1. The Situation of Industry

IN the Vth and IVth centuries industry in Greece assumed an economic and social importance which did not escape attention. When Socrates would indicate the composition of the Athenian Assembly, before mentioning the husbandmen and the small tradesmen he enumerates the fullers, the shoemakers, the masons, and the metal-workers. The men of the crafts can form the majority; their chiefs become the masters of the commonwealth. Demos gives himself into the hands of lamp-merchants, turners, leather-dressers, and cobblers, and Aristophanes puts this statement into the mouth of a sausage-seller. Moreover, the citizens abandon the lower kinds of work, and in the accounts of public works they appear as an aristocracy of labour, lost in the multitude of Metics and slaves. Nor was Athens an exception. The little towns of the Peloponnese swarmed with craftsmen; their military contingents were almost entirely formed of men with professions. The industrial callings even attracted women. Many freedwomen and daughters of citizens reduced to need devoted themselves to the works of Athene Ergane. They wove for custom, they sold yarn, ribbons, clothes, and bonnets of their own making, or they plaited wreaths.

But, if a great part of the population lived by industry, it does not follow that it was industry on a large scale. First, we must not be misled by the concentration of many workshops in the same city or in the same quarter. We involuntarily think of the great manufacturing towns of modern times when we see the Cerameicos in Athens entirely occupied by the potters, the tanneries collected outside the city, the Peirseeus filled with workshops which manufacture imported raw materials and work for export, and Laureion inhabited by a whole people of miners and metal-workers. In order not to misinterpret this concentration, it is sufficient to recall analogous facts. There are also in Athens a Street of the Box-Merchants and a Street of the Herm-Sellers, and the craftsmen teem round the Agora. The workshops are innumerable. Some are big enough to be called factories, but none is a huge concern of the modern kind. Rival manufacturers live next door to each other; they are jealous of each other, but the struggle is not bitter, for there is work for all and the weak are not crushed by the strong. Small

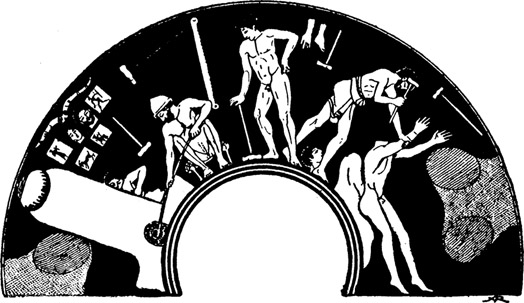

FIG. 38. SPINNING-WOMAN DRAWING OUT HER YARN. CUP FROM ORVIETO. (D.A., Fig. 3382.)

industry predominates; medium-sized industry plays a certain part; large industry barely makes a vague appearance.

The first cause which prevented one whole class of industries from developing indefinitely was the persistence of work in the home. At the time when the miller Nausicydes and the baker Cyrebos were each amassing a great fortune, housewives were still employed, like their grandmothers, in pounding the corn and kneading the dough. They kept the manufacture of clothing in their hands from the moment when the fleece was brought to them to the moment when they gave their menfolk the finished chiton. The greatest ladies of Greece taught their daughters everything connected with the making of clothes. Like the wise Arete, Queen of the Phseacians, the mother of the tyrant Jason span and wove in her palace. Everywhere the mistress of the gynaeceum

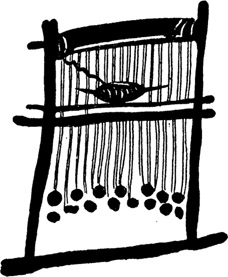

FIG. 39. THE WEAVING-LOOM. BOEOTIAN VASE OF THE VTH CENTURY. (D.A., Fig. 6845.)

held, in Plato’s words, “the government of shuttles and distaffs.” Indeed it was in these home work-rooms that an industry which worked for the public was born. For that

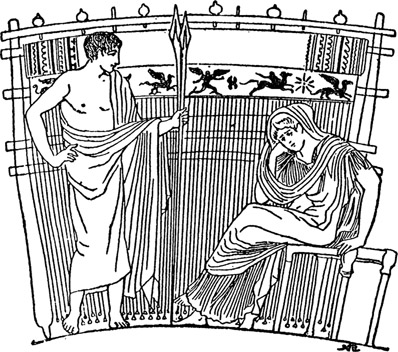

FIG. 40. THE WEB OF PENELOPE. VASE FROM CHIUSI. (D.A., Fig. 6844).

