CHAPTER 10

Disastrous Cries for Help

On every major issue affecting this country, the people are right, and the governing elite are wrong.

DONALD TRUMP1

The populist movements around the world are a direct result of the inadequate response by the elites to the Great Recession. They were cries for help. Tis is not unique to the UK or the United States; these are the first manifestations of the failures of the elites to notice what was happening outside the big cities. Living standards in the UK haven’t risen for years and many good jobs have disappeared. We still seem to be in the long, dragging conditions of semi-slump. What we have seen is a silent, largely peaceful revolution: a silent riot in the United States, France, Italy, and elsewhere. I had expected that, as in previous recessions, there would be trouble on the streets, but that hasn’t happened until recently. There were riots in the UK and Sweden in 2011 that were quickly snuffed out by the authorities. All of that changed in the autumn of 2018, with widespread protests in France against fuel taxes, which led to riots in Paris, which then spread to Belgium and the Netherlands.

There was a broad degree of commonality among those who voted for Trump, Brexit, and Frexit. The left-behinds had been put upon for too long. In the UK support for Brexit was high for those on low incomes and among the least educated. Three-quarters of those without qualifications versus a quarter with a postgraduate degree voted for Brexit. The young, minorities, and immigrants and those who lived in big cities voted against Brexit. The left-behinds voted for Trump, Brexit, and more.

Trump: He Can Create Change

According to a CNN exit poll, 51 percent of respondents who had a high school diploma or less or some college voted for Trump, compared with 44 percent of college graduates and 37 percent of those with a postgraduate degree.2 Fifty-seven percent of whites versus 8 percent of blacks and 28 percent of Latinos voted for Trump. Thirty-six percent of those aged 18–29 and 41 percent of those aged 30–44 voted for Trump. In contrast, 52 percent of those 45 and above did. People living in the rural heartland voted for Trump. The less-educated, low-income, non-immigrant folks also voted for Frexit. The right-wing nationalist in France, Marine Le Pen, fared better in areas with a greater concentration of people without a high school degree.

I voted for Donald Trump because he can create change for our country, economy, and world.

—Erin Keefe, 22 years old, Manchester, N.H.3

After all the pain and suffering I documented in chapter 9 there was always going to be a backlash. The Clinton campaign clearly underestimated the hurt being felt by white non-Hispanics in the rust-belt states. It is no accident, in my view, that West Virginia, the unhappiest state, with the highest drug-poisoning death rate, was the state that showed the biggest increase in the Republican vote compared to the increase seen in the 2012 presidential election. Ohio was close behind.

Monessen, Pennsylvania, is a faded steel town of 7,500 people about thirty miles south of Pittsburgh. Trump visited there in June 2016. Monessen’s population has dropped from 18,000 in 1960 to 7,500 in 2015, and the city’s major steel mill closed in the 1980s. The city has 700 registered Republicans, but Trump won by 1,221 votes. Mayor Lou Mavrakis in an interview with PRI’s The World’s Jason Margolis said, “What does our community look like? It looks like Beirut. If ISIS were to come here, they would keep on going because they’d say somebody already bombed us. And that’s the way all the communities look that had steel mines up and down the Mon Valley.”4

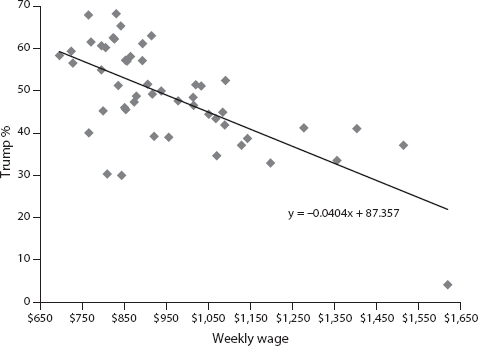

Figure 10.1. Trump % of vote by state and QCEW weekly wage.

In an earlier interview with Margolis, Mayor Mavrakis said that he knew that Trump couldn’t bring back the steel mills but hoped he might be able to revive manufacturing. In the same interview long-time Democrat Billy Hans, Margolis reported, had already made up his mind: “I like Trump.” The 58-year-old building contractor had never voted for a Republican for president, but he thought Trump could bring some jobs back to the area. “It’s not going to be easy, but I think he can bring some back. He’s got to get companies to invest.”5

John Golomb, 65, a retired steelworker and a lifelong Democrat, explained why he voted for Donald Trump. “We want our jobs back,” said Mr. Golomb, who lives in Monessen. He worked for thirty-five years in mills with 2,400-degree blast furnaces that made steel used to lay railroads and build cars. But the biggest mill shut three decades ago, and Monessen has been slowly dying ever since. “They forgot us. We’re hoping he keeps some percentage of the promises of bringing coal and iron back to this country.”6

Figure 10.1 shows that the Trump vote is negatively correlated with average weekly wages. I mapped onto the state voting data the Quarterly Census of Employment Wages (QCEW) for 2015 from the BLS. The best-fit line slopes downward. States with lower wages were more likely to vote Trump.

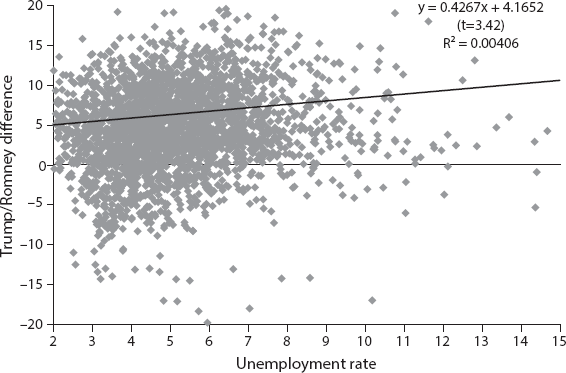

Figure 10.2. Difference between Trump-Romney share and the 2016 unemployment rate.

Figure 10.2 plots the Trump-Romney difference in the unemployment rate. The higher the unemployment rate the higher the difference. Places that were hurting voted for Trump. I also found that the Trump-Romney difference was positively correlated with the heavy drinking rate and obesity rates, and negatively correlated with life-expectancy rates. By state the Trump vote is positively correlated with the suicide rate and the incidence of bad mental health. Places that were hurting the most voted for Trump. I report below that disadvantaged communities, on a host of measures, in the UK went for Brexit and in France for Le Pen.

Nate Silver (2016) took a list of all 981 U.S. counties with 50,000 or more people based on data from the American Community Survey, and sorted it by the share of the population age 25 and over that had completed at least a four-year college degree. He found that Hillary Clinton improved on President Obama’s 2012 performance in 48 of the country’s 50 most well-educated counties. And on average, she improved on Obama’s margin of victory in these countries by almost 9 percentage points, even though Obama had done well in them to begin with. The list includes major cities, like San Francisco, and counties that host college towns, like Washtenaw, Michigan, where the University of Michigan is located.

Silver then looked at the 50 least-educated counties. Clinton lost ground relative to Obama in 47 of the 50 counties—she did an average of 11 percentage points worse, in fact. Silver notes that these are the places that won Donald Trump the presidency, especially given that a fair number of them are in swing states such as Ohio and North Carolina. Trump improved on Mitt Romney’s margin by more than 30 points in Ashtabula County, Ohio, for example, an industrial county along Lake Erie that hadn’t voted Republican since 1984.

