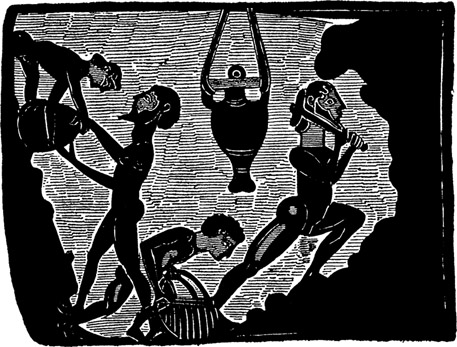

FIG. 13. EMBROIDERY OF A CLOAK, FROM THE FRANCOIS VASE. (Perrot, Vol. X, Fig. 94.)

IF the export of manufactured goods progressed in the archaic period it was not because the manufacturer was urging the ship-owner to find markets for him. For a long time necessaries were supplied by the work of small craftsmen added to that of the family, while luxury was satisfied by beautiful articles from the East. Industry remained thus behind trade until the middle of the VIIIth century. Then, however, the mother cities had to supply their colonies, constantly growing more numerous and wealthier, with arms and utensils, textiles and vases, of every kind. Soon, with the colonies serving as warehouses or manufacturing on their own account, Greece had to supply the increasing demands of the barbarian peoples. It was colonization and trade that set industry in motion.

There was no lack of raw materials. The extension of agriculture had left the poor pastures to sheep-breeding, so wool was found everywhere; it was abundant and excellent in quality on the plateaus of Asia Minor. The purple-shell had been fished from the earliest times in Crete, and the beds of Cythera, once worked by the Phoenicians, were at the disposal of the Peloponnesian dye works. Greece proper was losing its timber, but Asia Minor had the woods of Ida, the peoples of the Ionian Sea provisioned themselves from the thickets of Zacynthos and Italy, and the forests of Thrace were inexhaustible. Potter’s clay appeared on the surface in many valleys. The marble quarries in Paros, Naxos, Attica, and Bœotia were worked more and more. Whereas the Greeks of the epics were ignorant of mining, their descendants extracted copper in Eubœa, where Chalcis the city of bronze became great, and obtained iron in the same island and in Laconia, Bœotia, and the Cyclades.

To take advantage of these resources the Greek craftsmen needed a very thorough training. The civilization of Mycenaean times had not perished utterly. Crete had preserved the secret of the purple and had not forgotten metal-working, the potteries of Melos had not closed, and the immigrants had brought to Asia Minor ideas of craftsmanship which could bear fruit. Even Bceotia had kept something of the education received long ago. But the skilful hand and the inventive mind were lacking. It was then that the Phoenicians brought to the islands the embroidered stuffs of Sidon and the shields of Tyre or Cyprus. It was then that Lydia made known its skill in founding copper, tempering iron, casting and beating gold and electron into jewels or coins, and dyeing wool to weave into carpets or gaily patterned fabrics; Lydia brought into fashion in the rich cities of Ionia long purple garments, elegant footgear, jewels, and perfumes. Cretans and Ionians imitated the foreign products. When they were able to manufacture similar articles they became the suppliers of the other Greeks, who, in their turn, copied their models. The ancients remembered that Cretan artists had worked for Tegea and for Delphi, and that others had left their island for Argos. To confirm this, archaeology follows a certain type of sculpture from Crete to Tegea and Delphi, and even finds it in Ionia and in Attica. The island which had received from outside the pictured shields of Idaean Zeus soon made plating and armour; it sent some to the mainland and thus helped to make good workmen in the forges of the Peloponnese. In the meantime metallurgy was progressing in Miletos, Ephesos, Samos, Chalcis, and Boeotia. These currents, uniting, reached Corinth and Sicyon, iEgina and Athens. From the mother cities the movement spread to the colonies, and from the colonies to the barbarian lands. The bronze-workers of Cumae were the pupils of those of Chalcis and the teachers of those of Capua and the Etruscan cities. The goldsmiths of Miletos taught those of Olbia, who created a Graeco-Scythian art.

