home. Make a perfectly pressed, very rich, small quantity of espresso, 1 to 2 ounces, no more. Use a pump or piston machine if possible, and follow the instructions for pressing coffee here as precisely as possible. Use a good North American espresso blend, medium-dark brown but not blackish, with oil just beginning to appear on the surface of the bean. Press the coffee into a warm 6-ounce cup.

Froth the milk to the point that it is still dense and a bit soupy, full of many tiny bubbles rather than a relatively few large ones. It should barely peak if you move a spoon through it. It should not stand up puffily. It should be hot, but not scalding. See here for instructions on frothing milk.

Pour the frothed milk into the cup. If you have frothed the milk correctly, and if you are using a thin-edged metal pitcher, the milk and froth should move together into the cup. You may need to encourage the froth with a spoon, however. The milk should not (cannot if it is frothed correctly) stand up like meringue above the top edge of the cup. A visual mark that you have done everything correctly is a brilliant white oval or heart shape on the surface of the drink, surrounded on all sides by a ring of dark brown, created by the espresso crema that has been carried to the surface of the milk.

Obviously, such precision does not come with your first home cappuccino. But if you have some idea what you are trying to achieve, your very first attempts should taste better than the production of most North American caffès.

Latte macchiato. The opposite of espresso macchiato, in that the milk “marks” the espresso rather than espresso marking the milk. There is not a great difference between espresso macchiato and caffè latte. Certainly made at home the two drinks will tend to overlap. With the latte macchiato the espresso is poured into a medium-sized glass of hot milk. The emphasis is on the milk, not the foam, and the coffee, when dribbled into the glass, tends to stain the milk in gradations, all contrasting with the modest white head of froth. The latte macchiato is a breakfast or early-day drink. It is the Italian version of the North American caffè latte.

Obviously the better and richer the espresso, the better the latte macchiato, but crema is irrelevant, and you can get away with espresso that is flavorful but somewhat light-bodied, the kind you can achieve with the modest steam-pressure machines described in category 2, here. The sharp-flavored, oily, darkish roasts preferred by many North American caffès and roasters come into their own in the latte macchiato and caffè latte. The sharp flavor penetrates the milk better than the more rounded, sweeter roasts and blends that are appropriate for straight espresso.

The Italian macchiato is made with 1 to 2 ounces of well-brewed espresso, dribbled into about 5 ounces or so of hot milk, topped with froth in an 8-ounce glass. But the exact proportions hardly matter. The essential idea is hot milk, coffee, a little froth, and a tallish glass.

Caffè latte. The caffè latte dilutes the espresso in even more milk, in a taller glass or a bowl, with the espresso and milk poured simultaneously into the glass or bowl. The latte is definitely a breakfast drink. The essential idea is to provide something to dip your breakfast roll into and enough liquid to wash the roll down with afterward. As with the latte macchiato, the head of froth is usually modest, so as not to interfere with the roll-dipping operation and not to distract from the psychological sensation of virtually bathing in hot, milky liquid.

The North American latte usually combines one longish serving (about 1½ ounces) of espresso with enough milk to fill a 12- to 16-ounce glass. This recipe produces a weak, milky drink, and has encouraged various customizations involving less milk and more espresso. A terminology has evolved that permits the espresso bar customer to specify both number of servings of espresso (single, double, triple, or quad, or four) and volume of milk (small or short, or enough milk to fill an 8-ounce container; tall, enough to fill a 14-ounce container; or various pop terms like grande, 16 ounces, venti (Starbucks), or mondo, enough to fill 20 to 24 ounces). Thus a latte can range from a powerful drink with three servings of espresso and only a few ounces of milk to a drink in which a single serving of espresso barely flavors a virtual kindergarten class’s worth of hot milk.

Obviously all of this terminology has little application to assembling a caffè latte at home. You experiment with the proportions of milk to coffee until you arrive at a satisfying balance. Most people customize the proportions to suit the moment: They may crave a stronger or a weaker drink depending on the time of day and the current state of their nervous systems and work schedule.

The standard receptacle in the United States for the caffè latte is the plain, 16-ounce tapered restaurant glass used in other contexts for serving everything from milkshakes to beer. A more interesting and, arguably more authentic, serving receptacle for the caffè latte is a relatively deep 12- to 16-ounce ceramic or glass bowl.

Traditional Caffè Mocha

Next to the cappuccino, the caffè mocha is probably the most abused drink in the traditional espresso cuisine. The classic Italian-American caffè mocha combines an American-sized serving (1 to 2 ounces) of espresso and perhaps 2 ounces of strong, usually unsweetneed hot chocolate in a tallish 8-ounce ceramic mug, topped with hot milk and froth. The drink is sweetened to taste after it has been assembled and served, just as with any other espresso beverage. This drink, smoothly perfumy and powerful, has been turned into a sort of hot milkshake by most North American caffès. Operators essentially make a caffè latte with a dollop of chocolate fountain syrup in it. With a true mocha the chocolate flavor is true, deep, and strong; it permeates the froth and roars down your throat playing a sort of tantalizing tag with the taste of the equally powerful espresso.

The only trick to making the counterfeit caffè mocha at home is combining the chocolate syrup with the espresso before you pour in the milk. Use any good chocolate fountain syrup and adjust the volume of syrup and milk to taste. Those who are interested in experimenting with the classic caffè mocha will need to make a chocolate concentrate. One part unsweetened, dark chocolate powder mixed with two parts hot water makes an authentic version of this concentrate. The powder and water can be combined while heating them with the steam wand of the espresso machine. As you direct the steam into the water and chocolate, stir with a spoon or small whisk, working the floating gobs of dry chocolate down into the gradually heating water. Either sweeten the mixture to taste when you mix it (try brown or demerara sugar), or leave it unsweetened, giving you and your guests an opportunity to sweeten the assembled drink after it has been served. If you prefer a lighter-tasting concentrate, add a few drops of vanilla extract to the mix while you are heating it. Try about ¼ teaspoon to every cup of chocolate powder, adjusting to taste.

To make the classic caffè mocha, combine about 2 ounces of this concentrate with one serving (1¼ ounces) of espresso and enough hot, frothed milk to fill an 8- to 10-ounce mug. Vary the proportions of chocolate, espresso, milk, and froth to taste.

Once mixed, by the way, the chocolate concentrate can be stored in a capped jar in the refrigerator for up to three weeks. The mixture may separate; when you are ready to use the concentrate, invert and shake the jar, then pour out into a frothing pitcher or mug as much concentrate as you wish to consume, and reheat it, using the steam wand.