And this is also a reasonably diverse list of counties. While some of them are poor, a few others—such as Bullitt County, Kentucky, and Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana—have average incomes. There’s also some racial diversity on the list: Starr County, Texas, is 96 percent Hispanic, for example, and Clinton underperformed Obama there (although she still won it by a large margin). Edgecombe County, North Carolina, is 57 percent black and saw a shift toward Trump.

Silver argues that there are several competing hypotheses that are compatible with this evidence, some of which will be favored by conservatives and some by liberals:

• Education levels may be a proxy for cultural hegemony. Academia, the news media, and the arts and entertainment sectors are increasingly dominated by people with a liberal, multicultural worldview, and jobs in these sectors also almost always require college degrees. Trump’s campaign may have represented a backlash against these cultural elites.

• Educational attainment may be a better indicator of long-term economic well-being than household incomes. Unionized jobs in the auto industry often pay reasonably well, even if they don’t require college degrees, for instance, but they’re also potentially at risk of being shipped overseas or automated.

• Education levels probably have some relationship with racial resentment, although the causality isn’t clear. The act of having attended college itself may be important, insofar as colleges and universities are often more diverse places than students’ hometowns.

• Education levels have strong relationships with media-consumption habits, which may have been instrumental in deciding people’s votes, especially given the overall decline in trust in the news media.

• Trump’s approach to the campaign—relying on emotional appeals while glossing over policy details—may have resonated more among people with lower education levels as compared with Clinton’s “wonkier and more cerebral” approach.

White, less-educated, low-income people over the age of 45 at the individual level are the key characteristics. Where they lived matters too. The poorer the county the higher the probability they voted for Trump. These are precisely the characteristics of the people that I documented were in pain in the previous chapter.

But the empty promises keep on coming.

Brexit: We’ve Been Neglected So Long

At the time of this writing, three weeks before the March 29, 2019, deadline for Brexit, nobody has the faintest idea what form Brexit might take, or when, or even if, it will happen at all. There is still no credible deal that the UK parliament will accept, and a second vote seems possible.

A new study has examined subjective well-being around the time of the June 2016 Brexit vote and found short-lived impacts on well-being.7 Elation on the part of the Leavers was roughly canceled out by the huge disappointment on the part of the Remainers, but each of these effects was short-lived. The authors found that those reporting a preference for leaving the EU were less satisfied with life pre-referendum. At the individual level, the referendum outcome produced a windfall satisfaction gain among Leavers compared to Remainers that lasted for only three months, a well-being effect of the same size as around 20 percent of annual incomes. The initial positive subjective well-being effect of the Brexit vote, the authors found, was particularly pronounced for male and older respondents who reported a preference for leaving the EU. However, adaptation to the Brexit result was short-lived, both for those who preferred continued EU membership and for those who did not. The Brexit vote did not have a permanent impact on well-being.

In 1937 George Orwell published The Road to Wigan Pier, which documented the hardships in the West Midlands, Lancashire, and Yorkshire. Wigan is an old coal and manufacturing town in Lancashire, which has traditionally returned a Labour Party candidate for the last hundred years. It is hurting again. Wigan no longer has any coal mines.

Andrew Higgins in the New York Times reported on his interviews with a Wigan resident, Colin Hewlett, age 61, shortly after the Brexit vote. Hewlett said, “I don’t think a lot will change. But we have to give it a chance.” Life, he said, has “gone to the dogs. I don’t like people telling us what to do from miles away.” In a period of three years, Mr. Hewlett explained, his take-home pay had crashed from more than $665 a week to just $318. Worse, he added, is that his previously secure full-time employment contract had morphed into a “zero-hours contract,” under which his employer decides how much he works and how much it pays him depending on what it needs on any particular day. “It is basically slave labor,” Mr. Hewlett said. He complained that an influx of eager workers from Eastern Europe meant that employers now had no incentive to offer a fixed contract or more than the minimum wage for menial work.8 In the EU referendum, Wigan voted to leave by a 64 to 36 percent margin.

The surprise is there have been so few riots. Major riots did break out in England in 2011, which spread fast around the country. The authorities acted swiftly, and they have not been repeated. There were also smaller incidents in Sweden in 2010 and 2013. In the United States, they have been small, localized mostly in black inner-city neighborhoods in response to shootings of young black men by police.

There have been no riots in Austria, Italy, or the Netherlands as far as I can tell. In 2011, rioting broke out in England between August 6 and 11 in several London boroughs and spread quickly to several cities and towns across England. It involved looting, arson, and deployment of large numbers of police and resulted in the death of five people. Disturbances began on August 6 after a protest in the London borough of Tottenham, following the death of a local man who was shot by police on August 4. Several violent clashes with police ensued, along with the destruction of police vehicles, a double-decker bus, and many homes and businesses. Rioting spread to at least ten other London boroughs and then on to the English towns of Birmingham, Coventry, Leicester, Derby, Wolverhampton, Nottingham, West Bromwich, Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester, and Salford. More than 3,000 arrests were made, and more than 1,000 people were issued criminal charges for various offenses related to the riots. An estimated £200 million worth of property damage was incurred. The authorities came down hard on protestors and there have been no subsequent riots. The contagion was stopped, at least for a while.

But rioting has recently broken out in France and has spread to Belgium and the Netherlands. Anti-government gilet jaune (yellow vest) demonstrations over rising fuel taxes turned violent in Paris on four successive weekends in November and December 2018 and sent shock waves around the world. Stores were looted, masked men burned barricades, dozens of luxury cars were burned, buildings were set on fire, and anti-Macron graffiti was smeared on the Arc de Triomphe.9 At the time of writing there are further planned demonstrations. In Brussels, several hundred protesters gathered at the beginning of December. Police barricaded off the district where the European Union buildings are located and prevented traffic circling in the area. Clashes were reported and 70 arrests were reported. In the Netherlands, about 100 protesters gathered in a peaceful demonstration outside the Dutch parliament in The Hague and at least two protesters were detained in central Amsterdam.10 I recall speaking with someone from the ILO who told me that the big surprise in the period since 2008 was how few riots there had been. That seems to be changing fast. Riots are a function of hopelessness. Kim Willsher, the Guardian’s Paris correspondent, reported that one young male gilet jaune from the Auvergne in central France told her, “We’re here for many reasons but basically because we’re fed up. Everyone’s fed up.”11 In response President Macron announced “concrete measures” from January 1, including increasing the minimum wage by €100 (£90) a month. Overtime would be exempt from tax and social charges, and a planned tax on pensions under €2,000 a month would be canceled.12 All employers “who can” were asked to give workers a tax-free bonus at the end of the year. Maybe too little too late; only time will tell.

On June 23, 2016, the British people went to the polls to vote in the EU referendum. They were asked a simple question: “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?” Data from Google Trends show that the number of searches for “what is the EU” and “what is Brexit” started climbing across Britain late into the night on June 23, the day of the vote. The question “what is the EU?” spiked in popularity across all parts of the UK, in this order: Northern Ireland, Wales, England, Scotland.13

After the Brexit vote Faisal Islam, a reporter for Sky TV, went to Sunderland, home to a large Nissan car plant, to talk to voters. At the Colliery Tavern, he talked with the landlord, John Snaith, who was a Leave voter. Snaith said it was a protest. “Voters voted because we’ve been neglected so long. They thought this is a chance for them to hear our voice.”14 After the Brexit vote Nissan threatened to close the factory in case of a no-deal.