Technical education was assisted by the fact that experience was handed down within the family. The son helped his father and succeeded him. Theodoros the bronze-worker of Samos made a statue with his father Telecles. In Chios the sculptor Micciades signed one of his works with his son Archermos, and the tradition was carried on by the two sons of Archermos, Bupalos and Athenis. In Athens the painter Eumares lived on in the sculptor Antenor, Ergotimos bequeathed his pottery works to his son Eucheiros, Nearchos did likewise to his two sons Ergoteles and Theson, and the potter Amasis I was the father of the vase-painter Amasis II. Thus schools of art and workshops were founded in which progress once achieved was permanent.

Industry, thus organized, might have degenerated through routine, but it only inspired initiative and invention. In Corinth the potters thought of mixing an iron oxyde into their clay so as to obtain the fine colour which made their goods so popular. In the same city the naval architects established the plan of the trireme. The Samians, after having a squadron of triremes built by a Corinthian, made a further advance and launched the biggest vessel which had ever been seen. Towards the end of the VIIth century metallurgy was revolutionized by iron-welding and hollow casting. The discovery of a process made the fortune of an individual and contributed to the power of a city.

The progress of technical methods brought into industry a specialization which grew stricter as time went on. The number of trades increased. At the beginning of the Vlth century Athens was not yet a big town, yet a list of trades drawn up by Solon shows the ground covered since the time of the Odyssey. Agriculture, which was once the occupation of all, had become a profession, and the growing of trees, that is of the vine and the olive, is mentioned separately. Sea trade had its recognized place. The arts of Athene were no longer reserved to the family; the textile industry was a separate trade. If the division of labour had gone so far in a medium-sized city it must have been much further advanced in the great urban centres. Many buildings of the period show, for example, how many trades combined in the building industry.

Nevertheless we see from the artistic industries how difficult it still was for the higher occupations to form themselves into specialized professions. The quarry man who extracted the marble was also a stone-mason, who retailed it, and even a sculptor’s assistant, who rough-hewed it on the spot. Even if it was not the same man who did all the work, he worked or made others work in the cuttings themselves, whether he was a statuary assisted by a quarryman or a quarryman employing a statuary. We still find, lying in the quarries of Naxos, Paros, and Pentelicon, kouroi badly roughed in, unfinished gods, and sometimes, beside them, a model. The greatest artists did not yet confine themselves to a narrow speciality. Consider the bronze-workers of Samos: Theodoros, the author of several statues, chased mixing-bowls of gold and silver, a golden vine with jewels for grapes, and the famous ring of Polycrates, which consisted of an emerald set in gold; Rhoecos, who also cast statues, is none the less described as an “architect,” as a ship-builder. In general, sculpture and painting were not distinguished; this was true in the Yth century of Pythagoras of Rhegion and Micon, of Pheidias and Polycleitos, and before them the painter Eumares was the teacher of his son, who is known as a sculptor. One industry, however, seems to have been ahead of the others. In the manufacture of pottery, a very active artistic industry, each kind of work was sufficiently perfected to require a special apprenticeship. From the VIth century onwards the potter made the vase, the painter decorated it, and both added their signature.

The increasing importance of industry can be seen in the position assumed by the workshop. In the Homeric period the Demiurges had gone from one town to another. Even now poets and lyre-players, sculptors, painters, and architects responded to the summons of private individuals, tyrants, or cities. But in industry a considerable change had taken place. To make a shield for Ajax the leather-worker Tychios went from Boeotia to Locris; to-day the famous Boeotian shields were sent out by the manufacturer. This practice was general. Swords came from Chalcis, woollens from Miletos, terra-cottas from Cyprus, vases from one or other of the Ionian towns, from Corinth, or from Athens. The international demand was met by an international division of labour. The craftsman did not leave his residence; he needed apparatus concentrated in the workshop or studio and it was the finished article which travelled.

