6 BLENDS, ROASTS, AND ORIGINS

BUYING ESPRESSO COFFEE

Choosing a coffee is one of the delightful challenges of home espresso brewing. Although the subtlest of distinctions among single-origin coffees are lost in dark-roasting, the rich diversity of the espresso-suitable coffees now available presents the espresso drinker with a fascinating arena for experiment and connoisseurship.

CANS, PODS, BAGS, AND BULK

Coffees suitable for espresso brewing can be purchased in four forms: pre-ground in cans; as pre-ground, pre-packed single servings called “pods”; whole beans in cans and bags; and whole beans in bulk.

Buying whole beans in bags or bulk offers the espresso drinker by far the greatest number of blends and single-origin coffees from which to choose. For the true aficionado, there also is the alternative of buying coffee green and roasting it at home. Home roasters can assemble a veritable cellar of fine coffees, since in its green state coffee keeps rather well. Enough instruction to get started roasting at home is given here.

Pre-Ground, Canned Blends

Pre-ground coffees sold in supermarket cans are almost always blends. The only exception I’m aware of at this writing is a canned dark-roast Colombia.

Many of the most widely distributed canned dark-roast coffees are ground far too coarsely for home espresso brewing. If you are a novice trying home espresso brewing for the first time, do not start with a canned dark-roast coffee ground for all-purpose brewing. The coarse grind will only lead to watery, underextracted coffee and frustration. Several packaged dark-roast coffees are ground to espresso specifications, however. The labels of these true espresso coffees usually display language like “ground extra-fine for espresso brewing.”

In style, pre-ground, canned espresso blends range from mild, sweet styles prepared in northern Italy to reflect classic Italian taste, like the famous Illy Caffè, to much more darkly-roasted coffees with an earthy twist intended for “the Latin taste,” as the language on the can usually puts it, to a 100 percent Colombian with dry, acidy notes vibrating inside the bittersweetness of the dark-roast flavor. These canned, pre-ground coffees can provide a helpful orientation to the range of experience possible in espresso-style blends.

Nevertheless, canned coffees are limited in several respects. First of all, pre-ground coffees, regardless of packaging, simply cannot deliver a cup of espresso as fresh as can recently roasted whole-bean coffees ground immediately before brewing. Secondly, canned coffees can’t come close to offering the espresso aficionado the variety that whole-bean coffees do.

Espresso Pods

Pods are small, tea bag–like paper sacks of ground, blended espresso intended to fit into special filters provided with many pump espresso machines. They are typically packaged in single-serving foil envelopes. You open the envelope, pop the pod into the filter, and brew. The pod comes out of the filter as cleanly and simply as it went in.

Pods offer clear reassurance for the beginner because they are easy to use and guarantee a proper dose of properly ground coffee. However, they are very expensive, offer limited choice of coffee, and can only be used with pod-compatible pump machines (category 3, here). Furthermore, they create a good deal more waste packaging than whole-bean coffees.

Some pods are proprietary in format and designed to work with only one brand of machine, and vice versa. Increasingly, however, home pump machines are designed to give users the option of using either regular ground coffee or generic pods that work with any machine which follows something called the ESE (Easy Serving Espresso) standard. I strongly recommend that those interested in brewing with pods opt for maximum flexibility by buying one of the pod-optional, ESE generic-format machines rather than a machine that uses a proprietary pod format. Pod users almost always graduate to regular coffee when two points become apparent to them: first, brewing espresso is not so hard after all, and second, by using pods they are paying too much for less than fresh coffee.

Pods, like canned espresso coffees, are almost always blends. Like canned blends, pod blends usually come in a range of styles, from mild northern Italian styles to dark, pungent blends suitable for large milk drinks like caffè latte. Pods offer slightly more choice in coffee than do canned blends, but again, not nearly as much choice as whole bean.

Buying Whole-Bean Coffees for Espresso

Buying coffee as whole beans and grinding them just before brewing is by far the best alternative for espresso drinkers who are serious about quality. Buying whole-bean coffees and having them ground at the store is probably second-best.

Whole-bean coffees offer much more choice for espresso brewing, and produce (in most cases) a fresher, richer, more fragrant beverage.

