CHAPTER 6

Something Horrible Happened

I joined the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at the Bank of England in July 2006. I didn’t apply for the job. I read in the Financial Times that the UK government was looking for a replacement for Professor (now Sir) Steve Nickell, whom I had known for years. I eventually got a call from (now) Lord Nick Macpherson, Permanent Secretary of the Treasury, asking if I was interested.1 A couple of weeks later I was on holiday at the Boulders Resort in Arizona and got the call that they wanted to offer me the job. I accepted and served on the MPC from 2006 to 2009. During the second half of that term, from around October 2007 onward, I started to vote for rate cuts, all on my own. Believe me, it was the worst time of my life. Eight people on the MPC had the same opinion and I had a different one, so there were only two opinions. I have to admit that I felt like I had the weight of the British people on my shoulders. I felt totally isolated. As the famous Liverpool FC battle cry from the Kop End, the old Gerry and the Pacemakers song goes, “Walk on with hope in your heart and you’ll never walk alone.” I had no hope and felt like I was walking alone. Some years later Gordon Brown, who was absolutely excellent during the crisis, called me up and apologized for appointing me “to that awful job.” I still believe Gordon Brown and Ben Bernanke saved the world.

I commuted to the UK every three weeks from my home in New Hampshire, and during 2007 and the early part of 2008 I watched as shops started closing in the towns in the Upper Valley—Lebanon, White River Junction, Claremont, and Windsor.2 The housing market started slowing and house prices turned downward. The patterns I saw where I lived suddenly started to appear in the UK. The pandemic had started to spread. Too few people were watching. Nouriel Roubini, otherwise known as Dr. Doom, had also spotted that a downturn was coming. Some years later he and I commiserated on what had happened and that nobody much had listened to our warnings on a beach in Bahrain after we both gave talks there, waiting for our delayed long-haul flights home.

While Rome Burned

Turning points are especially hard for forecasters to spot. When the good times roll they think they will continue forever, and vice versa when the downturn comes they are too optimistic. This is what happened in 2008. Policymakers in government and central banks missed the big one because economists whose job is to warn of impending doom failed to do so. The job of volcanologists is to predict when a volcano will erupt. Weathermen are supposed to be able to predict when hurricanes will hit. Macroeconomists are supposed to spot recessions.

It is instructive to examine the economic projections reported by members of the FOMC during 2008. For simplicity, I report the central tendencies, which exclude the three highest and three lowest projections. In January the projections for GDP growth were, as percentages, as follows:

2008 |

2009 |

|

January 2008 |

1.3 to 2.0 |

2.1 to 2.7 |

April 2008 |

0.3 to 1.2 |

2.0 to 2.8 |

June 2008 |

1.0 to 1.6 |

2.0 to 2.8 |

October 2008 |

0 to 0.3 |

-0.2 to 1.1 |

January 2009 |

-1.3 to -0.5 |

|

April 2009 |

-2.0 to -1.3 |

The actual quarterly GDP outcomes reported in 2018, after a long series of revisions, were as follows:

Q1 2008 |

-0.68 |

Q2 2008 |

0.50 |

Q3 2008 |

-0.48 |

Q4 2008 |

-2.11 |

Q1 2009 |

-1.39 |

Q2 2009 |

-0.14 |

Q3 2009 |

0.33 |

Q4 2009 |

0.97 |

The FOMC missed the big one; the central tendencies had no negatives for 2008, and they were unduly pessimistic for 2009. The transcript of the Fed’s meeting on September 16, 2008, when it kept the federal funds rate at 2 percent, only has a couple of mentions of a recession. The most notable quote is from Chairman Ben Bernanke, which has a hint of something coming: “I think what we saw in the recent labor reports removes any real doubt that we are in a period that will be designated as an official NBER recession. Unemployment rose 1.1 percentage points in four months, which is a relatively rapid rate of increase. The significance of that for our deliberations is, again, that there does seem to be some evidence that, in recession regimes, the dynamics are somewhat more powerful, and we tend to see more negative and correlated innovations in spending equations. So, I think that we are in for a period of quite slow growth.”3

The transcript makes clear at the very outset that there was deep trouble on Wall Street: “The markets are continuing to experience very significant stresses this morning, and there are increasing concerns about the insurance company AIG. That is the reason that Vice Chairman Geithner is not attending.”4 On Saturday, September 13, 2008, Timothy Geithner, then the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, called a meeting on the future of Lehman, which included the possibility of an emergency liquidation of its assets. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy protection on September 15, 2008, the day before the FOMC meeting.

Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren told my Dartmouth class “Financial Crisis of the Noughties” some years later that it would have been possible to rescue Lehman Brothers over the several months after Bear Stearns collapsed in March 2008. By September 15 when Lehman filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy protection it was too late as they were already insolvent. The job of the central bank is to help solvent but illiquid banks, not the insolvent. Clearly opportunities were missed.

I got into big trouble at the start of 2008 when I did an interview with Ashley Seager, at the Guardian, where I said the MPC was “fiddling while Rome burns.”5 In testimony to the Treasury Select Committee in the House of Commons that oversees the MPC, I worried on March 28, 2008, about what might happen: “My concern would be one should make sure one is ahead of the curve so that later one is not in a position where something horrible happens, I do not want that to occur. My risks are to the downside and I have concerns that something horrible might come and I do not want that to happen.”6 Sadly, something horrible did happen.

Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England, made it clear throughout 2007 and 2008 that the United States was irrelevant to the UK. At the Treasury Select Committee MP Andrew Love asked King whether he was concerned that U.S. recession might spread to the UK (Q38, March 26, 2008). “For us, far more important than the United States in terms of the impact on demand in the UK is the impact on the euro area because they have a weight three times larger than the United States in our trade-weighted index, so what happens in the euro area is much more important to us directly than the US economy.” The governor of the Bank of England had no idea what was going on in the British economy in 2008 as the biggest recession in a hundred years hit. The two countries had not decoupled. It turned out that when the United States sneezed, the UK caught pneumonia, from which it still hasn’t fully recovered.

Lord King even said this, sitting two seats from me on March 28, 2008, three days before the Great Recession started, giving testimony to the Treasury Select Committee at the House of Commons: “I do not think we really know what will happen to unemployment. At least, the Almighty has not vouchsafed to me the path of unemployment data over the next year. He may have done to Danny, but he has not done to me.”7

It wasn’t just in the UK that forecasters were hopeless. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, in their October 2008 report, forecast world output to grow in 2009 by 3.9 percent. Country forecasts were: United States, 0.5 percent; Germany, 0 percent; France, 0.2 percent; Italy and Spain, -0.2 percent; Japan, 0.5 percent; UK, -0.1 percent; and Canada, 1.3 percent. It didn’t turn out that way. Moises Schwarz, the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Officer, argued that “the IMF’s pre-crisis surveillance mostly identified the right issues but did not foresee the magnitude of the risks that would later become paramount” (2016, 1).