There were, however, exceptions, which show exactly how far industry developed. At the beginning of the archaic period the small crafts could still carry on with a travelling work-bench. In the Altis at Olympia there have been found, among the bronze statuettes offered ex voto, unsuccessful and unfinished pieces; these were left by the itinerant bronze-casters who came and worked at the temple doors during the festivals. The oldest of the “Cyrenaic” vases were perhaps made by the same hands in different places, for it has been maintained with some probability that the potters went from Sparta to Cyrene with a light apparatus, like the Siphnian potters who in our own time do the round of the islands. In most industries, it is true, the amount of production soon required a permanent plant in fairly large premises. But even then Polycrates summoned to Samos the Corinthian Ameinocles, to build him a flotilla of triremes. Ship-building,

FIG. 13. EMBROIDERY OF A CLOAK, FROM THE FRANCOIS VASE. (Perrot, Vol. X, Fig. 94.)

which could not have become organized and modernized without huge yards, numerous employees, an elaborate plant, a large stock of raw materials, and, in short, a considerable initial outlay, remained faithful to the system of executing contracts at the place of the customer. Medium industry worked actively for export; big industry was not yet born. There were plenty of studios and workshops, but no factories on a big scale.

Among the most remarkable conquests of the new economic system was the textile industry. But, while breaking away from the domestic occupations, it allowed them to continue. It produced hardly anything but luxury goods as yet, and did not yet show any intensity of industrial work. No doubt the long full garments demanded by the Ionian fashion required much material, and the colonies constituted a clientèle which was always ready to give good prices for beautiful work, but, since common stuffs were still woven in the house, the workshops, even those of Miletos, did not aim at quantity. They supplied the aristocracy with fine tissues, artistically decorated, and with many-coloured embroideries which had formerly been imported from Sidon and Lydia. The importance attached to the beauty of the material made dyeing an essential industry. When, later, Sybaris wished to manufacture its own textiles, it began by exempting the fishers and importers of purple from taxation. Fulling was a prosperous trade, practised even in the smallest towns.

The marble industry, which included extraction, cutting, and even sculpture, developed suddenly. It supplied great quantities of blocks, columns, flags, and tiles for building, and basins, steles, statues, and pedestals. While the quarries of Pentelicon and Boeotia hardly sufficed yet except for local needs, the manufacturers and artists of Naxos and Paros supplied the other islands and the great sanctuaries. From the end of the VIIth century the statuary made a point of the difference between himself and the stone-mason, and the oldest signature of an artist which is known to us is that of the Naxian sculptor Euthyeartides.

It is very difficult to judge of Greek metal-working in the archaic period. Rust has corroded the iron. Of the bronze, chiefly works of art have survived. But those old metal-workers of Crete, Ionia, Boeotia, and Chalcis give a high impression of their craft. For a long time they knew only the processes of Homeric times, hammering the sheet of metal over wooden forms and incising details with a point, or else casting the metal solid in hollow moulds. In this way only small pieces could be produced; to compose a large object these had to be put together with clamps and rivets. At the end of the VIIth century Glaucos of Chios invented or imported iron-welding. Shortly afterwards the Samians Rhoecos and Theodoros employed a process, used since the XVIth century in Assyria, which one of them may have learned in Egypt—hollow casting. The bronze-workers of Samos, iEgina, and Corinth were henceforward in a position to execute big pieces in thin metal and, in consequence, to produce pieces of finer workmanship more cheaply. Long before this the Ionian forges had turned out all kinds of objects decorated in the Oriental manner, fittings for furniture and chariots, basins and tripods for which Greeks and barbarians contended from Armenia to the banks of the Saône. The most prized articles of armament were the Boeotian shield, the Chalcidian sword, and Cretan specialities, the mitra and the belly-plate, until Corinth applied quite scientific anatomy to the manu-

FIG. 14.

WARRIOR WEARING THE CORINTHIAN HELMET. BRONZE FROM DODONE. (D.A., Fig. 3452.)

facture of defensive armour, cuirasses, greaves, and helmets fitting all round the head. The metal-workers of Corinth also made beds, and probably, too, a great part of the mirrors which were sold in the west. It is in these industrial surroundings that we must place the work of the great artists in bronze, the bas-reliefs of the Spartan Gitiadas, the marvellous mixing-bowl which Colæos dedicated at Samos, the offerings enumerated in the Lindian Chronicle, and the statues ordered for Olympia from the Æginetan artists Glaucias and Onatas.