Whole-bean coffees are sold in two forms: fresh in bulk from bins and in foil valve bags. The valve bags are designed to protect the coffee from both moisture and oxygen, the two sources of staling in coffee. The oxygen is usually flushed from the bags by using an inert gas like nitrogen before the freshly roasted coffee is dropped into the bag and the bag sealed. Freshly roasted coffee produces carbon dioxide, which is trapped inside the bag, further protecting the coffee from oxygen. The valve imbedded in the bag allows excess carbon dioxide to escape and prevents the bag from inflating.

Such bags most definitely do protect coffee from staling, but for how long? Not over a month, in my experience. But less responsible roasters and stores keep foil bags of coffee around for two, sometimes even three, months. One firm headquartered in Hawaii prints a “best by” date on the bottom of its bags one year from the roast date.

Furthermore, simply because a coffee is sold in bulk from a bin doesn’t mean it’s freshly roasted. Starbucks, for example, packages all of its bulk coffees in valve bags. Clerks simply open the bags and dump the coffee into the bins.

The bottom line? Freshly roasted coffee sold within a week of roasting is best. Freshly roasted coffee held in valve bags are a close second if the bags not held for more than three or four weeks.

Unfortunately, few retailers roast-date their coffee. They code the bags so that employees who stock the shelves know how old a coffee is, but customers don’t.

Ultimately, whether the coffee appears in bags or bins, it comes down to trusting your taste buds and trusting the store. Specialized coffee stores with high volumes are almost always more reliable sources than supermarkets. Stores with high volumes are typically more trustworthy than new stores with low volumes. Stores that roast on premises can be the best place of all to buy whole-bean coffees, assuming the roasting is done right. Locations of specialty coffee stores can usually be found in telephone classified pages under the retail coffee heading.

Stores of very large specialty coffee chains like Starbucks, Timothy’s World Coffee, Peet’s Coffee & Tea, and others offer a sort of compromise between locally run specialty stores and the supermarket. These companies may roast their coffee in very large quantities at centralized locations, but they put a laudable and largely successful emphasis on delivering fresh coffee. How the great-expanding-coffee-chain story will play out eventually in terms of freshness and quality remains to be seen.

Starbucks’ current excursion onto the shelves of supermarkets appears less laudable and less successful, at least in terms of delivering quality. My sampling suggests that the Starbucks supermarket line of coffees not only offers less choice than the more comprehensive line Starbucks sells in its own stores, but less character and distinction as well.

Those who find it inconvenient to shop for coffee may find ordering bulk coffee by Internet or telephone useful. Consult Sources. Coffees should be ordered through the mails only in whole-bean form. Unprotected ground coffees are likely to be half stale by the time they land on the porch. This means that you need a good grinder to enjoy mail-order coffee; consult Chapter 7 for details on espresso grinding and grinders.

SPECIALTY STORE DECISIONS

The range of coffees offered by specialty coffee stores and Internet sites can be daunting. The reader may want to skim through the Espresso Break on Coffee Speak here for an orientation to specialty coffee terminology.

For selecting among caffeine-free coffees by decaffeination method, see here; for buying coffees that respond to various environmental or social issues see here.

But once such concerns have been responded to, the subtler and perhaps more interesting decisions remain; what style of roast to buy; whether to buy a blended or unblended coffee; which blended or unblended coffee to buy; and finally, whether and how to assemble blends of your own.

Choosing a Roast Style

As indicated earlier, any style of roast can be prepared in an espresso machine and used to assemble espresso drinks, but only a medium-dark to dark-brown roast, darker than the typical North American roast but not black-brown, will produce the flavor we associate with espresso. See Chapter 4 for more on the process and philosophy of roasting. Coffees roasted toward the lighter end of the espresso spectrum retain some of the brisk, acidy tones characteristic of medium-roasted coffees; coffees roasted near the middle of the spectrum lose almost all acidy notes, replacing them with the pungent yet sweet flavor complex typical of darker-roast coffees; the very darkest roasts begin to lose body and display the monotoned, charred flavor typical of these nearly black styles.

The Complex Relationship of Roast and Coffee

Choosing espresso coffee by roast is complicated by the fact that most coffees intended for the espresso cuisine are blends, and the composition of the blend may either offset or reinforce taste tendencies created by style of roast. Generally, those roasters who prefer a mild, sweet espresso will pursue their objective on two fronts. They will use coffees with low acidity in their blends, and will also bring that blend of low-acidity coffees to a relatively light espresso roast to avoid provoking the bitter notes characteristic of darker roasts. On the other hand, those who prefer sharpness and punch in their espresso blends may use highly acidy coffees and bring those acidy blends to a relatively dark roast, thus emphasizing both acidity and the bitter side of the bittersweet dark-roast flavor equation. The effect of roast on coffee flavor can only be fully understood by roasting coffee oneself, or by finding a roaster who offers the same straight or unblended coffees in a variety of styles of roast.