Larry Kudlow, President Trump’s director of the National Economic Council, called it precisely wrong in December 2007, the month that the United States entered recession.

Yesterday’s tremendous ADP jobs report puts the dagger into the very heart of the recession case. The fact is, America is working. Look at how close the reports parallel one another. So here’s my point: Jobs aren’t folding. Jobs aren’t plummeting. Jobs are strengthening. Now I’m not smart enough to know what the jobs number is going to be tomorrow, but you could easily have a blockbuster 200,000 jobs report. I don’t know, it could be 150K, it could be minus 600K, but I highly doubt that folks. When you see this kind of ADP report, you’ve got a whole new situation…. There ain’t no recession.8

The same day Kudlow’s comments were published the official data release from the BLS showed that the unemployment rate rose from 4.7 percent to 5 percent and the number of unemployed rose by 474,000. Non-farm payrolls were +18,000 while private non-farm payrolls fell 13,000.9

Kudlow was at it again in November 2018, arguing that “the basic economy has reawakened and it’s gonna stay there. I mean, I’m reading some of the weirdest stuff, how a recession is around the corner—nonsense. My personal view, our administration’s view, recession is so far in the distance I can’t see it.”10 Maybe he is right this time, but maybe he isn’t.

The MPC produced a forecast in August 2008 that I have to admit I signed on to—and the main inflation report that accompanied it never made any mention of recession. I am so embarrassed. A couple of weeks earlier the first estimate of quarterly GDP growth was reported by the ONS for 2008 Q2 of +0.2 percent. I had expected the number to be negative and that number threw me for a loop. By that point I had started to doubt that I was right. I went home after the meeting in early August with the intention of resigning as I was clearly so wrong.

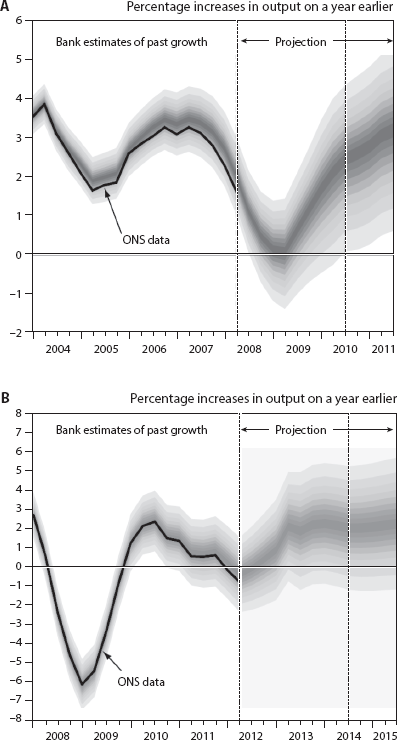

Figure 6.1A is the MPC’s forecast for quarterly GDP growth. The first vertical line in 2008 is where we were at the time of the forecast. The shaded bands depict the probability of various outcomes for GDP growth. To the left of the first vertical dashed line, the distribution reflects the likelihood of revisions to the data over the past; to the right, it reflects uncertainty over the evolution of GDP growth in the future. If economic circumstances identical to those during the time the forecast is made were to prevail on 100 occasions, the MPC’s best collective judgment is that the mature estimate of GDP would lie within the darkest central band on only 10 of those occasions. The chart is constructed so that outturns are also expected to lie within each pair of the lighter areas on 10 occasions. Consequently, GDP growth is expected to lie somewhere within the entire fan on 90 out of 100 occasions.

Figure 6.1. (A) MPC August 2008 GDP projection based on market interest rate expectations. Source: Bank of England. (B) MPC August 2012 GDP projection based on market interest rate expectations. Source: Bank of England.

The fan narrows to the left, as data revisions occur and we become more certain about the actual data. The black line shows the official data. The fact that the majority of the shaded fan in the backcast is above the line means the MPC expects data revisions to pull up the data. The forecast to the right has a trumpet shape as it is harder to forecast further into the future. The forecast horizon is where the MPC is focused on given that it takes about two years for its actions to have an effect. The forecast suggests that the MPC is 90 percent confident that GDP growth on a year earlier will be in the interval from around 0.5 percent to just over 5 percent. The saddest thing is that it predicted that there would be no recession—and no quarters of negative growth.

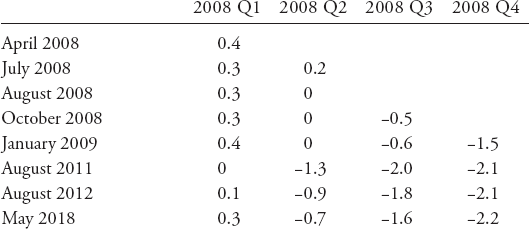

GDP data are subject to revision, especially at turning points. Growth in 2008 Q2 was revised down a lot; as I noted earlier, GDP fell by 6.3 percent, peak to trough. In the table below I report the revisions for four quarters of data in 2008. I present the initial estimate and those prevailing in May 2018, as well as a couple of intermediate dates.

It took until May 2009 for the 2008 Q2 estimate to be revised to a negative number and confirm the start of the recession, given that the third quarter was always negative. By May 2018 the 2008 Q2 figure had been revised from +0.2 to -0.7 percent. The third and fourth quarters had downward revisions also. By May 2018, 2009 Q1 and 2009 Q2 are confirmed as being negative at -1.5 percent and -0.2 percent. It is also difficult to estimate upturns; the initial estimate for 2009 Q3 in October 2009 was -0.4 percent; by May 2018 the number had been revised to +0.2%. At upturns the statistical authorities are more likely to underpredict what is happening.

Figure 6.1B, taken from the August 2012 inflation report, shows what happened. Output collapsed and there were five negative quarters. It is also apparent from this figure that in August 2008 the UK was already in recession. We didn’t know where we were. We didn’t know where we had been, and we didn’t know where we were going. Same as now.

Northern Rock

It is not as if there weren’t adequate warnings. During my time on the MPC I watched as thousands of people lined up outside Northern Rock when its website failed. The world was treated to the scenes of a good old bank run. Depositors waiting in line around the country to withdraw their cash. Shin (2009) has noted that the last time that happened was at Overend, Gurney, a London bank that got in trouble in the railway and docks boom of the 1860s.

Britain’s deposit-insurance scheme guaranteed fully only the first £2,000 of deposits, and then 90 percent of only the next £33,000. It was sensible to run to the bank to get your money. Northern Rock relied on wholesale markets rather than on retail deposits to finance most of its lending.11 In January 2007, it announced record pretax profits of £627 million for 2006, up 27 percent on the previous year. As the MPC was pushing interest rates up, from 4.5 percent in July 2006 to 5.75 percent in August 2007, Northern Rock had agreed to issue a tranche of mortgages at interest rates lower than those it eventually had to pay to finance them. Northern Rock was in trouble.

The Bank of England emphasized the concerns over moral hazard. They wanted to send a message that if bankers took excessive risks they could not look to the central bank to rescue them from the consequences. On September 13, 2007, Alistair Darling, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, had little choice but to agree that the central bank should provide emergency funding to Northern Rock. The run started on the evening of September 13, following the news that a well-known bank had gone to the Bank of England for help.