Some caffès now use a white-chocolate concentrate to produce special espresso drinks with names like White-Chocolate Mocha, Mocha Bianca, etc. To make an authentic white-chocolate concentrate melt in a double boiler approximately 2 ounces sweetened white baking chocolate in ½ cup boiling water. Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce heat to a low bubbling boil for about 3 minutes, stirring regularly. This concentrate also can be refrigerated for up to three weeks. Substitute it for the chocolate concentrate in caffè mocha and other chocolate-espresso-frothed milk drinks. It contributes a sweet, delicately flavored chocolate component to the drink. Torani and DaVinci both produce a pre-made white chocolate syrup that can be ordered through their respective websites. See Sources.

Both of the made-from-scratch chocolate concentrates can be used to make hot chocolate drinks without espresso. Simply combine the concentrate to taste with hot frothed milk.

POSTMODERN CUISINE AT HOME

Contemporary American cuisine brings an exuberant sense of experiment to espresso tradition. Most of its innovations can be duplicated easily at home.

Adding Flavors

The ingredients section leading off this chapter describes the various classes of flavorings in the new North American espresso cuisine. Making use of these flavorings at home could not be simpler: merely add Italian-style fountain syrup to taste or as indicated below to your favorite drink. See here for more on choosing syrups and Sources for suggestions on where to buy them.

Here are some suggestions for specific drinks.

Flavored Caffè Latte. If you make your caffè latte in a 12-ounce glass, start with ½ to 1 ounce of syrup to one serving (1¼ ounces) of espresso and about 8 ounces of hot frothed milk. Put the syrup in the glass, add the freshly pulled espresso, mix the espresso and syrup lightly, then add the frothed milk. Adding the syrup last, after the milk, tends to dull the drink. Nut flavors (amaretto, orgeat/almond, hazelnut) and spice (vanilla, anisette, crème de menthe, chocolate mint) are good places to start with your syrup experiments. Berry flavors are attractive, but most tropical fruit and soda fountain flavors (root beer, etc.) seem not to resonate well with coffee.

Flavored Cappuccino. Go very lightly with the syrup here, ¼ to ½ ounce at the most, or you may ruin the balance of the drink. Make a classic cappuccino (see here). Add the syrup to the espresso, mix lightly, and add the milk. If you enjoy visual drama, try applying a thin, moving dribble of syrup across the surface of the froth, creating an attractive pattern (or creatively messing up the counter).

Flavored Caffè Mocha. Make a classic mocha (see here), adding a dash of hazelnut, almond, orange, or mint syrup mixed in with the chocolate syrup.

For still further extravagances, see the section on Soda Fountain Espresso at Home: Hot Drinks (here), and Cold Drinks (here).

Garnishes: The traditional garnishes (unsweetened chocolate, cinnamon, grated nutmeg, and grated orange peel) are now augmented by an array of sweetened and unsweetened garnishing powders put out by various firms and marketed in fancy food and specialty coffee stores. See here. If you combine one flavor of syrup and another of garnish you have an opportunity to either subtly delight the palate or grossly confuse it. Flavor combinations that seem to marry well with espresso are orange and chocolate, almond and chocolate, hazelnut and chocolate, mint and chocolate, and orange and vanilla. Make the syrup one choice and the garnish the other. Specialty coffee stores usually sell the classic garnishes, and others can be found in the spice section of large supermarkets.

Coffeeless Espresso Cuisine

So long as you have the machine, the garnishes, the milk and the syrups, you might consider some espresso cuisine without the espresso.

Flavored Frothed Milk. This drink appears in caffès under a variety of names, from the no-nonsense “Steamer” to the fanciful “Moo.” Add frothed milk to syrup (start with ½ to 1 ounces syrup per 8 ounces milk) and mix.

Hot Chocolate, Cioccolata. Make a chocolate concentrate (see here), and top 3 to 4 ounces of hot concentrate with 4 to 5 ounces of hot frothed milk to fill an 8-ounce mug. Garnish with either chocolate powder, vanilla powder, grated orange peel, or shave white chocolate. Or simply stir chocolate fountain syrup to taste into milk while frothing it.

Hot Chocolate with Whipped Cream, Cioccolata con Panna. Halve the milk in the previous recipe and top with whipped cream, either unsweetened, sweetened, or flavored (for flavoring whipped cream see below).

Soda Fountain Espresso at Home: Hot Drinks

Once you have mastered the basic exclamatory vocabulary of syrups, frothed milk, espresso, and garnishes, you may want to add whipped cream to your repertoire. Add moderately stiff whipped cream (sweetened or unsweetened) to any espresso drink in place of a roughly similar volume of frothed milk. In other words, if you make a caffè mocha, omit about 2 ounces of frothed milk and replace it with a healthy dollop of whipped dream to fill the mug. Garnish the whipped cream as you would the frothed milk.

The Torani syrups company suggests flavored whipped cream. Blend 1 pint whipping cream with 3 to 4 ounces syrup. Store this sweetened, flavored whipped cream and use it as suggested above. Thus, if you’re careful and don’t get too dizzy with your choice of flavors, you can serve a caffè latte with milk and coffee augmented by one flavor and whipped cream by a second. And, of course, a dash of garnish to the whipped cream will complicate the business still further.

Try, for example, orange-flavored whipped cream on a classic caffè mocha; or simply vanilla-flavored whipped cream on straight espresso, with a garnish of chocolate powder. I won’t tempt the ghost of espresso purists past with anything more complex than those rather modest suggestions—experiment. Maraschino whipped cream on a passion fruit–flavored cappuccino, garnished with orange peel? I hear Signor Gaggia rolling around from here.

Hybrid Drinks

Caffè Americano. The Americano is another innovation apparently developed in Seattle. It permits you to produce something resembling North American–style filter coffee on an espresso machine. The trick is to make a single 1-to-2-ounce serving of espresso, then add hot water to taste. If you simply run several ounces of hot water through a single dose of ground coffee, you will end up destroying the subtle aromatics of the espresso with the harsh-tasting chemicals that continue to be extracted from the coffee after it has given up its flavor oils. If, on the other hand, you make a 6-ounce cup of coffee with three doses of coffee you are simply delivering a triple espresso, rather than an Americano, which tries to keep the perfumes of the original espresso while extending them into a longer drink with hot water.

For those who like the fresh aromatics of espresso, but also crave the lightness and length of an North American–style filter coffee, the Americano, made correctly, is an excellent compromise. You can brew medium-roasted varietal coffees as well as dark-roasted coffees using the Americano method, and some Seattle caffès and carts do exactly that. They will brew an Ethiopia Harrar Americano, a Sumatra Americano, etc.