Wales voted overwhelmingly for Brexit. Seventeen of Wales’s 22 local authorities voted Leave. Torfaen voted nearly 60 percent to 40 percent to leave the EU. My friend Aditya Chakrabortty from the Guardian visited Torfaen after the Brexit vote and noted how bad things were. “On a typical weekday, the indoor market is a desert. Those bits of the high street that aren’t to let are betting parlours, vaping dens, and charity shops: the standard parade for hollowed-out towns across Britain. The reason isn’t hard to fathom: the mines shut down decades back; the factories have pretty much disappeared. Those big employers still left aren’t big employers anymore. One of the staff at BAE tells me that when he joined in 1982, it had 2,500 workers on its shopfloor; now, he reckons, it has 120. Swaths of Pontypool and the surrounding region of Torfaen now rank among the poorest in all of Britain. In one of the housing developments in Trevethin, 75% of all children under age four are raised in poverty.”15

Boston, Lincolnshire, had the highest out vote in the UK. Immigration rose by 460 percent between 2004 and 2014, and immigrants are now 14 percent of the population. This was mostly due to East Europeans coming to work in low-paying jobs in the fields or in processing factories. James Pickard of the Financial Times interviewed Andrew Matson, procurement director of TH Clements, a supplier of vegetables. Matson warned that without East European migrants that make up half his seasonal workforce, he would have to pay higher wages, which would have to be passed on to supermarkets and ultimately to the consumer: “A pack of broccoli is 49p, five years ago it was 99p. You’ve not had deflation like that anywhere else. That’ll have to change.” Pickard also reported that a Lithuanian man asked why English people did not seem to like foreigners. “They complain about us. But why they not do the work?”16

Seaside towns that are in decline because of cheap air fares to the Mediterranean mostly voted for Brexit with two major exceptions, Brighton and Hove—where I was born—which voted Remain. The main reason for their decline is that British tourists left for warmer climes when cheap flights became available. The Leave vote percentages were as follows: Blackpool (68%); Bournemouth (55%); Eastbourne (57%); Great Yarmouth (72%); Hastings (55%); Isle of Whyte (62%); Southend-on-Sea (58%); and Torbay (63%).

The Centre for Social Justice reported that, of the twenty neighborhoods across the UK with the highest levels of working-age people on out-of-work benefits, seven are in coastal towns. In one part of Rhyl, a seaside town in Wales, two-thirds of working-age people are dependent on out-of-work benefits. Coastal towns are among the most educationally deprived in the whole country. Some 41 percent of adults in Clacton have no qualifications, almost double the national average for England and Wales. Of the ten wards in England and Wales with the highest rates of teenage pregnancy, four are in seaside towns. The Blackpool local authority has the highest rate of children in care in the whole of England—150 per 10,000 people, which far exceeds the English average of 59.

The Centre for Social Justice (2016) examined in detail five coastal towns: Rhyl, Margate, Clacton-on-Sea, Blackpool, and Great Yarmouth. The proportion of working-age people on out-of-work benefits in the five towns ranged from 19 percent to 25 percent against a national figure of 11.5 percent. They concluded:

Whilst each town has its own particular problems a recurring theme has been that of poverty attracting poverty. As employment has dried up so house prices have fallen and so less economically active people—such as single-parent families and pensioners—have moved in, seeking cheaper accommodation and living costs. Similarly, vulnerable people—such as children in care and ex-offenders—have been moved in as authorities take advantage of low-cost housing as large properties have been chopped into houses in multiple occupation. Parts of these towns have become dumping grounds, further depressing the desirability of such areas and so perpetuating the cycle.

Helen Pidd interviewed residents of Blackpool in the English North West, just north of Liverpool.17 Four comments were particularly colorful.

Matthew Hodgkinson, a 19-year-old chef and trainee aerospace engineer, said he voted out for economic reasons: “It was because of the money we pay to stay in the EU, which I thought should stay in Britain. We could spend it on housing and healthcare—the NHS is close to collapsing.”

Josie Crooks, a 19-year-old student and waitress, said she thought Brexit was worth the risk. “I wasn’t sure which way to vote, even though I read a lot about it. In the end I thought: if we leave it’s not going to be the end of the world. You’ve got to take the chance.”

James Cross, a 39-year-old from Blackpool, argued, “Now that the result is in, the government should roll their sleeves up and make the best of it. They will have to rally around and get together. There’s no point moaning. The powers that be will have to just get it sorted and crack on.” There hasn’t been much cracking on.

Sonia Chatterjee, 64, who has lived in Blackpool for forty years, said, “The EU has been good for us and we benefited from it but I just want our country back. We voted to go out. What’s it got to do with them? We had a vote so why does parliament have to interfere? … I’m not fearful (Brexit won’t happen) but I wouldn’t put it past any of them—you never know what’s going to happen with lawyers with politicians.”18

After the Brexit vote, discontent was expressed by others in Blackpool who wanted leave to happen quickly. “I think they (the government) need to get a grip and get on with it,” said retail manager Emma Jones, 40. “In June, we already voted to leave. There shouldn’t be any laws or anything like that. We should just go ahead with it,” said postman Dave Hudson, 41. “I don’t think there are going to be any riots if it doesn’t happen, but people will get impatient. For me it’s got to be done proper, you can’t just rush it.”

The New York Times reported in August 2016 that there were great hopes in Blackpool that Brexit would turn the town around because of an increase in the number of Britons who were choosing not to vacation abroad because of the fall in the pound. “We don’t care much for Europe here. We don’t need it,” the paper reported that James Martin said as he walked against the wind on the blustery seafront. “We’re self-sufficient, pretty much.”19 Probably not.

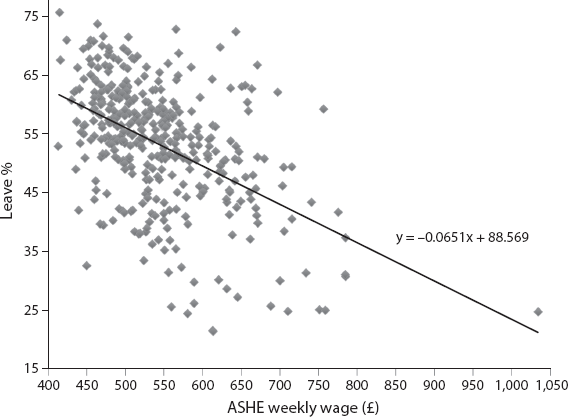

Figure 10.3, following the work of Bell and Machin (2016), plots the Leave vote by county against the annual ASHE weekly earnings estimates.20 It shows a strong negative slope, with the outlier to the far right, the City of London. Counties with higher pay were more likely to vote Remain. Counties with lower pay were more likely to vote Leave.

There are also significant positive relationships between voting to leave and the smoking rate (not reported), the obesity rate, and the suicide rate. The poorer an area, the greater its overall dependence on welfare benefits. High dependency on welfare benefits in a county, just like a higher unemployment rate, raises the prospect an individual would vote to leave. The poorer the health in an area, the higher the likelihood of a Leave vote. Low-wage areas also voted for Leave.

Figure 10.3. Leave % by ASHE gross weekly wage by UK county.

Interestingly, where the Leave vote was highest by region, pay levels were lowest, as measured by the percent earning below two-thirds of the median wage and the percentage of workers earning less than the living wage. Data from the Social Mobility Commission (2016) and the Resolution Foundation show the East Midlands, West Midlands, Wales, and Yorkshire had the lowest pay levels, all of whom voted to Leave.