it was sufficient that the output should exceed the requirements of the house and that the surplus should be sold. This might happen without fixed intention, but it was also done with the deliberate purpose of practising a profession. In this way Athens manufactured men’s clothing; Megara specialized in the worker’s exomis; Corinth put on the markets its blankets, its kalasireis of fine wool, and its linen cloth; Pellene made cloaks which were in great demand; Patrse was filled with women, thanks to its byssos weaving-works; Cos had a name for its bombyx silk goods; Chios, Miletos, and Cyprus sent their hangings, their embroidered garments, and their carpets far and wide; Taras grew rich on its linen stuffs; and Syracuse transformed the wool of Sicily into textiles of many colours. But the textile industry, even when it had become a special profession, produced in small quantities. For common materials, the families only turned to it for a supplement to their own output, and preferred to call in women by the day. For the finer qualities manufacture was scattered and the demand limited.

Even those industries which were entirely in the service of the public kept some traces of the family system. The son fairly often succeeded his father. In the liberal careers the case was very frequent; the schools of medicine and music were family groups, the history of sculpture and painting is that of a few houses, and the architects of Delphi were, in succession, two Agathons, then Agasicrates, the son of the second, and lastly Agathocles, the son or brother of Agasicrates. In the same way the industrial art of the potters was handed down in the family. “How long,” says Plato, “the potter’s son helps his father and watches him at work before he touches the wheel himself!” In the other industries we find similar examples, but they are far fewer. Cleon inherited a tannery from his father, Anytos left one to his son, Lysias and his brother Polemarchos began by manufacturing shields like their father Cephalos, Athenogenes made perfumes like his father and grandfather before him, and among the contractors at Eleusis we see Antimachos son of Neocleides succeeded by Neocleides son of Antimachos. But each chose his own profession freely, and we see manufacturers’ sons eager to escape from the paternal mill and to plunge into politics. The exodus of men from the country contributed to the recruiting of the industrial class, while the sons of craftsmen became artists, doctors, and orators. Individuals went from one profession to another with extreme mobility. Hereditary professions were not the rule.

In any case there was nothing like the great factory with countless hands. The largest establishment of which we know in Attica was the shield factory which the Syracusan Cephalos founded in the Peiraeeus in 435 and handed down to his sons. In 404 it contained 120 slaves. After that come the two houses managed by the father of Demosthenes. For the people of the time these “were neither of them small industries.” Now the arms factory had 32 or 33 slaves, the bed factory 20. A shield factory bequeathed to Apollodoros did, it is true, produce twice the output of the armoury bequeathed to Demosthenes, and therefore may have contained twice the personnel. Even then we have only one industry which employed more than a hundred workers, and those which employed more than twenty were considered very large. The celebrated potter Duris probably had not more than a dozen men about him. The gang of shoe-makers inherited by Timarchos consisted of nine or ten slaves, and in a mime of Herondas the fashionable shoe-maker has thirteen. The mines, it is true, present a very different aspect; there slaves were hired by the hundred. But when a man needed a big staff of working miners it was because he had obtained by auction a large number of small concessions. The State only gave out small lots. The typical mine employed about thirty men underground, about the same in the washing-room, and far less in the foundry. We know of one concessionnaire who put his hand to the pick and had for total capital a sum of 4,500 drachmas; with such initial assets he cannot have had more than fifteen or twenty workers under him.

Athenian industry, then, never involved a great agglomeration of workers in one undertaking. What is typical of this industry is not the factory in which Cephalos collected over a hundred hands, but rather the hovel in which the Micylos of the poet Crates cards wool with his wife “to escape starvation,” or the workshop in which, according to an inscription, the helmet-maker Dionysios worked together with his wife, the gilder Atremis. And these are not accidental, isolated cases. The Athenian craftsman had no interest in increasing the number of his workers, Xenophon says. He was in the same position as the farmer, who knew exactly how many day-workers he needed, and that one man above this number was a sheer loss.