Depth Charge. Appropriately named for the sneaky underwater munitions famous in World War II for destroying submarines, this caffeine-underground invention drops a serving of espresso (tastes best made short, about 1 ounce) into a cup of regular drip coffee. Caffeine overload aside, this can be a very pleasant and complex drink, particularly when the drip coffee is freshly brewed (try a brightly floral coffee like an Ethiopia Yirgacheffe).

Iced Espresso Drinks

You can make almost any espresso drink iced. There are several principles to be observed in converting hot drink recipes to cold, however.

• Use cold milk rather than hot milk in iced cappuccino, caffè latte, etc., so as not to melt the ice prematurely, thus overly diluting the coffee. If you wish to provide a decorative head of froth to dress up the drink and provide a setting for garnishes, add a modest topping of hot froth (not milk) after you have combined the ice, coffee, and cold milk. Or use one of the pumping French-press milk-frothing devices described here that produce a cold froth to start with.

• Espresso that has been brewed and then refrigerated will not make as flavorful a drink as freshly brewed hot espresso, but holds its strength better when poured over the ice. Take your choice.

• The home-mixed chocolate concentrate I recommend for the hot caffè mocha tends to separate in iced drinks. You may find a pre-mixed fountain syrup more satisfactory for a cold summer caffè mocha.

Latte Granita, Granita Latte, Frappuccino (Starbucks), Etc. Unlike straightforward iced espresso drinks, which are cold versions of the classic cuisine and sweetened to taste after serving, these are the slushy, sweet, partly frozen drinks served in caffès and espresso bars.

Caffès produce these drinks in one of two ways. The authentic approach involves combining freshly brewed espresso, milk, ice, sugar and (usually) vanilla in a high-powered commercial blender. This is the approach taken at Starbucks, Peet’s, and many other quality-oriented chains and caffès. The less authentic approach combines pre-brewed espresso (or even a commercial espresso concentrate) with the other ingredients in machines that maintain the mixture at freezing temperature while agitating it to prevent it from solidifying.

In both cases the result is a pleasantly grainy beverage: sweet, milky, and refreshing, though sometimes cloying if the barista overdoes the sugar. The advantage to the blender approach is the freshly brewed coffee, plus the possibility of customizing the drink by request.

It is difficult to make a drink with quite the heavy, smooth yet grainy texture of the commercial latte granita using a home blender, but you can produce a very attractive drink, better flavored than most caffè productions, and tailored to suit your own tastes.

For each serving brew one serving (1¼ ounces) of full-strength espresso. While the espresso is still hot, dissolve in it 1 to 3 rounded teaspoons of sugar. One teaspoon produces an austere if seductive drink; three will probably satisfy those with a sweet tooth. Combine the sweetened espresso in a blender with about 2 ounces of cold milk and 3 ice cubes per serving (partly crushed), plus a few drops of vanilla extract. Blend until the ice is barely pulverized and still grainy; serve immediately. Experiment with the amount of milk, ice, espresso, sweetener, and vanilla until you obtain a custom balance that satisfies you. You can brew and sweeten the espresso in advance and store it in a stoppered jar in the refrigerator for convenience, although the longer you refrigerate it the slightly less flavorful your “latte granita” will be.

For a mocha granita dissolve ½ to 1 fluid ounce of chocolate fountain syrup in the freshly brewed espresso along with the sugar. Proceed as above. For every ½ ounce of chocolate syrup reduce the sugar by 1 teaspoon.

The Traditional Espresso Granita. The austerely rich, classic Italian-American granita, more a dessert than a beverage, has become difficult to find in the United States, having been upstaged by the more ingratiating latte granita.

The classic granita consists of straight espresso that has been frozen and crushed, then served in a sundae dish topped with whipped cream. When eating it you combine the powerful espresso ice and the whipped cream in judiciously balanced spoonfuls.

For those who wish to experiment with this disappearing delicacy at home: Brew two doses of full-strength espresso per serving, freeze in an ice cube tray, then crush thoroughly before serving in a smallish parfait or sundae dish. Top with lightly sweetened whipped cream dusted with chocolate powder.

Soda Fountain Espresso at Home: Cold Drinks

Espresso, cold milk, ice, flavored syrups, garnishes, ice cream, and whipped cream can be combined in a literally endless number of ways. Here are just a few suggestions.

Affogato. Pour one or two servings (the shorter the better) of espresso over vanilla ice cream. Either stop there and start eating, or top with whipped cream, flavored or unflavored, and garnish with grated chocolate, white or dark, chocolate powder, or grated orange peel.

Cappuccino and Ice Cream. Combine one serving (1¼ ounces) espresso with 4 ounces cold milk; lay in a scoop of vanilla, chocolate, or coffee ice cream. If you prefer, top with a dollop of whipped cream and a dash of garnish.

Espresso Fizz. Pour one serving (1¼ ounces) freshly brewed espresso in a tall 12-ounce glass; mix in sugar to taste (try 1 teaspoon); fill glass with ice and soda water. Serve without mixing so that the drama of the sugared espresso lurking at the bottom of the drink can be appreciated. Before drinking mix with an iced tea or soda spoon.

Espresso Egg Creme. Pour one serving (1¼ ounces) freshly brewed espresso in a tall 12-ounce glass; mix in sugar to taste (try 1 teaspoon). Add 1 ounce whole milk or half and half and fill glass with ice and soda water. Serve as in the previous recipe.

Mocha Egg Creme. Pour one serving (1¼ ounces) freshly brewed espresso in a tall 12-ounce glass; mix in ½ to 1 ounce commercial chocolate syrup. Add 1 ounce whole milk or half and half and fill glass with ice and soda water. Serve as in the previous recipes.

Italian Sodas. The syrups used in the contemporary American espresso cuisine were originally intended as soft-drink syrups. Combine 1 to 1½ ounces of one of these Italian-style syrups with ice and soda water to fill a tall 12-ounce glass. If you haven’t already, try orgeat (almond) or tamarind. Garnish the tamarind with a slice of lemon.

Italian Egg Creme. Pour 1 ounce whole milk or half and half and 1 to 1½ ounces syrup in the bottom of a tall 12-ounce glass. Fill with ice and soda water.

Espresso Float. Make an espresso fizz or espresso egg creme with chilled soda water but without the ice; leave space at the top of a 12- or 16-ounce glass; add 1 or 2 scoops of any flavor ice cream.

Espresso Ice Cream Soda. Make an espresso float in a 16-ounce glass, leaving room at the top for whipped cream, flavored or unflavored, garnished with grated chocolate or orange peel.