Sasha Becker, who was a colleague of mine at the University of Stirling and is now at the University of Warwick, also found that the 2016 Brexit referendum result is tightly correlated with previous election results for the UK Independence Party, as well as those of the extreme right-wing British National Party (Becker, Fetzer, and Novy 2016). Becker and his colleagues found that fundamental characteristics of the voting population were key drivers of the Vote Leave share, especially their age and education profiles, the historical importance of manufacturing employment, and low income and high unemployment. Migration was relevant only as it pertained to Eastern European countries, not older EU states or non-EU countries. The severity of fiscal cuts, which largely reflect weak fundamentals, they found, were also associated with Vote Leave. They also obtained similar findings at the much finer level of wards within cities.

Importantly, Becker and coauthors found areas with a strong tradition of manufacturing employment were more likely to vote Leave, as well as areas with relatively low pay and high unemployment. They also found supporting evidence that the growth rate of migrants from the twelve EU accession countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 is linked to the Vote Leave share.

In addition, the quality of public service provision is systematically related to the Vote Leave share. Fiscal cuts in the context of the recent UK austerity program were strongly associated with a higher Vote Leave share. Alan Manning, a colleague of mine from LSE days, also examined Brexit votes by county and found that changes in the industrial structure of the area are important: falls in employment in heavy industry and the public sector between 1981 and 2011 are both related to a greater Leave vote (Langella and Manning 2016).

Kaufmann (2016) has argued that culture and personality, not material circumstances, separate Leave and Remain voters. He finds correlations between voting Leave and authoritarianism. He argues that among white British respondents, “there is almost no statistically significant difference in EU vote intention between rich and poor.” By contrast, he notes, the probability of voting Brexit rises from around 20 percent for those most opposed to the death penalty to 70 percent for those most in favor. The link with authoritarian views may be right, but as I will show there are strong and statistically significant differences between rich and poor. The rich voted to Remain; the poor voted for Brexit.

Clarke and Whittaker (2016) found cultural and geographical factors play a key role in whether people voted for Leave or Remain; feelings of cohesion within the local area mattered. This looks like culture wars again. Goodwin and Heath (2016b) argue that income and poverty do seem to matter: “Groups of voters who have been pushed to the margins of our society, live on low incomes and lack the skills that are required to adapt and prosper amid a post-industrial and global economy, were more likely than others to endorse Brexit.” They also found that the left-behind groups faced a “double whammy”: “While they are being marginalised because of their lack of skills and educational qualifications this disadvantage is then being entrenched by a lack of opportunities within their local areas to get ahead and overcome their own disadvantage.”

Ford and Goodwin have offered important insights about the intergenerational divide in views in the UK toward Europe and immigration. Their explanation resonates as it seems to explain the rise in populism elsewhere too.

The voters of the 1950s and 1960s, most of whom grew up amidst economic depression and war, prized “material” values, like basic economic security and social stability. In sharp contrast, their children and grandchildren take such things for granted and, instead, focus on “post-material” values like liberty, human rights, and environmental protection…. Younger voters, who have grown up and prospered in a more mobile and interconnected world, tend to have weaker attachments to their nation of birth, a thinner and more instrumental sense of what national identity means, a greater openness to immigration, and a greater acceptance of ethnic diversity. (2014, 156)

The Left-Behinds Voted for Le Pen

In an intriguing essay, Christopher Caldwell suggests that for those cut off from France’s new-economy citadels, the misfortunes are serious. He claims they’re stuck economically. He points out that three years after finishing their studies, three-quarters of French university graduates are living on their own; by contrast, three-quarters of their contemporaries without university degrees still live with their parents.

Caldwell notes that the left-behinds are dying early. In January 2016, the national statistical institute INSEE announced that life expectancy had fallen for both sexes in France for the first time since World War II, and he suggests that the native French working class is driving the decline: “Unlike their parents in Cold War France, the excluded have lost faith in efforts to distribute society’s goods more equitably.”21

Another report found that countries with recent populist movements tend to have a combination of low trust in government and low expectations of their future lives.22 Gallup terms those who lack confidence in their national government as “disaffected” and those who rate their lives on the same footing or worse in relation to their current lives as “discouraged.” France and the UK rank in the top ten EU countries with the highest percentage of disaffected and discouraged residents.

Mark Lilla has argued that “economic stagnation, political stalemate, rising right-wing populism—this has been France’s condition for a decade or more.”23 France had not been doing well, especially on the jobs front. In February 2017, the unemployment rate in France was 10 percent. For those aged 15–24 it was 23 percent. Long-term unemployment has risen from 35 percent of unemployment in 2009 to 44 percent in 2016. Underemployment rates in France are high. In 2015, 6.5 percent of all employment was made up of part-time workers who wanted full-time jobs. This compares with an average for the euro area of 4.6 percent and 5.6 percent in the UK.

Using two Eurobarometers, the regular surveys conducted by the European Commission, in 2010 and 2016, I have calculated whether respondents have had difficulties paying their bills most of the time, from time to time, or never. The percent saying most of the time in 2016 was especially high in France at 14 percent, up from 8 percent in 2010. In October 2016 respondents in the Eurobarometer #86.1 were asked if they thought the country was headed in the wrong or right direction. It is notable that 86 percent of respondents in France said the country was going in the wrong direction. This contrasts with 40 percent in the UK, 53 percent in western Germany, and 71 percent in Italy.

Given France’s poor economic performance, especially in the old industrial areas, it is hardly surprising there has been a rise in right-wing populism there. Marine Le Pen came in second place in the polls leading into the first ballot on Sunday, April 23, 2017, just as her father did fifteen years earlier before losing in a landslide to Jacques Chirac. She developed a nationalist and protectionist program and pledged to leave the euro area and NATO. Le Pen had plans to lower the retirement age to 60, boost public services, raise welfare payments, and tax firms that hire foreigners.

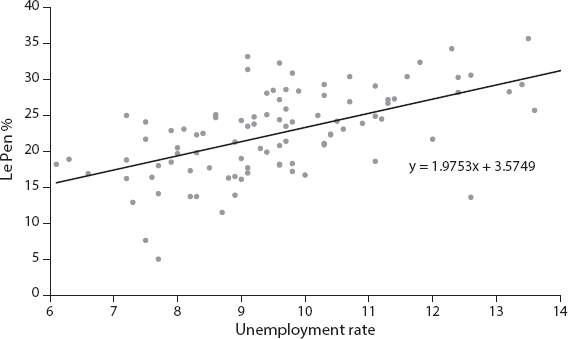

I plot the Le Pen vote by department, similar to counties, against the unemployment rate in figure 10.4. It is clear from the trend lines that the first round of the Le Pen vote is positively correlated with the unemployment rate. I also find the Le Pen vote is negatively correlated with median income and positively correlated with the percentage of high school dropouts and the poverty rate. The Le Pen vote in the second round was also positively correlated with the unemployment rate. This pattern repeats those observed earlier for Brexit and Trump. It’s the same people.

Figure 10.4. Le Pen first-round vote and the unemployment rate. Note: I am grateful to Leigh Thomas and Reuters for providing me with his data from the first round of voting.