But the industry on which we must lay most stress is pottery. It had to meet an extremely large demand. The great mass of it consisted of household ware and receptacles for wine, oil, and ointment. Moreover, the temples required a stock, the size of which can be gauged from the deposits of broken objects. Rich families wanted valuable vases to display at feasts and symposia. Huge pithoi were set on the tombs, or else a supply of clay articles—often very large— was placed inside. In the island of Rhodes one single dead man had by him seventy-nine Corinthian aryballoi, apart from other things. So the pottery trade had to provide for an enormous output. How was this work distributed?

Common crockery was made nearly everywhere, sometimes being merely baked in the sun. But certain centres were engaged in supplying what others lacked. AEgina, for example, was called the “pot-seller.”

Even the manufacture of fine pottery was for a long time scattered over various places. In the days when clumsy, inexpert hands decorated vases with geometrical lines intercourse was rare, and every district had its potters. A few Attic Demiurges made and painted the Dipylon vases for the Eupatrids, while the potters of Laconia and Argolis, Thessaly, Phocis, and Boeotia had a limited clientèle. Other little workshops carried on in the islands, Euboea, Delos, Myconos, Thera, Melos, Crete, Rhodes, Cyprus. There were some, too, in Asia Minor, at Stratoniceia, Miletos, Ephesos, Larissa in Æolis. In those days but few cities sent their goods over the sea, as Miletos did to its colonies on the Euxine.

Everything changed when a healthful wind came out of the East. In the course of the VIIIth century the Greek potters set themselves to imitate the patterns traced on carpets, hangings, bronzes, and jewels from abroad. The Geometric style was succeeded by the Oriental style. Buyers of vases would now have nothing but friezes of animals, and then epic or legendary scenes with human figures. This revolution chiefly benefited the cities from which it had started; types grew diverse and production was concentrated. Miletos was no doubt the source of the ware of reddish clay with a light yellow coating which was so much sold from the Euxine to Italy. Samos, excluded from the Milesian markets, disposed of its alabastra, shaped like female statuettes, everywhere else. Clazomenae found outlets for its grey pottery, and the black ware, the bucchero nero of Lesbos, went to supply models to the Etruscans. At Naucratis the Ionian manufacturers added Egyptian motives to the usual ornamentation, and sent their vases of clay or faience and their ointment pots of opaque or translucent glass into every country visited by the Greeks. Finally, the artistic phials, which have been given the name “Proto-Corinthian” but indicate an Eastern origin by their pretty shapes and the sure tastefulness of their ornament, conquered a wider market than any other pottery of the time. While Asia thus increased its production, the

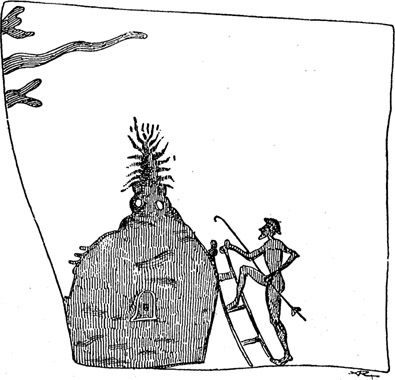

FIG. 15.

EXTRACTION OF CLAY. CORINTHIAN PLAQUE OF TERRA-COTTA. (Perrot, Vol. IX, Fig. 280.)

island workshops closed down, except those of Melos, which saved themselves by the perfection of their workmanship and kept the custom of the Cyclades. In European Greece manufacture was no longer as dispersed as it had been; but the decrease in competition at home did less good to the potters of Boeotia and Euboea, and even to those of Corinth and Athens, than to their Ionian rivals, and the beautiful Laconian ware with a white ground had to be imitated at Cyrene before it spread on the market.