Northern Rock had seventy-two branches in total, and only four branches in London. Many branches had only a couple of counters because the bank did not normally conduct much of its retail business over the counter. Because of money laundering requirements, large withdrawals could take several minutes to be completed. As the Treasury Select Committee (TSC) noted, these factors together explained why it did not take many customers seeking to withdraw their funds for queues to extend out the front door and into the street—and into the public consciousness.12

Lines started to form outside branches of Northern Rock on Friday, September 14, as the share price fell 31 percent on the day. Lines continued to form the next day, Saturday.13 On Monday, September 17, shares opened 31 percent lower. With lines forming again. Alistair Darling intervened, pledging that the government would guarantee all deposits. Northern Rock was eventually nationalized on February 17, 2008. The run was halted. The man in the street was rightly upset at the failure to stop a bank run. The Bank of England knew well before it failed that Northern Rock was in trouble and did nothing about it.

It was obvious that if Northern Rock, which depended on access to wholesale money markets and had relatively few depositors, was in trouble so would be others that were dependent on that source of funding. At the top of that list were two building societies, Alliance and Leicester (A&L) and Bradford and Bingley (B&B), but nothing was done by the Bank of England. A&L was taken over by Santander in 2008 after its shares fell by more than 80 percent.14 The latter was eventually sold to Abbey National, after running into “difficulties.” Henry Wallop at the Telegraph made clear how bad things were, noting that in 1999 shares in B&B were 247 pence. By mid-September 2008 they “were worth just 20p, as the full scale of the UK housing market crash, and the global financial turmoil, made the headwear of choice for B&B shareholders a tin hat rather than a bowler.”15 DeAnne Julius, a former member of the MPC, was reported in the Economist on October 18, 2007, as saying, in relation to Northern Rock, that “the first duty of a central bank is to retain confidence in the banking system, especially at a time of illiquidity, and our central bank didn’t do that.”16

Sleeping in the Back Shop

Lord John McFall, chairman of the TSC, famously accused Sir John Gieve, the deputy governor at the Bank of England in charge of financial stability, at a hearing about Northern Rock on September 20, 2007 (Q6), of having a sleep in the back shop while a mugging was taking place in the front. The TSC was also particularly scathing about the governor of the Bank of England’s inaction, due to fears of moral hazard. This was economic theory speaking; it would surely have never been said by an experienced banker. It was time to act, not dither. Michael Fallon, at the time an MP and subsequently UK defense secretary, had it right when he suggested at the hearing that the problem was that the Bank of England failed the practical.

Alistair Darling (as reported in Darling 2011) rescued the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) in October 2008. At the time, it was the biggest bank in the world by assets and one of the largest companies in the world. He was told, on October 7, 2008, that if he didn’t rescue RBS, which couldn’t make a large payment, there was a significant chance that every cash machine and credit card in the world would stop working the following day. The next day, October 8, 2008, the MPC committee I was on had an emergency meeting and, in an unprecedented move, cut rates by 50 basis points in a coordinated easing in monetary policy with six other central banks—the Bank of Canada, the European Central Bank, the U.S. Federal Reserve, Sveriges Riksbank, the Swiss National Bank, and the Bank of Japan. When central banks act together in a surprise move there is good news and bad news. The good news was that they acted together and did something. The bad news was that something was obviously up, and the likelihood was that there had been a bank failure.

From September 2008 on the central banks eventually got it. They cut rates close to zero and started quantitative easing. The models were saying that there was a thing called the “zero lower bound” that interest rates couldn’t go below, so if you couldn’t lower the price of money then you had to raise the quantity. Only later did we discover that rates could go negative. Plus, the fiscal authorities threw the kitchen sink at the crisis by cutting taxes and offering cash for clunkers and fridges and lots of stimulus money. And it worked, and economies started to grow. Then the fiscal authorities around the world imposed austerity, which Mark Blyth called a “dangerous idea” (2015, 245), while Martin Wolf called it a large unforced error: “The fact that the economy grows in the end does not prove that needlessly weakening the recovery was a sound idea. This has been an unnecessarily protracted slump. It is good that recovery is here, though it is far too soon to tell its quality and durability. But this does not justify what remains a large unforced error.”17

Central banks were desperate to raise rates and continued to tell anyone who would listen that they were about to, although they didn’t because recovery was so tepid. The European Central Bank (ECB), though, did so twice in 2011 as did the Swedish central bank, which caused its economist, Deputy Governor Lars Svensson, to resign in 2013. Swift about-faces were to follow. By the end of 2018 the MPC had raised rates twice in ten years, once in November 2017 from 0.25 to 0.5 percent and then in August 2018 to 0.75 percent. Growth never did happen at the rate it had in past recoveries. It turned out that zero was not even the lower bound as several central banks, including the ECB, the Swiss, Swedish, and Japanese central banks, cut their rates to negative. It still remains unclear how low rates could go.

At the end of August 2008, I decided I was right, and that the UK economy was headed for disaster. I did an interview with Sumeet Desai and Matt Falloon of Reuters that got me into big trouble. I said that two million Britons might be out of work by Christmas and big cuts in interest rates were needed then and there to stop the economy from heading into a deep and prolonged slump. I take no pleasure in the fact that we now know officially from the ONS that unemployment hit two million in November 2008. I argued that the Bank of England could no longer be complacent because the economy was already shrinking, and a rate cut of more than 25 basis points was probably needed. I said that our forecast (figure 6.1A) was wishful thinking and that things could get much worse.

The fears that I have expressed over the last six months have started to come to fruition. I’ve obviously voted on quite a number of occasions now for small cuts but we need to act and we probably need to act in larger amounts than that. We need to actually get ahead of the game and it appears that we are now behind. We are going to see much more dramatic drops in output. The way to get out of it is to act, by interest rate cuts and fiscal stimulus and other things to try [to] help people who are hurt through this. Sitting by doing nothing is not going to get us out of this and hoping that a knight in shining armor will come and lift us out of this is optimistic in the extreme.18

The MPC meeting was the following Wednesday and Thursday, September 3 and 4, 2008. We would always meet to be briefed on the previous Friday, which was August 29, the day after my interview appeared. I had my hand slapped, which if it had been carried out by Margaret Thatcher would have been called a “severe hand-bagging,” about what I had said in the interview. But I made clear I was not impressed by the rest of the MPC’s inability to spot the greatest recession in a generation. I had nothing to apologize for.