As in the UK with Brexit and the United States with Trump, there was a major divide between the big cities and more rural areas, which have higher unemployment rates, higher levels of poverty, and poor provision of public services. In Paris, Bordeaux, Nantes, Rennes, and Lyon, Macron received more than 30 percent of the vote. In Hauts-de-France, which has a 12.1 percent unemployment rate, Le Pen received 31 percent of the vote. In Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (11.4 percent unemployment rate), Le Pen received 28 percent of the vote.24

In the Pas-de-Calais, which has an unemployment rate of 13.3 percent, and which was long dependent on mining, primarily the coal mines near the town of Lens, Le Pen won 34 percent of the vote. Between 1975 and 1984, the region lost over 130,000 jobs and unemployment rose to 14 percent of the working population, well above the national average. In more recent years, the area has faced economic hardship as the mines closed, alongside a decline in the steel industry and major problems in the textile industry. The Front National won large parts of the deindustrialized north and east, as well as the south, while Macron took the west. He was strong in cosmopolitan cities, while Le Pen was strong in small towns and rural areas that felt abandoned. Le Pen took nine of the ten départements with France’s highest unemployment rates.

What happened in France looks much like what happened in the UK and the United States. Less-educated whites living outside the big cities, who had been hurt by economic decline, falling real wages, unemployment, underemployment, and a lack of good jobs, voted for populism. Once again, they were against immigration, from outside the big cities, which have prospered, and the rule of the elites. This time right-wing populism lost. There isn’t going to be a Frexit, but election winner Sebastian Kurz is president of Austria, and his party is in coalition with the far-right Freedom Party (FPO), suggesting that the French election may not be a turning point. This doesn’t seem to be over yet.

Those who were left behind, who were not doing so well, turned toward populism around the world, which gave them hope. They had nowhere else to turn. The elites had left them behind. The commonality of those who voted for change was that they and their communities were not doing well.

And Then QuItaly, Maybe

The Brits narrowly and unexpectedly voted for Brexit, 52–48 percent. Americans elected Trump because of the vagaries of the electoral college, even though he obtained 3 million fewer votes than Hillary Clinton. Macron won in France, but Le Pen made a strong showing and reached the final round, which meant no Frexit. The majority of Brits polled now say they want to nationalize some of the “commanding heights” of the economy—water, electricity, and railways. The UK government recently had to nationalize the East Coast Railway, which had gone bankrupt.25 It doesn’t help that the UK has nine of the ten poorest regions in Europe.26 Inner London is the richest region in Europe.

But this may not be the end of the rise of populism in Europe, as there have been populist uprisings in Italy, Slovenia, Hungary, and Austria. The pandemic isn’t over. In May 2018 Italy struggled to form a government and was faced with a short-lived crisis that sent bond yields spiraling upward. On May 28, 2018, Italian president Sergio Mattarella blocked a bid by two populist parties, which are riding high in the opinion polls, the anti-establishment Five Star and the far-right anti-immigrant Northern League alliance, to form a government. While both are called “populist,” they have conflicting policies, so it isn’t surprising that their efforts to form a government ultimately failed. The Five Star Movement called for a universal basic income of $920 a month, implying a huge increase in government outlays. The Northern League has called for a flat tax rate of 15 percent and actions against refugees. It would also like to see heavy spending on infrastructure.

Both parties wish to roll back pension reforms and other plans aimed at boosting competitiveness. Both are strongly Eurosceptic and show little inclination to be bound by European Union rules and regulations. Both call for scrapping sanctions against Russia. There is likely to be a new set of elections where the main topic will probably be continued membership in the Euro. However, a recent Ipsos poll suggested only 29 percent of Italians supported quitting the Euro.27 Italy has one of the lowest approval levels for membership of the single currency, but disapproval may not be the same as quitting. According to data from the October 2017 Eurobarometer, only 45 percent of Italians think the EU is a “good thing” for their country, compared with 64 percent across the Eurozone as a whole. QuItaly, as it is being called, or Itexit, probably won’t happen.

On May 29, 2018, the Financial Times reported that Five Star leader Luigi di Maio called for a mass protest on June 2, a public holiday: “last night was the darkest in the history of Italian democracy.”28 The day before Tony Barber had argued in the same paper that Italy is home to the strongest anti-establishment parties in Europe and suggested that matters a lot as “events in Italy weigh more on the EU’s destiny than events in the UK, which has been a semi-detached member of the bloc for most of the 45 years since its entry in 1973.”29

Italian stock markets were down 2.5 percent on the news on May 28 and 29, 2018; stock and bond markets around the world were down, including in London, Paris, Frankfurt, Madrid, and Hong Kong, as well as on Wall Street. The Italian two-year yield at 2.5 percent was up 1.7 percentage points in a single day on May 29. Italian banks were hardest hit, with the country’s largest financial institution, UniCredit, falling 5.6 percent. But lenders across Europe also sold off: Spain’s Santander was down 5.4 percent; France’s BNP Paribas dropped 4.5 percent; and Germany’s Commerzbank fell 4 percent. The already struggling Deutsche Bank that is shedding jobs was down 4.6 percent. Some of Wall Street’s biggest banks, including JPMorgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, and Morgan Stanley, were down 4 percent or more.

On May 31, 2018, Giuseppe Conte, a professor, was appointed prime minister with Matteo Salvini of the League and di Maio of Five Star as vice premiers. This avoided the possibility of new elections. Italian markets bounced back as investors judged that having a Five Star–League government was better than new elections with a slim majority. Both of the populist groups have said they will not push, for now, for Euro exit. A road sign proclaiming “Basta Euro” that stood outside the League party’s headquarters was painted over at the end of May. As Gideon Rachman noted on June 4, 2018, in the Financial Times, there is likely lots of trouble brewing.

Matteo Salvini, the League’s leader and Italy’s new interior minister, has promised to speed up deportations and detentions of up to 500,000 illegal immigrants—which could cause angst in Berlin, as well as potentially violating EU law. The League also wants a flat tax of 15 per cent on income. Five Star, its coalition partner, has argued for a universal basic income. Those policies together are a recipe for blowing up the EU’s 3 per cent limit on national budget deficits. If the government in Rome ignores the EU’s fiscal rules, the reaction from Brussels and Berlin will be harsh. When Italy then finds itself under pressure from the bond markets, the likes of Mr Varoufakis and Mr Savona will return to the argument that the EU elite is conspiring against the will of the people.30

On June 5, 2018, Bloomberg reported that Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte pledged in his maiden speech that his government would push through measures ranging from a “citizen’s income” for the poor to tax cuts and curbs on immigration, as he called for a stronger, fairer Europe.31 Italian bonds extended their decline during his speech as he gave investors little indication that he would diverge from the Five Star–League program. Two-year securities led losses, with yields climbing by 16 basis points to 0.92 percent. Those on ten-year notes snapped four days of declines, rising 12 basis points to 2.65 percent. The roller coaster continues.

The Italian unemployment rate for May 2018 was 10.7 percent, down from 14.3 percent in November 2014. No wonder Italians are disgruntled.

There continue to be issues with the Italian budget. The new Italian government wants to spend more, including providing a minimum income for the unemployed, along with cutting taxes and scrapping extensions to the retirement age. The EU Commission and the IMF have both warned against Rome’s stimulus plan.32 The economic battle lines are being drawn in Italy as they have been in the UK over Brexit.

Why Right-Wing Populism?