Not until the middle of the VIIth century did the pottery of Corinth make its way to the front rank. There is every sign of a highly organized industry at that time. Between the clay-pit and the workshop, pottery provided a great part of the city with a living. The quarry man attacking a side with his pick while his assistant gathers up the lumps in a basket, or the potter turning the wheel with his foot as he shapes the clay with the paring-chisel, poking the fire with the

FIG. 16.

POTTER AT THE KILN. CORINTHIAN PLAQUE OF TERRA-COTTA. (Perrot, Vol. IX, Fig. 283.)

firing-iron, climbing up a ladder with a hook to break up a flaming kiln, or looking at the batch of pots as it cools—all these scenes were popular, and the men of the trade loved to depict them on the plaques which they hung in the chapels of their quarter. The general public, including the poets, knew the demons which the corporation feared—Syntrips the

FIG. 17.

POTTER AT THE KILN. CORINTHIAN PLAQUE OF TERRA-COTTA. (Perrot, Vol. IX, Fig. 281.)

Smasher, Smaragos the Cracker, Asbetos the Sooty One. To achieve this development the manufacturers of Corinth had been obliged to specialize. In the earliest times they used the common yellow clay provided by nature, and made vases of every shape. When they learned to redden the clay by an admixture of oxydized substances and to depict scenes with many figures, they preferred the big-bellied forms, especially the crater. But they did not trouble about providing delicate

FIG. 18.

DEMOLITION OF A KILN. CORINTHIAN PLAQUE OF TERRA-COTTA. (Perrot, Vol. IX, Fig. 282.)

satisfactions for the sense of beauty. Fine execution and careful detail are not in their line; they produce by the dozen for customers who are easily pleased. The drawing may be

FIG. 19.

KILN FULL OF POTTERY. CORINTHIAN PLAQUE OF TERRA-COTTA. (D.A. Fig. 3038.)

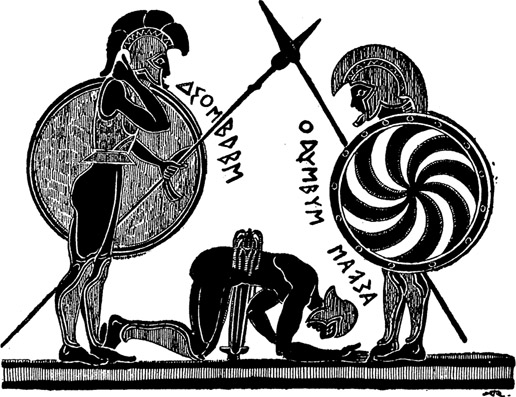

slovenly and the lines may be incised—it’s so easy! If the colours run and lose their brilliance, it can’t be helped! All that is wanted is that they should be varied and showy. To explain the subject to the ignorant buyer a few words of legend are scribbled alongside. If the potters of Corinth were the first to sign their work, it was for business motives rather than from the pride of artists. They must keep on opening up new markets to the boats which sailed packed with vases from deck to hull. The result was magnificent. No Hellenic product was ever so popular or found so many markets as the pottery of Corinth. From 650 to 550 it was exported in quantities to all parts of European Greece, to the islands, to the cities of Asia Minor except Miletos, all along the Euxine, to Syria, to Cyrene, to Carthage, and above all to the western

FIG. 20.

THE SUICIDE OF AJAX, ON A CORINTHIAN CRATER, IN THE LOUVRE. (Perrot, Vol. IX, Fig. 835.)

colonies, to the Etruscans, unequalled customers, and even to the barbarian countries north and west of the Alps.

Spoiled by success, Corinthian pottery made no effort to improve its style. After enjoying for a century the supremacy which it had captured from Ionia, it had to surrender the market to a rival which had been working for this victory for more than two hundred years. Attica contained excellent clays, which took minium well. The craftsmen of the Cerameicos who had made the pithoi destined for the neighbouring cemetery had already proved their technical skill and their spirit of invention by the huge dimensions and varied decoration of these vases. When their successors, by imitating the Oriental type of fauna and flora, had acquired absolute sureness of hand, they made admirable use of the fine glaze which they possessed, contrasting it with the colour of the fired clay. They created the red vase with black figures and, later, the black vase with red figures. With their conscientiousness, their lightness of hand, and their gift of observation they re-instated art in industry, and in the representation of mythical or popular scenes they displayed an originality which was full of power. It was a revelation. Wherevér

FIG. 21.