BLENDED VS. UNBLENDED COFFEES IN ESPRESSO

Most of those who qualify as espresso experts argue for the superiority of blended espresso coffees over unblended. Their arguments often appear self-serving, however, since most experts are also in the business of selling coffee, and blends have several advantages for the coffee seller. First, they enable the seller to develop a loyalty to a certain blend, rather than loyalty to a more generic unblended single-origin coffee; second, they promote a mystification of the blending and roasting process, both of which are somewhat simpler than roasters make them out to be; and three, blends enable the more cost-conscious roaster to cut costs while maintaining quality.

Given all of that, good blends doubtless do produce a more satisfying espresso over the long haul, at least for those who prefer consistency over experiment and surprise. But for those who enjoy variety, unblended dark-roasted coffees themselves, plus the opportunity they afford for creating one’s own blends, offer an exciting opportunity for connoisseurship.

Espresso blends and blending are discussed in detail here. Once the issues and principles of espresso blending are understood, the next step is actually tasting a variety of blends. Espresso blends vary dramatically from roaster to roaster.

SINGLE-ORIGIN COFFEES IN ESPRESSO

Unblended, single-origin coffees consist of beans from one crop and one origin in one country. Most specialty stores carry a small selection of such unblended coffees brought to a dark roast suitable for espresso. They are usually identified by double- and triple-decker names like Dark-Roast Sumatra Mandheling, French-Roast Colombian Supremo, or Organic Guatemala Antigua Dark.

With some roasters, most notably the influential West Coast Peet’s Coffee chain, all coffees in the store are roasted dark, and consequently all can yield an interesting espresso. At this writing many roasters are imitating Peet’s extreme dark-roast style. Unfortunately, most of these dark-roasters-come-lately do not understand the style as well as the Peet’s roasters do, are too aggressive with the roast, and end up burning the beans. These dry, brittle beans produce a thin-bodied, bitter espresso. If you find a store in which all of the coffees are roasted dark-brown-bordering-on-black, try a half-pound as espresso, but don’t be surprised if the results are unsatisfactory and you need to go elsewhere for a coffee that produces a full, round, sweet beverage.

With coffee companies that don’t roast everything dark, the key terms identifying darker styles of roast appropriate for espresso are either obvious color words like dark or dark-roast; European geography names like Viennese, Italian, French; or (most explicitly) espresso. Any coffee preceded by these adjectives will make a plausible espresso, although those that are extremely dark, almost black, may produce a thin-bodied, bitter cup. For a summary of names for roast see the table. For more on coffee names generally see here.

Around the World in a Demitasse

For those interested in exploring single-origin coffees as espressos, here is an overview of the better-known coffees of the world from an espresso perspective.

Powerfully Acidy Coffees. The best-known are Kenyas, Strictly Hard Bean Costa Ricas and Guatemalas, Yemen mochas, and the better Colombias. These are all high-grown, dense-bean coffees that display bright, acidy notes in nut-brown roasts and turn intensely bittersweet in dark-brown styles. They may be a bit overwhelming as a straight espresso but will carry through almost any amount of milk and make excellent highlight coffees in espresso blends. Unlike Kenya and the Latin America coffees, Yemen coffees are dry-processed or dried inside the fruit, which may account for the way they often round out a darker roast better than many Kenyas or high-grown Central Americas. Straight Yemen brought to a moderately dark roast can make a superb espresso.

Classic Coffees with Gentler Profiles Most Caribbean coffees (Puerto Rico, Jamaica Blue Mountain, Dominican, Haiti, etc.), Mexicos, El Salvadors, Nicaraguas, Panamas, Perus, are wet-processed coffees with a bright but gentle acidity usually easily tamed by dark-roasting. The sweeter versions of these coffees will make a pleasant espresso, relatively light-bodied but round and lively. Some Perus produce a particularly agreeable demitasse.