CHAI, OR THE ESPRESSO MACHINE MEETS TEA

Traditionally, chai is a mixture of spices and black tea drunk with hot milk and honey in the Middle East, India, and Central Asia. The spice mix is usually boiled for fifteen or twenty minutes and combined with black tea brewed in the usual way. This liquid concentrate is then strained and mixed with hot milk and honey.

Some innovator in the American Northwest came up with the notion of making the milk component of traditional chai hot frothed milk. People in Oregon loved it, some of them anyhow. People in Washington and California loved it. Chai is now part of the repertoire of the new American espresso cuisine, usually as a tall, hot milk drink called a chai latte. The traditional black tea chai has been joined by various non-caffeinated herbal tea chais, usually mint-based.

The spices in traditional chai always include ginger, cinnamon, and cardamom, but may include smaller amounts of coriander, nutmeg, cloves, star anise, fennel, black pepper, and orange zest. Americans are wont to add vanilla to sweeten and mellow the mix, but vanilla is not a typical component in authentic chais. As the chai phenomena spreads it also attracts the kind of dubious culinary innovation that brought us instant coffee and white bread. Chai mixes are becoming easier and easier to use and tackier and tackier in taste. The latest powdered versions resemble a sort of Middle Eastern Kool-Aid.

The espresso machine owner interested in making chai at home has several alternatives. I present them in order from most authentic to least.

Most Authentic Chai. (Short of grinding the spices yourself.) From a natural foods store buy a dry chai mix that keeps the spice mix separate from the tea (Marsala Chai is a good one) and prepare a liquid chai concentrate as described on the package. This involves boiling the spices (usually for about 20 minutes), removing the spice mix from the heat, adding black tea, steeping the tea in the spice mix for about 4 minutes, then straining the mixture. The resulting concentrate can be refrigerated for 2 to 3 weeks.

When you are ready for your chai latte, combine equal parts of frothed milk and the liquid chai concentrate. If you have refrigerated the chai concentrate, gently reheat it with the steam wand before combining it with the hot frothed milk. Sweeten with honey to taste. If in doubt start with 1 drippy, overflowing teaspoonful of honey per 6 to 8 ounces of the milk and chai combination.

Next Most Authentic Chai. Buy a chai mix from the refrigerator section of large natural foods stores. These chais are usually produced using the same procedure you would use at home, but often are sweetened with sugar syrup, which robs your chai of the authentic richness of the honey. Heat gently with the steam wand and mix as directed on the label with hot frothed milk.

Third Most Authentic Chai. Buy a liquid chai mix from the tea or coffee section of large natural foods stores. These chais, which do not require refrigeration, are liquid concentrates of varying degrees of authenticity using varying recipes. Most are sweetened with sugar syrup, some are not. Some include vanilla, some don’t. You can only experiment.

Least Authentic Chai. I am not sure whether powdered instant chai mixes (just add hot milk and serve!) have made it to specialty foods shelves, but if they have, walk on by. Every one I have tasted is listless, sugary, and cloying.

ESPRESSO SERVICE AT HOME

Espresso cuisine has become so various in its manifestations that any group of guests is likely to include a mix of purists, Seattle-style postmodernists, and espresso innocents. Consequently, those readers who entertain in conventional fashion may wish to serve their espresso cuisine buffet style and allow their guests to doctor their espresso themselves. The garnishes, unsweetened flavorings, and Italian syrups described earlier in this chapter all have a long shelf life. The syrups in particular are attractively packaged, and look colorful in an array on a tray or buffet.

The do-it-yourself approach also can be extended to assembling the traditional milk and espresso drinks. Serve a largish pitcher of hot frothed milk, a smaller pitcher of fresh espresso, and perhaps a pitcher of freshly mixed Italian-style hot chocolate, unsweetened, with sugar on the side, and let your guests have their will with it all. Purists, of course, will justifiably want their demitasse of espresso or their cappuccino brewed into the cup and served fresh, but those latte lovers who order a double mint mocha or whatever will doubtless be happier wading in themselves.

ESPRESSO DRINKS FORTIFIED WITH SPIRITS

Although there are many traditional recipes that combine spirits with drip or filter coffee, by comparison there is little precedent for drinks that marry espresso with alcohol. Perhaps the concentrated nature of espresso discourages such experiments. With the addition of flavored caffè lattes and latte granitas to the cuisine, North American espresso culture seems to be drifting more toward soda fountain than saloon. This trend may be owing partly to coffee and tea’s privileged position (along with red wine perhaps) as the only widely consumed intoxicants that have so far made it through the gauntlet of modern medical testing without being definitely implicated in any diseases. Perhaps by dissociating espresso from hard liquor, today’s coffee culture is attempting to consolidate its position as the “nice vice” of the millennium.

Nevertheless, those adults whose vices remain nice but also versatile will find that spirits and liqueurs used with discretion make an attractive complement to espresso.

Espresso fortified with grappa is probably the most classic such combination. Italians sometimes call it caffè corretto. Any espresso drink can be lightly fortified with brandy, which complicates both the flavor and effect of the drink without overwhelming its essential nature. Dark rum, anise-flavored spirits like Pernot and ouzo, and bourbon whiskey also combine attractively with espresso. Many people add a tiny dollop of sweet liqueur to straight espresso after dinner in place of the usual sugar, thus both sweetening and flavoring the cup. In fact, some enthusiasts do a sort of coffee overload by making the liqueur a dark-roast, coffee-based liqueur like Kahlua. This combination (or intensification) of coffee on coffee is a bit much to my taste, but those who find that the palace of culinary wisdom lies along the road of excess may enjoy it.

Of course the purist will protest that one shouldn’t mix good brandy or liqueur and good espresso, but should enjoy them separately, side by side. In a culture where caffè latte is flavored with chocolate mint syrup such objections seem a bit hypothetical.

Recipes for Fortified Espresso Drinks

Here are a few recipes that straightforwardly combine spirits and espresso, or at least make use of the unique capabilities of the espresso machine. Aside from the San Francisco cappuccino, they are all my own inventions, and usually represent traditional coffee-and-spirits recipes reinterpreted for the espresso cuisine.

San Francisco cappuccino is a traditional, yet curiously named drink, since it uses no espresso at all, but is a combination of hot chocolate, brandy, and frothed milk. Once a favorite of Italian-Americans and their bohemian associates in San Francisco, it has now virtually disappeared except at some old-time San Francisco bars like the wonderful Tosca in the North Beach neighborhood, where these brandy-chocolate drinks are still assembled using a pair of sixty-year-old Victoria Arduino espresso machines.