THE FRANCOIS VASE. BLACK-FIGURE CRATER, SIGNED ERGOTIMOS AND CLEITIAS. (Perrot, Vol. X, Fig. 128.)

taste had become refined these vases were wanted, and no other. Attic pottery perhaps did not spread so widely as Corinthian, especially since it was more expensive; but the total demand was not less, nor, above all, were the profits. The oldest of these vases were still exported by Æginetan and Ionian middlemen. But from 560 or 550 the Athenians took it upon themselves to place wares signed by Ergotimos and Cleitias, Nicosthenes, Execias, Andocides, and many others. They captured the whole market of the Euxine, Cyprus, Egypt, Etruria, Liguria, and the Iberian country. The workshops of Ionia and the islands disappear; the painters of Corinth can get no more work. All the men of the craft who in other times would have founded a firm in their own country, Amasis, Phintias, Cachrylion, and the like, settled in Athens as Metics and contributed to a prosperity based on the complete monopoly of the trade.

It is Attic pottery, then, which gives us the best example of a strong industry before the Persian Wars. The Cerameicos, the quarter which Athene reserved for the fire god Hephsestos, continually spread out into the country. There, in the fire of the kilns, a whole population of workers was busily employed. As a rule they were men of low birth, even the most renowned; their spelling is deplorable and they often bear the names of slaves or freedmen. The increase in number

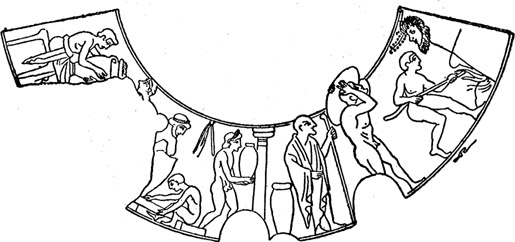

FIG. 22.

POTTER’S WORKSHOP. BLACK-FIGURE HYDRIA, IN THE MUNICH MUSEUM. (D.A., Fig. 3034.)

of slave workers is a certain sign; the master potters needed a fairly large staff. They must have labourers to mix the clay, specialists to shape the bodies and handles (two men to a wheel for the big vases), assistants at the side of the painter to prepare the colours and varnishes, to spread the black lustrous paint, and to finish off the work with a glaze all over, and strong and conscientious workmen for the double firing. Nevertheless a dozen men, or fifteen at the most, were enough to do all this work. A hydria (Fig. 22) represents a workshop opening on a yard. The master or foreman, leaning on a staff, supervises seven or eight workmen; the painter and his assistants are absent, probably because they stay in a closed room away from the noise, dust, and soot. So there is nothing to show that the work which the whole world demanded of the Cerameicos was concentrated in big factories; on the contrary, everything suggests that it was distributed among a multitude of small or medium craftsmen.

Although the signed vases are in a minority, we know about a hundred different makes, covering a hundred years, several dozens being contemporary. The most ancient potters, such as Execias and Amasis, did both the making and the decoration; they had no painter in their employment. No doubt there was not enough work for two masters in the pottery of Nearchos, for his sons, instead of forming a partnership, had each a firm under his own name. In the latter part of the VIth century the most important firms, those of Nicos-

FIG. 23.