Populism continues on its march through Europe. Hard-liner Janez Jansa has ridden a right-wing populist wave into power in Slovenia.33 Slovenia looks like it is going to line up politically with Hungary, which reelected the right-wing populist Victor Orban as prime minister in April 2010, and Austria, where a far-right party has emerged as a strong political force. The young Sebastian Kurz of the right-leaning Austrian People’s Party led his party to victory at just 31 years old and is Austria’s youngest chancellor ever. Kurz is moving to the right on migration. Asylum seekers caught trying to cross the Mediterranean should be sent back, he says.34

I first met Vernon Bogdanor in early 2017 when we were both guests on Daily Politics, hosted by my old friend Andrew Neil, at the BBC’s studios at Millbank opposite the Houses of Parliament. We started chatting about populism. He is the great expert on this populism stuff and I listened. He was also David Cameron’s tutor at Oxford, who he said was one of his ablest students. A few days later he kindly sent me a few short essays that he called “squibs.” I was especially taken by his definition of populism. Some say that a populist is merely a politician who proves unexpectedly popular. But perhaps we can try a more precise definition. The elite belong to the exam-passing classes. Most supporters of populist parties, he suggests, do not. We are both interested in the left-behinds who, he suggests, feel a strong sense of disenfranchisement and powerlessness, believing as they do that the political class makes its decisions without consulting their interests and looks down on them as “unreconstructed bigots.” Fascism, he notes, is just a variant of right-wing populism.

A populist, Bogdanor suggests, is someone who believes that the traditional governing parties of moderate left and moderate right, which claim to oppose each other, in reality form a consensus, since they agree upon basic issues. In Britain, France, and the United States, for example, the main parties agreed on the benefits of immigration and the advantages of globalization. In Britain, the three major parties favored Britain’s continued membership in the European Union. The people did not. In another of the squibs he argued that the real debate is not between left and right but between the people and the political class, the elite, which has its own interests in common, which are not those of the people. There surely is something in that suggestion.

The reason why there is right-wing and not left-wing populism, Bogdanor suggested to me, is that the populist reaction is nationalistic. The left continually underestimates the force of nationalism or patriotism, just as it did in the 1930s. Most working-class constituencies are deeply patriotic and conservative. One of the objections to Corbyn, the Labour Party leader in provincial England, Bogdanor suggested, is that he has been rude about the Queen! The left, he suggests, has been caught by identity politics. It has concentrated on the identity of minorities—whether subnational, ethnic, or sexual—and has neglected the identity of the majority, for example, the white English working class, which it regards as bigoted and racist. This can be compared, Bogdanor suggests, with Gordon Brown’s comment in 2010 to a woman in Rochdale, whom he called a bigot.35 Hence the expression of majority identity becomes politically illegitimate for the left. The left has succeeded in identifying itself with nationalism in Greece and Spain, which accounts, Bogdanor suggested, for its success there. There is a deep frustration with the left’s obsession with political correctness and, more generally, with things that people don’t see as relating to them.

In further communication with me Bogdanor suggested that contrary to what the Marxists believed, during a recession, class solidarity weakens but national solidarity increases. Whatever the economic benefits of immigration, it is resented for cultural reasons, as a threat to identity. People said that their communities had been altered out of all recognition and that they had not been consulted about it.

Half a decade ago, Bogdanor suggests, the ambitious would remain in their provincial towns to sustain the economy and take leadership positions. Now they go to elite universities and then work in big cities, leaving whole areas hollowed out. The Great Recession showed that they had made very unwise investments, that they were short-sighted, and that they were often unethical. Their high salaries were held to be a reward for risk-taking. But, when their risks went wrong, they were bailed out by the state. Private-sector gains and public-sector losses. They were incentive-driven capitalists when things went well but turned into socialists when things started going badly! Their victims had no such luxury. Bogdanor is right: one rule for the little people, another rule for the powerful—at least that is how the left-behinds feel.

In private communication with me, Matthew Goodwin, a professor of politics at the University of Kent, commented when I asked him why we have seen a burst of right-wing rather than left-wing populism that the issue “relates more to migration/actual demographic shifts and that the left has been outflanked on those issues, often by manipulative national populists. But also increasingly the left is now having its economic message met/diluted by national populists who are gradually becoming more protectionist (witness Le Pen attacking ‘savage globalisation’ or Sweden Democrats proposing labour market stress testing to protect ‘native’ workers).” Katsambekis (2017) suggests that populist radical-right parties all seem to favor a “strictly ethnic (even racial) understanding of the people, portrayed as a homogeneous organic community, opposing minorities (religious, ethnic, etc.) and expressing xenophobic, racist, or homophobic views. In this sense, such parties tend to be exclusionary and regressive, connecting the well-being of the ‘native’ people to the exclusion of alien ‘others’ and the restriction of the latter’s rights and freedoms.”

Judis (2016) argues that the populists roil the waters. They signal, he suggests, that the prevailing political ideology isn’t working and needs repair and the standard worldview is breaking down. Judis further argues that if Trump were to demand an increase in guards along the Mexican border, that would not open up a gulf between the people and the elite. But promising a wall that the Mexican government will pay for—or the total cessation of immigration—does establish a frontier. Right-wing populists, he suggests, champion the people against an elite that they accuse of coddling a third group, which can consist of immigrants, Islamists, or African American militants. Trump voters, Judis says, invariably praised his self-financing, which was seen as making him independent of lobbyists, which was an important part of his appeal. Rich was OK.

Eatwell and Goodwin have explained the allure of populism succinctly: “Those with fewer qualifications and more traditionalist values are more alarmed about how their societies are changing: they fear the eventual destruction of their community and identity, they believe that both they and their group are losing out, and distrust their increasingly distant representatives. National populists spoke to these voters, albeit in ways that many dislike. For the first time in years their supporters now feel they have an agency in the debate” (2018, 275).

It’s the Elites, Mate

Müller argues persuasively that a necessary but not sufficient condition of populism is to be critical of elites. In addition, he suggests, populists are always anti-pluralist, claiming they and they alone represent the people. Populist protest parties, he argues, cancel themselves out once they win an election as they can’t protest against themselves in government but they can govern as populists, which he suggests goes against the conventional wisdom. Müller explains that any failures of populist movements can still be blamed on elites acting behind the scenes. Populism distorts the democratic process (2016, 4), but he suggests it may be useful in making clear that parts of the population really are unrepresented.

Tom Nichols, who used to work in the Government Department at Dartmouth, writes that the United States is now a country obsessed by the worship of its own ignorance (2017, ix). Trump, he says, won because “he connected with a particular kind of voter who believes that knowing about things like America’s nuclear deterrent is just so much pointy-headed claptrap. Worse, voters not only didn’t care that Trump is ignorant or wrong, they likely were unable to recognize his ignorance or errors” (2017, 212). Americans, he argues, “have reached a point where ignorance, especially of anything related to public policy, is an actual virtue” (2017, x). Trump, Nichols argues, sought power during the 2016 election “by mobilizing the angriest and most ignorant in the electorate” (2017, 215). Oh dear.

These were battles against the establishment. As left-wing columnist and author Owen Jones noted, “The illusion of every era is that it is permanent. Opponents who seem laughably irrelevant and fragmented can enjoy sudden reversals of fortunes. The fashionable common sense of today can become the discredited nonsense of yesterday and with surprising speed” (2014, 314).