Brazil Coffees. The finest Brazil coffees—low-acid, sweet, round, full-bodied—are espresso treasures. These coffees, which come into their own only when roasted and brewed as espresso, are grown on a handful of medium-to-large Brazilian farms, come from trees of the traditional Bourbon variety, and are dry-or “natural”-processed. They must be roasted tactfully to preserve their sweetness and will not tolerate extremely dark roast styles. But if everything is right these dry-processed Brazil Bourbons are among the most exquisite of espresso-inclined origins.

Hawaii Coffees. America’s obsession with its home-grown coffee leads me to give it its own category. Hawaii Kona, one of the world’s most expensive coffees, is hardly ever presented as espresso because its high-priced subtleties are lost in a darker roast. However, you will find Konas dark-roasted simply because the people who roast them don’t know any better. If you do try one of these inadvertently dark-roasted Konas as espresso, and if it hasn’t been destroyed in the roasting, it will yield a pleasant if light-bodied demitasse. On the other hand, some of the very best Konas are rather acidy coffees that make a powerful, bittersweet espresso along high-grown Costa Rica lines. Coffees from large farms outside the Kona district, on the islands of Kauai, Molokai, and Maui, are less expensive, available directly from the growers in dark-roast styles, and can make interesting espressos if the roast is handled carefully.

Indonesia and India Coffees. Coffees from the gigantic Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Sulawesi (old name Celebes) can make splendid espresso: full-bodied, sweet yet pungent, complex. The problem is finding good Sumatras and Sulawesis. Along with the rich, complex, sweet versions, many cheap, harsh-tasting Sumatras and Sulawesis find their way into North America. But there is no doubt that the best and sweetest rank with the finest dry-processed Brazils as the most desirable of espresso origins.

Wet-processed coffees from Java and Papua New Guinea produce sweet but lighter-bodied espressos than the best Sumatras and Sulawesis. India coffees are typically low-toned and display sweetness and body but may come off as a bit inert.

Ethopias and other African Coffees. Kenya coffees are in a class of their own: powerfully acidy, deeply resonant, alive with wine and (on occasion) berry notes, and wonderfully consistent. Typically, however, they are too acidy or (in a dark roast) too pungent for espresso brewing on their own. Ethiopia coffees tend to be fragrant, relatively light-bodied, and can make very interesting and elegantly nuanced espresso. The famous and distinctive Ethiopia Yirgacheffe, with its extraordinary floral perfumes, may be a touch too light-bodied for espresso, but can add wonderfully tantalizing high notes to a blend. Other African coffees, like Zimbabwes and Malawis, are wine- or fruit-toned coffees that make interesting but also relatively light-bodied espressos.

Robustas. The best coffees from the Coffea canephora or Robusta species imported into the United States are grown in the Ivory Coast, Thailand, and India. You will not find them for sale as single-origin coffees, however. If you are a home roaster and you manage to turn some up as green coffee and roast them, you will discover that they are heavy, flat, and inert. Some professional blenders condemn them. Others claim that they add resonance to an espresso blend, forming an unheard but amplifying sounding board for more assertive notes.

Aged and Monsooned Coffees. These specially handled coffees (see here) are usually too heavy and monotoned on their own, but in small quantities can add weight and complexity to blends.

A BLEND OF YOUR OWN

Having sampled some dark-roasted blends and unblended single-origins, readers may be interested in experimenting with their own blends. Most specialty stores will be happy to combine coffees for customers, providing the requests don’t become too complicated.

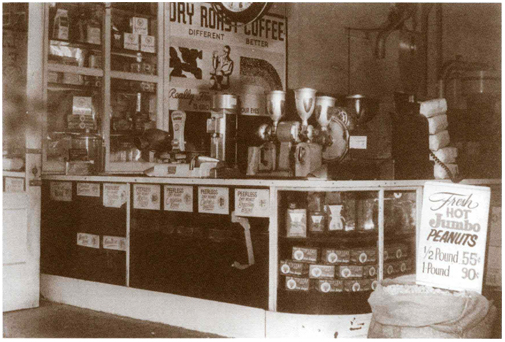

The open counter of the old Peerless Coffee Company in Oakland, California, an excellent example of the small storefront coffee-roasting establishments that were a familiar feature of North American shopping districts during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A few, like Peerless, survived to join the current revival of specialty coffee roasting. Peerless Coffee, still family-owned, now occupies a large plant a few blocks from its original home.