AMPHORA OF NICOSTHENES. (D.A., Fig. 7296.)

thenes and of Pamphseos, had quite an industrial character. One reproduced the same type of amphora incessantly, and the other supplied all shapes at all prices, while both followed the changes in public taste and abandoned black-figure for red. Nevertheless, Nicosthenes was able, with his own paint-brush, to decorate almost all his output, and Pamphaeos did his own ornament when he had time. Sometimes several painters worked for the same firm, but they were not attached to it. The vase-manufacturer Hischylos published the work of three painters, but with at least two of them his connexion was only occasional. Siconides decorated black-figure vases for him, as he did for Tleupolemos, and Epictetos, the painter of red-figure vases, went and worked for him as he did for Pamphæos, Nicosthenes, Python, and Pistoxenos. The celebrated Euphronios, after decorating cups for Cachrylion, established himself on his own account and did the whole work in person; only at the end of his career, in the middle of the Vth century, did he take the painter Onesimos into partnership. The intensity of ceramic production in Athens was, in short, an extension in place. This industry was just like the others; the head of an undertaking did not need to collect as much capital and labour as possible, because he was not driven by the necessity of getting the biggest possible return out of expensive machines, in order to diminish his general costs and to obtain a progressive increase in profits.

However it was organized, industry, supported by active trade, seems to have brought in great profits. The craftsmen dedicated rich offerings to the gods. These expressions of pious liberality were subject to a tariff laid down by tradition; the tithe was given. Just as Rhodopis the courtesan sent a tithe of her fortune to Delphi, so the Telchines of Rhodes dedicated to Athene Polias and Zeus Polieus a caldron as “a tithe of their works,” and the potters of Corinth or Athens were no less generous. To pay such dividends to the gods, they must have done splendid business. And we are not much surprised to see a vase-painter representing himself as taking part in an orgy in a sumptuous apartment among gay companions.

In these flourishing industries competition is already keen and bitter. The sculptor proudly puts his name on his work; as he becomes conscious of his talent he desires to distinguish himself from his rivals. The potter and the vase-painter do the same, for the signature is a certificate of origin which will carry the make far. At first the manufacturer signs alone, for customers are only interested in the name of the firm; then he adds to his name that of the painter, which receives increasing consideration; in the end it is generally the artist alone who recommends himself to the public. Personal pride and advertisement. To capture the fashion, an illustrious person is asked for his patronage, and a choice vase is dedicated to him, with a salutation inscribed on it. Sympathies and interests combine; Phintias on a hydria pays a compliment to two confrères. But fighting is not always quite fair; Pamphæos copies the style of Hischylos or Nicosthenes without scruple. A little trumpet-blowing comes in useful, and all the better if you can discredit the shop opposite. On a second-rate amphora Euthymides writes beside his signature “Euphranios will never do as well.”

From individuals, competition extends to cities. It becomes international, keeping pace with the division of labour. The reputation won by the products of a city benefits all who make them. When a modeller of figurines signs himself “Sicon of Cyprus,” or obscure potters add “Athenian” to their name, they give their address and recommend their goods. So keen rivalry sets all the ports capable of contesting the universal market flying at each other’s throats. As long as the Milesians are masters they prohibit access to Asia Minor to Samian pottery, and only allow a few such cargoes into the Euxine, they keep out Corinthian ware so effectively that not the smallest potsherd of it has been found in the ruins of their city, and they manage for a long time to exclude it from Naucratis. When Corinth triumphs, the rivals whom she has ousted vainly copy her shapes and industrialize their methods after her example; she maintains her superiority, and in certain regions, for example at Delphi, she hardly tolerates any goods but her own. By this time the economic struggle is so fierce that it leads to acts of violence and bloody strife. When the Spartans, to show Croesus what their bronze-workers can do, send him a valuable vase, the Samians, out of jealousy, capture the ship which carries it. An insignificant conflict between Eretria and Chalcis is enough to kindle in every part of Greece, one after another, a war without end: Samos declares war on Eretria, Miletos on Samos, Corinth on Miletos, ¿Egina and Megara on Corinth; soon, on the Propontis, the Megarian and Milesian colonies are colliding with the Samian colonies, while in Italy Croton, supported by the Samians, commences an inexpiable war against Sybaris, the ally of Miletos. All this time Athens, which cannot favour either Corinth or AEgina, works and prospers. By their honest, artistic design her vases make Corinthian pottery look cheap and nasty. In vain the threatened manufacturers try to hold their own, in vain Argos and iEgina defend their market by measures of prohibition sanctioned by religious law. Athens is ready, from the middle of the VIth century, to take possession of an industrial and commercial monopoly.