To create the San Francisco cappuccino at home, start by dissolving about 1 rounded teaspoon of unsweetened cocoa together with sugar to taste (1 rounded teaspoonful is traditional) in ½ ounce or so of hot water in a 6-ounce, stemmed glass of the heavy, flared variety designed for Irish coffee. You can use the steam wand of your espresso brewer to heat the combination as you mix it. Add 1 jigger (1½ ounces) of brandy, mix, and top with about 3 ounces of hot, soupily frothed milk, or enough to fill the glass. If you are dubious about the sugar part of the drink you can assemble the drink without sweetening it, and add sugar or other sweetener to taste after assembling the drink.

For Espresso Gloria (my name for a drink based on the traditional recipe for Coffee Gloria) combine 1 serving (1¼ ounces) of freshly-brewed espresso, about 3 ounces of hot water, 1 jigger of brandy, and granulated or brown sugar to taste (1 teaspoonful is traditional). Follow the same recipe, substituting Calvados, or apple brandy, for the grape brandy, and this drink becomes Espresso Normandy. To make it taste even more like northern France, use a darker-roast coffee than usual (the nearly black style that is usually sold as Dark French) when brewing the espresso.

Many traditional coffee drinks add a head of lightly whipped cream to sweetened, fortified coffee. A good variation on the whipped cream, spirits, and coffee theme for the espresso lover might be called Venetian Espresso, after the similarly named and constructed traditional drink, Venetian Coffee.

For Venetian Espresso place sugar to taste (1 rounded teaspoonful is traditional) in a 6-ounce, stemmed glass of the heavy, flared variety designed for Irish coffee. Brew one medium-to-long serving (1½ to 2 ounces) of espresso per glass, and pour over the sugar. Add 1 jigger of brandy and stir. Top with whipping cream that has been beaten until it is partly stiff, but still pours. The whipping cream should be soft enough to float with an even line on the surface of the coffee, rather than bob around in lumps. If the cream tends to sink or mix with the coffee, pour it into a teaspoon held just at the surface of the coffee. Once the whipped cream has been added this drink should not be stirred. Sip the hot coffee and brandy through the cool whipped cream. Made with crème de cacao this drink could plausibly be called Espresso Cacao. Other spirits also work well: bourbon, rum, Strega, Calvados, grappa, and almost any liqueur, including (for espresso overload lovers) dark-roast coffee liqueurs like Kahlua.

Espresso Brûlot Diabolique, Espresso Brûlot, Espresso Diable, and Espresso Flambè are all plausible names for a theatrical drink in which a flavored brandy mixture is heated, ignited, and combined with espresso. For each cup assemble one serving (1¼ ounces) of freshly brewed espresso, about 2 ounces of hot water, 1½ jiggers of brandy, granulated or brown sugar to taste (1 teaspoonful per cup is traditional), 1 large strip orange peel, 1 small strip lemon peel, and 8 whole cloves.

Warm the sugar, brandy, cloves, and orange and lemon peels in a chafing dish. Stir gently to dissolve the sugar. Place one serving espresso and 2 ounces hot water in each cup or glass, and place around the chafing dish. When the brandy mixture has been gently warmed (you should be able to smell the brandy very clearly from three feet away if it’s ready), pass a lighted match over the chafing dish. The brandy should ignite. If it doesn’t, it probably is not warm enough. Let the brandy burn for as long as you get a reaction from your audience (but not over half a minute), then ladle over the coffee. The flame will usually die when the brandy is ladled into the glasses. Don’t let the brandy burn too long, or the flame will consume all of the alcohol.

If you don’t have a chafing dish, put the sugar in each glass before you add the coffee; heat the brandy, cloves, and citrus on the stove. When the fumes are rising, pour into a fancy bowl and bring to the table. Carefully lay an ounce or two of the brandy mixture atop each glass of coffee; if you pour the brandy gently it will float on the surface of the coffee. To ignite the brandy, pass a match over each glass; to douse the flame, mix the brandy and coffee.

If you have trouble getting the brandy to float, try holding a teaspoon on the surface of the coffee and pouring the brandy mixture onto the spoon, letting it spread from there over the coffee. Also remember to add the sugar to the coffee, not to the brandy mixture, or the sugar will make the brandy too heavy to float.

The same drink is good made with dark rum. Follow the preceding instructions, substituting rum for brandy and omitting the flaming process. Another possibility is to use half rum and half brandy.

ESPRESSO BREAK

BREWING THE COFFEE

Note: The instructions that follow are meant to elaborate and complement those provided by the manufacturer of your espresso brewer. Be certain you have read and understood the safeguards, cautions, and instructions that accompany your brewing device before supplementing them with the advice and encouragement given below.

Coffee and Roast. Classic espresso is brewed using a coffee roasted medium-dark-to-dark brown, but not black. This roast usually is called espresso or Italian in stores, but any coffee roasted to that color, no matter what it’s called, will make a plausible espresso. Typically, however, blends designed especially for espresso blends make the best espresso beverages. They range from mild, sweet blends best for straight espresso, to dark, rich, pungent blends best for long milk drinks like caffè latte. See Chapter 6 and associated Espresso Break for more on choosing coffee for espresso brewing.

Always use at least as much coffee as is recommended by the manufacturer of your machine. Never use less. The usual measure for commercial machines is about two level tablespoons per serving. If in doubt, use two level tablespoons of finely ground coffee for every serving of espresso. In order to achieve a flavorful cup, you may have to use more. I find that with many home pump and piston machines a single serving of brewed espresso with the proper richness only can be obtained by using the double filter basket rather than the single, and by loading it with a double dose of ground coffee.

Brewing Principles. There are two requirements for making good espresso. First, you must grind the coffee just fine enough, and tamp it down in the filter basket just firmly and uniformly enough, so that the barrier of ground coffee resists the pressure of the hot water sufficiently to produce a slow dribble of dark, rich liquid. Second, you need to stop the dribble at just the right moment, before the oils in the coffee are exhausted and the dark, rich dribble turns into a tasteless brown torrent.

Grind. The best grind for espresso is very fine and gritty, but not a dusty powder. If you look at the ground coffee from a foot away, you should barely be able to distinguish the particles. If you rub some between your fingers, it should feel gritty. If you have whole beans ground at a store, ask for a fine grind for an espresso machine. A fine, precise, uniform grind is particularly important for pump and piston machines, which demand an especially dense layer of coffee to resist their high brewing pressure. See Chapter 7 and below for more on grind and grinders for espresso brewing.