Whether they were conducted by the family or by a single owner, these workshops with their small personnel did not require much capital. As a rule, big fortunes, even in a city like Athens, were rare, and, being exposed to the risks inseparable from investments at high rates of interest, they were ephemeral. But industry did not attract them especially, and it did without them. A small foundry was worth 1,700 drachmas, including slaves. Even the mines could keep going without a great concentration of capital; one concession of the normal type with thirty slaves served as security for a loan of 10,500 drachmas, and another for a mortgage of one talent; and a man with 4,500 drachmas bid at the auction. It might be supposed that ship-building at least would have required huge yards and the formation of big companies. It had to supply a merchant fleet which covered the whole Mediterranean and a war navy which had 300 vessels in the Vth century and over 400 in the IVth. But what do we see in reality? One hundred and eighty-three ships, the builders of which are known to us, were launched in fifty-two years from fifty-nine different yards. It was the same with the public works contractor. With the system of giving orders in small lots and paying by instalments in advance, he did not need to have much money. When craftsmen united for big jobs it was the labour of their little firms that they were combining. Even those factories which prospered do not seem to have been capable of enlargement by the increase of capital. The banker Pasion would have had no difficulty from the financial point of view in extending the factory which was already bringing him a talent a year; yet he did nothing of the kind. Demosthenes’ father obtained an income of only 30 minas from his armoury; in his bed factory he sank only a capital of 40 minas and a floating capital of 150 minas; apparently he did not see his way to developing these two concerns, since they did not prevent him from buying a house for 30 minas and drawing 177 minas interest a year on loans and deposits. Timarchos did not increase his staff of nine or ten shoemakers; he preferred to acquire a weaving-woman and an embroiderer, and invested in land. Conon had a bonnet-weaving establishment and a drug business, without either workshop suffering from the existence of the other. In the Peiræeus we find a workshop with dwelling-quarters rented for 54 drachmas; nowhere do we find a great factory representing a fortune.

For the soul of the great factory is the machine; and without machinery the great manufacturer does not supersede the craftsman. The slaves were quite enough for the output; there was no need to rack one’s brains to cope with shortage or dearness of labour. The Greek engineers distinguished between simple machines and composite machines. The former were five in number, the lever, the wedge, the

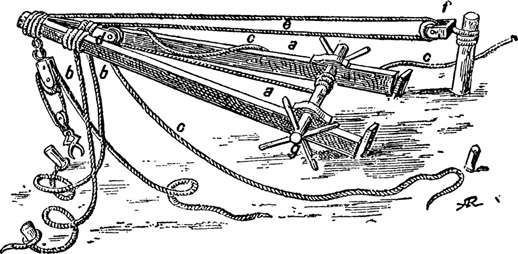

FIG. 41.

HOIST, BEFORE SETTING UP. (D.A., Fig. 4745.)

a, wooden legs; b, fore-stays; c, back-stays; d, upper block; e, gear-rope; f, lower block, fastened to a pile; g, windlass.

screw, the windlass, and the pulley or block. The latter were merely combinations of the former, and the only one known in the Vth century was the crane. Archytas was the first to apply geometry to mechanics; he caused perceptible progress to be made in the theory and practice of the lever, and solved several problems of traction, to the advantage of construction and shipping. But no advance was made beyond the apparatus invented by the architects Chersiphron and Metagenes for the land transport of heavy material. Loads were lifted with the help of two-legged machines or sheers. These were erected in yards and on harbour moles. In the mines the shortness of leases and the cheapness of labour retarded technical progress. Since the only object was the immediate return, and no one troubled about making extraction easier for future concessionaires, the section of the galleries was small, no winding plant was installed at the pit-heads, and mechanical crushing was unknown; all the work was done by strength of arm. The smelting and refining furnaces, though not expensive, were fairly developed, but they did not make it possible to separate gold from silver. The bronze-workers obtained wonderful colour-effects, but this metal polychromy was attained by the simplest methods, incrustation, the juxtaposition of different alloys, gilding, silver-plating, or patient, skilful patination. By Callias’ process certain dye-stuffs were extracted from argentiferous lead, in particular cinnabar or vermilion, but always without any expensive plant. The same is probably true of the process invented by a woman of Cos for winding silk-cocoons. The vase paintings often represent workshops with a few implements hung on the walls. (See Figs. 44-46.) It is Greek industry that we see here, with its apparatus of primitive simplicity and its low output.

It made no great demands in respect of raw material, either. This was often supplied to the craftsman by his customer. The family which could not weave enough cloth for itself gave yarn to a workwoman, who wove it in the house or at her own home. In a play of Aristophanes a goldsmith and a harness-maker go to a house to mend a clasp and a strap. When he wanted some building done, Timotheos procured timber from Macedonia. When the State undertook public works, it divided them up into lots and chose in each case between two systems, either doing the work itself or giving it to a private contractor. The latter method had the advantage of laying all the responsibility on one or more contractors. The former was necessary for difficult work which required artistic perfection or, where the task could not be divided up, a comparatively large quantity of personnel, materials, and capital. For the work which it did itself the State supplied everything. It bought the gold and ivory from which Pheidias was to make the statue of the Goddess. For other statues it procured copper and tin, fuel for the casting, and the beams and planks of the inclined plane and the platform. If column-drums had to be brought to the site, it made a road, built waggons, and only asked the transport agents for beasts at so much a day. It would instal a windlass at its own cost and give the iron-work out on contract; it procured tools for the workmen and had them steeled when they became worn. It was to relieve itself of these cares that the State turned more and more to the contractor. Yet it still supplied him with scaffolding, stone, wood, lead, iron, and bronze. When an administrative body decided to adorn a temple with a monumental entrance, it began by acquiring cedar or cypress, ivory, glue, and pins. If the contractor must himself supply the materials or engines needed, if the mason was to furnish common stone for the foundations, or if the carpenter was to bring his own scaffolding, this condition had to be expressly stipulated. The ordinary rule was that the craftsman sold his labour and nothing else.