To create your own espresso blend, you might start with a base of dark-roast Brazil bourbons (dry-processed, often marketed as Brazil Bourbon Santos), Mexico, or Peru, then experiment by asking the clerk to add varying proportions of other beans. Twenty percent of an acidy, winy Africa coffee like Kenya plus perhaps another 20 percent of a pungently low-toned coffee like Sumatra or Sulawesi, both in either a dark or a medium-dark “full city” roast, combined with 60 percent dark-roast Brazil, Mexico, or Peru, make an interesting and lively blend. Experiment with the proportions of Sumatra and Kenya until you obtain a balance that satisfies you. Or try 10 percent Kenya and 20 percent Ethiopia Yirgacheffe, to add floral notes at the top of the profile as well as fruity mid-tones. For more ideas, look over the preceding section on Single-Origin Coffees in Espresso.

Those who are not all-out purists may enjoy adding small proportions of flavored beans to a personal espresso blend. Ten percent chocolate or hazelnut-flavored beans, for example, contribute an interesting flavor note, although the aftertaste may be cloying to an experienced palate.

ESPRESSO BREAK

COFFEE SPEAK: THE SPECIALTY COFFEE LEXICON

Variety, one of the attractions of specialty coffee, can also be one of its frustrations. Most specialty stores carry at least twenty different coffees; some may carry as many as fifty. The best Internet sites carry even more. The sheer babble of names and (in the case of the stores) the repetitive shades of brown in the bins can intimidate and confuse. Here are a few rules of thumb to assist in making sense of specialty coffee cacophony.

European Names. These usually describe blends of dark-roast coffee. Viennese, Italian, French, Neapolitan, Spanish, and European are all frequently used names for generic blends of coffee roasted darker than the (usually unnamed) American roast. Espresso and Continental are also popular names for generic dark roast blends. Most coffees described by these terms are suitable for espresso cuisine; choosing from among them is a matter of taste. See the Espresso Break for a complete list of roast names, and Chapter 4 for more on roasting and styles of roast.

Non-European Names. These usually describe unblended or single-origin coffees. Coffees sold in straight or unblended form, also called single-origin or varietal coffees, typically carry the name of the country in which they were grown: Kenya, Colombia, Costa Rica, etc. If these coffees have been brought to a darker roast suitable for the espresso cuisine, they usually carry a double-decker name: Dark-Roast Kenya, Colombia Dark Roast, etc. For some advice on choosing among unblended dark-roast coffees see Chapter 6.

Most unblended or single origin coffees also carry a subordinate set of names intended to narrow the growing geography a bit, and spice up the sales pitch on signs and brochures. These names usually represent market names, of which there are thousands in the coffee trade, or grade names, which are only a bit less numerous and confusing than market names, or estate names, which are the names of the farms where the coffees have been grown and processed.

Market names usually refer to the region or district in which the coffee is grown (Mexico Coatepec), the main market town in that region (Guatemala Antigua), the port through which the coffee is shipped (Brazil Santos), or none of the above, which means that the original geographical source of the name has been lost in the mists of time and preserved principally on the burlap of coffee sacks and in the jargon of coffee traders.

Grade names usually refer to the altitude at which the coffee is grown (particularly in central America); to the size of the bean; to numbers of defects (discolored beans, sticks, pebbles, etc.); to the nature of the processing (wet-processing vs. dry-processing); or to cup quality, or how clean and characteristic of the region the coffee tastes.

Altitude is reflected in grading terms like high grown, hard bean (the higher the growing altitude the denser and harder the bean), and altura (Spanish for “height” or “summit”). Grade names keyed to bean size usually are alphabetical (A is the highest grade in India: AA the highest in Kenya, Tanzania, and New Guinea; AAA in Peru). Wet-processed coffees tend to be differentiated from dry-processed coffees by relatively self-evident terms like washed and the Spanish term for washed, lavado. Finally, some grading systems may simply employ a hierarchy of superlatives (in Colombia supremo is the best grade, extra is second-best, and excelso a grade combining beans from both).

To summarize, names may appear like the following: Kenya AA Dark-Roast (a high-grade Kenyan coffee brought to a dark roast suitable for espresso cuisine); French-Roast Oaxaca Pluma (a wet-processed coffee from the Mexican state of Oaxaca brought to an extremely dark roast); Espresso-Roast Sumatra Lintong (a Sumatra coffee that bears the market name Lintong and has been brought to a roast suitable for espresso); and so on.

A brief discussion of single origin coffees and their suitability for espresso brewing appears here. For more detail on single-origin coffees and their cup characteristics see the companion volume to this book, Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing, Enjoying.