Preheating Group, Filter holder, and Cup. Servings of straight espresso are so small and delicate that everything immediately surrounding the brewing act must be warmed in advance to preserve heat in the freshly-pressed coffee. If you have a pump or piston machine and are making your first cup, be sure to preheat the group, filter, and filter holder by running a small amount of hot brewing water through them. The demitasse into which you press the coffee should also be warm. Use the cup warmer on your machine, the top of your machine as an improvised cup warmer, or run some steam from the frothing wand into the cup. Those who drink their espresso with frothed milk can afford some carelessness in this regard. The hot milk usually manages to compensate lukewarm coffee and a cool cup.

Filling and Tamping. Different types of brewing devices have somewhat differing requirements for this important operation.

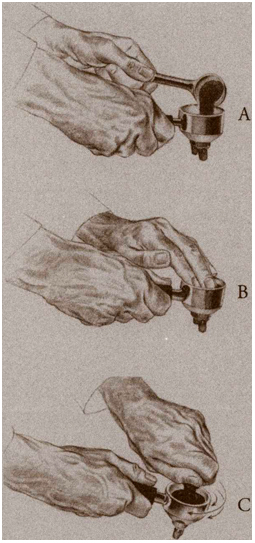

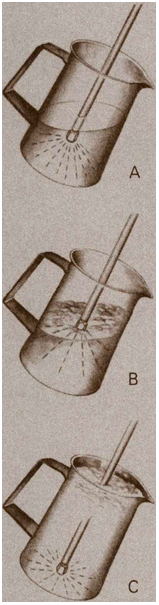

Filling and tamping for brewers and machines with external, caffè-style clamp-in filter and filter holder (categories 2 through 4): Fill the filter basket with coffee to the point indicated by the manufacturer, distributing it evenly in the filter basket (A). Then press the coffee down, exerting roughly similar pressure across the entire surface of the dose. With machines that work by steam pressure alone (category 2, here) use your fingertips to consistently but lightly press the coffee across its entire surface (B). Don’t hammer on it. With pump and piston machines (categories 3 and 4, here) use the device called a tamper that was packaged with your machine, and exert strong pressure, decisively packing the coffee into the filter basket (C). As you tamp the coffee you might simultaneously twist the tamper, which polishes the surface of the coffee and assists in creating a uniform resistance to the brewing water.

Never use less than the minimum volume of ground coffee recommended for the machine, even if you are brewing a single cup. If the coffee gushes out rather than dribbling, compensate by using a finer grind or by tamping the coffee more firmly. If it still gushes out, use a bit more coffee and, if you are grinding at home, increase the fineness of the grind. If the coffee oozes out rather than dribbling steadily, use a coarser grind or go easier on the tamping.

For pump and piston machines good brewing parameters can be described more precisely. Espresso from such high-powered machines tastes richest, sweetest, and most complete if each shot is limited in volume to one-and-one-half ounces and dribbles out of the filter holder in about 15 to 25 seconds after the first drop appears. If the shot gushes out in fewer than 15 seconds it is likely to be watery and thin tasting; more than 25 and it will taste burned and bitter.

A note on self-tamping machines and pods and capsules: Some pump machines have a self-tamping feature. The shower head on the underside of the group automatically compresses the coffee as you clamp the filter holder into the machine. You still need to use the tamper to assure that the coffee is evenly distributed in the filter basket, however. Machines that brew with pre-packaged, single-serving espresso pods or capsules require no loading or tamping. The pods or capsules are simply inserted into the special filter holder. With these machines you still must time the brewing accurately, however, to avoid ruining the espresso by running too much water through the ground coffee.

Filling and tamping for stovetop espresso brewers with internal filter baskets (most brewers in category 1, here): Most stovetop espresso brewers contain the ground coffee in a largish sleeve inside the device, rather than in a caffè-style filter unit that clamps to the outside. When using these stovetop devices with interior filter baskets, do not tamp the coffee unless the instructions that come with your machine ask you to do so. Use the same fine grind as recommended above, use as much as the manufacturer’s instructions recommend, distribute it evenly in the filter basket, and proceed. For stovetop machines with caffè-style filter holders that clamp to the outside of the machine, tamp lightly as described above.

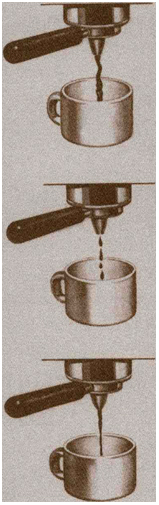

If the coffee is ground too coarsely or packed too loosely, the brewed coffee will gush out in a pale torrent, top. If ground too finely or packed too tightly, it will ooze out in dark, reluctant drops, center. If ground and packed correctly, it will issue out properly in a slow but steady, tapered dribble, bottom.

Clamping the Filter Holder into the Group. Always wipe off any grains of coffee that may have clung to the edges of the filter holder. They may cause brewing water to leak around the edges of filter and dilute the coffee. Also make certain that the filter holder is firmly and evenly locked into the group. Until you get the knack of the clamping gesture, you may need to stoop over and peer under the group to make certain that the filter holder is evenly snugged in place.

Brewing. Timing is everything is espresso brewing. The richest and most flavorful coffee issues out at the very beginning. As brewing continues, the coffee becomes progressively thinner and more bitter. Consequently, collect only as much coffee as you will actually serve. If you are brewing one serving, cut off the flow of coffee after one serving has dribbled out, even if you have two servings of ground coffee in the filter basket. If you are brewing two servings, cut off the flow after two. And no matter how many servings you are trying to make, never allow the coffee to bubble and gush into your serving carafe or cup. Such thin, overextracted coffee will taste so bad that it’s better to start over than to insult your palate or guests by serving it.

If you are using a pump or piston machine, each shot or serving of espresso should dribble out in about 15 to 20 seconds from the moment the first drop appears. However, gauge when to cut off the flow of coffee by sight, not by clock or timer. The fineness of the grind may vary, as will the pressure you apply when tamping. Consequently, the speed with which the hot water dribbles through the coffee will also vary from serving to serving. If in doubt, cut off the flow of coffee sooner rather than later. Better to experience a perfectly flavored small drink than an obnoxiously bitter large one. As you gauge the flow of coffee keep in mind that it will continue to run into the cup or receptacle for a moment or two after you have turned off the pump or shut off the coffee valve.

If you use a pump or piston machine, brewing into a jigger, or bartender’s shot glass, is a simple way of making certain that you do not produce overlong, bitter-tasting shots when you are brewing for frothed-milk drinks. For a classic 1¼-ounce serving, brew the shot, including crema, up to the line on the glass.