At that meeting I voted for a rate cut of 50 basis points while the rest voted to leave rates at 5 percent, which they argued was necessary “if inflation was to be brought back to the target in the medium term. That would continue to balance the upside and downside risks to inflation appropriately.” In contrast this is what I said: “For one member, the prospects for UK demand had clearly worsened over the month, increasing substantially the downside risk to inflation in the medium term. There was no evidence that inflation expectations were pushing up nominal pay growth. The slowdown might be amplified by financial institutions’ responses to increased financial fragility. A significant undershooting of the inflation target, in the medium term, at a time when output and employment would be well below potential, risked damaging the credibility of the monetary framework.”19

Rates were cut by 50 basis points at the next meeting. They were cut by 150 basis points in November; 100 in December; and 50 in January, February, and March 2009 to 0.50 percent. Seventy-five billion pounds of asset purchases were made in March 2009 and a further £50 billion in May that I voted for. By May 2018 £435 billion of government bonds and £10 billion of corporate bonds were held by the MPC. Quantitative easing started at least a year too late.

The failures of Lehman Brothers, RBS, and Lloyds, the latter two of which were secretly rescued by the UK government, were the turning points. Things might well have been worse if the authorities hadn’t acted. In a CBS 60Minutes program on March 15, 2009, Ben Bernanke argued that if AIG had failed it would have brought down the financial system. On December 3, 2010, he was interviewed again on 60 Minutes and was asked about the counterfactual.

Scott Pelley: What would unemployment be today?

Ben Bernanke: Unemployment would be much, much higher. It might be something like it was in the Depression. Twenty-five percent. We saw what happened when one or two large financial firms came close to failure or to failure. Imagine if ten or twelve or fifteen firms had failed, which is where we almost were in the fall of 2008. It would have brought down the entire global financial system and it would have had enormous implications, very long-lasting implications for the global economy, not just the U.S. economy.

I got into even more trouble when I tried to explain what the counter-factual was in the UK. On September 24, 2009, I wrote in the New Statesman that “if spending cuts are made too early and the monetary and fiscal stimuli are withdrawn, unemployment could easily reach four million. If large numbers of public sector workers, perhaps as many as a million, are made redundant and there are substantial cuts in public spending in 2010, as proposed by some in the Conservative Party, five million unemployed or more is not inconceivable.”20 The word “if” here was crucial.

I was simply trying to understand the counterfactual—what the world would have looked like if the MPC hadn’t acted. In a speech on December 6, 2015, Mark Carney argued that the Bank of England estimated that unemployment would have been 1.5 million higher at its peak, of 2.5 million or so, if the MPC hadn’t acted.21 In 2018 Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson explained what happened in the fall of 2008: “What we were trying to do was to prevent Armageddon. We were looking at a situation where if we felt we had one more big institution go down, it would have taken the whole system down. We were focused on staving off disaster.”22

Trust in Economists, Rightly, Is Low

Economists and policymakers were looking at what was going on in entirely the wrong way. They were focused on what happened in the 1970s, as I will explain later, which was most unlikely to repeat, and on largely untested theoretical models that amounted to little more than mathematical mind games. Their best defense was that nobody could possibly have expected us to spot the biggest crisis in a generation. That wasn’t good enough, of course. We had experienced the Great Depression. The experts were just looking in the wrong places.

I went to a meeting of the Canadian Learned Societies in Newfoundland in May 1997 to present a paper. I arrived at the airport and asked the taxi driver to take me to the Learned Society meetings. He told me that the participants called them “the learneds” and that the locals had another name for the meetings and those who went to them: “the stupids.” I didn’t realize at the time what an important insight that was.23

The reputation of economists and other experts has taken a big hit. As the Queen said at the London School of Economics in November 2009 when she was opening the new Department of Economics, “Why did no one see this coming”? The answer of course was they were working on something else that was more important, which they weren’t.

A three-page response from the British Academy to the Queen in July 2009 signed by around thirty distinguished economists, economic journalists, and politicians didn’t help. In my view, the letter made it worse: “In summary, Your Majesty, the failure to foresee the timing, extent and severity of the crisis and to head it off, while it had many causes, was principally a failure of the collective imagination of many bright people, both in this country and internationally, to understand the risks to the system as a whole.”24

Ex—Bank of England deputy governor Charlie Bean astonishingly argued, in a speech in October 2010, that “no one should expect to be able to predict the timing and scale of these sorts of events with any precision.”25 I recall Gordon Brown, the British prime minister, saying that the UK government in September 2007 had simulated what would happen if a bank failed but not if the whole financial system came tumbling down. “We always liked to plan for any eventuality and so we thought it would be very useful to play through the scenario of a bank failure…. Would the fall of a bank or a building society raise systemic issues? Could we allow such a bank or building society to fail? “What was the point at which such a collapse became a threat to the entire system?” (2010, 17). He continued: “At the time the simulation was not set up to ask what might happen if a combination of banks might be in difficulty” (2010, 19).

Economics itself is in a sorry stated.26 It has overemphasized the importance of theory and “mathiness,” as former World Bank chief economist and 2018 Economics Nobel Laureate Paul Romer (2015) has argued. His claim is that economists have made use of mathematics principally to persuade or mislead rather than to clarify. I have a good deal of sympathy with his view that mathiness allows academic politics to masquerade as science. Romer is right that in the end, the test of a model is its “correspondence with the world.”27

In his presidential address to the American Economic Association in December 1970, Wassily Leontief argued that “in no other field of empirical inquiry has so massive and sophisticated a statistical machinery been used with such indifferent results” (1971, 3). Nothing much had changed four decades later.

Wolfgang Münchau has argued that the curse of our time is fake math. “Think of it,” he says, “as fake news for numerically literate intellectuals: it is the abuse of statistics and economic models to peddle one’s own political prejudice…. Fake maths has given us, the liberal establishment, the illusion of certainty.”28 He may well be right.

Thomas Piketty has argued that “to put it bluntly, the discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research and collaboration with other social sciences. Economists are all too often preoccupied with petty mathematical problems of interest only to themselves. This obsession with mathematics is an easy way of acquiring the appearance of scientificity without having to answer the more complex problems posed by the world we live in” (2014, 41). That is exactly what I address in this book: the complex problems posed by the world we live in, specifically in relation to jobs.

It is perhaps not surprising that macroeconomists missed the Great Recession. The profession had become complacent. In his 2003 presidential address to the American Economic Association, Bob Lucas denied the possibility of a Great Recession, arguing that “macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades” (2003, 1). It hadn’t. The view was that stabilization of output, even if possible, should not be a macroeconomic priority because the gains are trivially small. Future Fed chair Janet Yellen and George Akerlof (2006) countered by arguing there is a solid case for stabilization policy, which can produce non-negligible gains in welfare.

John Rapley has it right: “We should have read the warning signs. If history teaches us anything it’s that whenever economists feel certain they’ve found the holy grail of endless peace and prosperity, the end of the present regime is nigh…. No sooner do we persuade ourselves that the priesthood has finally broken the old curse than it comes back to haunt us all: pride always goes before a fall” (2017, 399). It sure does.

Economic Forecasting Is Broken

John Kenneth Galbraith once said that economic forecasting makes astrology look good. Ex-president of the Minnesota Federal Reserve and voting member of the FOMC Narayana Kocherlakota, now a professor at the University of Rochester, has argued that macroeconomic forecasting is still broken. Kocherlakota suggests that the point of forecasting is to get a sense of possible outcomes and allocate probabilities to them.29 The problem is the probabilities have been way off.