Fanciful, Whimsical, or Arbitrarily Romantic Names. These usually describe house blends. In an effort to establish brand loyalty and develop a company mystique most specialty roasters offer house blends, mysteriously named and usually vaguely described (“An exotic blend of robust Indonesian, pungent East African, and brisk Central American growths, carefully proportioned and roasted to bring out the full power and bouquet of these rare and exotic origins. Named after the roastmaster’s favorite niece”). These blends are usually excellent and worth trying. I only wish the copy writers patronized less and communicated more. Many of these proprietary blends are dark-roast and intended for espresso cuisine.

Cocktail or Candy Names. These describe flavored coffees, decent-quality arabica coffees brought to a medium roast, then coated with various flavoring agents. The flavorings are variations of those used in countless other foods. Sometimes nut fragments are added to the flavored beans to dress them up. The names for flavored coffees (Piña Colada, Vanilla Nut. Frangelica Cream) attempt to evoke associations with pleasurable experiences like vacations and dessert, and usually are as carefully contrived as the flavorings themselves. Many specialty roasters refuse to have flavored coffees in their stores; others carry them with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

Since most flavored coffees are brought to a medium roast, they do not figure prominently in espresso cuisine, Some espresso drinkers like to add small quantities of flavored beans to their espresso blends before grinding. See Chapter 9 for a general overview on the use of flavorings in espresso cuisine.

Names for Decaffeination Processes and Social and Environmental Programs. Still another layer of coffee naming has been created by decaffeination processes and organic and other ecologically progressive growing practices.

Decaffeinated or caffeine-free coffees have had the caffeine soaked out of them; they are delivered to the roaster green, like any other coffee. Roasters in most metropolitan centers offer a variety of coffees in decaffeinated form. The origin of the beans and style of roast should still be designated: Decaf French-Roast Colombia, for instance, or Decaffeinated Dark-Roast Special House Blend, etc. See here for details on the various decaffeination processes and their common retail names.

Properly defined, organic coffees are those coffees certified by various international monitoring agencies as having been grown without the use of agricultural chemicals. “Bird Friendly” is a trademark of the Smithsonian Institution that identifies organically grown coffees which also have been grown under mixed-species shade trees. Particularly in Central and South America, these trees provide shelter and forage for migrating songbirds. Shade-grown is a much vaguer term that means that a coffee has been, according to the seller, grown under a canopy of trees—any kind of trees—rather than in full sun. Fair Trade Certified coffees are certified to have been purchased from farmers at prices that, according to a formula prescribed by a consortium of international agencies, give the farmers a reasonable return for their product. Eco-OK coffees are certified by an arm of the Rainforest Alliance to meet an array of balanced environmental and economic criteria intended to assure the well-being of both land and people. An even broader set of criteria is in process of being defined and codified under the general term sustainable, although at this writing that term, like shade-grown, is not limited by any mechanism for definition and certification. In other words, it currently means whatever the user wants it to mean, although that laissez faire situation may change. For more on these issue coffees, see here.

Terms like organic and shade-grown are qualifiers added to all the rest of the adjectives possible to pile onto a specialty coffee name. So, if you’re ready for this, in a specialty store it might be possible to see a coffee named Dark-Roast Swiss Water-Process Decaffeinated Shade-Grown Organic Mexico Chiapas, describing a Mexico coffee from the state of Chiapas that has been grown under mixed shade cover and processed without the use of chemicals, has been treated to remove the caffeine by use of hot water and charcoal filtering, and has been brought to a dark roast suitable for espresso cuisine.

Because specialty coffee roasters justifiably question the viability of their customers’ attention span when confronted with such breathless nomenclature, multiple qualifying terms are usually dispersed in the signage system, relegated to the fine print, or condensed by leaving something out.

Some Other Terms. Here are a last few terms that defy easy categorization: Turkish coffee usually refers to neither coffee from Turkey nor style of roast. The name designates grind of coffee and style of brewing. Turkish is a common name for a medium- to dark-roast coffee, ground to a powder, sweetened, boiled, and served with the sediment still in the cup. As indicated earlier, Viennese usually describes a somewhat darker than normal roast, but it can also describe a blend of roasts (about half dark and half medium), or, in Great Britain, a blend of coffee and roast fig. New Orleans coffee is either a dark-roast coffee mixed with roast chicory root or a dark-roast, usually Brazilian-based, blend without chicory.