If you brewer does not have a mechanism for cutting off the flow of the coffee, you will need to improvise. If the design of the machine permits, use two separate coffee-collecting receptacles, one to catch the first rich dribbles, which you will drink, and a second to catch the pale remainder, which you will throw away. Whatever you do, don’t spoil the first bloom of coffee by mixing it with the pale, bitter dregs.

Knock-out and Cleaning. Pump and piston machines can be recharged with further doses of coffee while the machines are still hot. To remove spent grounds from a hot filter, turn the filter holder upside down and rap it smartly against the side of a sturdy waste container or against the crosspiece of the waste drawer that may have come with your system. This can be one of those pleasantly nonchalant gestures that perfects itself with time and practice. Aficionados may wish to professionalize by purchasing a small knock-out box of the kind used in small caffès. Wipe any leftover grounds off the edge of the filter holder and fill with the next dose of ground coffee. If significant amounts of spent coffee stick inside the filter you may need to rinse it before refilling.

A few machines may not incorporate a catch to retain the filter inside the holder. In this case you have no recourse, but to dig the grounds out with a spoon.

Regularly wipe off the gasket and shower head on the underside of the group. Spent coffee grains tend to cling there. Less often, pop the filter basket out of the filter holder, and wash both parts. Take note of the manufacturer’s instructions for decalcification. If you live in an area with particularly hard water, I would recommend using bottled water, particularly if you own a pump machine. The workings of these machines are especially vulnerable to calcium build-up.

ESPRESSO BREAK

THE CREMA QUESTION

Crema, the natural golden froth that graces the surface of a well-made tazzina of straight espresso, is an almost mystical obsession among Italian espresso lovers. Its only practical role is to help hold in some of the aroma until the coffee is drunk, but its cultural connotations are legion.

For Italian espresso professionals it is the key to diagnosing the coffee underneath. Dark-colored crema indicates a blend heavy with robusta coffees. Golden-colored crema reveals a blend based on higher-quality arabica coffees. Crema made up of a few, large bubbles indicates a coffee that has been brewed too quickly and is probably thin-bodied. Dense, clotted cream indicates a coffee that has been brewed too slowly and may be burned.

For the Italian bar operator crema is the mark of achievement: a perfect golden stream of froth descending majestically from the filter holder is a demonstration, endlessly repeated, of his mastery. For those Italians who simply like good espresso, cream is a visual prelude to the sensual pleasure of the coffee itself, promising sweetness rather than bitterness, rounded richness, rather than one-dimensional thinness.

Perhaps crema suggests even more. A tazzina of espresso without crema stares up with dark, disconcerting blankness, empty of promise, whereas a crema-covered cup seems veiled with intrigue and mystery. Crema intimates grace and elegance, abundance. By comparison a cremaless cup appears exposed and impoverished.

Crema and You

No doubt that last paragraph projects too much, but it is almost impossible to underestimate the role of crema in the mystique of straight espresso. The problem is, a cup of espresso can taste just as good without crema as with, and home espresso lovers may find themselves so intimidated by the quest for crema that they may deny themselves the pleasure of enjoying an otherwise good tazzina of cremaless espresso.

So, above all, if your espresso tastes good but has little crema, enjoy the coffee first and worry about how it looks later.

Given that advice, here are a few steps to take if you continue to be concerned about cremaless espresso.

Resign Yourself if You Are Using a Steam-Pressure-Only Brewer. If you are using a brewer that makes use of the pressure of trapped steam alone to press the brewing water through the coffee (categories 1 and 2, here), either give up on crema or buy a pump machine. Because, even if you follow the instructions for brewing here very carefully, you will generate only a little crema. Steam-pressure-only brewers will produce reasonably good espresso drinks with milk, but will not produce a straight espresso with the richness and body, or the crema, of the caffè product.

Good Technique. If you are using a pump or piston machine (categories 3 and 4, here), begin your pursuit of crema by reviewing your brewing technique against the instructions here. Make certain your grind is a fine grit, that you use sufficient coffee, that the coffee is evenly distributed in the filter, and that it has been tamped hard, with a twisting motion of the tamper, to polish the surface of the dose.

Precision Grind. Above all, review the grind of your coffee. It should be a very fine grit, but also a uniform grit, produced either by a large, commercial grinder in a store, or by a specialized home espresso grinder. See Chapter 7 for more on precision grind and how to get it.

Fresh Coffee. Make certain your coffee is fresh. If you buy whole bean coffee in bulk, buy it from a vendor who emphasizes freshness, keep it in a sealed container in a cool, dry place, and grind it as close to the moment of brewing as possible. If you use pre-ground, canned coffee, immediately transfer the excess coffee to a sealed container for storage.

Lots of Ground Coffee. This may qualify as cheating, but often the only way to achieve good crema on some pump machines is by using more than the recommended amount of coffee per serving. The normal recommended dose of ground coffee per shot of espresso is slightly less than 2 level tablespoons. For better crema use the double filter basket rather than the single and use at least half again as much coffee per serving, or about 3 level tablespoons.

Small, Pre-Warmed Cup. Brew directly into a narrow-sided, 3-ounce demitasse cup that has been pre-warmed. The warm, narrow cup will help build up and hold the crema.

Special Devices to Promote Crema. Some pump machines have special gadgets built into the filter holder to promote the formation of crema. All of those that I’ve tried help considerably. Unfortunately, you must buy the entire machine to get the gadget, so this solution is only appropriate for those so infatuated by crema that they are willing to purchase a new machine to get it.

Turn Buddhist. Decide that plainness and substance are more important than a little illusory froth.

ESPRESSO BREAK

FROTHING THE MILK

Most Americans prefer their espresso blended with hot, frothed milk. Fortunately, the majority of espresso-brewing appliances now sold in the United States have built-in steam apparatus suitable for frothing milk. If you like espresso drinks with milk, make certain that any espresso brewing device you purchase has such a mechanism.

If the clerk doesn’t know what you’re talking about, look for a small pipe, usually about ¼ inch in diameter and a few inches long, protruding from the side or front of the device. Some beginner-friendly machines may replace the conventional wand with an automatic milk frother (it looks like a small plastic cylinder protruding from the front of the machine) that sucks cold milk into one end and squirts out hot frothed milk at the other. These devices may sound wonderful, but in fact are fussy, demanding, and delicate. I would recommend against buying any machine that does not give you the option of replacing the automatic frother with a conventional steam wand.

Heating the milk with the steam wand is easy; producing a head of froth or foam is a little trickier, but like riding a bicycle or centering clay on a potter’s wheel, exquisitely simple once you’ve broken through and gotten the hang of it.