In December 2007, the Federal Reserve estimated that there was a less than 5 percent chance that the unemployment rate would be above 6 percent in two years. It eventually rose to 10 percent. Kocherlakota says he has seen little response from academics to fix the problem over the last decade. This, he suggests, matters as “the central bank remains set on raising interest rates because it sees downside risks, such as a sharp decline in growth and hiring, as being relatively small. But there are good reasons to worry that, just as in 2007, any model-based assessment of those risks is overly optimistic—and perhaps wildly so.”30

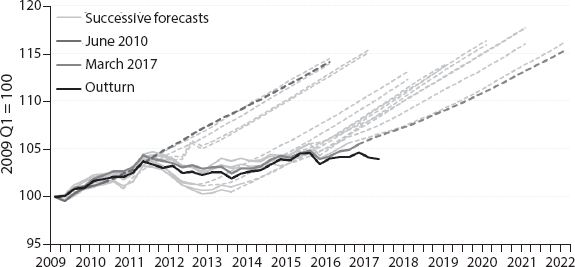

Many forecasters have simply assumed that what has come to be known as the productivity puzzle will simply vanish into the ether. For example, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which produces forecasts for the UK government, assumed that productivity growth would simply return to pre-recession levels. Their forecasts have been wildly inaccurate. Figure 6.2, taken from the OBR’s 2017 Forecast Evaluation Report, shows successive and essentially unchanging and inaccurate OBR productivity forecasts and the actual data. No wonder the public is skeptical of elites.

The black line in the figure shows the outcome over the period from 2009 through 2017 along with sixteen successive forecasts. Each forecast implausibly slopes up sharply, and all the forecasts are basically parallel to each other. Each of them forecasts an explosion of productivity growth, which never happened, but there was no learning and no change. The latest March 2017 report showed a very slight shallowing. Each assumed the productivity puzzle was solved when it wasn’t. How could they keep making the same mistake? How could they claim productivity was about to take off even though it hadn’t for ages and every one of their prior forecasts had been terrible?

Of interest is the timing of the collapse of productivity growth. This follows almost exactly from the introduction of austerity in the UK budget of June 2010. The changes took a little time to have an impact, so if we assume 2011 Q2 as a reasonable starting point for the effects of austerity, output per hour was 103.7, with 2009 = 100. By 2017 Q2 it was 103.9. Austerity killed productivity. The elites got it wrong but took no responsibility. There was no accountability for this abject failure. Nobody fired the forecasters. This is not unique to the UK. Both the U.S. Federal Reserve and the MPC’s forecasts were equally hopeless. Each continued to assume all would be well tomorrow, but tomorrow never came. We are now ten years into the crisis.

Figure 6.2. Successive OBR productivity forecasts (output per hour). Solid lines represent the outturn data that underpinned the forecasts at the time (the dashed lines). Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Forecast Evaluation Report, October 2017 chart 1, https://obr.uk/fer/forecast-evaluation-report-october-2017/.

In October 2017, in its Forecast Evaluation Report (FER), the OBR produced a mea culpa admitting it had been wrong all along; the productivity puzzle had not been solved and the UK economy was not set to mean revert to pre-recession levels: “One recurring theme in past FERs has been productivity falling short of our forecasts…. Our rationale for basing successive forecasts on an assumed pick-up in prospective productivity growth has been that the post-crisis period of weakness was likely to reflect a combination of temporary, albeit persistent, influences. And as those factors waned, so it seemed likely that productivity growth would return towards its long-run historical average.”31

And later: “While we continue to believe that there will be some recovery from the very weak productivity performance of recent years, the continued disappointing outturns, together with the likelihood that heightened uncertainty will continue to weigh on investment, means that we anticipate significantly reducing our assumption for potential productivity growth over the next five years in our forthcoming November 2017 forecast.”32

In January 2017 Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist and MPC voter, expressed his concerns about the state of economics. He said it was “a fair cop” that economists had missed the financial crisis.33 David Miles, who replaced me on the MPC, took a rather different view, arguing that to the extent that economics says anything about the timing of such events like the Great Recession it is that they are virtually impossible to predict.34 I don’t think so.

The State of Macro Is Bad

The paper mentioned in chapter 1, written by Olivier Blanchard (2009) just before the crash of Lehman Brothers that claimed the state of macroeconomics is “good,” made no mention of any real-world data and was seemingly unaware that almost every EU country and the United States had been in recession for several months. The paper argued that macroeconomics was going through a period of great progress and excitement: “A macroeconomic article today often follows strict, haiku-like rules. It starts from a general equilibrium structure, in which individuals maximize the expected present value of utility, firms maximize their value, and markets clear. Then, it introduces a twist, be it an imperfection or the closing of a particular set of markets, and works out the general equilibrium implications. It then performs a numerical simulation based on calibration, showing that the model performs well. It ends with a welfare assessment.”

I have no idea what “haiku-like” rules are or how they can help us understand how an economy works. The man on the Clapham omnibus would, rightly, likely think it was worthless mumbo-jumbo. I have been especially struck by claims celebrating that the practice of macroeconomics is firmly grounded in the principles of economic theory.35 It would have been much better if macroeconomics had been well grounded in the muddy waters of the data. Difficulties arise when a subject emphasizes theory over empirics. Theory is fine, but we need to test it against data from the real world to see if a theory fits the data and how well it works compared with competitors. Just like selling new cars. If economics is not what Arnold Harberger (1993) called an observational discipline, it is nothing. Macroeconomic theory has proved itself to be largely irrelevant.

I have a great deal of sympathy with Nobel Laureate Bob Solow’s view (2008) that because modern macro has paid very little rigorous attention to data there is essentially nothing in the empirical performance of these models that could come close to overcoming a modest skeptic. Hence, they shouldn’t be used for serious policy analysis. The problem was they were, and that contributed to the big mess in 2008.

In a recent blog post Russ Roberts, the host of the podcast Econ Talk, even goes as far as arguing that “most economics claims are really not verifiable or replicable.” He suggests that “economics provides the illusion of science, the veneer of mathematical certainty.”36 Adam Ozimek responded, noting that even when empirical economics doesn’t settle questions definitively or provide reliable point estimates, it narrows the scope of debate and rules out obviously wrong answers.37 Maybe.

Noah Smith goes further, arguing that the alternative to empiricism in economics is not agnostic humility but intuitionism—the idea that we can know about the world by thinking about how it works and that exposure to evidence will only pollute the truths that we divine from our own minds. And that’s something he argues—and I agree—that economists need to avoid.38 John Cochrane in response to Roberts argues that “PhD training in economics focuses on theory and statistical technique, and prepares you well to do academic research … PhD training really is vocational training to do research, not to advise public policy…. Actually we need more math.”39 That may be what economists do, but in the long run it isn’t sustainable as university presidents will soon realize it is better to hire folks working on pressing real-world issues, such as a cure for cancer. Economists need to do more empirical testing not less. Mathiness doesn’t do it. Economists have incentives to publish in top-tier journals rather than to solve real-world problems. But there is hope.