All these advantages did not, however, draw a very large number of contractors, especially of such as had considerable means at their disposal. The State tried all manner of devices to divide up the lots and to organize competition; orders were brought within the power of the humblest workers, alone or in partnership; craftsmen were summoned from one town to another, and sometimes from great distances. At Delphi an order for stone which comes to about 1,100 drachmas occupies five quarrymen, one from Argos, two from Boeotia, and two from Corinth; other work is given to contractors as far as Arcadia, and they are allowed their living-expenses so long as the contract is in hand. At Epidauros the lots are less split up than anywhere else; one of them even reaches the figure of 14,000 Attic drachmas. But on this occasion the whole of Greece was making a supreme effort. A painter came from Stymphalos, the cypress-wood was supplied by a Cretan, and the heralds went cadging for tenders from Tegea to Thebes. We even know of two contractors in Argos who bid for orders first at Epidauros and then at Delphi. Argos in her turn, to build her Long Walls, sent to Athens for skilled workmen. Athens herself always gave out small orders which small contractors could undertake. The work on the Erechtheion was the occasion of a vast number of small payments. The largest sum mentioned in the Eleusis accounts of 328, amounting to 7,087 drachmas, was paid for binding the windlass with iron, i.e. for an indivisible operation; then comes an order for quarrying, transporting, and laying stone, which amounts to 2,660 drachmas; after which only one or two items rise above 500 drachmas. And foreigners followed the contract-auctions in Attica as keenly as elsewhere; out of twenty orders put up to auction at Eleusis, thirteen were secured by twelve Metics, as against seven which went to two citizens. For such competition to be allowed, desired, and actually encouraged everywhere, each city in Greece must have felt incapable of accomplishing by her own resources any project of public works which rose above the ordinary.

Puny as industry was, it could not always confine itself to executing orders. Sometimes it produced in advance. The retailers and exporters enabled the craftsmen to work regularly without troubling too much about the demand. The shoe-maker made to measure and sold ready-made. The armourer had to provide for sudden, large demands. When the Thirty confiscated the factory of Lysias and Polemarchos, they found in stock great quantities of gold, silver, and ivory, and seven hundred finished shields. In Thebes a band of insurgents broke into the armourers’ shops and fitted themselves out with lances and swords. But the craftsmen had no advantage in producing without cease and sinking capital in the shape of stock. The demand was too restricted. Even the armourer was afraid of the repercussion of political events. Demosthenes asks his guardian why his armour works have paid nothing during his minority; it is not, he says, for want of work, as is proved by the accounts of the output; then is it because the arms manufactured could not be sold? Here, certainly, we have over-production. And here we have its effects: in Aristophanes the merchants weep over the cuirasses, trumpets, crests, helmets, and javelins for which they cannot find buyers. As a rule the manufacturer made his arrangements so that production should not outstrip orders to a dangerous extent, and hired out the slaves whom he could not employ. In the IVth century he was perpetually concerned with keeping his personnel down to what was absolutely necessary. According to Xenophon, once the blacksmith or bronze-worker neglects to regulate his work by his sales, “down goes the price of his goods, and his business is ruined.” If the industry of Laureion yas the only one which absorbed labour indefinitely, it was because only the silver-market absorbed output indefinitely.