Another alternative for milk frothing is one of the little cylindrical stand-alone devices that look like French-press coffee makers. However, assuming you already have steam up for espresso brewing, it hardly seems worthwhile putting yourself through several additional steps to froth milk when you can do it in thirty seconds using the steam wand on your brewer.

At any rate, the instructions that follow assume you are faced with using a conventional steam wand on a conventional espresso maker. Advice for using the stand-alone frothers appears at the end of this section.

Steps in Making Drinks with Frothed Milk. There are three stages to making an espresso drink with frothead milk. The first is brewing the coffee; the second is frothing and heating the milk; the third is combining the two. Never froth the coffee and milk together, which would stale the fresh coffee and ruin the often eye-pleasing contrast between white foam and dark coffee. Nor is it a good idea, even if your machine permits it, to simultaneously brew espresso and froth the milk. Concentrate on the brewing operation first, taking care to produce only as much coffee as you need. Then stop the brewing and turn to the frothing operation.

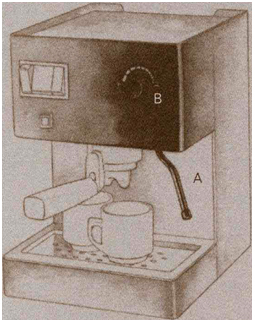

The Frothing Apparatus: The steam wand, also called steam stylus, pipe, or nozzle, is a little tube that protrudes from the top or side of the machine (A). At the tip of the wand are one to four little holes that project jets of steam downward or diagonally when the steam function is activated, or in some cases a special nozzle designed to facilitate the frothing operation. Nearby you will find the knob that controls the flow of steam (B). While you are brewing coffee, this knob and the valve it controls are kept screwed shut.

Some machines do not have a screw knob to control the flow of steam for frothing. Instead, you simply activate the steam function with a switch, automatically releasing what the manufacturer considers to be the optimum flow of steam for the frothing operation.

Still other machines come with aerating nozzles on the end of the steam wand designed to make the frothing operation easier. These devices suck additional room temperature air into the milk along with the steam, presumably helping to fluff up the milk. Most still require a conventional frothing technique as described below, however. They do not replace the traditional frothing procedure; they simply make it easier. However, one aerating nozzle, the Krups Perfect Froth, requires a completely different technique, which is described in the Krups literature. With virtually any other kind of steam nozzle or apparatus you will find the following instructions helpful, if not essential.

Do not feel deprived if your machine has a conventional or only mildly modified frothing apparatus, by the way. Anyone with the smallest amount of patience can master the normal frothing operation, and in the process gain considerably more control over the texture and dimension of the froth than is possible with the less conventional apparatus. And frothing milk the old-fashioned way may turn out to be one of those noble, Zen-like rituals that stubbornly resist progress, like manual shifting in sports cars, wooden bats in baseball, and catching fish with dry flies.

Frothing Pitchers and Milk Thermometers. Milk can be frothed in any relatively wide-mouthed container that fits under the steam wand of your machine. If you take your drink in a mug, for example, you can simply froth the milk in the same mug you use to consume your drink. However, small stainless steel pitchers designed specifically for milk frothing are useful. They are light in weight, and usually have a broad, rolled pouring lip, which facilitates moving the froth and milk together in one smooth motion from pitcher to cup.

Frothed-milk thermometers resemble meat thermometers, and clip on the edge of the frothing pitcher, with the dial facing up and the temperature probe extending down into the pitcher. These thermometers assist in monitoring the exact heat of the milk under the froth (135°F. if you plan to enjoy your drink immediately, up to 165° if there will be a delay in serving or drinking it), and help the novice avoid one of the most prevalent errors of milk frothing: overheating or scalding the milk. However, I find that simply feeling the bottom of the milk frothing container (when it’s too hot to touch, stop frothing) works just as well.

Three aerating nozzles designed to make milk-frothing easier. The removable Krups Perfect Froth device, top; the Braun Turbo Cappuccino, which incorporates a little spinning, fan-like element inside the nozzle, center; and the Saeco Cappuccino, bottom. The majority of espresso brewing devices sold in North America now incorporate such nozzles.

The Milk. Virtually any liquid dairy product, from skim milk to heavy cream, plus most imitation liquid dairy products such as soy milk, can be frothed using the steam apparatus of an espresso brewing device. More on choosing milk for espresso drinks is given in Chapter 9. Milk with more butterfat maybe slightly easier to froth for beginners than milk with less.

Transition between Brewing and Frothing. In less expensive, steam-pressure machines (category 2, here), and in piston machines (category 4, here) this transition is accomplished simply by closing the coffee-brewing valve or ending the coffee-brewing operation and opening the steam valve. In button-operated pump machines (category 4, here), there is usually a more complex transitional procedure, which will be described in the instructions accompanying your machine. The transition involves raising the temperature of the boiler where the water is heated from the somewhat lower temperature best for brewing to a higher temperature suitable for producing steam. You press a button or trigger a switch and wait twenty or thirty seconds for the boiler to achieve the higher temperature. In such machines it is particularly important to bleed the hot water from the steam pipe before beginning to froth milk, since a substantial residue of water usually collects in the pipe during brewing, which can dilute the milk. Place an empty frothing pitcher or cup under the steam wand and open the valve. Wait until all of the hot water has sputtered out of pipe and a steady hiss of steam is escaping the nozzle before beginning the frothing operation.

A Dry Run. Before attempting to froth milk for the first time, practice opening and closing the steam valve with the machine on, the brewing function off or closed, and the steam function activated. Get a general sense of how many turns it takes to create a explosive jet of steam, and how many to permit a steady, powerful jet. It is the latter intensity that you will use to froth milk: not so powerful that the jet produces an overpowering roar, but powerful enough to produce a strong, steady hiss.

Note that steam cools rapidly as it exits the nozzle of the wand. Even four inches from the nozzle the steam is merely wet to the touch (try it) and presents no danger of injury. Hot milk churning or spattering out of the pitcher during incorrect frothing can cause mild burns, however. Follow the instructions below carefully.

The Frothing Routine

• Fill the container or cup no more than halfway with cold milk (the colder the better; hot milk will not produce froth).

• Open the steam valve for a few seconds to bleed any hot water from inside the wand into an empty cup or container. Then close the valve until just a tiny bit of steam is escaping from the tip of the wand. This is to prevent milk from being sucked back up into the wand as you immerse it into the milk.

• Holding the container vertically, immerse the tip of the wand deeply into the milk (A). Slowly open the valve, then gradually close it until you get a strong, but not explosive, release of steam that moves the surface of the milk, but doesn’t wildly churn it.