The concern may not be about what Trump achieves; it seems that sticking it to the opposition is really what it is about. Charlie Sykes, a former talk-show host in Wisconsin, has argued that much of the conservative news media is now less pro-Trump than it is anti-anti-Trump. The distinction, Sykes argues, is important, “because anti-anti-Trumpism has become the new safe space for the right. Here is how it works,” he suggests. “Rather than defend President Trump’s specific actions, his conservative champions change the subject to (1) the biased ‘fake news’ media, (2) over-the-top liberals, (3) hypocrites on the left, (4) anyone else victimizing Mr. Trump or his supporters, and (5) whataboutism, as in ‘What about Obama?’ and ‘What about Clinton?’”36

This all reminds me of the famous 1973 column by humorist Art Buchwald in relation to Watergate. It contained thirty-six responses for loyal Nixonites who were under attack that he argued they should cut out and carry in their pockets.37 It starts out as follows.

1. Everyone does it.

2. What about Chappaquiddick?

3. A President can’t keep track of everything his staff does.

4. The press is blowing the whole thing up.

5. Whatever Nixon did was for national security.

6. The Democrats are sore because they lost the election.

7. Are you going to believe a rat like John Dean or the president of the United States?

8. Wait till all the facts come out.

9. What about Chappaquiddick?

10. If you impeach Nixon you get Agnew (you didn’t).

19. What about Chappaquiddick?

32. What about Chappaquiddick?

Press coverage of Trump has been unremittingly negative. In a study that obtained much attention in the right-wing press, Trump’s coverage during his first 100 days set a new standard for negativity.38 Of news reports with a clear tone, negative reports outpaced positive ones by 80 percent to 20 percent. Patterson concludes that “the fact that Trump has received more negative coverage than his predecessor is hardly surprising. The early days of his presidency have been marked by far more missteps and miss-hits, often self-inflicted, than any presidency in memory, perhaps ever…. Never in the nation’s history has the country had a president with so little fidelity to the facts, so little appreciation for the dignity of the presidential office, and so little understanding of the underpinnings of democracy” (2016, 15).

Coal and Talc Jobs Are Not Coming Back, and Neither Are Dilapidated British Seaside Towns; Coal Remains Inaccessible because of Underground Flooding

It is hard to see what can be done to bring back jobs to rust-belt states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Ohio as Trump promised. Raising the world price of steel, coal, or talc is a non-starter. Even if there is a giant fiscal stimulus, why would firms not move production to, say, South Carolina, which has a private-sector unionization rate of 1.1 percent or Georgia at 2.7 percent or Texas at 2.5 percent when private-sector unionization rates in the rust belt are much higher (e.g., Michigan, 11.1%)? Technological change may still mean that capital is cheaper than labor, so it’s more machines and robots rather than lots of new jobs for the unskilled. A rising tide can lift all boats of course.

In 1914, 181,000 miners were employed in the anthracite mines of northeastern Pennsylvania. On January 22, 1959, the Knox Coal Company’s mine in Luzerne County, under the Susquehanna River, in the vicinity of Port Griffith, a small town, midway between Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, collapsed and the mighty Susquehanna River poured into the mines, flooding them throughout the interconnected underground system. Shortly after the flooding of the Knox Mine, two of the area’s largest coal companies announced a full withdrawal from the anthracite business. Other companies whose mines lay some distance from the Knox disaster continued to operate on a much smaller scale into the early 1970s. The only anthracite production that still occurs in the area is large-scale surface mining of shallow old works.

Luzerne County’s website suggests that even though the anthracite resource remaining in the ground is substantial, the complex geologic structure, steep terrain, and inefficient early mining of the thicker and more accessible blocks of coal “now preclude the use of modern mechanized equipment underground.” In addition, “Billions of tons of anthracite are still in the ground but remain inaccessible because of underground flooding.”39 Longazel (2016) notes that in the years before 1980 there were consistently more than forty thousand manufacturing jobs in Luzerne County. By 1990 the number had dropped to about twenty-five thousand and by 2016 the number was fewer than twenty thousand.

U.S. coal production is in precipitous decline. In 2015, U.S. coal production, consumption, and employment fell by more than 10 percent. Between 2014 and 2015 the number of mines in Kentucky fell from 252 to 210 and the number of employees fell 13.8 percent. In West Virginia, the number of mines was down from 191 to 151 while the number of employees was down 14 percent. Pennsylvania saw mine numbers dropping from 222 to 195 with employee numbers down 14 percent. Virginia mine numbers dropped from 69 to 65 with employee numbers down 12 percent. According to the BLS, in June 1985, 178,000 people were employed in coal mining. This number was 50,000 in January 2017. By contrast, renewable energy—including wind, solar, and biofuels—now accounts for more than 650,000 U.S. jobs.40 According to the Employment Situation Report published by the BLS in February 2019, the number of coal-mining jobs in January 2019 was up 1,800 to 52,700 from 50,900 a year earlier.

Donald Trump held a rally in Luzerne County to raise local hopes that things might change. He told a crowd at Wilkes-Barre, the seat of Luzerne County, on October 10, 2016, “Oh, we’re going to make Pennsylvania so rich again, your jobs are coming back. We’re going to be ending illegal immigration. We’re going to stop the jobs from pouring out of our country.41

Justin Emershaw voted for Trump. After hearing Clinton’s negative remarks during the campaign about coal, he said Trump struck a nerve with the coal industry when he talked about reopening mines. “The industry is really hurting,” said Emershaw, who works for Coal Contractors Inc. in Hazleton, in Luzerne County. “We need somebody who’s really going to make a change with it.”42 However, David Victor, an energy expert at the University of California–San Diego, observed a few days after the election, “I suspect there is no fuel for which the Trump victory will be more irrelevant than for coal.”43 The town of Hazleton saw the size of its Latino population rise from 4 percent in 2000 to 38 percent in 2006. In 2006, it passed an ordinance called the Illegal Immigration Relief Act (IIRF) that made it illegal for landlords to rent to undocumented immigrants and threatened fines for employers who hired them (Longazel 2016).44 The ordinance was challenged in court and was declared illegal.

In 2016, 5,644 Democrats in Luzerne County changed their registration to Republican. Luzerne County flipped from voting for Obama by 5 points in 2012 to voting for Trump by 20 points.

There were unsuccessful interventions in other sectors too. Donald Trump offered $800 million in tax breaks to stop a Carrier Corporation furnace factory in Indiana from closing, keeping 800 production jobs from going to Mexico. Despite that the company still plans to shift 1,300 jobs to Mexico. He also warned another Indiana company, Rexnord, about its plans to move its factory south of the border.45 On December 2, 2016, Trump tweeted, “Rexnord of Indiana is moving to Mexico and rather viciously firing all of its 300 workers. This is happening all over our country. No more!”

Two months later Rexnord was still planning on moving to Mexico. Andrew Tangel reports that workers have been packing up machines while their replacements, visiting from Mexico, learn to do their jobs. Machinist Tim Mathis, who had worked at Rexnord for twelve years, said, “That’s a real kick in the ass to be asked to train your replacement. To train the man that’s going to eat your bread.” Gary Canter, a machinist at Rexnord for eight years, said, “It just puzzles me to think that they have to [reduce costs] by dumping us out. It’s very un-American.” Tangel reported that Canter had voted for Trump and remained hopeful the president would ultimately boost manufacturing, creating new jobs for his colleagues elsewhere even if the Rexnord plant isn’t spared. “We gave this man a chance because it wasn’t a typical politician that’s done nothing for us.”46

The false claims go on. President Trump had made claims at a Pennsylvania rally in August 2018 that “U.S. Steel is opening up seven plants.” Fox News reported that “the Pittsburgh-based company has made no such announcement.”47 Steel jobs are not coming back.