The returns of industry reached a high figure. In comparison with the natural product, the manufactured product was dear. Its price had to be in proportion to the normal interest on money and the remuneration of labour. The sums paid for the hire of slaves give valuable information on this point. Xenophon reckons that if the State buys 1,200 miners, and uses the hire paid for their labour in buying more, it will be able to raise their number to 6,000 in five or six years. If, therefore, the obol paid each day for each miner is capitalized for about five and a half years it will be possible to multiply the number of miners by five; this represents an annual profit of 33% on slaves who cost on an average 180 drachmas. For the skilful worker the hire is greater, but so is the purchasing price. Let us see what Demosthenes’ father gets from his two factories. From 20 cabinet-makers he obtains a yearly profit of 12 minas, i.e. one obol per man per day. But together they are worth at least 40 minas. Thus they bring in at most 30%). His 32 or 33 armourers bring a net yearly profit of 30 minas; according to the orator, whose interest it is to exaggerate, they are worth “up to five and six minas per head, and never less than three,” or an average of three or four minas; so the income is between 23% and 31%. Lastly, as daily hire for his shoe-makers, Timarchos takes 2 obols per man and one obol extra for the foreman; at 4 minas a man and 6 minas for the foreman, we again get 30%. In sum, below 25% the income from industry is on the low side, above 30% it is rather high. When iEschines the philosopher wanted to open a perfumery business he borrowed money from a bank at 36%; it was sheer madness. But to repay this debt he obtained funds at 18%. Then he might have made a success, if he had only had the qualifications of a manufacturer.

At 30% the income from industry was equal to two and a half times the normal interest. But it entailed a fairly big risk, the death of the slaves. A percentage must be deducted as sinking-fund. If the slave in the mine gave in appearance a rather higher return than the slave who made furniture or shoes or metal goods, it was just because his work was more unhealthy and his life more exposed. The difference in return did not therefore depend on the number of persons employed, i.e. the size of the concern. The plant was neither so complicated nor so expensive that concentration in a single concern would diminish the general costs. Small-scale industry was at least as remunerative as large- scale. Fortunes were made in the mines which were enormous for the time. By lucky digging, Callias made the 200 talents which earned him the nickname of Laccoplutos (Grubenbaron, as the Germans say); his son Hipponicos passed for the richest man in all Greece; Nicias owned 100 talents; the firm of Epicrates realized that sum in a year; when Diphilos was condemned to the confiscation of his property for illicit exploitation, 160 talents were found in his coffers. But the Athenian who invested a large capital in mining business had no other advantage over the man who risked only a few thousand drachmas than that he acquired several concessions at once. He increased his profits only in arithmetical proportion. He even added, to the expenses which would fall on several small concessionnaires, the cost of a manager, which was very heavy. This question of the return covers all the rest, in the sense that there is no industry on a large scale where the amalgamation of small concerns does not ipso facto cause a considerable saving.

But we should have a very incomplete notion of Greek industry if we neglected the moral aspect. In a people with a lively imagination and acute wits the crafts readily assumed an aesthetic character. Here there was no machine ruling over the man who minded it, and forcing him to repeat the same motion over and over again, as if he were himself an automatic driving-gear. Tasks were not necessarily monotonous; they might even develop a natural bent. There was no mass production, done in feverish haste, piled up in the darkness by nameless hands. The craftsman did his work in a little workshop under the eyes of the passer-by. He did not drudge at it from morning to night, but took his time to finish everything that passed through his hands. Even for export he was asked to supply articles of value. Eye and hand were exercised at leisure, amour-propre was aroused, and technical progress was achieved in a glad spirit. This joy in work, the collaboration of creative thought and obedient tool, the love of free play ennobling the daily endeavour, all this somehow shed a ray of light on the commonest object and made the workman an artist. Was he a sculptor or a mere decorator, the Thrasymedes of Paros who chiselled the chryselephantine statue of Asclepios at Epidauros, and then executed doors of cypress-wood plated with ivory and a coffered ceiling? What name are we to give to the marble- workers who earned a modest wage cutting fine flutings on the columns of the Erechtheion? When the Cerameicos potter made and decorated humble receptacles for oil and wine, he was a Greek working for Greeks. The air which blew about the working quarters of Athens had passed over

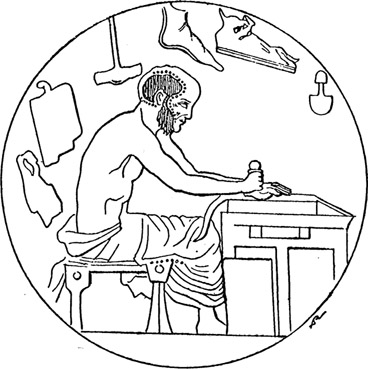

FIG. 42. THE VASE-PAINTER. ATTIC CUP. (D.A., Fig. 7340.)

the Parthenon, and in it the lowest workman breathed a spirit of perfect harmony. By personal endeavour new forms and motives were invented without number; even the busiest workshops did not reproduce their models twice. Plato’s contemporaries could say of industry, as of art, “Everything that we Greeks take, we transform into beauty.”