Famously, Ronald Coase in his Nobel Prize lecture argued that “inspiration is most likely to come through the stimulus provided by the patterns, puzzles, and anomalies revealed by the systematic gathering of data, particularly when the prime need is to break our existing habits of thought” (1992, 718).

In a recent column celebrating the award of the 2017 Sveriges Riksbank Nobel Economics prize to Richard Thaler, Robert Shiller, who won the prize in 2013, noted that there had been antagonism within the profession to the research agenda of the behavioral economists, which includes him. Shiller notes that “many in economics and finance still believe that the best way to describe human behavior is to eschew psychology and instead model human behavior as mathematical optimization by separate and relentlessly selfish individuals, subject to budget constraints.” Shiller notes that people have trouble resisting the impulse to spend a $10 bill they might find on the sidewalk; as a result of such mistakes they save too little for retirement. Shiller concludes persuasively that “economists need to know about such mistakes that people repeatedly make.”40 Amen to that. Fortunately trying to understand how the world actually works is on the rise and is increasingly an honorable estate. This is what I call the economics of walking about.

Mohammed El-Arian noted that even after the Great Recession hit the elites were lost and stuck in the irrelevant past: “Despite the enormity of the ongoing dislocations, many were still hostage to the conventional cyclical mindsets that had served policy making well for many decades—that is the notion that advanced economies follow business cycles around a rather robust and stable path. As such they wrongly believed that the sharp down-turn in 2008–9 would be followed by an elastic-band like rebound” (2016, 69).

Some had even convinced themselves, wrongly, that the housing bubble in the early 2000s was entirely sustainable. This time was different. In the words of ex—MPC member Sir Stephen Nickell, “There are good reasons for believing that the equilibrium ratio of house prices to earnings is currently well above the average ratio of house prices to earnings over the last two decades.”41 By July 2007 the house-price to earnings ratio in the UK reached a peak of 5.81, well above its long-run peak, and down it all came. It didn’t stop tumbling until April 2009. Things were supposed to be different this time around; the models said so. They didn’t.

Sir Charles Bean, also a member of the MPC, agreed that a higher house-price to earnings ratio compared to the past was likely sustainable as everything had changed. Sadly, it hadn’t.

An average house today costs about six times average annual earnings, whereas the historical multiple is somewhat below four. Now there are good reasons why house prices should have risen relative to earnings. The transition to a low inflation, low interest rate environment has shifted the real burden of repayments for a typical mortgage into the future, so making it easier initially for cash-strapped households to service a loan of a given size. Demographic and social developments mean the number of households has been rising, while until recently the rate of house building has been low. And disillusion with the performance of the stock market and concerns about the value of pension promises may have boosted the demand for property as a vehicle for retirement saving. Nevertheless, it is difficult to rationalize the full extent of the increase in house prices and it is likely that the ratio of house prices to earnings will probably continue to ease for a while, though a return to historical norms seems unlikely.42

It’s no wonder the public has become disillusioned with experts in general and economists in particular. The elites were stuck in the past.

A survey conducted in the UK by YouGov in April 2017 found that there is a big problem of trust in the opinions of economists, particularly among people who have not studied economics (55%), among older age groups (54% of 65+ age group), among residents of the North of England (44%), and among Leave voters in the EU referendum (54%). Half of the respondents thought that economists expressed views based on personal and political opinion rather than on verifiable data and analysis. When asked what economists do, nearly two-thirds of respondents chose forecasting. Only 26 percent saw economists advising government on policies and 33 percent on industry regulation. When asked to name economists in the public eye, only 16 percent were able to provide any names.

Intent on Repeating the Mistakes of the 1930s

Soon after the crisis economists recommended reckless and unnecessary austerity. Policymakers jumped on board, as it was a great opportunity to reduce the size of the state. Nothing much more. As Mark Blyth noted in 2013, “Much of Europe has been pursuing austerity consistently for the past four years. The results of the experiment are now in, and they are equally consistent: austerity doesn’t work…. The only surprise is that any of this should come as a surprise.” Blyth said it well: “Austerity now insanity later” (49). Austerity, Blyth argued, is a delusion. Austerity continues to be a delusion.

Ryan Cooper recently argued that during and immediately after the crisis, neoliberal and conservative forces attacked the Keynesian school of thought from multiple directions.

Stimulus couldn’t work because of some weird debt trigger condition, or because it would cause hyperinflation, or because unemployment was “structural,” or because of a “skills gap,” or because of adverse demographic trends.

Well going on 10 years later, the evidence is in: The anti-Keynesian forces have been proved conclusively mistaken on every single argument. Their refusal to pick up what amounted to a multiple-trillion-dollar bill sitting on the sidewalk is the greatest mistake of economic policy analysis since 1929 at least.43

In the UK, the Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne imposed austerity in June 2010 that crushed the fragile recovery. Osborne had backed all the spending plans of the previous Labour government and advocated for more deregulation. He blamed Labour for the global recession, arguing they failed to fix the roof as the sun was shining. This was the most important factor in the Brexit vote: the hurt who didn’t cause the recession but were the target of Tory austerity weren’t taking it lying down. By 2017 the dispossessed had more or less given up on many aspects of capitalism and at the same time support for a renationalization program for the commanding heights of the economy rose sharply. Even those with jobs in the UK over the previous decade have struggled to make ends meet as real wages in 2018 are still 5.5 percent below pre-recession levels.

In the June 2010 budget, the official forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility was that GDP growth would take off and the deficit would fall to zero by 2015–16. Growth disappointed and didn’t live up to the hyperbole. The debt-to-GDP ratio was forecast to be 67.4 percent (83.6%) in 2015–16 with average earnings growth of 4.4 percent (1.9%). The actual (bad) outcomes are in parentheses.44

When Margaret Thatcher resigned, it was reported she had made more trips as prime minister to the United States than she had to places north of the Watford Gap, eighty miles north of London. You can’t get there from here. People outside the big cities were hurting and the elites didn’t notice. They didn’t go there.

On March 23, 2011, George Osborne in his budget speech set out his plan for growth: “We want the words: ‘Made in Britain’, ‘Created in Britain’, ‘Designed in Britain’, ‘Invented in Britain’ to drive our nation forward. A Britain carried aloft by the march of the makers. That is how we will create jobs and support families. We have put fuel into the tank of the British economy.”45 Not exactly what happened.

Subsequently, the UK lost its AAA credit rating, and despite claims at the outset that the UK government would deliver a “march of the makers,” that didn’t happen, and manufacturing employment declined further. Public-sector pay freezes were imposed and public-sector employment fell sharply. Other governments around the world pursued tight fiscal policy, which meant that central banks were the only show in town. Low interest rates and many billions of asset purchases followed. House and equity prices rose but real wages fell.