Obama won Trumbull County, Ohio, by 23 points but Trump won it by 6, not least on the promise of bringing manufacturing jobs back to Ohio. On November 26, 2018, General Motors announced that it would be closing five plants in the United States and cutting around fourteen thousand jobs. One of the plants is the Lordstown plant in Trumbull County, which had been there for fifty years; others are to be closed in Maryland and Michigan. Part of the problem was that the facility produced the Chevy Cruze, a more fuel-efficient vehicle, but sales fell because of lower fuel prices. General Motors also cited Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminum as raising costs. In June GM lowered its profit outlook for the year because it said tariffs were driving up production costs, raising prices even on domestic steel. Rising interest rates were also raising costs. The move follows job reductions by Ford.48 Car jobs are not coming back.

Coal has almost entirely died in the UK. Most of the old coal-mining towns voted for Brexit. Coal production in the UK in the 1960s was around 177 million tonnes and the industry employed half a million miners. Output fell to 114 million tonnes by the mid-1970s and 300,000 workers. The National Union of Miners (NUM) had a bitter fight with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, which resulted in a yearlong national strike in 1984–85, by which time output was at 133 million tonnes and 180,000 workers. Pit closures continued through the 1990s with only 21 million tonnes mined with 13,000 workers.

From 2000 to 2010 the coal industry contracted further, with output falling to 10 million tonnes. Kellingly, the UK’s last deep mine, was closed in 2015. In 1982, the NUM had 170,000 members. By 2015 the number of members had fallen to 100.49 In 1984 Yorkshire had 56 collieries. Today there are none. The coal mines in Yorkshire were concentrated in a few towns. For example, Barnsley had eleven pits in 1984; Doncaster had nine; Rotherham had ten; and Wakefield had fifteen. Each of these towns voted Brexit by large majorities—Barnsley (68%), Doncaster (69%), Rotherham (68%), and Wakefield (66%) against 52 percent nationally.

The problem with coal that is distinctive is that it is geographically concentrated. When coal jobs go, house prices plummet, and people can’t just move out because they can’t sell. Wales voting for Brexit is an obvious example. The same isn’t true for taxi drivers, who will potentially be replaced by driverless cars as the concentration of economic activity in small towns isn’t the same. They are not all located in a narrow Welsh valley like the Rhondda.

Wakefield, once a major coal town where 10,000 Poles live, is home to various Polish beauty parlors and hairdressers, estate agents, off licenses, dentists and doctors, and a string of Polish delis. Aneta Duchniak, who two years earlier opened the first Polish restaurant in Wakefield, wondered after Brexit if she would have many British customers: “They said, ‘We want to support you, it’s nothing against you, it’s against Brussels controlling us.’ Lots of my regulars voted to leave. One of them even told me she has a Polish cleaner. Roger, who comes in all the time for a cup of tea, voted out and he says he worked with lots of Polish people when he was a miner.”50 I recall watching an edition of BBC’s Question Time from Wakefield where it was clear that there was a great deal of resentment in the air. Members of the audience objected to being thought of as “stupid,” and one woman complained that “people are making out as if we are uneducated, that we didn’t know what we were doing and they need to stop doing that.” Another said, “I feel like we were treated by certain people, as this lady said, that we’re uneducated stupid northerners, we’re all racist up here, and we don’t know what we’re doing.”51

St. Lawrence County, New York, on the U.S.-Canadian border, is the birthplace of my boss, Dartmouth president Phil Hanlon, who explained to me that talc mining was extremely important there when he was growing up. Apparently, the quality was high, but advances in technology meant that the quality of lower-grade talc found abroad could be improved and was a lot cheaper, with bad effect. Lower world prices wiped out the talc industry in St. Lawrence and the last mine closed in 2008. It hasn’t helped that there have been concerns about the health risks of talc with courts awarding several multimillion-dollar payouts.52 These lawsuits relate not just to its harmful impacts on users (causing ovarian cancer) but also to the miners who caught mesothelioma from breathing in the dust. In 2018 Johnson & Johnson and a company that supplied it with talc from mines in Vermont were ordered to pay a combined $117 million in damages after a jury found their popular baby powder product contained asbestos that caused cancer.53

The U.S. Geological Survey reported that talc production in millions of metric tons was 1,270 in 1990; 511 in 2009; and 550 in 2017.54 In 2012 St. Lawrence County voted 57 percent Obama and 41 percent Romney. In 2016 St. Lawrence voted 51 percent Trump and 42 percent Clinton. Hope springs eternal, but talc mining sure as heck is not coming back.

After Arizona passed a series of tough anti-immigration laws, Bob Davis in the Wall Street Journal reported that Rob Knorr couldn’t find enough Mexican field hands to pick his jalapeño peppers. He sharply reduced his acreage and invested $2 million developing a machine to remove pepper stems. His goal was to cut the number of laborers he needed by 90 percent and to hire higher-paid U.S. machinists instead. Mr. Knorr, Davis reports, said he was willing to pay $20 an hour to operators of harvesters and other machines, compared with about $13 an hour for field hands. He says he can hire skilled machinists at community colleges, so he can rely less on migrant labor. “I can find skilled labor in the U.S.,” he says. “I don’t have to go to bed and worry about whether harvesting crews will show up.”55 Technology remains an issue.

What about Chappaquiddick?

The concern especially in the United States and the UK is that nothing much is going to change and there will be widespread disappointment. Rioting in Paris may yet spread. The question, then, is who will be blamed. The media, the Democrats, the deep state, weak establishment Republicans, and Never-Trumpers are all on the menu. Already the guns are out for the Mueller investigation. More bloody excuses. The possibility, though, has arisen from the meeting of the G7 in Quebec, Canada, that Make America Great Again (MAGA) may end up being America Alone.56 Trump’s proposal to bring Russia back to the G7 didn’t go down well. India, a nuclear power, has an economy 50 percent larger than Russia’s, and what about China? There has been no pull-back from Crimea, which is why Russia was kicked out of the G7 in the first place. Trump eventually refused to sign the joint communiqué.

The summits with NATO and G7 were nothing short of disastrous. Nothing of substance came out of the meeting with Kim Jong-un in Singapore or with Putin in Helsinki. Trump is fully embroiled in a number of legal issues including the Mueller probe into Russian collusion. There have been multiple indictments including several from Trump’s campaign. There are also a number of lawsuits involving the emoluments clause in the Constitution in relation to the Trump Hotel in Washington, D.C., as well as lawsuits relating to payoffs to two women with whom Trump allegedly had extra-marital affairs. Plus, his fixer, Michael Cohen, and others are cooperating with special prosecutor Robert Mueller. Trump isn’t going to have much time to spend fixing the plight of his core voters now that the Democrats have taken control of the House (as of January 2019) and subpoenas may start to fly.

The pain and suffering that I have documented have come about as communities have fractured and decent-paying jobs for the less educated have disappeared across advanced countries. Right-wing populist politicians told the left-behinds that they would do lots of deals and all would be well. They are not cracking on with Brexit, coal and steel jobs are not showing up, and tourists are not rushing back to English seaside towns. Tax cuts for the rich and a few dregs for the poor and there lurks the possibility of cuts to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Maybe a big infrastructure bill will do the trick? Time will tell, but sadly, nobody had a plan and they still don’t. Delivering is harder than making promises.

What about Chappaquiddick?