The number of workforce jobs in UK manufacturing was 2.57 million in June 2010 compared to 2.72 million in September 2018. As a share of all workforce jobs in the UK, it fell from 8.2 percent in June 2010 to 7.7 percent in the latest data. Chancellor Osborne didn’t keep his promises. There has been no march of the makers, just a march of the unemployed ex-makers.

In the United States, manufacturing employment in January 2019 was 12.8 million, down from 14 million in January 2007. Manufacturing employment was 9.9 percent of total non-farm employment in December 2007 versus 8.5 percent in 2019. Coal-mining jobs are down over the same period by a third and in January 2019 there were 52,700 miners, up from 50,800 in January 2017.

Cut Government Budgets and Lay People Off until They Get Jobs

The slowness of recovery from the Great Recession in large part is explained by the misplaced imposition of reckless austerity. Populism was a response to the lack of decent jobs, especially outside the big cities. The white working class took the heat.

Austerity that came in 2009 meant reversing the stimulus that fiscal authorities had undertaken that had successfully turned downturn into recovery. Cash for fridges and old cars was stopped, tax reductions were reversed, and public spending was cut, including public investment, with disastrous consequences. These measures, just as Keynes expected, almost instantly stalled recovery. “Look after unemployment and the Budget will look after itself,” was John Maynard Keynes’s advice. This may not always be true but, as Lord Skidelsky, Keynes’s distinguished biographer, and I argued in an oped in the New Statesman in 2011, it is better than the coalition’s stance of: “Look after the Budget and unemployment will look after itself.”46 It didn’t.

The fact that austerity has never worked mattered not. It was a unique political opportunity for the right to reduce the size of the state and never mind the social and economic consequences. They did a reverse Robin Hood, taking from the poor and giving to the rich. I always found it hard to understand the view that you paid the rich more and that made them work harder and paid the poor less to make them work harder.

There was a widespread view among mostly left- leaning economists, largely ignored by mostly right-leaning policymakers, that austerity was a really bad idea in a slump. I wrote endless articles in my weekly columns in the Independent and the New Statesman declaring it was a really dumb idea that would hurt ordinary people and wouldn’t generate an expansionary fiscal expansion but rather a contractionary fiscal contraction, which is what happened. Nobody listened.

Economics Nobel Laureate Joe Stiglitz has noted, “Take the central issue of austerity: it has never worked. Herbert Hoover tried it and converted the 1929 stock market into the Great Depression. I saw it tried in East Asia, when I was the World Bank’s chief economist: downturns became recessions, recessions depressions. The austerity medicine weakened aggregate demand, lowering growth; it reduced demand for labour, lowering wages and pushing up inequality; and it damaged public services on which ordinary citizens depend. In the UK, sharp cuts to public investment do not merely weaken the country today, but also ensure it will be weaker in the future.”47

As the economic historian Barry Eichengreen noted, “After a brief period in 2008–9 when the analogy to the Great Depression was foremost in the minds of policy makers, and the priority was to stabilize the economy, the emphasis shifted. The priority now was to balance budgets. For central banks, it was preventing an outbreak of inflation, however chimerical. The shift occurred despite the fact that the recovery continued to disappoint. Rather than avoiding the mistakes of the 1930s, policy makers almost seemed intent on repeating them” (2015, 284).

Paul Krugman argued that austerity “was not at all grounded in conventional macroeconomic models. True, policy-makers were able to find some economists telling them what they wanted to hear, but the basic Hicksian approach that did pretty well over the whole period clearly said that depressed economies near the zero lower bound should not be engaging in fiscal contraction. Never mind, they did it anyway” (2018, 165).

As the Financial Times’ Martin Wolf noted, “Austerity has failed. It turned a nascent recovery into stagnation. That imposes huge and unnecessary costs, not just in the short run, but also in the long term: the costs of investments unmade, of businesses not started, of skills atrophied, and of hopes destroyed.”48

Harvard economist Alberto Alesina told the Austerians what they wanted to hear, that in the aftermath of the Great Recession, many OECD countries needed to reduce large public-sector deficits and debts. He claimed that “fiscal adjustments, even large ones, which reduce budget deficits, can be successful in reducing relatively quickly debt over GDP ratios without causing recessions. Fiscal adjustments based upon spending cuts are those with, by far, the highest chance of success” (2010, 15). That didn’t work out so well.

In the Mais lecture on February 24, 2010, called “A New Economic Model,” the soon to be Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, quoting work by Reinhart and Rogoff (2010), warned that “the latest research suggests that once debt reaches more than about 90% of GDP the risks of a large negative impact on long term growth become highly significant.”49 This was used as a justification in the UK and elsewhere for austerity.

It turns out that result was entirely false, as shown by University of Massachusetts graduate student Thomas Herndon. He came to talk to one of my classes at Dartmouth and showed the result arose because of a series of spreadsheet errors. Countries with high debt-to-GDP ratios were simply omitted from the calculations. When they were included the results completely disappeared.50 The 90 percent number was wrong. Mark Blyth (2013) has called this “Excelgate.”

Stephen Colbert was unmerciful in an episode of the Colbert Report on April 23, 2013, where he discussed the spreadsheet errors with Thomas Herndon as a special guest. Colbert succinctly summarized how austerity was supposed to work: “We have to keep cutting government budgets and laying off people until those people get jobs.” Funny but sad. The justification for all that austerity disappeared into the ether. And it was all down to a smart graduate student.

Alesina has now more or less gone back on his earlier findings where he concluded, for example, that “fiscal consolidations implemented mainly by raising taxes entail large output costs.” Alesina and coauthors punted on whether austerity was the right thing to do: “Our results however are mute on the question whether the countries we have studied did the right thing implementing fiscal austerity at the time they did” (2015, 1).

Simon Wren-Lewis argues that

the reason why economists like Alesina or Rogoff featured so much in the early discussion of austerity is not because they were influential, but because they were useful to provide some intellectual credibility to the policy that politicians of the right wanted to pursue. The influence of their work did not last long among academics, who now largely accept that there is no such thing as expansionary austerity, or some danger point for debt. In contrast, the damage done by austerity does not seem to have done the politicians who promoted it much harm, in part because most of the media will keep insisting that maybe these politicians were right, but mainly because they are still in power.51

The consequences of this lack of understanding of how the real world operates led to Western economies being unprepared for what was coming, especially because of their narrow focus on inflation. Of relevance here is Paul De Grauwe’s well-known comment that macro models were as useful as the line of defense France built on its borders with Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Germany in the 1930s.52 Macro models in central banks, he claimed, in the 2000s operated like a Maginot line. They were built to fight inflation, but that was the last war. They weren’t prepared to fight the new war against financial upheavals and recession. The macroeconomic models, De Grauwe suggests, do not provide central banks with the right tools to be successful. Mervyn King, in a speech on the tenth anniversary of the formation of the MPC, argued that “there is no more important challenge than keeping inflation and inflation expectations anchored on the target.”53 It turns out there was.

Lord Skidelsky argued in October 2008 that to understand how markets can generate their own hurricanes there was a need to return to John Maynard Keynes.54 He noted that over the past quarter century economists devoted their intellectual energy to proving that such disasters cannot happen. The models, Skidelsky noted, failed to take account of greed, ignorance, euphoria, panic, herd behavior, predation, financial skullduggery, and politics—the forces that drive boom-bust cycles. The Big Short couldn’t possibly be true. This meant that mainstream theory had absolutely no explanation for why things had gone so horribly wrong. Bubbles apparently hardly ever happen, but they do. The Financial Times columnist Wolfgang Münchau went as far as to argue that macroeconomists are no longer considered experts on the macroeconomy!55

Simon Wren-Lewis has claimed, though, that some bits of macroeconomic theory in some ways have had a good crisis in that Keynesian macro theory says not to worry about borrowing in a recession as interest rates will remain low and they have.56 Keynes, the Master, was right.57 New Keynesian theory said that creating lots of money via quantitative easing would cause runaway inflation and it hasn’t. Macro theory, Simon suggests, predicts that the move to austerity would delay and weaken the recovery, and it did. He probably has a point. There were winners and losers.

Economists as Engineers, Dentists, and Plumbers: There Is Hope!

Greg Mankiw argued that the problem that gave birth to macroeconomics was the Great Depression. God, he suggested, put macroeconomists on earth not to propose and test elegant theories but to solve practical problems, which were not modest in dimension. He suggested that economists needed to be more like engineers.

My premise is that the field has evolved through the efforts of two types of macroeconomist—those who understand the field as a type of engineering and those who would like it to be more of a science. Engineers are, first and foremost, problem-solvers. By contrast, the goal of scientists is to understand how the world works. The research emphasis of macroeconomists has varied over time between these two motives. While the early macroeconomists were engineers trying to solve practical problems, the macroeconomists of the past several decades have been more interested in developing analytic tools and establishing theoretical principles. These tools and principles, however, have been slow to find their way into applications. As the field of macroeconomics has evolved, one recurrent theme is the interaction—sometimes productive and sometimes not—between the scientists and the engineers. The substantial disconnect between the science and engineering of macroeconomics should be a humbling fact for all of us working in the field. (2006, 29–30)

Very good. Esther Duflo (2017) later argued that economists should seriously engage with plumbing! She suggests as economists increasingly help governments design new policies and regulations, they take on an added responsibility to engage with the details of policymaking and, in doing so, to adopt the mind-set of a plumber. Plumbers, Duflo suggests, try to predict as well as possible what may work in the real world, mindful that tinkering and adjusting will be necessary since our models give us very little theoretical guidance on what (and how) details will matter. Economists as engineers and plumbers seems fine to me.

Larry Summers, ex–Harvard president and Treasury secretary, summarized it so well: “Good empirical evidence tells its story regardless of the precise way in which it is analyzed. In large part, it is its simplicity that makes it persuasive. Physicists do not compete to find more elaborate ways to observe falling apples. Instead they have made progress because theory has sought inspiration from a wide range of empirical phenomena. Macroeconomics could progress in the same way. But progress is unlikely, as long as macroeconomists require the armor of a stochastic pseudo-world before doing battle with evidence from the real one” (1991, 146).58

Olivier Blanchard (2016) argued that the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models used by macroeconomists that failed so badly in the Great Recession are improvable. Economics Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman responded to this by saying what makes a modeling approach truly useful is when it offers “surprising successful predictions.” He asks, “Were there any interesting predictions from DSGE models that were validated by events?” and answers his own question: “If there were, I’m not aware of it.” He concludes, “At the very least we should admit to ourselves how very sad the whole story has become.”59

In contrast, Reis argues, “Current macroeconomic research is not mindless DSGE modeling filled with ridiculous assumptions and oblivious of data. Rather, young macroeconomists are doing vibrant, varied, and exciting work, getting jobs, and being published,” but, he concedes, “macroeconomics informs economic policy only moderately” (2017, 132). There is the rub. It didn’t in 2008 and hasn’t since. DSGE models look awfully like mindless modeling to this empirical labor economist.

Joe Stiglitz has suggested, rightly, that the most important function of any macro model is to provide insights into the deep downturns that have occurred repeatedly and what should be done in response. He suggests, “The DSGE models fail in explaining these major downturns, including the source of the perturbation in the economy which gives rise to them; why shocks, which the system (in these models) should have been able to absorb, get amplified with such serious consequences; and why they persist, i.e., why the economy does not quickly return to full employment, as one would expect to occur in an equilibrium model. These are not minor failings, but rather go to the root of the deficiencies in the model” (2018, 71). This is a devastating critique of the state of macroeconomic modeling. Krugman went as far as to argue that “while there was a failure to forecast the crisis, it did not come down to a lack of understanding of possible mechanisms, or of a lack of data, but rather through a lack of attention to the right data” (2018, 156).

Who Needs Bloody Experts?

A UK government minister even compared economists to Nazis. Michael Gove, UK secretary of state for justice, made clear in 2016 why voters in the EU referendum should not listen to the economic organizations warning about the impact of a Leave vote. “I think the key thing here is to interrogate the assumptions that are made and to ask if these arguments are good,” Mr. Gove said during an interview with LBC Radio. “We have to be careful about historical comparisons, but Albert Einstein during the 1930s was denounced by the German authorities for being wrong and his theories were denounced and one of the reasons of course he was denounced was because he was Jewish. They got 100 German scientists in the pay of the government to say that he was wrong, and Einstein said ‘Look, if I was wrong, one would have been enough.’”60

Aditya Chakrabortty, senior economics editor at the Guardian, was right when he told me in private communication that politics has now become the art of promising the impossible. Aditya suggests we are now in the world of fantasy politics, which allows politicians to say you shouldn’t believe experts. Michiko Kakutani summarizes the strategy employed by the populist politicians in regard to policies on, for example, climate science or gun control and in the UK the impact of Brexit that run counter to expert evaluation and the polls: “Dig up a handful of professionals to refute established science or argue that more research is needed; turn these false arguments into talking points and repeat them over and over and assail the reputations of the genuine scientists on the other side” (2018, 74–75). As Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda, noted, “A lie told once remains a lie, but a lie told a thousand times becomes the truth.”

The experts said that the banks were rock solid, wages were going to rise, the economy was going to grow, austerity would work beautifully, and the deficit would be paid off tomorrow. When none of that happened, ordinary folk held up their hands and ended up believing populist messages that offered hope. The failure of the elites played a big part in the rise of fantasy politics. All of this hurt those most in need.

The experts also said that Donald Trump wasn’t going to win and that the British people would not vote for Brexit. My friend Sir Steve Smith, who is the excellent vice-chancellor of Exeter University, whose field is international relations, told me with economists failing to spot the Great Recession there were similarities in that experts in his field failed to spot the fall of the Berlin Wall! The experts did miss the big one though. Why did no one see this coming? They were working on something else.